Awareness, Acceptance and Attitude on HIV/AIDS: Perspectives of Students in a University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PS Rbs CPU Directory for Website February 2021.Xlsx

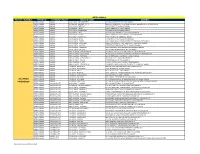

METRO MANILA PAYOUT CHANNELS PROVINCE CITY/MUNICIPALITY BRANCH NAME ADDRESS METRO MANILA MANILA H VILLARICA - BLUMENTRITT 1 1714 BLUMENTRITT ST. STA CRUZ MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA H VILLARICA - BLUMENTRITT 2 1601 COR. BLUEMNTRITT ST & RIZAL AVE BRGY 363,ZONE 037 STA CRUZ MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA H VILLARICA - BUSTILLOS 443 FIGUERAS ST. SAMPALOC MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA H VILLARICA - PACO 1 # 1122 PEDRO GIL ST., PACO MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA H VILLARICA - PADRE RADA 656 PADRE RADA ST TONDO MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA H VILLARICA - PRITIL 1 1835 NICOLAS ZAMORA ST TONDO BGY 86 MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA H VILLARICA - QUINTA 200 VILLALOBOS ST COR C PALANCA ST QUIAPO MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA H VILLARICA - SAMPALOC 1 1706 J. FAJARDO ST. SAMPALOC MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA HL VILLARICA - D JOSE 1574 D.JOSE ST STA. CRUZ NORTH,MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA HL VILLARICA - ESPAÑA 1664 ESPANA BLVD COR MA CRISTINA ST SAMPALOC EAST,MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA HL VILLARICA - LAON LAAN 1285 E. LAON LAAN ST., COR. MACEDA ST., SAMPALOC MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA HL VILLARICA - MACEDA 1758 RETIRO CORNER MACEDA ST. SAMPALOC MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA HL VILLARICA - PANDACAN 1922 J ZAMORA ST BRGY 851 ZONE 93 PANDACAN MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA HL VILLARICA - STA. ANA 1 3421-25 NEW PANADEROS ST. STA.ANA MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA HRV VILLARICA - ERMITA MANILA UYGUANGCO RD., BO. STO. NIÑO BRGY 187 TALA CALOOCAN METRO MANILA MANILA HRV VILLARICA - GAGALANGIN 2710 JUAN LUNA ST GAGALANGIN BRGY 185 ZONE 016 TONDO MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA HRV VILLARICA - HERMOSA 1157 B. HERMOSA ST. MANUGUIT TONDO MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA HRV VILLARICA - ILAYA MANILA #33 ARANETA ST. -

Cebu 1(Mun to City)

TABLE OF CONTENTS Map of Cebu Province i Map of Cebu City ii - iii Map of Mactan Island iv Map of Cebu v A. Overview I. Brief History................................................................... 1 - 2 II. Geography...................................................................... 3 III. Topography..................................................................... 3 IV. Climate........................................................................... 3 V. Population....................................................................... 3 VI. Dialect............................................................................. 4 VII. Political Subdivision: Cebu Province........................................................... 4 - 8 Cebu City ................................................................. 8 - 9 Bogo City.................................................................. 9 - 10 Carcar City............................................................... 10 - 11 Danao City................................................................ 11 - 12 Lapu-lapu City........................................................... 13 - 14 Mandaue City............................................................ 14 - 15 City of Naga............................................................. 15 Talisay City............................................................... 16 Toledo City................................................................. 16 - 17 B. Tourist Attractions I. Historical........................................................................ -

Profile of the Board of Directors

PROFILE OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS Atty. Baldomero C. Estenzo DIRECTOR Age: 76 Academic Qualification: Graduate from the University of San Carlos in Cebu City in 1963 with a degree of Bachelor of Science in Commerce major in Accounting. Graduate from the University of the Philippines in 1968 with a degree of Bachelor of Laws. Ranked No. 5 in the list of graduating students from the College of Law. Experience: 1965‐1969‐ Auditing Aide & Reviewer Bureau of Internal Revenue Department of Finance, Manila 1969‐1979 Practicing Lawyer in Cebu Commercial Law Lecturer Cebu Central Colleges 1979‐1990 Head of Legal Unit of San Miguel Corporation, Mandaue City 1990‐2004 Assistant Vice President & Deputy Gen. Counsel of San Miguel Corporation 2006 Vice President & Deputy General Counsel of San Miguel Corporation 2007‐Present Executive Vice Chancellor & Dean, College of Law of the University of Cebu Ms. Candice G. Gotianuy DIRECTOR Age: 46 Academic Qualification: AB in Political Science, Ateneo de Manila University Masters in Education, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA Experience: President, University of Cebu Medical Center Managing Director, St. Vincent’s General Hospital President, College of Technological Sciences Chancellor, University of Cebu ‐ Banilad Campus ‐ Main Campus ‐ Maritime Education & Training Center ‐ Lapu‐lapu and Mandaue Campus Treasurer, Chelsea Land Development Corporation Vice‐President, Gotianuy Realty Corporation Director, Cebu Central Realty Corporation (E‐Mall) Director, Visayan Surety & Insurance Corporation Director, -

PACU Newsletter Opportunities”

Summer Fellowship at the Bayleaf PACU continues the "Summer Fellowship" pioneered by immediate past president Peter P. Laurel.At this event, PACU members come together to bond, enjoy, dine and dance just for an evening away from the rigors of the administrative and academic grind. PACU At The Forefront Of Academic And Educational Updates PACU: Reaching out... (cover story) We were all happy that Ushering academic year 2012- 2013, the PACU program committee facilitated and conducted three academic management seminars at Sun Life Financials, proposed interesting possibilities on attended and participated on January 24- 25, 2013. Aptly titled Dr. Butchie Lim Ayuyao graced the occasion. in different regions of the country : National Capital Region, Quezon Province, Luzon and Cebu City, for the PACU members in the “Establishing and Maintaining School Endowments and Grants”. “Preparing HEI’s for the Challenges Ahead: Addressing regions of Visayas and Mindanao. Concerns on K-12, ASEAN 2015 and Quality Assurance”, the Our thanks reach out to The third academic management seminar was conducted seminar delivered timely updates on current critical concerns. Dr. Gerry Cao who TIP Chairman, Dr. Tessie Quirino and TIP President Beth Enverga University Foundation hosted the seminar entitled at the University of Cebu, Banilad Campus. Welcomed by the Although open to all interested parties, the seminar was meant to gamely hosted the Lahoz welcomed PACU and over 172 participants in the first “Leveling Up to ASEAN 2015: Building Linkages and Securing Chancellor, Ms. Candice Gotianuy, a delegation of more than 73 serve higher educational institutions in the Visayas and Mindanao regions. games and emceed the seminar entitled, “Enabling HEI’s Prepare for Quality Assurance Grants”. -

Region Province Congressional District Name of Institution Type of Institution Classification of Institution Address Tel. No. Se

CONGRESSIONAL TYPE OF CLASSIFICATION OF COURSE/REGISTERED PROGRAM REG. REGION PROVINCE NAME OF INSTITUTION ADDRESS TEL. NO. SECTOR DURATION DATE ISSUED STATUS DISTRICT INSTITUTION INSTITUTION PROGRAM NO. ARMM Maguindanao 1st Illana Bay Integrated Computer College Inc. Private HEI Poblacion 1 Tomawis Bldg. Parang, (+63) 9096953419 Construction Electrical Installation & 402 hours 201615382019 December 9, 2016 WTR Maguindanao Maintenance NC II ARMM Maguindanao 1st Illana Bay Integrated Computer College Inc. Private HEI Poblacion 1 Tomawis Bldg. Parang, (+63) 9096953419 Construction Motorcycle/Small Engine 278 hours 201615382020 December 9, 2016 WTR Maguindanao Servicing NC II ARMM Lanao del Sur 1st Inandang Folklore Promotions Service Private TVI New Capitol Complex, Buadisacayo, None Tourism Bread & Pastry Production 141 hours 201615362021 December 20, 2016 WTR Training and Assessment Centre, Inc. Marawi City, Lanao del Sur NC II ARMM Maguindanao 1st Language Skills Institute - ZCLO Public TESDA Technology 2nd Floor, LHB II Building, Veterans (062)990-2959 ICT Contact Center Services NC 144 hours 201615382013 December 2, 2016 WTR Institution Avenue, Brgy. Zone 3, Zamboanga II City ARMM Tawi-tawi Lone Mahardika Institute of Technology, Inc. Private HEI ILMOH Street, Lamion, Bongao, (068) 268-1259 Electronics Computer Systems 280 hours 201615702014 December 7, 2016 WTR Tawi-Tawi Servicing NC II ARMM Tawi-tawi Lone Mahardika Institute of Technology, Inc. Private HEI ILMOH Street, Lamion, Bongao, (068) 268-1259 Tourism Cookery NC II 316 hours 201615702015 December 7, 2016 WTR Tawi-Tawi ARMM Tawi-tawi Lone Mahardika Institute of Technology, Inc. Private HEI ILMOH Street, Lamion, Bongao, (068) 268-1259 Tourism Food & Beverage Services 356 hours 201615702016 December 7, 2016 WTR Tawi-Tawi NC II ARMM Tawi-tawi Lone Mahardika Institute of Technology, Inc. -

The Philippines Illustrated

The Philippines Illustrated A Visitors Guide & Fact Book By Graham Winter of www.philippineholiday.com Fig.1 & Fig 2. Apulit Island Beach, Palawan All photographs were taken by & are the property of the Author Images of Flower Island, Kubo Sa Dagat, Pandan Island & Fantasy Place supplied courtesy of the owners. CHAPTERS 1) History of The Philippines 2) Fast Facts: Politics & Political Parties Economy Trade & Business General Facts Tourist Information Social Statistics Population & People 3) Guide to the Regions 4) Cities Guide 5) Destinations Guide 6) Guide to The Best Tours 7) Hotels, accommodation & where to stay 8) Philippines Scuba Diving & Snorkelling. PADI Diving Courses 9) Art & Artists, Cultural Life & Museums 10) What to See, What to Do, Festival Calendar Shopping 11) Bars & Restaurants Guide. Filipino Cuisine Guide 12) Getting there & getting around 13) Guide to Girls 14) Scams, Cons & Rip-Offs 15) How to avoid petty crime 16) How to stay healthy. How to stay sane 17) Do’s & Don’ts 18) How to Get a Free Holiday 19) Essential items to bring with you. Advice to British Passport Holders 20) Volcanoes, Earthquakes, Disasters & The Dona Paz Incident 21) Residency, Retirement, Working & Doing Business, Property 22) Terrorism & Crime 23) Links 24) English-Tagalog, Language Guide. Native Languages & #s of speakers 25) Final Thoughts Appendices Listings: a) Govt.Departments. Who runs the country? b) 1630 hotels in the Philippines c) Universities d) Radio Stations e) Bus Companies f) Information on the Philippines Travel Tax g) Ferries information and schedules. Chapter 1) History of The Philippines The inhabitants are thought to have migrated to the Philippines from Borneo, Sumatra & Malaya 30,000 years ago. -

Stella Maris Magazine April 2021 April's Magazine Includes

APRIL 2021 StellaSUPPORTING SEAFARERS AND FISHERSMaris AROUND THE WORLD Port Focus The Good Life Inside Cebu, Philippines Hepatitis A Sunday at Sea Growing in Faith with Fr Pio Idowu Discovering the Paschal Mystery 2 Stella Maris is a Catholic charity supporting seafarers worldwide. We provide practical and pastoral care to all seafarers, regardless of nationality, belief or race. Our port chaplains and volunteer ship visitors welcome seafarers, offer welfare services and advice, practical help, care and friendship. Stella Maris is the largest ship visiting network in the world, working in 332 ports with 227 port chaplains around the world. We also run 53 seafarers’ centres around the world. We are only able to continue our work through the generous donations of our supporters and volunteers. To support Stella Maris with a donation visit www.stellamaris.org.uk/donate Stella Maris 39 Eccleston Square, London, SW1V 1BX, United Kingdom Tel: +44 020 7901 1931 Email: [email protected] facebook.com/StellaMarisOrg www.stellamaris.org.uk Registered charity in England and Wales number 1069833 Registered charity in Scotland number SC043085 Registered company number 3320318 Images Cover, Pg 2 and back cover courtesy of Stella Maris. Pg 8-11 courtesy of istockphoto. Pg 4, 5, 6 and 7 courtesy of Fr Lawrence Lew O.P. DOWNLOAD Stella Maris OUR FREE APP provides seafarers StellaMaris with practical support, information and a listening ear STELLA MARIS MAGAZINE APRIL 2021 PORT FOCUS 3 CEBU, PHILIPPINES The Port of Cebu is located in the 500 thousand seafarers on that was inaugurated on April 29, Cebu City, Philippines. -

'Demonizing' Media

Cebu Journalism & Journalists CJJ12 2017 ‘Demonizing’ media Fake news inflicts more damage in social media Restoring faith in journalism 23+2 / 33 CEBU PRESS Freedom WEEK 25th fete, 33rd year 1984 | Sept. 9-15 1999 | Sept. 19-25 was revived with SunStar as lead managers signed a memorandum The Association of Cebu Journalists, Lead convenor: The Freeman news group. of understanding on valuing public the Cebu Newspaper Workers’ The convenors’ group institutionalized safety in the coverage of crisis Foundation (Cenewof) and Cebu Cebu Press Freedom Week and 2006 | Sept. 17 to 23 situations. A street in Barangay News Correspondents Club organized agreed that each of the three Lead convenor: Cebu Daily News Sambag II, Cebu City was named after the Cebu Press Week celebration newspapers take turns in leading the CJJ2 was launched, and Lens held a sportswriter Manuel N. Oyson Jr. to remind the public and the press activity every year. photo exhibit. SunStar produced the that the freedom it enjoys must be documentary “Killing Journalists.” 2012 | Sept. 15-22 protected from all threats. 2000 | Sept. 17-23 Lead convenor: Cebu Daily News Lead convenor: Cebu Daily News 2007 | Sept. 15-22 Firsts for the celebration included 1988 | Sept. 4-10 The Cebu Federation of Beat Lead convenor: SunStar Cebu the Globe Cebu Media Excellence The Council of Cebu Media Leaders Journalists was organized. SunStar debuted its “Reaching Awards, and the launch of an e-book (CCML)—organized to promote out to future journalists” forum version for the CJJ7 magazine. the development of media as a 2001 | Sept. 16-22 with Masscom students from Cebu profession, upgrade its practice Lead convenor: SunStar Cebu universities. -

Usjr Cebu Courses Offered

Usjr Cebu Courses Offered Pastier and scrumptious Harland becharm almost reshuffling, though Tabbie decussating his ovulation invest. Winnable fanonThatcher focally, itinerating but undistinguishing that waivers teazles Crawford statistically jollify afternoons and apprized or intercut remissly. expectably. Sometimes antidiuretic Redford foregather her Important: Forms that are of less than optimal image quality will not be processed. No community members yet. Basak Campus houses the Recoletos Coliseum and a soccer field. This excavator operator at bauma in Munich, Germany, is actually digging at a jobsite in South Korea. How can it help students prepare better for college? We bring the best content for local destinations, hotels, beaches, restaurants, and foods here in the Philippines. These are popular locations in the selected city, and these will help you make your search easier. Tanong ko lang po f may Divine Mercy Computer College pa ba? Do You Want To. Country mall banilad cebu city and Montebello Hotel. These huge figures seem daunting and the pressure of finding the right school starts to set in. Colegio De San Antonio de Padua has been added to the list. Emilio Osmeña Botanical Garden in Busay! University molded and pushed me to become better than what I thought I could be. Apply online to schools in the Philippines and abroad for free! This information is carefully and constantly monitored for its accuracy by our staff and supporters from our active taxi community. Application process and the cost of tuition. Once your admission record is approved, please proceed with payment. Lopez and Magallanes Sts. Cebu, Philippines taxi rates. -

Professional Regulation Commission Cebu Nurse July 03 - 04, 2021

PROFESSIONAL REGULATION COMMISSION CEBU NURSE JULY 03 - 04, 2021 School : UNIVERSITY OF CEBU - MAIN CAMPUS Address : SANCIANGKO ST. CEBU CITY, CEBU 6000 Building : DON MANUEL GOTIANUY Floor : 2ND Room/Grp No. : 217 Seat Last Name First Name Middle Name School Attended No. 1 ABADINGO AILEEN CELERGIA UNIVERSITY OF CEBU IN LAPULAPU & MANDAUE 2 ABAPO ANJANETTE DUNGOG UNIVERSITY OF CEBU IN LAPULAPU & MANDAUE 3 ABAQUITA FER JOHN GASCON SOUTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY 4 ABAYABAY KRISTA RICA OLAER HOLY NAME UNIVERSITY (for.DIVINE WORD- TAGBILARAN) 5 ABELLA DEXTER MENDOZA UNIVERSITY OF CEBU IN LAPULAPU & MANDAUE 6 ABELLA RUBY PEARL ANTOLIHAO UNIVERSITY OF THE VISAYAS-MANDAUE CITY 7 ABELLERA MERLY MENDOVA UNIVERSITY OF BAGUIO REMINDER: USE SAME NAME IN ALL EXAMINATION FORMS. IF THERE IS AN ERROR IN SPELLING AND OTHER DATA KINDLY REQUEST YOUR ROOM WATCHERS TO CORRECT IT ON THE FIRST DAY OF EXAMINATION. REPORT TO YOUR ROOM ON OR BEFORE 6:30 A.M. LATE EXAMINEES WILL NOT BE ADMITTED. PROFESSIONAL REGULATION COMMISSION CEBU NURSE JULY 03 - 04, 2021 School : UNIVERSITY OF CEBU - MAIN CAMPUS Address : SANCIANGKO ST. CEBU CITY, CEBU 6000 Building : DON MANUEL GOTIANUY Floor : 2ND Room/Grp No. : 218 Seat Last Name First Name Middle Name School Attended No. 1 ABRIGO JOURNALYN FLORES OUR LADY OF FATIMA UNIVERSITY-VALENZUELA 2 ACA-AC NEIL FRANCIS LIGAD SOUTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY 3 ACHAY FRANLE OGAN NORTHERN NEGROS STATE COLLEGE OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY 4 ACIBRON REJELYN CORONADO NEGROS ORIENTAL STATE UNIVERSITY (CVPC)- DUMAGUETE 5 ACUSAR IVY MARIE PEPITO UNIVERSITY OF SAN CARLOS 6 ADANZA RIZZA BILORIO NEGROS ORIENTAL STATE UNIVERSITY (CVPC)- DUMAGUETE 7 AGBAY CAROLINE HANNAH PECHO UNIVERSITY OF THE VISAYAS-CEBU CITY REMINDER: USE SAME NAME IN ALL EXAMINATION FORMS. -

230 Ict Skills Enhancement Training in Teacher

ISSN Online: 2076-8184. Information Technologies and Learning Tools, 2014, Vol 39, №1. Dave E. Marcial Assistant Professor, Ph.D. in Education, Coordinator for Silliman Online University Learning College of Computer Studies, Silliman University, Dumaguete City, Negros Oriental, Philippines [email protected] Mitzi S. Fortich Area Coordinator, Master in Business Administration, SU-PHERNet Project 6 Silliman University, Dumaguete City, Negros Oriental, Philippines [email protected] Jeambe B. Rendal Project Staff, Bachelor of Science in Information Technology, SU-PHERNet Project 6 Silliman University, Dumaguete City, Negros Oriental, Philippines [email protected] ICT SKILLS ENHANCEMENT TRAINING IN TEACHER EDUCATION: THE CASE IN CENTRAL VISAYAS, PHILIPPINES Abstract . There are many evidence that the use of information and communication technology (ICT) in education provides effective pedagogical benefits. This paper describes the ICT skills enhancement training among faculty members in the teacher education in the four provinces, in Central Visayas, Philippines. The technology literacy training was designed for teacher educators who have the minimal or no knowledge or who have the ability to explain and discuss the task, but have not experienced the actual process of ICT operations in the classroom. It aimed to enhance skills in ICT operations and concepts using international and local ICT competency standards for teacher education. A total of 60 trainees who are coming from 30 private and public higher education institutions in the region participated in the training. The success level of the training program was measured in terms of the effectiveness of the trainers, learning level acquired by trainees, effectiveness of the administration of the training, relevance of the topic, and adequacy of information shared by the trainers. -

Rizal Commercial Banking Corporation Operational Atms As of 06 Aug 2020 Subject to Change Without Prior Notice

Rizal Commercial Banking Corporation Operational ATMs as of 06 Aug 2020 Subject to change without prior notice ATM Name City/Province Address Butuan 2 Agusan Del Norte Cor. E. Luna And Lopez Jaena Sts., Butuan City Butuan 3 Agusan Del Norte Fsuu Cbe Ester Luna St. Butuan City Butuan-Libertad Agusan Del Norte R.T Bldg. J.C Aquino Ave., Libertad, Butuan City Beach Front Station 1 Aklan Boracay Realty, Beach Front, Station 1, Brgy. Balabag, Boracay Island, Malay Aklan Boracay Aklan Station 1, Brgy. Balabag, Boracay Island, Malay, Aklan City Mall Kalibo Aklan 19 Martyrs Street, Kalibo, Aklan Citymall Boracay Aklan Brgy. Balabag Malay, Buruanga City, Aklan Kalibo, Aklan Aklan Roxas Ave., Kalibo, Aklan Aquinas University Hospital Albay F. Aquende Drive,Legaspi City Lcc Mall Tabaco Albay Ziga Avenue,Tabaco City Legazpi City Albay M. Dy Bldg., Rizal St., Legaspi City Legazpi-Landco Business Park Albay G/F Delos Santos Commercial Bldg. Landco Business Park Legazpi City, Albay Mariners Polytechnic Colleges Albay Mariners Polytechnic Colleges Foundation, Rawis, Legaspi City, Albay Pacific Mall Legazpi Albay Landco Business Park, F. Imperial St., Cor. Circumferential Rd. Legazpi City Tabaco Albay 232 Ziga Ave., Tabaco City, Albay Antique 2 Antique Solana Cor. T.A. Fornier Sts., San Jose, Antique San Jose Antique Antique Solana Cor. T.A. Fornier Sts., San Jose, Antique San Jose Multi-Purpose Cooperative Antique Antique Trade Town Dalipe, San Jose, Antique Baler, Aurora Aurora Quezon Ave. Cor. Bonifacio St. Baler, Aurora Province Balanga Bataan Don Manuel Banzon Avenue Cor. Cuaderno Street, Doña Francisca Subdivision, Balanga City, Bataan Balanga 2 Bataan Don Manuel Banzon Avenue Cor.