Tenzing Norgay's Four Flags

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vividh Bharati Was Started on October 3, 1957 and Since November 1, 1967, Commercials Were Aired on This Channel

22 Mass Communication THE Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, through the mass communication media consisting of radio, television, films, press and print publications, advertising and traditional modes of communication such as dance and drama, plays an effective role in helping people to have access to free flow of information. The Ministry is involved in catering to the entertainment needs of various age groups and focusing attention of the people on issues of national integrity, environmental protection, health care and family welfare, eradication of illiteracy and issues relating to women, children, minority and other disadvantaged sections of the society. The Ministry is divided into four wings i.e., the Information Wing, the Broadcasting Wing, the Films Wing and the Integrated Finance Wing. The Ministry functions through its 21 media units/ attached and subordinate offices, autonomous bodies and PSUs. The Information Wing handles policy matters of the print and press media and publicity requirements of the Government. This Wing also looks after the general administration of the Ministry. The Broadcasting Wing handles matters relating to the electronic media and the regulation of the content of private TV channels as well as the programme matters of All India Radio and Doordarshan and operation of cable television and community radio, etc. Electronic Media Monitoring Centre (EMMC), which is a subordinate office, functions under the administrative control of this Division. The Film Wing handles matters relating to the film sector. It is involved in the production and distribution of documentary films, development and promotional activities relating to the film industry including training, organization of film festivals, import and export regulations, etc. -

An Indian Englishman

AN INDIAN ENGLISHMAN AN INDIAN ENGLISHMAN MEMOIRS OF JACK GIBSON IN INDIA 1937–1969 Edited by Brij Sharma Copyright © 2008 Jack Gibson All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted by any means—whether auditory, graphic, mechanical, or electronic—without written permission of both publisher and author, except in the case of brief excerpts used in critical articles and reviews. Unauthorized reproduction of any part of this work is illegal and is punishable by law. ISBN: 978-1-4357-3461-6 Book available at http://www.lulu.com/content/2872821 CONTENTS Preface vii Introduction 1 To The Doon School 5 Bandarpunch-Gangotri-Badrinath 17 Gulmarg to the Kumbh Mela 39 Kulu and Lahul 49 Kathiawar and the South 65 War in Europe 81 Swat-Chitral-Gilgit 93 Wartime in India 101 Joining the R.I.N.V.R. 113 Afloat and Ashore 121 Kitchener College 133 Back to the Doon School 143 Nineteen-Fortyseven 153 Trekking 163 From School to Services Academy 175 Early Days at Clement Town 187 My Last Year at the J.S.W. 205 Back Again to the Doon School 223 Attempt on ‘Black Peak’ 239 vi An Indian Englishman To Mayo College 251 A Headmaster’s Year 265 Growth of Mayo College 273 The Baspa Valley 289 A Half-Century 299 A Crowded Programme 309 Chini 325 East and West 339 The Year of the Dragon 357 I Buy a Farm-House 367 Uncertainties 377 My Last Year at Mayo College 385 Appendix 409 PREFACE ohn Travers Mends (Jack) Gibson was born on March 3, 1908 and J died on October 23, 1994. -

Tibet Under Chinese Communist Rule

TIBET UNDER CHINESE COMMUNIST RULE A COMPILATION OF REFUGEE STATEMENTS 1958-1975 A SERIES OF “EXPERT ON TIBET” PROGRAMS ON RADIO FREE ASIA TIBETAN SERVICE BY WARREN W. SMITH 1 TIBET UNDER CHINESE COMMUNIST RULE A Compilation of Refugee Statements 1958-1975 Tibet Under Chinese Communist Rule is a collection of twenty-seven Tibetan refugee statements published by the Information and Publicity Office of His Holiness the Dalai Lama in 1976. At that time Tibet was closed to the outside world and Chinese propaganda was mostly unchallenged in portraying Tibet as having abolished the former system of feudal serfdom and having achieved democratic reforms and socialist transformation as well as self-rule within the Tibet Autonomous Region. Tibetans were portrayed as happy with the results of their liberation by the Chinese Communist Party and satisfied with their lives under Chinese rule. The contrary accounts of the few Tibetan refugees who managed to escape at that time were generally dismissed as most likely exaggerated due to an assumed bias and their extreme contrast with the version of reality presented by the Chinese and their Tibetan spokespersons. The publication of these very credible Tibetan refugee statements challenged the Chinese version of reality within Tibet and began the shift in international opinion away from the claims of Chinese propaganda and toward the facts as revealed by Tibetan eyewitnesses. As such, the publication of this collection of refugee accounts was an important event in the history of Tibetan exile politics and the international perception of the Tibet issue. The following is a short synopsis of the accounts. -

Web-Book Catalog 2021-05-10

Lehigh Gap Nature Center Library Book Catalog Title Year Author(s) Publisher Keywords Keywords Catalog No. National Geographic, Washington, 100 best pictures. 2001 National Geogrpahic. Photographs. 779 DC Miller, Jeffrey C., and Daniel H. 100 butterflies and moths : portraits from Belknap Press of Harvard University Butterflies - Costa 2007 Janzen, and Winifred Moths - Costa Rica 595.789097286 th tropical forests of Costa Rica Press, Cambridge, MA rica Hallwachs. Miller, Jeffery C., and Daniel H. 100 caterpillars : portraits from the Belknap Press of Harvard University Caterpillars - Costa 2006 Janzen, and Winifred 595.781 tropical forests of Costa Rica Press, Cambridge, MA Rica Hallwachs 100 plants to feed the bees : provide a 2016 Lee-Mader, Eric, et al. Storey Publishing, North Adams, MA Bees. Pollination 635.9676 healthy habitat to help pollinators thrive Klots, Alexander B., and Elsie 1001 answers to questions about insects 1961 Grosset & Dunlap, New York, NY Insects 595.7 B. Klots Cruickshank, Allan D., and Dodd, Mead, and Company, New 1001 questions answered about birds 1958 Birds 598 Helen Cruickshank York, NY Currie, Philip J. and Eva B. 101 Questions About Dinosaurs 1996 Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, NY Reptiles Dinosaurs 567.91 Koppelhus Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, N. 101 Questions About the Seashore 1997 Barlowe, Sy Seashore 577.51 Y. Gardening to attract 101 ways to help birds 2006 Erickson, Laura. Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA Birds - Conservation. 639.978 birds. Sharpe, Grant, and Wenonah University of Wisconsin Press, 101 wildflowers of Arcadia National Park 1963 581.769909741 Sharpe Madison, WI 1300 real and fanciful animals : from Animals, Mythical in 1998 Merian, Matthaus Dover Publications, Mineola, NY Animals in art 769.432 seventeenth-century engravings. -

The Changing Peasant: Part 2: the Uprooted

19791No. 41 by Richard Critchfield The Changing Peasant Asia [ RC-4-'793 Part II: The Uprooted Theirs is the true lost horizon. Whatever their number, most jutting rocks of shale, schist, and Tibetans are nomadic shepherds limestone. Tibet is the source of all The Tibetan homeland is still so who live in yak-hair tents and move the great rivers of Asia: the Sutlej remote, unmapped, unsurveyed, about much of the year in search of and Indus, the Ganges and and unexplored that in 1979 less is grass for their large herds of yaks, Brahmaputra, the Salween, known about its great Chang Tang sheep, goats, and horses. Aside Yangtze, and Mekong. Violent plateau and Himalayan-high from Lhasa (population 50,000) and gales, dust storms, and icy winds mountain ranges than is known some town-like monasteries, before blow almost every day. about the craters of the moon. the Chinese occupation almost no Until the Chinese occupation the human habitations existed; the Tibet remains a mystery. wheel, considered sacred, was Tibetan herdsman's life, like that of never used: horses, camels, yaks, the Arab Bedouin, revolves around sheep, and men provided the only It is now 29 years since Mao Tse- his livestock, their wool for clothing tung's armies invaded what had transport over rugged tracks and and shelter and their meat and milk precarious bridges spanning deep almost always been an independent for food. sovereign country and declared it an narrow gorges. Even the way of autonomous area within the The Tibetans are racially and death was harsh, the bodies being People's Republic of China. -

Catalogue 48: June 2013

Top of the World Books Catalogue 48: June 2013 Mountaineering Fiction. The story of the struggles of a Swiss guide in the French Alps. Neate X134. Pete Schoening Collection – Part 1 Habeler, Peter. The Lonely Victory: Mount Everest ‘78. 1979 Simon & We are most pleased to offer a number of items from the collection of American Schuster, NY, 1st, 8vo, pp.224, 23 color & 50 bw photos, map, white/blue mountaineer Pete Schoening (1927-2004). Pete is best remembered in boards; bookplate Ex Libris Pete Schoening & his name in pencil, dj w/ edge mountaineering circles for performing ‘The Belay’ during the dramatic descent wear, vg-, cloth vg+. #9709, $25.- of K2 by the Third American Karakoram Expedition in 1953. Pete’s heroics The first oxygenless ascent of Everest in 1978 with Messner. This is the US saved six men. However, Pete had many other mountain adventures, before and edition of ‘Everest: Impossible Victory’. Neate H01, SB H01, Yak H06. after K2, including: numerous climbs with Fred Beckey (1948-49), Mount Herrligkoffer, Karl. Nanga Parbat: The Killer Mountain. 1954 Knopf, NY, Saugstad (1st ascent, 1951), Mount Augusta (1st ascent) and King Peak (2nd & 1st, 8vo, pp.xx, 263, viii, 56 bw photos, 6 maps, appendices, blue cloth; book- 3rd ascents, 1952), Gasherburm I/Hidden Peak (1st ascent, 1958), McKinley plate Ex Libris Pete Schoening, dj spine faded, edge wear, vg, cloth bookplate, (1960), Mount Vinson (1st ascent, 1966), Pamirs (1974), Aconcagua (1995), vg. #9744, $35.- Kilimanjaro (1995), Everest (1996), not to mention countless climbs in the Summarizes the early attempts on Nanga Parbat from Mummery in 1895 and Pacific Northwest. -

Human Factors in High-Altitude Mountaineering

Journal of Human Performance in Extreme Environments Volume 12 Issue 1 Article 1 Published online: 5-8-2015 Human Factors in High-Altitude Mountaineering Christopher D. Wickens Alion Science and Technology, [email protected] John W. Keller Alion Science and Technology, [email protected] Christopher Shaw Alion Science and Technology, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/jhpee Part of the Industrial and Organizational Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Wickens, Christopher D.; Keller, John W.; and Shaw, Christopher (2015) "Human Factors in High-Altitude Mountaineering," Journal of Human Performance in Extreme Environments: Vol. 12 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. DOI: 10.7771/2327-2937.1065 Available at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/jhpee/vol12/iss1/1 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. This is an Open Access journal. This means that it uses a funding model that does not charge readers or their institutions for access. Readers may freely read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full texts of articles. This journal is covered under the CC BY-NC-ND license. Human Factors in High-Altitude Mountaineering Christopher D. Wickens, John W. Keller, and Christopher Shaw Alion Science and Technology Abstract We describe the human performance and cognitive challenges of high altitude mountaineering. The physical (environmental) and internal (health) stresses are first described, followed by the motivational factors that lead people to climb. The statistics of mountaineering accidents in the Himalayas and Alaska are then described. -

Lesson 1: Mount Everest Lesson Plan

Lesson 1: Mount Everest Lesson Plan Use the Mount Everest PowerPoint presentation in conjunction with this lesson. The PowerPoint presentation contains photographs and images and follows the sequence of the lesson. If required, this lesson can be taught in two stages; the first covering the geography of Mount Everest and the second covering the successful 1953 ascent of Everest by Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay. Key questions Where is Mount Everest located? How high is Mount Everest? What is the landscape like? How do the features of the landscape change at higher altitude? What is the weather like? How does this change? What are conditions like for people climbing the mountain? Who were Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay? How did they reach the summit of Mount Everest? What did they experience during their ascent? What did they do when they reached the summit? Subject content areas Locational knowledge: Pupils develop contextual knowledge of the location of globally significant places. Place knowledge: Communicate geographical information in a variety of ways, including writing at length. Interpret a range of geographical information. Physical geography: Describe and understand key aspects of physical geography, including mountains. Human geography: Describe and understand key aspects of human geography, including land use. Geographical skills and fieldwork: Use atlases, globes and digital/computer mapping to locate countries and describe features studied. Downloads Everest (PPT) Mount Everest factsheet for teachers -

Current Affairs and Answer Sheet

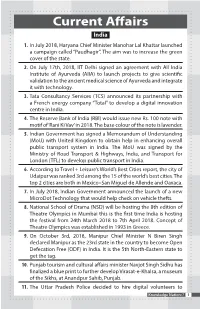

Current Affairs India 1. In July 2018, Haryana Chief Minister Manohar Lal Khattar launched a campaign called “Paudhagir”. The aim was to increase the green cover of the state. 2. On July 17th, 2018, IIT Delhi signed an agreement with All India Institute of Ayurveda (AIIA) to launch projects to give scientific validation to the ancient medical science of Ayurveda and integrate it with technology. 3. Tata Consultancy Services (TCS) announced its partnership with a French energy company “Total” to develop a digital innovation centre in India. 4. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) would issue new Rs. 100 note with motif of ‘Rani Ki Vav’ in 2018. The base colour of the note is lavender. 5. Indian Government has signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with United Kingdom to obtain help in enhancing overall public transport system in India. The MoU was signed by the Ministry of Road Transport & Highways, India, and Transport for London (TFL) to develop public transport in India. 6. According to Travel + Leisure’s World’s Best Cities report, the city of Udaipur was ranked 3rd among the 15 of the world’s best cities. The top 2 cities are both in Mexico–San Miguel de Allende and Oaxaca. 7. In July 2018, Indian Government announced the launch of a new MicroDot Technology that would help check on vehicle thefts. 8. National School of Drama (NSD) will be hosting the 8th edition of Theatre Olympics in Mumbai this is the first time India is hosting the festival from 24th March 2018 to 7th April 2018. -

Scholar Mountaineers, by Wilfrid Noyce. 164 Pages, with 12 Full- Page Illustrations and Wood-Engravings by R

Scholar Mountaineers, by Wilfrid Noyce. 164 pages, with 12 full- page illustrations and wood-engravings by R. Taylor. London: Dennis Dobson, 1950. Price, 12/6. What does the title Scholar Mountaineers lead one to expect? Maybe a series of essays about dons who have climbed, or an account of the climbers who have written scholarly works on the history and litera ture of mountaineering. Instead of either of these, Wilfrid Noyce has given us, under this title, a dozen brief, informal studies of figures whom he describes as “Pioneers of Parnassus”: Dante, Petrarch, Rousseau, De Saussure, Goethe, William and Dorothy Wordsworth, Keats, Ruskin, Leslie Stephen, Nietzsche, Pope Pius XI and Captain Scott. Each of them is studied “simply in relation to mountains”; each is considered as having made “a peculiar con tribution to a certain feeling in us.” Such is the author’s interest in them (and, of course, in mountains) that a reader is soon prepared to suppress the little question that nags at first: How many were “scholars,” and how many were “mountaineers”? Reading on, one becomes more and more interested in these selective treatments of the “Pioneers,” and in the differentiation of attitudes which they expressed or—in most cases quite unintention ally—fostered. Dante appears, for example, as “the trembling and unwieldy novice” who “comes near to wrecking the whole expedi tion through Hell”; and Keats is detected in a moment of what seems to be bravado—composing a sonnet on the summit of Ben Nevis. The discrimination of various attitudes toward -

1953 Conquest of Mount Everest

1953 Conquest of Mount Everest Mount Everest is in the Himalaya mountain range located between Nepal and Tibet, an autonomous region of China. At 8,849 meters (29,032 feet), it is considered the tallest point on Earth. In the 19th century, the mountain was named after George Everest, a former Surveyor General of India. The Tibetan name is Chomolungma, which means “Mother Goddess of the World.” The Nepali name is Sagarmatha. The 1953 British Mount Everest expedition was the ninth to attempt the first ascent and the first confirmed to have succeeded when Sherpa Tenzing Norgay and (later Sir) Edmund Hillary reached the summit on 29 May 1953. Led by Colonel John Hunt, it was organised and financed by the Joint Himalayan Committee. News of the expedition's success reached London in time to be released on the morning of Queen Elizabeth II's coronation on 2nd June. The conquest of Everest caught the imagination of the world. So, there are many commemorative & souvenir issues & first day covers. Consequently, it can make a good philatelic theme. This display shows just a small selection of what is available. This Indian first day cover shows a photo, taken by Edmund Hillary, of Sherpa Tenzing Norgay on the summit. Postcard - Edmund Hillary, Tenzing Norgay & Sir John Hunt’s Expedition Team Sir John Hunt (L), leader of the British Everest expedition, and Sir Edmund Hillary (R) arrive at Lancaster House for reception being given in their honour. Earlier they had been received by Queen Elizabeth who knighted the two men. Edmund Hilary Quotes “People do not decide to become extraordinary. -

The Modernisation of Elite British Mountaineering

The Modernisation of Elite British Mountaineering: Entrepreneurship, Commercialisation and the Career Climber, 1953-2000 Thomas P. Barcham Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of De Montfort University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Submission date: March 2018 Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................................... 4 Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................................... 5 Table of Abbreviations and Acronyms .................................................................................................... 6 Table of Figures ....................................................................................................................................... 7 Chapter 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 8 Literature Review ............................................................................................................................ 14 Definitions, Methodology and Structure ........................................................................................ 29 Chapter 2. 1953 to 1969 - Breaking a New Trail: The Early Search for Earnings in a Fast Changing Pursuit ..................................................................................................................................................