Spicilegium Historicum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NOWOTWORY Journal of Oncology 2017, Volume 67, Number 6, 321–335 DOI: 10.5603/NJO.2017.0054 © Polskie Towarzystwo Onkologiczne ISSN 0029–540X

NOWOTWORY Journal of Oncology 2017, volume 67, number 6, 321–335 DOI: 10.5603/NJO.2017.0054 © Polskie Towarzystwo Onkologiczne ISSN 0029–540X www.nowotwory.edu.pl The Nowotwory journal over the last 95 years (1923–2018) Edward Towpik1, 2, Wojciech M. Wysocki3 ‘The quarterly Nowotwory, its contributing authors and editorial committees have laid down the intellectual foundations of oncology in Poland’. Professor Hanna Kołodziejska Editor in Chief during 1974–1991 Launching of the journal and its development One of the first global initiatives for publishing a perio- dical devoted to the fight against cancer arose in Poland back in 1906, when both Dr Mikołaj Rejchmann and Dr Józef Jaworski from Warsaw set up an Anti-Cancer Committee (Komitet do Walki z Rakiem). One of its aims was to launch a journal, however this proved impossible due to the unfa- vourable conditions prevailing at that time. When Poland regained its independence, organising anti-cancer policies again became a priority. In July 1921, an Polish Anti-Cancer Committee (Polski Komitet do Zwalcza- nia Raka) in Warsaw came into being. Despite scant resour- ces it rapidly and enthusiastically started its operations. This was reflected by publishing a journal entitled The Bulletin of the Polish Anti-Cancer Committee (Biuletyn Polskiego Komi- tetu do Zwalczania Raka). The first edition was published in 1923, whose editor was Dr Stefan Sterling-Okuniewski, MD. At that time, this really was a pioneering endeavour as there were only 5 other such journals dedicated solely to the anti-cancer campaign in the world: the German Zeit- schrift für Krebsforschung (1903), the Japanese Gann (1907), the French Bulletin de l’Association Francaise pour l’Etude du Cancer (1909), the Italian Tumori (1911) and from the USA Journal of Cancer Research (1916)1. -

Marian Brudzisz, C.SS.R

SHCSR 61 (2013) 57-121 MARIAN BRUDZISZ , C.SS.R. REDEMPTORIST MINISTRY AMONG THE POLISH IN THE SOVIET SOCIALIST REPUBLICS OF LITHUANIA AND BYELORUSSIA, 1939-1990* Introduction ; 1. – The foundation of the Redemptorists in Wilno-Po śpieszka as their base for the apostolate ; 2. – The pastoral activities of the Redemptorist Polish community in Wilno-Po śpieszka ; 2.1 The Po śpieszka Redemptorists in the early days of World War II ; 2.2 In Wilno and the Wilno Region – under the first Soviet occupation ; 2.3 Po śpieszka under the German occupation ; 2.3.1 The Pasto- ral ministry of the Redemptorists continues ; 2.3.2 Father Jan Dochniak’s mission in Prozoroki, Byelorussia ; 2.3.3 Help Given to the Jewish Population ; 2.3.4 De- fending the Polish nation: correspondence, clandestine courses, and the resi- stance movement ; 2.3.5 Away with the Church and religious congregations ; 2.3.6 Po śpieszka in the hands of Archbishop Mieczysław Reinys and «Ostland» ; 2.3.7 The Redemptorists after their return to Po śpieszka in 1943 ; 2.3.8 Social Care ; 3. – The Redemptorists’ Apostolic Ministry during the dispersion of the com- munity, 1942-1944 ; 3.1 Father Franciszek Świ ątek’s ministry 1942-1944 ; 3.2 Father Ludwik Fr ąś , ministry 1942-1944 ; 3.3 Father Jan Dochniak, ministry 1942-1944 ; 3.4 Father Stanislaw Grela, ministry 1942-1944 ; 4. – The second Soviet occupation and “repatriation” ; 5. – Thirty years of Father Franciszek Świ ątek’s continued apostolate among Poles under the Soviet Regime, 1946-1976 ; 5.1 Pas- toral work in Po śpieszka and Wołokumpia, 1946-1951 ; 5.2 His «secret mission» to Novogródek ; 5.3 Father Świ ątek in Brasław, Byelorussia, 1952-1959 ; 5.4 Fa- ther Świ ątek in Czarny Bór (Lithuania), and briefly in Poland, 1959-1964 ; 5.5 Father Świ ątek’s last twelve years, 1964-1976 ; 6. -

Almanach Historyczny

Almanach Historyczny Wydanie publikacji finansowane w ramach programu „Wsparcie dla czasopism naukowych” w latach 2019–2020 (umowa nr 290/WCN/2019/1) Almanach Historyczny Tom 22 Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jana Kochanowskiego Kielce 2020 Rada redakcyjna Michael D. Bailey, Wiesław Caban, Marek Derwich, Janusz Małłek, Witold Molik, Swietłana Mulina, Martin Nodl, Andrzej Nowak, Krzysztof Pilarczyk, Kazimierz Przyboś, Tadeusz Stegner, Andrzej Szwarc, Edward Walewander, Theodore R. Weeks Kolegium redakcyjne Krzysztof Bracha, Wiesław Caban, Jerzy Gapys (zastępca przewodniczącego), Lucyna Kostuch, Jacek Legieć (przewodniczący), Grzegorz Miernik, Jacek Pielas, Stanisław Wiech Stali recenzenci dr hab. prof. UJK Katarzyna Balbuza (UAM), dr hab. Larysa Bondar (Rosyjskie Państwowe Archiwum Historyczne w Petersburgu, Rosja), dr hab. Wiesław Bondyra (UMCS) ks. prof. zw. Waldemar Graczyk (UKSW), prof. zw. dr hab. Igor Hałagida ks. prof. dr hab. Janusz Ihnatowicz (University of St. Thomas, Huston) dr hab. prof. UŁ Witold Jarno, dr hab. prof. UŁ Jarosław Kita prof. dr hab. Ratislav Kožak (Uniwersytet Macieja Bela w Bańskiej Bystrzycy, Słowacja) dr hab., prof. UMCS Krzysztof Latawiec, dr hab. Tünde Lengyelová (Słowacka Akademia Nauk), dr hab., prof. UŁ Krzysztof Lesiakowski, dr hab., prof. UMCS Janusz Łosowski dr hab., prof. UP-H Dariusz Magier (UP-H w Siedlcach), prof. zw. dr hab. Jolanta M. Marszalska (UKSW), dr hab., prof. PAN Warszawa Magdalena Micińska prof. dr hab. Beata Możejko (UG), prof. zw. dr hab. Danuta Musiał (UMK) ks. prof. zw. dr hab. Jerzy Myszor (UŚ), prof. zw. dr hab. Eugeniusz Niebelski (KUL) prof. dr hab. Zdzisław Noga (UP w Krakowie), prof. dr hab. Hana Pátková (Uniwersytet Karola w Pradze, Czechy), dr hab. Patryk Pleskot (IPN Warszawa), dr hab. -

Professor Kazimierz Pelczar (1894–1943) Founder of an Organised Campaign Against Cancer in Vilnius 85 Years Ago

NOWOTWORY Journal of Oncology 2016, volume 66, number 5, 427–431 DOI: 10.5603/NJO.2016.0076 © Polskie Towarzystwo Onkologiczne ISSN 0029–540X In memoriam www.nowotwory.edu.pl Professor Kazimierz Pelczar (1894–1943) Founder of an organised campaign against cancer in Vilnius 85 years ago On a certain frosty day of winter in 1931 a group of and Professor of the Vilnius University (deceased in 2003), Vilnius residents, having faith in a better future for the treat- remembered him fondly with tears in his eyes. ment and care of cancer patients, founded a hospital with 10 beds on one of the floors of an old peoples’ home. This was Professor Pelczar’s education and personality 85 years ago. The founder was Professor Kazimierz Pelczar He was born on 2nd August 1894 at Truskawiec in the who became the institute’s Director until his death in 1943. Lvov region, being the son of Zenon and Maria Krasnodeb- sky; a prominent Polish intelligentsia family with connec- Who was Professor Kazimierz Pelczar tions to Cracow often noted in encyclopaedias. His wife was The Professor was a graduate from the Faculty of Medi- Janina Mossorow, a woman of captivating beauty closely cine at the Jagiellonian University in Krakow, subsequently related to an outstanding Polish physician, Joseph Dietl, who becoming a Professor at the Vilnius Stefan Batory University was a pioneer of Polish Balneotherapy, a Professor and Rec- and the Dean of the Faculty of Medicine together with be- tor of the Jagiellonian University and also a mayor Cracow. ing the Departmental Head of General and Experimental Professor Pelczar’s father was Professor Zenon Pelczar, the Pathology. -

Lb7jdbisi 3ML Jhfoifcrtt

lb7 J d b is i 3ML J H fo ifc rtt The Day I Didn’t Die by John M. Haffert LAF P.O. Box 50 Asbury, NJ, 08802 Nihil Obstat: Copies of the manuscript were sent u> five- bishops and to many outstanding Catholic authors and apostles in the U.S., England, and Austrailia. Two copies went to experts in Rome. Specific changes recommended during the ensuing six months were gratefully welcomed and followed. First Printing: 15,000 copies - 6/98 Printed in the USA by: The 101 Foundation, Inc. P.O. Box 151 Asbury, NJ 08802-0151 Phone: (908) 689-8792 Fax: (908) 689-1957 Copyright, 1998, by John M. Haffert. All rights reserved. ISBN: 1 890137-12-X "Write about what you are doing now." Above are the words the author believes to have heard during a near death experience on July 1, 1996. His major concern at that moment was the golden jubilee celebration of Our Lady of Fatima as Queen of the World and the decline of the Blue Army. He felt helpless to do much about either. But his heavenly visitors seemed to say that since he was about to write a letter to his sister in Carmel, he should begin with that. He felt relieved because much of what he would write seemed too personal and too delicate to be published in a book. Then a year and three months later, in a letter of Oct. 13, 1997, Pope John Paul II called the miracle of Fatima one of the greatest signs of our times because it brings us face to face with the great alternative facing the world, “the outcome of which," said the Pope, "depends upon our response." To encourage this response in the Blue Army, the author made the decision to publish what he had revealed in the letter to his sister in this book, the entire contents of which can be grasped pretty well from the table of contents, which includes keynote phrases from each chapter. -

Military Pharmacy and Medicine Pharmacy Military

Volume V • No. 1 ISSN 1898-6498 January –March • 2012 MILITARY PHARMACY • No. 1 • 2012 1 • 2012 • No. AND MEDICINE Volume V Volume • QUARTERLY INTERDISCIPLINARY JOURNAL • PHARMACY • MEDICINE • MEDICAL TECHNIQUE MILITARY PHARMACY AND MEDICINE PHARMACY MILITARY • ENVIRONMENT AND HEALTH • EDUCATION The Staff of the Military Center of Pharmacy and Medical Technology in Celestynow – Poland Druga strona okładki Volume 5, No 1 January - March, 2012 MILITARY PHARMACY AND MEDICINE Quarterly Interdisciplinary Journal of Military Centre of Pharmacy and Medical Technique in Celestynów on scientific socio-professional and training issues of Military Pharmacy and Medicine ISSN 1898-6498 MILITARY PHARMACY AND MEDICINE SCIENTIFIC BOARD Anyakora Chimezie, Nigeria prof. dr hab. Jerzy Mierzejewski, Poland Balbaa Mahmoud, Egypt prof. dr hab. Elżbieta Mikiciuk-Olasik, Poland prof. dr hab. Michał Bartoszcze, Poland Newcomb Andrew, Canada prof. dr hab. inż. Stanisław Bielecki, Poland prof. dr hab. Jerzy Z. Nowak, Poland Bisleri Gianluigi, Italy dr hab. Romuald Olszański, Poland Blumenfeld Zeev, Israel prof. dr hab. Daria Orszulak-Michalak, Poland dr hab. Kazimiera H. Bodek, Poland prof. dr hab. Krzysztof Owczarek, Poland Boonstra Tjeerd W, Netherlands prof. dr hab. Marek Paradowski, Poland Borcic Josipa, Croatia Perotti Daniela, Italy Cappelli Gianni, Italy Pivac Nela, Croatia Yifeng Chai, China Pizzuto Francesco, Italy Chowdhury Pritish K, India prof. dr hab. Janusz Pluta, Poland Costa Milton, Brasil Polat Gurbuz, Turkey prof. dr hab. inż. Krzysztof Czupryński, Poland Popescu Irinel, Romania Deckert Andreas, Germany Reddy G. Bhanuprakash, India Demeter Pal, Hungary prof. dr hab. Juliusz Reiss, Poland prof. dr hab. Adam Dziki, Poland Rodrigues Gabriel Sunil, India Ermakova Irina, Russia Rossi Roberto, Italy prof. -

Miejsce „Ludzkiej Rzeźni” Recenzent Maria Wardzyńska

Ponary miejsce „ludzkiej rzeźni” Recenzent Maria Wardzyńska Korekta Maria Aleksandrow Redakcja techniczna Andrzej Broniak Opracowanie graficzne Sylwia Szafrańska Zdjęcia Archiwum Instytutu Pamięci Narodowej Druk i oprawa Instytut Pamięci Narodowej © Copyright by Instytut Pamięci Narodowej Komisja Ścigania Zbrodni przeciwko Narodowi Polskiemu, 2011 © Copyright by Ministerstwo Spraw Zagranicznych Rzeczpospolitej Polskiej Departament Współpracy z Polonią, 2011 prof. UG dr hab. Piotr Niwiński prof. hab. dr. Piotr Niwiński prof. Piotr Niwiński Uniwersytet Gdański Gdansko Universiteto University of Gdańsk Instytut Politologii Politologijos Institutas Institute of Political Science Ponary Paneriai Ponary miejsce „ludzkiej „žmonių skerdynių“ the Place rzeźni” vieta of “Human Slaughter” 3 onary – to miejsce szczególne. Nieznane aneriai – ypatinga vieta. Nuodugniau ne onary is a special place. Unknown clos bliżej zarówno społeczeństwu polskiemu, pažintas nei lenkų visuomenės, nei kitų ša er both to the Polish people and people Pjak i mieszkańcom innych krajów, jedno Plių gyventojų žiaurios tragedijos simbolis. Pfrom other countries, at the same time cześnie symbolizujące wielką tragedię i okrucień Skirtingai negu kitos, didelių tragedijų pažymė symbolising great tragedy and cruelty. Relegated stwo. Przez lata spychane do niepamięci, w prze tos vietovės, kaip Pamario Piasnicos ir Špenga to oblivion over the years, in contrast to places ciwieństwie do miejsc równie wielkich tragedii, vos girios ar Mirties slėnis ties Bydgošče, Sobibor, of equally horrible tragedies, such as Piaśnica or jak lasy Piaśnickie czy Szpęgawskie na Pomorzu, Treblinka, ilgus metus stumiama į užmarštį. So Szpęgawskie forests in Pomerania, the Death Val Dolina Śmierci koło Bydgoszczy, Sobibór, Treblin vietų totalitarinio režimo nutylėta, mūsų kaimy ley near Bydgoszcz, Sobibor, and Treblinka. Ig ka. Przemilczane przez totalitarny reżim sowiec nų – vokiečių ir lietuvių – pamiršta. -

In the Footsteps of St. Paul of the Cross in Rome a Passionist Pilgrim’S Guide Lawrence Rywalt, C.P

In the Footsteps of St. Paul of the Cross in Rome A Passionist Pilgrim’s Guide Lawrence Rywalt, C.P. Cum permissu: Joachim Rego, C.P. Superior General 1st printing June 2017 Graphics: Andrea Marzolla Cover photograph: Statue of St. Paul of the Cross, St. Peter’s Basilica Congregation of the Passion of Jesus Christ In the Footsteps of St. Paul of the Cross in Rome A Passionist Pilgrim’s Guide Lawrence Rywalt, C.P. Curia Generalizia dei Passionisti, P.zza SS. Giovanni e Paolo 13 00184 Roma (RM) Table of Contents Introduction Casa mia! Casa mia! 5 Itinerary 1: The Celio Hill 1.1 The Basilica and Monastery of Sts. John and Paul 7 1.2 The Basilica of Santa Maria in Domnica (the “Navicella”) 10 1.3 The Hospice of the Most Holy Crucifix 12 1.4 The Basilica of St. John Lateran 15 Itinerary 2: The Esquiline Hill and the district of the “Monti” (hills) 2.1 The Basilica of St. Mary Major 17 2.2 The Church of the “Madonna ai Monti” 19 Itinerary 3: The Trastevere district 3.1 The Tiberina Island and the Church and the College of St. Bartholomew 21 3.2 The Hospital of San Gallicano 23 3.3 The Church of Santa Maria in Trastevere 28 Itinerary 4: The Lungotevere district and the Vatican 4.1 The “Ponte Sisto” Bridge and Hospice and Pilgrims’ Church of the Most Holy Trinity (SS. Trinità dei Pellegrini) 30 4.2 The Church of San Giovanni dei Fiorentini 33 4.3 St. Peter’s Basilica -- the Canons’ Chapel of the Immaculate Conception (“l’Immacolata” / dei Canonici) and the Statue of St. -

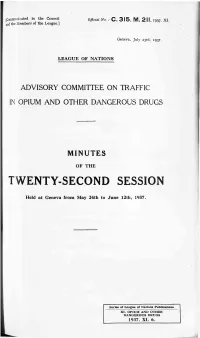

Twenty-Second Session

[Communicated to the Council Official No. : C . 3 1 5 . M , 2 1 1 . 1937. XI. and the Members of the League.] Geneva, July 23rd, 1937. LEAGUE OF NATIONS ADVISORY COMMITTEE ON TRAFFIC IN OPIUM AND OTHER DANGEROUS DRUGS MINUTES OF THE TWENTY-SECOND SESSION Held at Geneva from May 24th to June 12th, 1937. Series of League of Nations Publications XI. OPIUM AND OTHER DANGEROUS DRUGS 1937. XI. 6. CONTENTS. List o f M e m b e r s .................................................................................................................................................................................................................. y First MEETING (P riv a te ), M a y 2 4 th , 1937, a t 11 a.m . : 1171. W elcome to New M em bers .............................................................................................................................. g 1172. Election of th e C hairm an, V ice-C hairm an and R a p p o r te u r ................................................................ 8 1173. A ppointm ent of A s s e s s o rs ................................................................................................................................. 8 1174. Election of T hree M em bers of th e A genda S u b -C o m m itte e ................................................................ 8 1175. Adoption of the Agenda of the Session : Report of the Agenda Sub-Committee....................... 8 1176. Publicity of th e M eetings ................................................................................................................................. 8 Second M eeting (Public), May 25th, 1937, a t 11 a.m . : 1177. Resignation of M. von Heidenstam, Representative of Sweden. Decision of the Swedish G overnm ent n o t to seek F u rth e r R ep resen tatio n on th e C om m ittee .................................... 1178. Tribute to the Memory of Mr. Hardy, M. van W ettum and Mr. John D. Rockefeller............ -

Wilno – Krew I Łzy Ponary

Danuta Szyksznian-Ossowska ps. „Sarenka” WILNO – KREW I ŁZY PONARY Szczecin 2019 Redakcja: Jolanta Szyłkowska Korekta: Anna Cichy, Janina Kosman Projekt okładki: Michał Szyksznian Skład i łamanie: Iga Bańkowska Fotografie: zbiory prywatne Autorki, Michał Jabłoński, Tomasz Rychłowski Grafika: Agnieszka Gędek Obrazy: Ewa Siudowska Publikacja dofinansowana przez Polską Spółkę Gazownictwa Sp. z o.o. Dziękuję © Copyright by Danuta Szyksznian, 2019 przyjaciołom i wszystkim tym, którzy służyli mi pomocą, Wydanie II zmienione wspierając redakcyjny trud powstania tej książki Wydawca: Archiwum Państwowe w Szczecinie Autorka ISBN 978-83-66028-05-0 „ocalałeś nie po to aby żyć masz mało czasu trzeba dać świadectwo” Zbigniew Herbert, Przesłanie Pana Cogito Oddajemy do rąk czytelników drugie, rozszerzone wydanie książki Wilno – krew i łzy. Ponary autorstwa Danuty Szyksznian-Ossowskiej. Pani Danuta całe swoje życie poświęciła sprawie walki o wolną, niepodległą Polskę. Jako młoda osoba wstąpiła w szeregi ZWZ-AK, brała udział w Powstaniu Wileńskim, aresztowana przez NKWD, spędziła pół roku w łagrze. Od 1945 r. mieszka na Pomorzu Zachodnim, gdzie aktywnie działa w środowisku żołnierzy AK. Niniejsza publikacja dokumentuje terror i zbrodnie dokonane przez okupantów niemieckich i litewskich kolaborantów w więzieniu na Łukiszkach w Wilnie, a przede wszystkim w Ponarach. Zawiera wspomnienia świadków wydarzeń, ich rodzin oraz bogaty materiał ikonograficzny. Jest formą hołdu dla ofiar zbrodni na Wileńszczyźnie i przestrogą dla współczesnych pokoleń do czego może -

Kazimierz Pelczar (18941943), the Prominent Professor of Vilnius Stefan Batory University (To the 110Th Anniversary of His Birth)

ACTA MEDICA LITUANICA. 2004. VOLUME 11 No. 2. P. 6567 $# © Lietuvos moksløKazimierz akademija, Pelczar 2004 (18941943), the prominent professor of Vilnius Stefan Batory University © Lietuvos mokslø akademijos leidykla, 2004 Kazimierz Pelczar (18941943), the prominent professor of Vilnius Stefan Batory University (to the 110th anniversary of his birth) Rimgaudas Virgilijus Kazakevièius Department of Pathology, Forensic Medicine and Pharmacology, Medical Faculty, Vilnius University, M. K. Èiurlionio 21, LT-2009 Vilnius, Lithuania Kristyna Rotkeviè Institute of Oncology of Vilnius University, Santariðkiø 1, a Vilnius Lithuania cow Jagiellonian University. During World War I, in 19141915 he was in the Austrian army. He was taken prisoner by the Russian army and in 1915 1918 worked in the Red Cross sanitary service in Kiev and Moscow and in 19181920 in the sanitary service of Siberian Division. After its evacuation, through China and Japan, he got to Polish Army. In 19201923 K. Pelczar continued studies of medi- cine at Collegium Medicum of Cracow Jagiellonian University and in 1925 got the doctors degree. During studies he specialized in general and expe- rimental pathology with Prof. K. Klecky and in in- vestigations of pathology of metabolism with Prof. L. Marchlewski. In 19201930 he worked as assis- tent at the Department of General Pathology of Col- legium Medicum of Cracow University. In 1927 K. Pelczar specialized in hematology and in experi- mental transplantation of tumours with Prof. H. Auer Professor K. Pelczar, Head of Department of Ge- in Berlin. In 1928 he worked on probation at Pas- neral and Experimental Pathology of Medical Fa- teur Institute in Paris on biological research of culty at Stefan Batory University, the prominent on- malignant tumours and at Institute of Radium on cologist, was born 2 August 1894 in Truskawiec. -

Maksymilian Rose (1883–1937) – Pioneer of Brain Research, Professor of the Stefan Batory University in Vilnius1 DOI 10.25951/4231

Almanach Historyczny 2020, t. 22, s. 181–198 Małgorzata Przeniosło (Uniwersytet Jana Kochanowskiego w Kielcach) ORCID: 0000-0001-7487-9976 Piotr Kądziela (Uniwersytet Jana Kochanowskiego w Kielcach) ORCID: 0000-0001-8747-1558 Maksymilian Rose (1883–1937) – pioneer of brain research, Professor of the Stefan Batory University in Vilnius1 DOI 10.25951/4231 Streszczenie Maksymilian Rose (1883–1937) – pionier badań mózgu, profesor Uniwersytetu Stefana Batorego w Wilnie Maksymilian Rose nie był dotychczas przedmiotem zainteresowania badaczy. Urodził się w 1883 r. w Przemyślu, zmarł w 1937 r. w Wilnie. Studia medyczne odbył na Uniwersytecie Jagiellońskim, tu też kilka lat był asystentem. Z kolei na Uniwersytecie Warszawskim pracował jako docent. Zawodowo realizował się także w Niemczech i w Szwajcarii. W latach 1931–1937 kierował Katedrą Psychiatrii, następnie Katedrą Psychiatrii i Neurologii na Uniwersytecie Ste- fana Batorego w Wilnie. Do Wilna przeniósł z Warszawy kierowany przez siebie Polski Insty- tutu Badań Mózgu. Była to jedna z trzech działających wówczas tego typu placówek w Europie. Rose był wybitnym badaczem mózgu, dodatkowy rozgłos uzyskał dzięki podjęciu badań nad mózgiem Józefa Piłsudskiego przekazanym mu po śmierci Marszałka. Na gruncie polskim Rose był jednym z nielicznych międzywojennych profesorów uniwersytetów, którzy mając pocho- dzenie żydowskie, otrzymali własną katedrę. Słowa kluczowe: historia medycyny, polska nauka w okresie międzywojennym, profeso- rowie Uniwersytetu Stefana Batorego w Wilnie. 1 The paper analyzes source material collected during the implementation of the grant no. 0062/NPRH4/H1a/83/2015 of the National Program for the Development of Humanities. 182 Małgorzata Przeniosło, Piotr Kądziela Summary Professor Maksymilian Rose has not yet attracted any interest among historians.