THE RESONANCE of EXPLORATION by Patrick Cassidy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antarctic Peninsula

Hucke-Gaete, R, Torres, D. & Vallejos, V. 1997c. Entanglement of Antarctic fur seals, Arctocephalus gazella, by marine debris at Cape Shirreff and San Telmo Islets, Livingston Island, Antarctica: 1998-1997. Serie Científica Instituto Antártico Chileno 47: 123-135. Hucke-Gaete, R., Osman, L.P., Moreno, C.A. & Torres, D. 2004. Examining natural population growth from near extinction: the case of the Antarctic fur seal at the South Shetlands, Antarctica. Polar Biology 27 (5): 304–311 Huckstadt, L., Costa, D. P., McDonald, B. I., Tremblay, Y., Crocker, D. E., Goebel, M. E. & Fedak, M. E. 2006. Habitat Selection and Foraging Behavior of Southern Elephant Seals in the Western Antarctic Peninsula. American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting 2006, abstract #OS33A-1684. INACH (Instituto Antártico Chileno) 2010. Chilean Antarctic Program of Scientific Research 2009-2010. Chilean Antarctic Institute Research Projects Department. Santiago, Chile. Kawaguchi, S., Nicol, S., Taki, K. & Naganobu, M. 2006. Fishing ground selection in the Antarctic krill fishery: Trends in patterns across years, seasons and nations. CCAMLR Science, 13: 117–141. Krause, D. J., Goebel, M. E., Marshall, G. J., & Abernathy, K. (2015). Novel foraging strategies observed in a growing leopard seal (Hydrurga leptonyx) population at Livingston Island, Antarctic Peninsula. Animal Biotelemetry, 3:24. Krause, D.J., Goebel, M.E., Marshall. G.J. & Abernathy, K. In Press. Summer diving and haul-out behavior of leopard seals (Hydrurga leptonyx) near mesopredator breeding colonies at Livingston Island, Antarctic Peninsula. Marine Mammal Science.Leppe, M., Fernandoy, F., Palma-Heldt, S. & Moisan, P 2004. Flora mesozoica en los depósitos morrénicos de cabo Shirreff, isla Livingston, Shetland del Sur, Península Antártica, in Actas del 10º Congreso Geológico Chileno. -

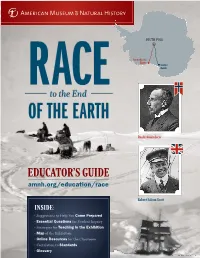

Educator's Guide

SOUTH POLE Amundsen’s Route Scott’s Route Roald Amundsen EDUCATOR’S GUIDE amnh.org/education/race Robert Falcon Scott INSIDE: • Suggestions to Help You Come Prepared • Essential Questions for Student Inquiry • Strategies for Teaching in the Exhibition • Map of the Exhibition • Online Resources for the Classroom • Correlation to Standards • Glossary ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS Who would be fi rst to set foot at the South Pole, Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen or British Naval offi cer Robert Falcon Scott? Tracing their heroic journeys, this exhibition portrays the harsh environment and scientifi c importance of the last continent to be explored. Use the Essential Questions below to connect the exhibition’s themes to your curriculum. What do explorers need to survive during What is Antarctica? Antarctica is Earth’s southernmost continent. About the size of the polar expeditions? United States and Mexico combined, it’s almost entirely covered Exploring Antarc- by a thick ice sheet that gives it the highest average elevation of tica involved great any continent. This ice sheet contains 90% of the world’s land ice, danger and un- which represents 70% of its fresh water. Antarctica is the coldest imaginable physical place on Earth, and an encircling polar ocean current keeps it hardship. Hazards that way. Winds blowing out of the continent’s core can reach included snow over 320 kilometers per hour (200 mph), making it the windiest. blindness, malnu- Since most of Antarctica receives no precipitation at all, it’s also trition, frostbite, the driest place on Earth. Its landforms include high plateaus and crevasses, and active volcanoes. -

Thesis Template

Thinking with photographs at the margins of Antarctic exploration A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Canterbury by Kerry McCarthy University of Canterbury 2010 Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................... 2 List of Figures and Tables ............................................................................................ 5 Acknowledgments .......................................................................................................... 6 Abstract ........................................................................................................................... 7 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 9 1.1 Thinking with photographs ....................................................................... 10 1.2 The margins ............................................................................................... 14 1.3 Antarctic exploration ................................................................................. 16 1.4 The researcher ........................................................................................... 20 1.5 Overview ................................................................................................... 22 2 An unauthorised genealogy of thinking with photographs .............................. 27 2.1 The -

February 2019 MEET SHAPE CLIENTS COBAN and KRISTIAN

… An Extraordinary Place on a Path to Prosperity Issue 73 February 2019 MEET SHAPE CLIENTS COBAN AND KRISTIAN t Helena Active Participation in Enterprise (SHAPE) aims to promote the rights and wellbeing of people with disabilities in all spheres of society and also to increase awareness. Their training programmes offer opportunities for structured work or supported employment. The focus of their service is Sto enhance employability and to support people with disabilities to achieve their maximum potential. Read the interesting stories of two SHAPE Clients, Coban and Kristian. Coban Scott-John Kristian Green y name is Coban Scott-John and I was born in Stanley on the Falkland Islands in 2001. y name is Kristian Green and I was born on At the age of two I was diagnosed in Ascension Island on 16 February 2001. At Guy’s Hospital in London, UK, as being two weeks old I was flown to the UK and Mautistic. I moved to St Helena at the age of 12 and was diagnosed in the John Radcliffe attended Prince Andrew School. I have been on holidays MHospital, Oxford, as having Down syndrome. I attended to St Helena before and always enjoy my time here. Two Boats School on Ascension until I was 16 years old. I returned to St Helena for good in January 2017. I attend SHAPE twice a week under the Carraresi programme. I am transitioning to SHAPE for when I leave I now attend Prince Andrew School which I really enjoy. I school in September this year. At SHAPE, I engage in a like reading, writing, Art, Maths, English, ICT and I love variety of activities including learning life skills and swimming. -

Scott's Discovery Expedition

New Light on the British National Antarctic Expedition (Scott’s Discovery Expedition) 1901-1904. Andrew Atkin Graduate Certificate in Antarctic Studies (GCAS X), 2007/2008 CONTENTS 1 Preamble 1.1 The Canterbury connection……………...………………….…………4 1.2 Primary sources of note………………………………………..………4 1.3 Intent of this paper…………………………………………………...…5 2 Bernacchi’s road to Discovery 2.1 Maria Island to Melbourne………………………………….…….……6 2.2 “.…that unmitigated fraud ‘Borky’ ……………………….……..….….7 2.3 Legacies of the Southern Cross…………………………….…….…..8 2.4 Fellowship and Authorship………………………………...…..………9 2.5 Appointment to NAE………………………………………….……….10 2.6 From Potsdam to Christchurch…………………………….………...11 2.7 Return to Cape Adare……………………………………….….…….12 2.8 Arrival in Winter Quarters-establishing magnetic observatory…...13 2.9 The importance of status………………………….……………….…14 3 Deeds of “Derring Doe” 3.1 Objectives-conflicting agendas…………………….……………..….15 3.2 Chivalrous deeds…………………………………….……………..…16 3.3 Scientists as Heroes……………………………….…….……………19 3.4 Confused roles……………………………….……..………….…...…21 3.5 Fame or obscurity? ……………………………………..…...….……22 2 4 “Scarcely and Exhibition of Control” 4.1 Experiments……………………………………………………………27 4.2 “The Only Intelligent Transport” …………………………………….28 4.3 “… a blasphemous frame of mind”……………………………….…32 4.4 “… far from a picnic” …………………………………………………34 4.5 “Usual retine Work diggin out Boats”………...………………..……37 4.6 Equipment…………………………………………………….……….38 4.8 Reflections on management…………………………………….…..39 5 “Walking to Christchurch” 5.1 Naval routines………………………………………………………….43 -

We Look for Light Within

“We look for light from within”: Shackleton’s Indomitable Spirit “For scientific discovery, give me Scott; for speed and efficiency of travel, give me Amundsen; but when you are in a hopeless situation, when you are seeing no way out, get down on your knees and pray for Shackleton.” — Raymond Priestley Shackleton—his name defines the “Heroic Age of Antarctica Exploration.” Setting out to be the first to the South Pole and later the first to cross the frozen continent, Ernest Shackleton failed. Sent home early from Robert F. Scott’s Discovery expedition, seven years later turning back less than 100 miles from the South Pole to save his men from certain death, and then in 1914 suffering disaster at the start of the Endurance expedition as his ship was trapped and crushed by ice, he seems an unlikely hero whose deeds would endure to this day. But leadership, courage, wisdom, trust, empathy, and strength define the man. Shackleton’s spirit continues to inspire in the 100th year after the rescue of the Endurance crew from Elephant Island. This exhibit is a learning collaboration between the Rauner Special Collections Library and “Pole to Pole,” an environmental studies course taught by Ross Virginia examining climate change in the polar regions through the lens of history, exploration and science. Fifty-one Dartmouth students shared their research to produce this exhibit exploring Shackleton and the Antarctica of his time. Discovery: Keeping Spirits Afloat In 1901, the first British Antarctic expedition in sixty years commenced aboard the Discovery, a newly-constructed vessel designed specifically for this trip. -

Sir Clements R. Markham 1830-1916

Sir Clements R. Markham 1830-1916 ‘BLUE PLAQUES’ adorn the houses of south polar explorers James Clark Ross, Robert Falcon Scott, Edward Adrian Wilson, Sir Ernest H. Shackleton, and, at one time, Captain Laurence Oates (his house was demolished and the plaque stored away). If Sir Clements Markham had not lived, it’s not unreasonable to think that of these only the one for Ross would exist today. Markham was the Britain’s great champion of polar exploration, particularly Antarctic exploration. Markham presided over the Sixth International Geographical Congress in 1895, meeting in London, and inserted the declaration that “the exploration of the Antarctic Regions is the greatest piece of geographical exploration still to be undertaken.” The world took notice and eyes were soon directed South. Markham’s great achievement was the National Antarctic Expedition (Discovery 1901-04) for which he chose Robert Falcon Scott as leader. He would have passed on both Wilson and Shackleton, too. When Scott contemplated heading South again, it was Markham who lent his expertise at planning, fundraising and ‘gentle arm-twisting.’ Without him, the British Antarctic Expedition (Terra Nova 1910-13) might not have been. As a young man Markham was in the Royal Navy on the Pacific station and went to the Arctic on Austin’s Franklin Search expedition of 1850-51. He served for many years in the India Office. In 1860 he was charged with collecting cinchona trees and seeds in the Andes for planting in India thus assuring a dependable supply of quinine. He accompanied Napier on the Abyssinian campaign and was present at the capture of Magdala. -

A History of Tourism, Leisure and Adventure in the Antarctic and Sub-Antarctic, C.1895 to Present

A History of Tourism, Leisure and Adventure in the Antarctic and Sub-Antarctic, c.1895 to Present by Wouter Pierre Hanekom Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of History in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Prof Sandra Scott Swart April 2014 Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za Plagiarism Declaration By submitting this dissertation electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that the reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe on any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Signature: Date: Copyright © 2014 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved ii Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract This thesis deals with the nature and historical development of tourism and leisure activities that have been conducted within the Antarctic and sub-Antarctic regions from 1895 to present. First, it traces the brief history of human involvement with the Antarctic continent, which culminated in a surge of ostensibly scientific exploration with jingoistic overtones which has become widely known as the ‘Heroic Age’ of Antarctic exploration. These explorers’ adventures, taken up by the popular press and promoted by jingoistic governments, popularised a particular conception of the continent to the point where people imagined going to see it for themselves, vicariously reliving their heroes’ adventures in the form of tourism. The rise of formal governance on the Antarctic is then traced and used to explain how this provided for regular tourist activities to commence since the mid-1960s. -

The Centenary of the Scott Expedition to Antarctica and of the United Kingdom’S Enduring Scientific Legacy and Ongoing Presence There”

Debate on 18 October: Scott Expedition to Antarctica and Scientific Legacy This Library Note provides background reading for the debate to be held on Thursday, 18 October: “the centenary of the Scott Expedition to Antarctica and of the United Kingdom’s enduring scientific legacy and ongoing presence there” The Note provides information on Antarctica’s geography and environment; provides a history of its exploration; outlines the international agreements that govern the territory; and summarises international scientific cooperation and the UK’s continuing role and presence. Ian Cruse 15 October 2012 LLN 2012/034 House of Lords Library Notes are compiled for the benefit of Members of the House of Lords and their personal staff, to provide impartial, politically balanced briefing on subjects likely to be of interest to Members of the Lords. Authors are available to discuss the contents of the Notes with the Members and their staff but cannot advise members of the general public. Any comments on Library Notes should be sent to the Head of Research Services, House of Lords Library, London SW1A 0PW or emailed to [email protected]. Table of Contents 1.1 Geophysics of Antarctica ....................................................................................... 1 1.2 Environmental Concerns about the Antarctic ......................................................... 2 2.1 Britain’s Early Interest in the Antarctic .................................................................... 4 2.2 Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration ....................................................................... -

Herbert Ponting; Picturing the Great White South

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2014 Herbert Ponting; Picturing the Great White South Maggie Downing CUNY City College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/328 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The City College of New York Herbert Ponting: Picturing the Great White South Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts of the City College of the City University of New York. by Maggie Downing New York, New York May 2014 Dedicated to my Mother Acknowledgments I wish to thank, first and foremost my advisor and mentor, Prof. Ellen Handy. This thesis would never have been possible without her continuing support and guidance throughout my career at City College, and her patience and dedication during the writing process. I would also like to thank the rest of my thesis committee, Prof. Lise Kjaer and Prof. Craig Houser for their ongoing support and advice. This thesis was made possible with the assistance of everyone who was a part of the Connor Study Abroad Fellowship committee, which allowed me to travel abroad to the Scott Polar Research Institute in Cambridge, UK. Special thanks goes to Moe Liu- D'Albero, Director of Budget and Operations for the Division of the Humanities and the Arts, who worked the bureaucratic college award system to get the funds to me in time. -

Scurvy? Is a Certain There Amount of Medical Sure, for Know That Sheds Light on These Questions

J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2013; 43:175–81 Paper http://dx.doi.org/10.4997/JRCPE.2013.217 © 2013 Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh The role of scurvy in Scott’s return from the South Pole AR Butler Honorary Professor of Medical Science, Medical School, University of St Andrews, Scotland, UK ABSTRACT Scurvy, caused by lack of vitamin C, was a major problem for polar Correspondence to AR Butler, explorers. It may have contributed to the general ill-health of the members of Purdie Building, University of St Andrews, Scott’s polar party in 1912 but their deaths are more likely to have been caused by St Andrews KY16 9ST, a combination of frostbite, malnutrition and hypothermia. Some have argued that Scotland, UK Oates’s war wound in particular suffered dehiscence caused by a lack of vitamin C, but there is little evidence to support this. At the time, many doctors in Britain tel. +44 (0)1334 474720 overlooked the results of the experiments by Axel Holst and Theodor Frølich e-mail [email protected] which showed the effects of nutritional deficiencies and continued to accept the view, championed by Sir Almroth Wright, that polar scurvy was due to ptomaine poisoning from tainted pemmican. Because of this, any advice given to Scott during his preparations would probably not have helped him minimise the effect of scurvy on the members of his party. KEYWORDS Polar exploration, scurvy, Robert Falcon Scott, Lawrence Oates DECLaratIONS OF INTERESTS No conflicts of interest declared. INTRODUCTION The year 2012 marked the centenary of Robert -

Catalogue 48: June 2013

Top of the World Books Catalogue 48: June 2013 Mountaineering Fiction. The story of the struggles of a Swiss guide in the French Alps. Neate X134. Pete Schoening Collection – Part 1 Habeler, Peter. The Lonely Victory: Mount Everest ‘78. 1979 Simon & We are most pleased to offer a number of items from the collection of American Schuster, NY, 1st, 8vo, pp.224, 23 color & 50 bw photos, map, white/blue mountaineer Pete Schoening (1927-2004). Pete is best remembered in boards; bookplate Ex Libris Pete Schoening & his name in pencil, dj w/ edge mountaineering circles for performing ‘The Belay’ during the dramatic descent wear, vg-, cloth vg+. #9709, $25.- of K2 by the Third American Karakoram Expedition in 1953. Pete’s heroics The first oxygenless ascent of Everest in 1978 with Messner. This is the US saved six men. However, Pete had many other mountain adventures, before and edition of ‘Everest: Impossible Victory’. Neate H01, SB H01, Yak H06. after K2, including: numerous climbs with Fred Beckey (1948-49), Mount Herrligkoffer, Karl. Nanga Parbat: The Killer Mountain. 1954 Knopf, NY, Saugstad (1st ascent, 1951), Mount Augusta (1st ascent) and King Peak (2nd & 1st, 8vo, pp.xx, 263, viii, 56 bw photos, 6 maps, appendices, blue cloth; book- 3rd ascents, 1952), Gasherburm I/Hidden Peak (1st ascent, 1958), McKinley plate Ex Libris Pete Schoening, dj spine faded, edge wear, vg, cloth bookplate, (1960), Mount Vinson (1st ascent, 1966), Pamirs (1974), Aconcagua (1995), vg. #9744, $35.- Kilimanjaro (1995), Everest (1996), not to mention countless climbs in the Summarizes the early attempts on Nanga Parbat from Mummery in 1895 and Pacific Northwest.