The Normal Lights Philippine Normal University Journal on Teacher Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PS Rbs CPU Directory for Website February 2021.Xlsx

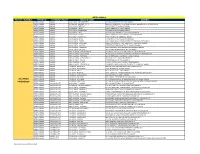

METRO MANILA PAYOUT CHANNELS PROVINCE CITY/MUNICIPALITY BRANCH NAME ADDRESS METRO MANILA MANILA H VILLARICA - BLUMENTRITT 1 1714 BLUMENTRITT ST. STA CRUZ MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA H VILLARICA - BLUMENTRITT 2 1601 COR. BLUEMNTRITT ST & RIZAL AVE BRGY 363,ZONE 037 STA CRUZ MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA H VILLARICA - BUSTILLOS 443 FIGUERAS ST. SAMPALOC MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA H VILLARICA - PACO 1 # 1122 PEDRO GIL ST., PACO MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA H VILLARICA - PADRE RADA 656 PADRE RADA ST TONDO MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA H VILLARICA - PRITIL 1 1835 NICOLAS ZAMORA ST TONDO BGY 86 MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA H VILLARICA - QUINTA 200 VILLALOBOS ST COR C PALANCA ST QUIAPO MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA H VILLARICA - SAMPALOC 1 1706 J. FAJARDO ST. SAMPALOC MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA HL VILLARICA - D JOSE 1574 D.JOSE ST STA. CRUZ NORTH,MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA HL VILLARICA - ESPAÑA 1664 ESPANA BLVD COR MA CRISTINA ST SAMPALOC EAST,MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA HL VILLARICA - LAON LAAN 1285 E. LAON LAAN ST., COR. MACEDA ST., SAMPALOC MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA HL VILLARICA - MACEDA 1758 RETIRO CORNER MACEDA ST. SAMPALOC MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA HL VILLARICA - PANDACAN 1922 J ZAMORA ST BRGY 851 ZONE 93 PANDACAN MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA HL VILLARICA - STA. ANA 1 3421-25 NEW PANADEROS ST. STA.ANA MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA HRV VILLARICA - ERMITA MANILA UYGUANGCO RD., BO. STO. NIÑO BRGY 187 TALA CALOOCAN METRO MANILA MANILA HRV VILLARICA - GAGALANGIN 2710 JUAN LUNA ST GAGALANGIN BRGY 185 ZONE 016 TONDO MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA HRV VILLARICA - HERMOSA 1157 B. HERMOSA ST. MANUGUIT TONDO MANILA METRO MANILA MANILA HRV VILLARICA - ILAYA MANILA #33 ARANETA ST. -

Cebu 1(Mun to City)

TABLE OF CONTENTS Map of Cebu Province i Map of Cebu City ii - iii Map of Mactan Island iv Map of Cebu v A. Overview I. Brief History................................................................... 1 - 2 II. Geography...................................................................... 3 III. Topography..................................................................... 3 IV. Climate........................................................................... 3 V. Population....................................................................... 3 VI. Dialect............................................................................. 4 VII. Political Subdivision: Cebu Province........................................................... 4 - 8 Cebu City ................................................................. 8 - 9 Bogo City.................................................................. 9 - 10 Carcar City............................................................... 10 - 11 Danao City................................................................ 11 - 12 Lapu-lapu City........................................................... 13 - 14 Mandaue City............................................................ 14 - 15 City of Naga............................................................. 15 Talisay City............................................................... 16 Toledo City................................................................. 16 - 17 B. Tourist Attractions I. Historical........................................................................ -

The Beacon Academy Faculty List Ay 2020-2021 1

THE BEACON ACADEMY FACULTY LIST AY 2020-2021 1. Mark Vincent Escaler Head of School MA Individualized Study – focus on Postmodern Philosophy & Film/Media Studies (Gallatin School of Individualized Study – New York University) 2. Maria Elena Paterno-Locsin Dean of Faculty & Acting Diploma Program/ Diploma Programme Senior High School Coordinator IB MYP School Visit Team Member Master of Education (Harvard University) DP English 3. Maria Teresa Roxas Dean of Students BA Anthropology (University of The Philippines) MYP Comparative Religion 4. Roy Aldrin Villegas Middle Years Program/Junior High School Coordinator BS Secondary Education (De La Salle University) MYP Biology, MYP Physics ---- 5. Natalie Albelar Guidance Counselor MA Counselling (De La Salle University) 6. Amor Andal Learning Support and Development Bachelor in Elementary Education, Major in Special Education (University of the Philippines) 7. Jose Badelles Arts Director AB Psychology (Ateneo De Manila University) DP Visual Arts THE BEACON ACADEMY FACULTY LIST AY 2020-2021 8. LeaH Joy Cabanban MA Education/ MA Business Management (University of the Philippines) DP Business and Management 9. Alfred Rey Capiral Fine Arts, Major in Painting (University of the Philippines) MYP Design, MYP Visual Arts 10. Helena Denise Clement College Counselor, Junior High School Bachelor of Business Administration (Loyola Marymount University) 11. Maria Celeste Coscolluela MA Creative Writing (University of the Philippines) DP English 12. Ana Maria David IB Examiner- Math Studies BS Industrial Engineering (Adamson University) DP Mathematics/Math Learning Support Teacher 13. Vian Claire Erasmo Guidance Counselor, Senior High School MA Counselling (Miriam College) 14. Ma. Concepcion Estacio Athletics Director B Communication Media Production (Assumption College) 15. -

Graduate Student Handbook

STUDENT HANDBOOK STUDENT HANDBOOK 2015 - 2018 2015-2018 The Student Handbook Revision Committee AY 2015-2018 Name: Name: Chairperson Ms. Fritzie Ian Paz-De Vera Dean of Student Affairs Address: Address: Members Dr. Rosemary Seva Telephone: I.D Number: Dean, Gokongwei College of Engineering Email Address: Email Address: Dr. Rochelle Irene Lucas Vice Dean, Br. Andrew Gonzalez FSC College of Education Course: Course: Ms. Elsie Velasco Faculty, Accountancy Department Mr. Oscar Unas Faculty, Manufacturing Engineering and Management Department Carlo Iñigo Inocencio President, University Student Government FOREWORD Wilbur Omar Chua Chairperson, Council of Student Organizations Jose Mari Carpena The regulations that appear on this Student Handbook apply to all undergraduate Graduate Student Council Convenor and graduate students who are enrolled in the different colleges of the University. GSC President, CLA Upon admission, they agree to abide by these regulations so as to maintain Consultant Atty. Christopher Cruz discipline, uphold the good order of the school, preserve the fair name of the University Legal Counsel University, and actualize its Mission-Vision Statement. Secretariat Ms. Maria Cecilia Renee Moreno Aside from norms contained in this Student Handbook, bulletin board and website postings, special manuals for specific purposes, and published announcements Resource Persons Joy Fajardo are the ordinary channels by which the University administration informs the student President, DLSU Parents of University Students Organization body of official business. The students should consult these channels regularly. Dr. Voltaire Mistades University Registrar The administrative authority of the University is vested on the President of the institution. The continued attendance of any student at De La Salle University Ms. -

Mary Aim to Streamline R&E Operations

bsu.edu.ph Benguet State University @BenguetStateU @benguetstateuniversityofficial Benguet State University BSU Research and Extension Coordinators from the different colleges, full time researchers and staff of R&E Sector gathered in iNSIDE a 5-day Planning Workshop in Dagupan City with the primary aim to streamline R&E operations. //NLenguaje pAGE 6 pAGE NSTP conducts singing competition and eco-fashion show to promote environmental conservation pAGE 4 pAGE Faculty and students train on fruit and vegetable carving Official Publication of Benguet State University pAGE 7 pAGE BSU conducts training on PAP proposal preparation with ShamagISSN 0118-0304 MARCH 2019 gender perspective Vol. XXVIV No. 3 Workshop held to align R&E operations with Sustainable Development Goals The BSU Research and Extension sector conducted a planning-workshop to streamline research and extension operations on March 25-29, 2019 at Dagupan TBI Project Leaders City, Pangasinan. Dr. Carlito P. Laurean, Vice President faculty from the Colleges as pool of researchers urged to ‘level up’ for Research and Extension, said that the in the various R & E Centers; and identify planning-workshop intends to identify RDE agenda and priorities aligned with the overlaps and interfaces between and among the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as R & E centers; mainstream student researches well as to map out the 3-year operational plan into the University R & E programs; identify (2020-2022) of the sector. CONTINUED ON PAGE 5 “There must be a leveling up in your TBI (Technology Business Incubation).” Mr. Noel A. Catibog of DOST- BSU student makes it to 21st Ayala Young PCAARRD said to batch 2 project leaders of the TBI program during Leaders Congress the Agribusiness Incubation rd Cristine M. -

Assumption University Martin De Tours School of Management and Economics Department of Marketing Full-Time Lecturers' Profile

Assumption University Martin de Tours School of Management and Economics Department of Marketing Full-time Lecturers' Profile CODE NO PHOTOGRAPH NAME SURNAME ACADEMIC QUALIFICATION CONTACT OFFICE POSITION/RESPONSIBLE UNITS Office; Huamak: D6 DBA, University of South Australia, Australia Room 3 CHAIRPERSON 400192 DR. SUWANNA KOWATHANAKUL MBA, Shenshuu University, Tokyo, Japan Bangna: MSM Bldg. BBA, Assumption University, Thailand 2 Floor. Ph.D. Candidate, Assumption University Office; Bangna: DEPUTY CHAIRPERSON 400174 MS. PUNNALUCK SATANASAVAPAK MSc International Business, South Bank MSM Bldg. 3 Floor. University,London, UK BBA, Assumption University, Thailand Ph.D., Adamson University, Philippines Office; Huamak: D6 300005 DR. YOKFAR PHUNGPHOL MBA, Texas University, US Office Bangna: ADVISING BBA, Assumption University, Thailand MSM Bldg. 2 Floor. Assumption University Martin de Tours School of Management and Economics Department of Marketing Full-time Lecturers' Profile CODE NO PHOTOGRAPH NAME SURNAME ACADEMIC QUALIFICATION CONTACT OFFICE POSITION/RESPONSIBLE UNITS 380040 DR. THEINGI Ph.D., University of Western Australia, Perth Office; Bangna: RESEARCH & CASES STUDY MBA, Assumption University, Thailand MSM Bldg. 3 Floor. BBA, Assumption University, Thailand 410133 Ph.D., Kent State University, USA Office; Bangna: ACTING DEPUTY CHAIRPERSON ASST.PROF.DR.VIKANDA PORNSAKULVANICH MA, University of Dayton, USA MSM Bldg. 3 Floor. RESEARCH & CASES STUDY BA, Thammasat University, Thailand 500035 MR. NITIPAN RATANASAWETWAD Ph.D. Candidate, University -

2019 Annual Report

BENGUET S T AT E U NIVERSI T Y 2019 ANNUAL REPORT ACADEMIC SECTOR 2019 ANNUAL REPORT: ACADEMIC SECTOR 2019 Table of Contents I. CURRICULUM AND INSTRUCTION .......................................................................................................... 3 A. Degree Programs and Short Courses ........................................................................................ 3 B. Program Accreditation .............................................................................................................. 6 C. Program Certification ................................................................................................................ 9 II. STUDENTS ............................................................................................................................................ 10 A. Enrolment ................................................................................................................................ 10 B. Student Awards ....................................................................................................................... 17 C. Student Scholarship and RA 10931 Implementation .............................................................. 19 D. Student Development ............................................................................................................. 20 E. Student Mobility ...................................................................................................................... 21 F. Graduates ............................................................................................................................... -

Internationalization of Teacher Education in the Philippines: Innovative Practices That Made a Difference

PATEF Conference 2010 November 27, 2010 Bayview Park Hotel INTERNATIONALIZATION OF TEACHER EDUCATION IN THE PHILIPPINES: INNOVATIVE PRACTICES THAT MADE A DIFFERENCE Rene C. Romero Vice President, UNESCO-APNIEVE Philippines Philippine Normal University WHAT MAKES A UNIVERSITY INTERNATIONAL? “it is the presence of a clear institution-wide positive attitude toward understanding better other cultures and societies, learning more about the political and economic interconnectedness of humankind, a genuine interest in interacting with representatives of these other cultures and societies, a genuine desire to understand the major issues confronting the human and ecological survival of planet earth and to learn how to cooperate with others across national and cultural boundaries in seeking solutions to world problems, irrespective of one’s own academic course of studies, career, profession or station in life. Where such a positive international institutional attitude exists, it inevitably translates itself gradually in the curriculum and the overall university ‘international/intercultural ethos.” Maurice Harari (1997) International Association of University Presidents “ Internationalization of higher education is the process of integrating an international/intercultural dimension into the teaching, research and service functions of the institution.” Jane Knight (1999) The main purpose of the internationalization of higher education is: “ to produce graduates who have the ability to be an active part in a globalized society, able to communicate -

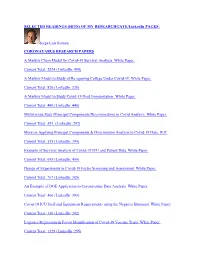

SELECTED READINGS (HITS) of MY RESEARCHGATE/Linkedin PAGES

SELECTED READINGS (HITS) OF MY RESEARCHGATE/LinkedIn PAGES: Jorge Luis Romeu CORONAVARUS RESEARCH PAPERS A Markov Chain Model for Covid-19 Survival Analysis. White Paper. Current Total: 2024 (LinkedIn: 490) A Markov Model to Study of Re-opening College Under Covid-19. White Paper. Current Total: 826 (LinkedIn: 320) A Markov Model to Study Covid-19 Herd Immunization. White Paper. Current Total: 490 (LinkedIn: 440) Multivariate Stats (Principal Components/Discrimination) in Covid Analysis. White Paper. Current Total: 591 (LinkedIn: 297) More on Applying Principal Components & Discrimation Analysis to Covid-19 Data. W.P. Current Total: 535 (LinkedIn: 394) Example of Survival Analysis of Covid-19 ICU and Patient Data. White Paper. Current Total: 693 (LinkedIn: 409) Design of Experiments in Covid-19 Factor Screening and Assessment. White Paper. Current Total: 767 (LinkedIn: 305) An Example of DOE Application to Coronavarius Data Analysis. White Paper. Current Total: 406 (LinkedIn: 393) Covid-19 ICU Staff and Equipment Requirements using the Negative Binomial. White Paper. Current Total: 336 (LinkedIn: 202) Logistics Regression in Factor Identification of Covid-19 Vaccine Trials. White Paper. Current Total: 1328 (LinkedIn: 255) Survival Analysis Applied to Establishing Covid-19 Vaccine Life Length. White Paper. Current Total: 540 (LinkedIn: 341) Some Statistical Methods to Accelerate Covid-19 Vaccine Testing Current Total: 1064 (LinkedIn: 220) A Markov Model to Assess Covid-19 Vaccine Herd Immunization Patterns. White Paper. Current Total: 585 (LinkedIn:253) Design and Operation of an ICU Using Reliability Principles. White Paper. Current Total: 167 (LinkedIn: 266) Commented Summary of a Year of Work in Covid-19 Statistical Modeling. -

Profile of the Board of Directors

PROFILE OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS Atty. Baldomero C. Estenzo DIRECTOR Age: 76 Academic Qualification: Graduate from the University of San Carlos in Cebu City in 1963 with a degree of Bachelor of Science in Commerce major in Accounting. Graduate from the University of the Philippines in 1968 with a degree of Bachelor of Laws. Ranked No. 5 in the list of graduating students from the College of Law. Experience: 1965‐1969‐ Auditing Aide & Reviewer Bureau of Internal Revenue Department of Finance, Manila 1969‐1979 Practicing Lawyer in Cebu Commercial Law Lecturer Cebu Central Colleges 1979‐1990 Head of Legal Unit of San Miguel Corporation, Mandaue City 1990‐2004 Assistant Vice President & Deputy Gen. Counsel of San Miguel Corporation 2006 Vice President & Deputy General Counsel of San Miguel Corporation 2007‐Present Executive Vice Chancellor & Dean, College of Law of the University of Cebu Ms. Candice G. Gotianuy DIRECTOR Age: 46 Academic Qualification: AB in Political Science, Ateneo de Manila University Masters in Education, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA Experience: President, University of Cebu Medical Center Managing Director, St. Vincent’s General Hospital President, College of Technological Sciences Chancellor, University of Cebu ‐ Banilad Campus ‐ Main Campus ‐ Maritime Education & Training Center ‐ Lapu‐lapu and Mandaue Campus Treasurer, Chelsea Land Development Corporation Vice‐President, Gotianuy Realty Corporation Director, Cebu Central Realty Corporation (E‐Mall) Director, Visayan Surety & Insurance Corporation Director, -

PACU Newsletter Opportunities”

Summer Fellowship at the Bayleaf PACU continues the "Summer Fellowship" pioneered by immediate past president Peter P. Laurel.At this event, PACU members come together to bond, enjoy, dine and dance just for an evening away from the rigors of the administrative and academic grind. PACU At The Forefront Of Academic And Educational Updates PACU: Reaching out... (cover story) We were all happy that Ushering academic year 2012- 2013, the PACU program committee facilitated and conducted three academic management seminars at Sun Life Financials, proposed interesting possibilities on attended and participated on January 24- 25, 2013. Aptly titled Dr. Butchie Lim Ayuyao graced the occasion. in different regions of the country : National Capital Region, Quezon Province, Luzon and Cebu City, for the PACU members in the “Establishing and Maintaining School Endowments and Grants”. “Preparing HEI’s for the Challenges Ahead: Addressing regions of Visayas and Mindanao. Concerns on K-12, ASEAN 2015 and Quality Assurance”, the Our thanks reach out to The third academic management seminar was conducted seminar delivered timely updates on current critical concerns. Dr. Gerry Cao who TIP Chairman, Dr. Tessie Quirino and TIP President Beth Enverga University Foundation hosted the seminar entitled at the University of Cebu, Banilad Campus. Welcomed by the Although open to all interested parties, the seminar was meant to gamely hosted the Lahoz welcomed PACU and over 172 participants in the first “Leveling Up to ASEAN 2015: Building Linkages and Securing Chancellor, Ms. Candice Gotianuy, a delegation of more than 73 serve higher educational institutions in the Visayas and Mindanao regions. games and emceed the seminar entitled, “Enabling HEI’s Prepare for Quality Assurance Grants”. -

DLSU Launches Global Standard Sustainability Report

THE OFFICIAL NEWSLETTER OF DE LA SALLE UNIVERSITY Volume 52 • Number 06 • 29 January 2021 DLSU launches global standard Sustainability Report In pursuit of its commitment to sustainability, De La Salle What’s inside University recently released its first Sustainability Report, International educators share 2 which conforms to the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). HEI experiences in the new normal GRI is one of the internationally accepted standards to determine how an organization tackles sustainability New lab acquires cutting-edge 3 equipment for tissue engineering issues, including impacts and risks. Communication students 4 receive award in business innovation challenge Continue on Page 2 Global Grad Show 2020 5 DLSU launches global standard Sustainability Report, From Page 1 A non-profit organization that is not covered by the Securities CSO added that with the report, the University aims to move and Exchange Commission requirement to submit a Sustainability forward towards becoming a cleaner and greener university, Report annually, DLSU still took the initiative to produce the report, with programs and policies geared towards the attainment in line with its vision-mission as a leading learner-centered and of this goal. research University that is “attuned to a sustainable Earth.” The report includes messages from President Br. Raymundo The Sustainability Report covers the period 2017-2019. Suplido FSC and Chancellor Br. Bernard Oca FSC as well as Highlighting the transparent, accurate, authentic, and thorough DLSU’s Sustainability Policy and Agenda, Carbon Neutrality features of the report, the Campus Sustainability Office (CSO) Project, best practices, and curriculum and research promoting said it will have succeeding editions every two years.