Mount Everestn Sherry Ortner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alicia Jewett Master's Thesis

“Before the practice, mountains are mountains, during the practice, mountains are not mountains, and after the realization, mountains are mountains” – Zen Master Seigen University of Alberta Metaphor and Ecocriticism in Jon Krakauer’s Mountaineering Texts by Alicia Aulda Jewett A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Comparative Literature Office of Interdisciplinary Studies ©Alicia Aulda Jewett Fall 2012 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Abstract This study examines Jon Krakauer’s three mountaineering texts, Eiger Dreams, Into the Wild, and Into Thin Air, from an ecocritical perspective for the purpose of implicating literature as a catalyst of change for the current environmental crisis. Language, as a means of understanding reality, is responsible for creating and reinforcing ethical ways of understanding our relationship with nature. Krakauer’s texts demonstrate the dangers of using metaphor to conceive nature by reconstructing the events of Chris McCandless’ journey to Alaska, his own experience climbing The Devil’s Thumb, and the 1996 disaster that occurred during his summit of Mount Everest. -

Catalogue 48: June 2013

Top of the World Books Catalogue 48: June 2013 Mountaineering Fiction. The story of the struggles of a Swiss guide in the French Alps. Neate X134. Pete Schoening Collection – Part 1 Habeler, Peter. The Lonely Victory: Mount Everest ‘78. 1979 Simon & We are most pleased to offer a number of items from the collection of American Schuster, NY, 1st, 8vo, pp.224, 23 color & 50 bw photos, map, white/blue mountaineer Pete Schoening (1927-2004). Pete is best remembered in boards; bookplate Ex Libris Pete Schoening & his name in pencil, dj w/ edge mountaineering circles for performing ‘The Belay’ during the dramatic descent wear, vg-, cloth vg+. #9709, $25.- of K2 by the Third American Karakoram Expedition in 1953. Pete’s heroics The first oxygenless ascent of Everest in 1978 with Messner. This is the US saved six men. However, Pete had many other mountain adventures, before and edition of ‘Everest: Impossible Victory’. Neate H01, SB H01, Yak H06. after K2, including: numerous climbs with Fred Beckey (1948-49), Mount Herrligkoffer, Karl. Nanga Parbat: The Killer Mountain. 1954 Knopf, NY, Saugstad (1st ascent, 1951), Mount Augusta (1st ascent) and King Peak (2nd & 1st, 8vo, pp.xx, 263, viii, 56 bw photos, 6 maps, appendices, blue cloth; book- 3rd ascents, 1952), Gasherburm I/Hidden Peak (1st ascent, 1958), McKinley plate Ex Libris Pete Schoening, dj spine faded, edge wear, vg, cloth bookplate, (1960), Mount Vinson (1st ascent, 1966), Pamirs (1974), Aconcagua (1995), vg. #9744, $35.- Kilimanjaro (1995), Everest (1996), not to mention countless climbs in the Summarizes the early attempts on Nanga Parbat from Mummery in 1895 and Pacific Northwest. -

Route Was Then Soloed on the Right Side Ofthe W Face Ofbatian (V + ,A·L) by Drlik, Which Is Now Established As the Classic Hard Line on the Mountain

route was then soloed on the right side ofthe W face ofBatian (V + ,A·l) by Drlik, which is now established as the classic hard line on the mountain. On the Buttress Original Route, Americans GeoffTobin and Bob Shapiro made a completely free ascent, eliminating the tension traverse; they assessed the climb as 5.10 + . Elsewhere, at Embaribal attention has concentrated on the Rift Valley crag-further details are given in Mountain 73 17. Montagnes 21 82 has an article by Christian Recking on the Hoggar which gives brief descriptions of 7 of the massifs and other more general information on access ete. The following guide book is noted: Atlas Mountains Morocco R. G. Collomb (West Col Productions, 1980, pp13l, photos and maps, £6.00) ASIA PAMIRS Russian, Polish, Yugoslav and Czechoslovak parties were responsible for a variety ofnew routes in 1979. A Polish expedition led by Janusz Maczka established a new extremely hard route on the E face of Liap Nazar (5974m), up a prominent rock pillar dubbed 'one of the mOSt serious rock problems of the Pamir'. It involved 70 pitches, 40 ofthem V and VI, all free climbed in 5 days, the summit being reached on 6 August. The party's activities were halted at one point by stone avalanches. On the 3000m SW face ofPeak Revolution (6974m) 2 teams, one Russian and one Czech/Russian, climbed different routes in July 1979. KARAKORAM Beginning in late March 1980, Galen Rowell, leader, Dan Asay, Ned Gillette and Kim Schmitz made a 435km ski traverse of the Karakoram in 42 days, setting off carrying 50kg packs. -

Human Factors in High-Altitude Mountaineering

Journal of Human Performance in Extreme Environments Volume 12 Issue 1 Article 1 Published online: 5-8-2015 Human Factors in High-Altitude Mountaineering Christopher D. Wickens Alion Science and Technology, [email protected] John W. Keller Alion Science and Technology, [email protected] Christopher Shaw Alion Science and Technology, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/jhpee Part of the Industrial and Organizational Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Wickens, Christopher D.; Keller, John W.; and Shaw, Christopher (2015) "Human Factors in High-Altitude Mountaineering," Journal of Human Performance in Extreme Environments: Vol. 12 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. DOI: 10.7771/2327-2937.1065 Available at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/jhpee/vol12/iss1/1 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. This is an Open Access journal. This means that it uses a funding model that does not charge readers or their institutions for access. Readers may freely read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full texts of articles. This journal is covered under the CC BY-NC-ND license. Human Factors in High-Altitude Mountaineering Christopher D. Wickens, John W. Keller, and Christopher Shaw Alion Science and Technology Abstract We describe the human performance and cognitive challenges of high altitude mountaineering. The physical (environmental) and internal (health) stresses are first described, followed by the motivational factors that lead people to climb. The statistics of mountaineering accidents in the Himalayas and Alaska are then described. -

High-Elevation Limits and the Ecology of High-Elevation Vascular Plants: Legacies from Alexander Von Humboldt1

a Frontiers of Biogeography 2021, 13.3, e53226 Frontiers of Biogeography REVIEW the scientific journal of the International Biogeography Society High-elevation limits and the ecology of high-elevation vascular plants: legacies from Alexander von Humboldt1 H. John B. Birks1,2* 1 Department of Biological Sciences and Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research, University of Bergen, PO Box 7803, Bergen, Norway; 2 Ecological Change Research Centre, University College London, Gower Street, London, WC1 6BT, UK. *Correspondence: H.J.B. Birks, [email protected] 1 This paper is part of an Elevational Gradients and Mountain Biodiversity Special Issue Abstract Highlights Alexander von Humboldt and Aimé Bonpland in their • The known uppermost elevation limits of vascular ‘Essay on the Geography of Plants’ discuss what was plants in 22 regions from northernmost Greenland known in 1807 about the elevational limits of vascular to Antarctica through the European Alps, North plants in the Andes, North America, and the European American Rockies, Andes, East and southern Africa, Alps and suggest what factors might influence these upper and South Island, New Zealand are collated to provide elevational limits. Here, in light of current knowledge a global view of high-elevation limits. and techniques, I consider which species are thought to be the highest vascular plants in twenty mountain • The relationships between potential climatic treeline, areas and two polar regions on Earth. I review how one upper limit of closed vegetation in tropical (Andes, can try to -

Mount Everest, the Reconnaissance, It Was, Claimed Eric Shipton

The Forgotten Adventure: Mount Everest, The Reconnaissance, 1935. T o n y A s t i l l . F o r e w o r d b y L o r d H u n t . I ntroduction b y S i r E d m u n d H i l l a r y . S outhhampton : L e s A l p e s L i v r e , 2005. 359 PAGES, NUMEROUS BLACK & WHITE PHOTOGRAPHS, AND 2 FOLDING MAPS PLUS A UNIQUE DOUBLE DUST-JACKET OF A 1 9 3 5 c o l o r topographic c o u n t o u r m a p o f Mt. E v e r e s t ’ s n o r t h f a c e i n T i b e t b y M i c h a e l S p e n d e r . £ 3 0 . It was, claimed Eric Shipton famously, “a veritable orgy of moun tain climbing.” In May 1935, Britain’s best mountaineers, including Shipton, longtime climbing partner Bill Tilman, plus 15 Sherpas, among them a 19-year-old novice, Tenzing Norgay, embarked from Darjeeling on the fourth-ever Mt. Everest expedition. In large part because no expedition book was later penned by Shipton, their 27-year-old leader, the 1935 Everest Reconnaissance Expedi tion has remained largely unknown and unlauded. No more! Seven decades later, The Forgotten Adventure reveals the never-before-told climbing adventures of three of the twentieth-century mountaineerings most revered icons reveling in the Himalayan glory of their youth. -

1953 Conquest of Mount Everest

1953 Conquest of Mount Everest Mount Everest is in the Himalaya mountain range located between Nepal and Tibet, an autonomous region of China. At 8,849 meters (29,032 feet), it is considered the tallest point on Earth. In the 19th century, the mountain was named after George Everest, a former Surveyor General of India. The Tibetan name is Chomolungma, which means “Mother Goddess of the World.” The Nepali name is Sagarmatha. The 1953 British Mount Everest expedition was the ninth to attempt the first ascent and the first confirmed to have succeeded when Sherpa Tenzing Norgay and (later Sir) Edmund Hillary reached the summit on 29 May 1953. Led by Colonel John Hunt, it was organised and financed by the Joint Himalayan Committee. News of the expedition's success reached London in time to be released on the morning of Queen Elizabeth II's coronation on 2nd June. The conquest of Everest caught the imagination of the world. So, there are many commemorative & souvenir issues & first day covers. Consequently, it can make a good philatelic theme. This display shows just a small selection of what is available. This Indian first day cover shows a photo, taken by Edmund Hillary, of Sherpa Tenzing Norgay on the summit. Postcard - Edmund Hillary, Tenzing Norgay & Sir John Hunt’s Expedition Team Sir John Hunt (L), leader of the British Everest expedition, and Sir Edmund Hillary (R) arrive at Lancaster House for reception being given in their honour. Earlier they had been received by Queen Elizabeth who knighted the two men. Edmund Hilary Quotes “People do not decide to become extraordinary. -

Everest 1962 I Maurice Isserman

WIRED MAD, ILL-EQUIPPED AND ADMIRABLE: EVEREST 1962 I MAURICE ISSERMAN ust over a half century Jago, on May 8, 1962, four climbers stood atop a Himalayan icefall, watching the last of their Sherpa porters vanish amid the bright, thin air. For the next month, Woodrow Wilson Sayre, Norman Hansen, Roger Hart and Hans-Peter Duttle would be on their own. 88 T!" #$%%$&'() *$+('(), they’d set o, from a high camp to attempt the -rst ascent of Gyachung Kang, a mountain on the Nepalese- Tibetan border—or so Sayre had told the Nep- alese o.cials back in Kathmandu who granted him the permit. Had his American-Swiss party reached the summit of their announced objec- tive, it would have been an impressive coup, considering that none of them had climbed in the Himalaya before, and only two had ever reached an elevation of more than 20,000 feet. At 26,089 feet (7952m), Gyachung Kang fell just below the arbitrary 8000-meter altitude distinguishing other peaks as the pinnacle of mountaineering ambitions. But Gyachung Kang wouldn’t be climbed [Facing Page] Map of the 1962 team’s approach to Mt. Everest (8848m). Jeremy Collins l [This Page] Woodrow “Woody” Wilson until 1964. /e 1962 expedition had another Sayre on the Nup La. “We made three basic decisions in planning for Everest. We were going without permission, we were objective in mind, located about -fteen miles going without Sherpas, and we were going without oxygen,” Sayre wrote in Four Against Everest. Hans-Peter Duttle collection farther east as the gorak (the Himalayan crow) 0ies. -

The Modernisation of Elite British Mountaineering

The Modernisation of Elite British Mountaineering: Entrepreneurship, Commercialisation and the Career Climber, 1953-2000 Thomas P. Barcham Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of De Montfort University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Submission date: March 2018 Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................................... 4 Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................................... 5 Table of Abbreviations and Acronyms .................................................................................................... 6 Table of Figures ....................................................................................................................................... 7 Chapter 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 8 Literature Review ............................................................................................................................ 14 Definitions, Methodology and Structure ........................................................................................ 29 Chapter 2. 1953 to 1969 - Breaking a New Trail: The Early Search for Earnings in a Fast Changing Pursuit .................................................................................................................................................. -

Original Photographs from the Legendary First Ascent PDF Book Jul 25, Randall Rated It Really Liked It

THE CONQUEST OF EVEREST: ORIGINAL PHOTOGRAPHS FROM THE LEGENDARY FIRST ASCENT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK George Lowe,Huw Lewis-Jones | 240 pages | 15 May 2013 | Thames & Hudson Ltd | 9780500544235 | English | London, United Kingdom The Conquest of Everest: Original Photographs from the Legendary First Ascent PDF Book Jul 25, Randall rated it really liked it. Continue to browse in english. Alfred Gregory. The expedition's cameraman, Tom Stobart , produced a film called The Conquest of Everest , which appeared later in [53] and was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature. Retrieved 21 June You May Also Like. Michael Ward. The photography is a true step into their world and humbles you to behold it' Photography Monthly 'The photographs are stunning and, in many cases, moving' Financial Times. The following year, Lowe went with them to Nepal as a member of the expedition to Cho Oyu aiming to explore physiology and oxygen flow rates. Illustrations: The mountaineers were accompanied by Jan Morris known at the time under the name of James Morris , the correspondent of The Times newspaper of London, and by porters , so that the expedition in the end amounted to over four hundred men, including twenty Sherpa guides from Tibet and Nepal, with a total weight of ten thousand pounds of baggage. Which being interpreted meant: "Summit of Everest reached on May 29 by Hillary and Tenzing" John Hunt at Base Camp had lost hope that news of the successful ascent would reach London for the Coronation, and they listened with "growing excitement and amazement" when it was announced on All India Radio from London on the evening of 2 June, the day of the Coronation. -

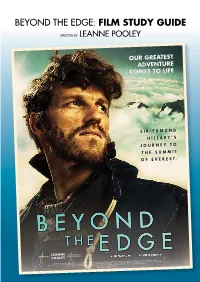

Beyond the Edge: Film Study Guide

BEYOND THE EDGE: FILM STUDY GUIDE DIRECTED BY LEANNE POOLEY “WE KNOCKED THE BASTARD OFF” SIR EDMUND HILLARY OUR GREATEST ADVENTURE COMES TO LIFE SIR EDMUND HILLARY’S JOURNEY TO THE SUMMIT OF EVEREST. LEANNE (THE TOPP TWINS: DIRECTED BY POOLEY UNTOUCHABLE GIRLS) GENERAL FILM CORPORATION IN ASSOCIATION WITH THE NEW ZEALAND FILM COMMISSION NZ ON AIR’s PLATINUM FUND AND DIGIPOST PRESENTS A MATTHEW METCALFE PRODUCTION “BEYOND THE EDGE” HAIR AND MAKE-UP DESIGNER DAVINA LAMONT COSTUME DESIGNER BARBARA DARRAGH SOUND DESIGN BRUNO BARRETT-GARNIER ORIGINAL MUSIC BY DAVID LONG LINE PRODUCER CATHERINE MADIGAN PRODUCTION DESIGNER GRANT MAJOR DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY RICHARD BLUCK EDITOR TIM WOODHOUSE SCREEN STORY BY MATTHEW METCALFE AND LEANNE POOLEY PRODUCED BY MATTHEW METCALFE WRITTEN AND DIRECTED BY LEANNE POOLEY © 2013 GFC (EVEREST) LTD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Check the Classification COMING TO CINEMAS OCTOBER 24 1 BEYOND THE EDGE STARRING Chad Moffitt, Sonam Sherpa IN CINEMAS OCTOBER 24 “It’s not the mountain we conquer – but ourselves.” SIR EDMUND HILLARY 60 years ago on May 29, 1953, two men stood for the first time on the top of the world on the summit of Mount Everest. As news of their achievement filtered out, Queen Elizabeth the II was preparing for her Coronation on June 2 and the world was already in a mood to celebrate. www.beyondtheedgefilm.com CONTACT: Caroline Whiteway RIALTO DISTRIBUTION [email protected] 2 JOURNEY TO THE EDGE FILM STUDY GUIDE BY SUSAN BATTYE The following activities are based on the achievement objectives in the New Zealand English Curriculum and Media and English NCEA Achievement Standards. -

THE RESONANCE of EXPLORATION by Patrick Cassidy

THE RESONANCE OF EXPLORATION by Patrick Cassidy B.A. (The Catholic University of America) 2012 THESIS / CAPSTONE Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in HUMANITIES in the GRADUATE SCHOOL of HOOD COLLEGE April 2019 Accepted: Amy Gottfried, Ph.D. Corey Campion, Ph.D. Committee Member Program Director Tammy Krygier, Ph.D. Committee Member April M. Boulton, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School Corey Campion, Ph.D. Capstone Adviser EMBARKATION What constitutes the crowning achievement for a nation or a society? In his book Men From Earth, Buzz Aldrin stated that the Apollo Program was the single most audacious endeavor in human history.1 Aldrin implied that there is a pinnacle of achievement which a nation reaches. In some cases this pinnacle is represented in a physical structure, but in others it is represented in an extraordinary feat. In his essay, “Apollo’s Stepchildren: New Works on the American Lunar Program,” Matthew Hersch expanded on Aldrin’s point. He stated, “History tends to remember each civilization for a single achievement: the Egyptians, their pyramids; the Chinese, their Great Wall; the Romans, their roads.”2 In addition to these architectural or engineering achievements, an extraordinary feat such as an exploratory endeavor can stand as the crowning achievement for a nation. There are several explorations which come to mind that serve as the crowning achievement for the nations involved. As Aldrin pointed out, the landing of men on the moon in 1969 is perceived as a pinnacle of achievement for Americans. In the same context, the Soviet Space Program and its achievements in the 1960s, represent a crowning achievement for Russia.