The Jewish View of Ecology and the Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parshat Ki Tetze the 5770-5771 Year Begins

newsletter In This Issue Parshat Ki Tetze HaRav Nebenzahl on Parshat Ki Tetze The 5770-5771 Year Begins Kollel Rennert Dvar Torah by HaRav Aharon Amar There is excitement in the air as Netiv Aryeh welcomes Staff Dvar Torah by Rav the return of Shana Bet students whose first official day Zvi Ron of Yeshiva was Wednesday 8 Elul. We are looking forward Visitor Log, Mazal Tov's, to welcoming Shana Alef this coming Tuesday. This year Tehillim List the Yeshiva will be learning Massechet Baba Batra. We pray for Siyata D'Shmaya in helping all our students grow Join our list in Torah and Yirat Shamayim. Join our mailing list! RBS Shabbaton! Join Attention alumni and friends living in Ramat Beit Shemesh!!! We are proud to announce that the Rosh Yeshiva HaRav Aharon Bina, HaRav Amos Luban, and HaRav Yitzchak Korn will be joining us for an Alumni Shabbaton in RBS! This may be a once in a lifetime experience so be sure not to miss out! Reserve the date: 25th of Elul, Shabbat Parshat Nitzavim Vayelech (September 3rd-4th) Stay tuned for final details on this amazing Shabbat experience!... YNA.EDU | Ask Rav Nebenzahl | Suggestion Box Contact | Alumni Update | Parsha Us Form Archives American Friends of Netiv Aryeh supports our programs. To contribute to American Friends of Netiv Aryeh, please visit http://www.afna.us/donate HaRav Nebenzahl on Parshat Shoftim HaRav Nebenzahl asks that his Divrei Torah are not read during Tefillah or the Rabbi's sermon 1 of 14 newsletter "Ani LeDodi veDodi Li" Chazal allowed themselves to begin Torah discussions on a humorous note (see Shabbat 30b), let us do so as well. -

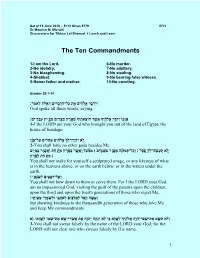

The Ten Commandments

Sat 8+15 June 2019 – 5+12 Sivan 5779 B”H Dr Maurice M. Mizrahi Discussions for Tikkun Lel Shavuot + Lunch and Learn The Ten Commandments 1-I am the Lord. 6-No murder. 2-No idolatry. 7-No adultery. 3-No blaspheming. 8-No stealing. 4-Shabbat. 9-No bearing false witness. 5-Honor father and mother. 10-No coveting. Exodus 20:1-14 וַיְדַבֵֵּ֣ר אֱֹלה ִ֔ ים תאֵֵ֛ כָּל־הַדְ בָּר ִ֥ יםהָּאֵֵ֖ לֶּה לֵאמ ֹֽ ר׃ God spoke all these words, saying: אָֹּֽנכֵ֖י֙יְהוֵָּּ֣האֱֹלהֶּ ִ֔ יָךאֲשֶֶּׁ֧ רהֹוצֵ את ֵ֛ יָך ץ מֵאִֶּ֥רֶּ מ צְרֵַ֖ ים מבֵֵּ֣ ִֵּ֥֥֣ית עֲבָּד ֵֹּֽ֥֣ים׃ 1-I the LORD am your God who brought you out of the land of Egypt, the house of bondage: ֵּ֣ ֹֽל א י ְה ֶֹּֽיה־ ְל ֵ֛ ָָ֛֩ך ֱאֹל ִִ֥֥֨הים ֲא ֵ חִֵ֖֖֜רים ַעל־ ָּפ ָָֹּֽֽ֗נ ַי 2-You shall have no other gods besides Me. ֵּ֣ ֹֽל א ֹֽ ַת ֲע ִ֥֨ ֶּשה־ ְל ִָ֥ךֵּ֣ ֵֶּּ֣֙פ ֶּס ֙ל ׀ ְו ָּכל־ ְתמ ּו ִָּ֔נה ֲא ֶּ ֵּ֣שֵּ֥֣ר ַב ָּש ֵַּ֣֙מ י ֙ם ׀ מ ִַ֔מ ַעל ֹֽ ַו ֲא ִֶּ֥ש ָ֛֩ר ָּב ִֵָּ֥֖֨א ֶּרץ מִָּ֖֜ תֵַּ֥֣ ַחת וַאֲשִֶּ֥ ֵֵּּ֣֥֣רבַמֵַ֖ ֵֵּּ֣֥֣ים ׀מתִַ֥ ֵֵּּ֣֥֣חַת לָּאָָֹּֽֽ֗רֶּ ץ You shall not make for yourself a sculptured image, or any likeness of what is in the heavens above, or on the earth below, or in the waters under the earth. וְעַל־רבֵע ֵ֖ ים לְ ש נְאָּ ֵֹּֽ֥֣י׃ You shall not bow down to them or serve them. For I the LORD your God am an impassioned God, visiting the guilt of the parents upon the children, upon the third and upon the fourth generations of those who reject Me, וְעִ֥ שֶּה חֵֶּ֖֙סֶּד֙ לַאֲלָּפ יםִ֔ לְא הֲבֵַ֖י ּולְש מְרִֵ֥ י מצְ ו תָֹּֽ י׃ but showing kindness to the thousandth generation of those who love Me and keep My commandments. -

Vol. 8 #29, May 7, 2021; Behar Bechukotai 5781; Shabbat Mevarchim

BS”D May 7, 2021 25 Iyar5781 Friday is the 40rd day of the Omer, Lag B’Omerr Potomac Torah Study Center Vol. 8 #29, May 7, 2021; Behar Bechukotai 5781; Shabbat Mevarchim NOTE: Devrei Torah presented weekly in Loving Memory of Rabbi Leonard S. Cahan z”l, Rabbi Emeritus of Congregation Har Shalom, who started me on my road to learning 50 years ago and was our family Rebbe and close friend until his recent untimely death. ____________________________________________________________________________________ Devrei Torah are now Available for Download (normally by noon on Fridays) from www.PotomacTorah.org. Thanks to Bill Landau for hosting the Devrei Torah. ______________________________________________________________________________ With so much going on in the world, leave it to me to miss an important anniversary. Last Sunday, 20 Iyar, was the 3332nd anniversary of our ancestors leaving their camp at the base of Har Sinai to continue their journey from Egypt to Israel (Bamidbar 10:11). We shall read what happened in three weeks (sixth aliyah). This Shabbat, however, we complete Sefer Vayikra, the middle section of the Torah, whose main focus is the conditions required to live in close proximity to our Creator. Behar presents the mitzvot of shemittah and yovel. When the Jews enter the land that God promised to their ancestors, the land is to observe Shabbat in a way similar to the way that we observe Shabbat – by resting from productive activity. Every seventh year, the land of Israel is to rest – no planting, tilling, or working the ground. Should the land produce crops on its own, any person who wishes may take the produce – whatever the land generates is kefker (ownerless and thus available on a first come/first served basis). -

By Bruce Roth

TOWSON UNIVERSITY OFFICE OF GRADUATE STUDIES ANALYSIS OF THE RABBINIC USAGE OF “BECAUSE OF THE WAYS OF PEACE” by Bruce Roth A Thesis Presented to the faculty of Towson University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Department of Jewish Studies Towson University Towson, Maryland 21252 December 2014 II Acknowledgements I would like to express gratitude and acknowledgement to my advisor Dr. Avram Reisner. Many people helped, but special mention is due to Zvi Leshem from the National Library of Israel for helping me with data searches, to Chava and Zach my children, and to my beloved wife Rachel for all their encouragement. III Abstract Rabbinic Literature highlights the pursuit of a peaceful and just society. This paper argues that contemporary modes of discourse have utility in understanding the social problems that the Rabbis sought to solve. By reading and interpreting a specific rabbinic decree justified as Mipnai Darchei Shalom “because of the ways of peace” (MDS), this paper demonstrates that the understanding of specific rabbinic laws can be enhanced by using contemporary terms such as “groups”, “power” and contemporary definitions such as “human, cultural and individual values”. The desire to minimize and resolve social conflict sheds light on the sages pursuing an ordered society, much as society aspires to do today. IV CONTENTS INTRODUCTION.………………………………………………………………………..1 CHAPTER ONE: Readings…..……………………………………………………………………….5 Mishnah…………………………………………………………………………....6 Tosefta……………………………………………………………………………13 -

Rabbi Melman’S Office Hours at Temple Israel of the Poconos

Page TEMPLE ISRAEL OF THE POCONOS Edition 657 Temple Israel of Drawing by Marilyn Margolies the Poconos July 2019 Sivan/Tammuz 5779 Edition 657 A monthly publication of Temple Israel of the Poconos Inside this Issue BREACHING THE WALLS (and connecting with others) Rabbi’s Message 1 © 2019 by Rabbi Baruch Binyamin Hakohen Melman Directory 2 President’s Message 3 I am fully aware that even fasting on Yom Kippur is a challenge for many! But our only "holiday" this month marks the observance Hebrew School 4 of the Fast of Tammuz, falling this year on Sunday, July 21, corre- Ask the Rabbi 5-6 sponding to the 17th of Tammuz, hence its official name, Taanit Rabbi’s Hours 6 Shivah Assar baTammuz, meaning the Fast of the 17th of Tammuz. Hevra Kadisha 7 This fast day begins the semi-mourning period called The Three Weeks, culminating on the tragic fast day known as Tisha B'Av. As High Holiday Booklet 7 Jews we mark these special occasions not only because they link us Members Messages 8 to the historical events of our ancient people's history but also be- Dance Class 9 cause they add meaning to our modern lives, infusing them with deeper spiritual significance. While the world enjoys its summer Donations 10 festivities, alas, we conspire to delve and reflect inward! Yarzheits 11 So why do we observe the 17th of Tammuz? Several reasons are Rabbi’s Classes 12 given in the Talmud, but I will choose to focus on just two, for the Birthdays/Anniversaries 13 sake of brevity. -

Tzurba M'rabanan Learning Program Now in English!

JOIN THE REVOLUTIONARY TZURBA M'RABANAN LEARNING PROGRAM NOW IN ENGLISH! OVER 20,000 LEARNERS IN HUNDREDS OF COMMUNITIES ALL OVER THE WORLD A systematic and concise Clear and concise learning method, from introductions and the Talmudic source a modern English through modern-day translation alongside the halachic application original Hebrew text Cover 300 major topics Color-coded sections, in Shulchan Aruch, icons and elucidation learning once a week to guide the learner, in during a four-year cycle addition to in-depth essays and responsa to complement the learning Tzurba M'Rabanan is available as a podcast on all major platforms, including iTunes, Spotify and Google VISIT WWW.TZURBAOLAMI.COM TO ORDER BOOKS OR TO FIND A LOCAL SHIUR LEARNING SCHEDULE FOR THE TZURBA M'RABANAN ENGLISH EDITION YEAR ONE YEAR TWO FEBRUARY–DECEMBER 2019 DECEMBER 2019–AUGUST 2020 VOLUME 1 KASHRUT (18 shiurim) Shiur 1 AVODA ZARA 1 February 2 TAHARAT HAMISHPACHA (11 shiurim) Shiur 2 AVODA ZARA 2 February 9 ORACH CHAIM Shiur 3 CHUKOT HAGOYIM February 16 HALACHOT ON WAKING UP IN THE MORNING (2 shiurim) TZITZIT (5 shiurim) Shiur 4 MAGIC AND SORCERY February 23 TEFILLIN (4 shiurim) Shiur 5 PEOT HAROSH March 2 TEFILLA/MINYAN/HALACHIC TIMES (6 shiurim) Shiur 6 PEOT HAZAKAN March 9 Shiur 7 PURIM March 16 YEAR THREE PURIM BREAK SEPTEMBER 2020–AUGUST 2021 Shiur 8 SHILUACH HAKEN March 30 Shiur 9 SEDER NIGHT 1 April 6 TEFILLA (12 shiurim) Shiur 10 SEDER NIGHT 2 April 13 NETILAT YADAYIM (3 shiurim) PESACH BREAK BRACHOT ON FOODS, SHEHECHIYANU, HAGOMEL, ETC. (12 shiurim) MITZVOT -

PARSHAT KI TETZEI 8:15 A.M., Parsha Shiur

“ SHABBAT MORNING SERVICES 7:00 a.m. Shacharit Minyan, Main Sanctuary 8:00 a.m. Shacharit Minyan, Upstairs Rooms 1 & 2 8:45 a.m. Sephardic Minyan, Library 8:45 a.m. Minyan, House across the street 9:00 a.m. Shacharit Minyan, Main Sanctuary. Please note: The Rabbi’s sermon and the D’var Torah from the Bar Mitzvah boy, YOUNG ISRAEL OF HOLLYWOOD-FT. LAUDERDALE David Leubitz, will be after Mussaf before Ein Keilokeinu. 9:30 a.m. YP Minyan, Chapel Rabbi Yosef Weinstock 9:00 a.m. Youth Minyan, this week will join the Leubitz Bar Mitzvah in the Main Rabbi Edward Davis, Rabbi Emeritus Sanctuary Dr. P.J. Goldberg, President 9:30 a.m. Teen Minyan, Upstairs Room 5 3291 Stirling Road, Ft. Lauderdale, FL 33312 954-966-7877 email: [email protected] www.yih.org - For Weekday Daily Minyanim see Page 6- SHABBAT SHALOM. WE WELCOME ALL NEWCOMERS, VISITORS AND GUESTS JOINING US FOR SHABBAT. SHABBAT SCHEDULE OF CLASSES PARSHAT KI TETZEI 8:15 a.m., Parsha Shiur. 9:10 a.m. Chapel: Sefer HaChinuch Shiur, Rabbi Raphael Stohl, preceding 9:30 11 ELUL 5777 SEPTEMBER 2, 2017 TORAH READING Deuteronomy 21:10 a.m. YP Minyan. HAFTORAH Isaiah 54:1 Parsha classes with Rabbi Yitzchak Salid: 9:15 a.m. in Rm. 6, 10:15 a.m. in Nach Yomi : Ecclesiastes 6 Kiddush room in house across the street (access through glass door on north side of house). Daf Yomi : Sanhedrin 48 After 8:00 a.m. Minyan, Social Hall: The Rest of the Story: Understanding the Haftarah, Rabbi Yitzi Marmorstein. -

Ki Teitzei Review

Dear Youth Directors , Youth chairs, and Youth Leaders, NCYI is excited to continue our very successful Parsha Nation Guides. I hope you’re enjoying and learning from Parsha Nation as much as we are. Putting together Parsha Nation every week is indeed no easy task. It takes a lot of time and effort to ensure that each section, as well as each age group, receives the attention and dedication it deserves. We inspire and mold future leaders. The youth leaders of Young Israel have the distinct honor and privilege to teach and develop the youth of Young Israel. Children today are constantly looking for role models and inspirations to latch on to and learn from. Whether it is actual sit down learning sessions, exciting Parsha trivia games, or even just walking down the hall to the Kiddush room, our youth look to us and watch our every move. It’s not always about the things we say, it’s about the things we do. Our children hear and see everything we do whether we realize it or not. This year we are taking our Youth Services to new heights as we introduce our Leadership Training Shabbaton. This engaging, interactive shabbaton led by our Youth Services Coordinator, Sammy, will give youth leader’s hands on experience and practical solutions to effectively guide your youth department. Informal education is key. What the summer shows us as educators is that informal education can deliver better results and help increase our youth’s connection to Hashem. More and more shuls are revamping their youth program to give their children a better connection to shul and to Hashem. -

One Good Deed Leads to Another

256 | מצוה גוררת מצוה One Good Deed Leads to Another Easy Mitzvot, Difficult Mitzvot Some of the Torah’s commandments appear to be simpler to perform than others. For instance, we learn in Parashat Ki Tetze (D’varim 22,6-7) of the mitzvah of Shiluach HaKen, sending away the mother bird before taking her chicks. !is would seem to be an “easy” mitzvah. Does this mean it is less valuable or important than others? Should we relate to the commandments differently based on their complexity or difficulty? !e answer is provided in Pirkei Avot (Chapters of the Fathers) by Rebbe, R. Yehuda HaNasi: Be as careful and meticulous regarding an easy mitzvah as for a difficult one, for you do not know the reward for each one. (Avot 2,1) Rebbe is telling us that the ease with which mitzvot are carried out means nothing about their relative value, nor about the reward promised to those who fulfill them. !e Jerusalem Talmud provides support for this position in Tractate Peah (1,1): R. Abba bar Kahana says: “!e Torah equated the lightest of the easy mitzvot with the gravest of the difficult mitzvot. !e ‘lightest of the light’ is the mitzvah of Shiluach HaKen , and the ‘gravest of the difficult’ is that of honoring one’s parents. !ey are equated in that the Torah writes regarding both of them (D’varim 5,16 and 22,7), ‘you shall have long life .’ ” One Good Deed Leads to Another | Ki Tetze | 257 Why is this? It would seem logical that the reward for a mitzvah shows its “gravity,” or true weight. -

Why Honor Parents?

Saturday 7 Feb 2015 – 18 Shevat 5775 B”H Dr Maurice M. Mizrahi Congregation Adat Reyim Torah discussion on Yitro Honor your father and your mother Where does it say that? Three places in the Torah: ַּכ ֵּבד ֶאת ָא ִביָך וְ ֶאת ִא ֶמָך Kabed et avicha ve-et immecha. Honor your father and your mother, so that your days may be long in the land the Lord your God gives you. [Exodus 20:12] Honor your father and your mother, as the Lord your God has commanded you, so that your days may be prolonged, and that it may go well with you, in the land the Lord your God gives you. [Deut. 5:16] Ish immo v'aviv tira-u. Every man shall revere his mother and his father. [Leviticus 19:3] (Correct translation is “revere” or “be in awe of”, not “fear”.) It’s called Kibbud Av Va-Em. In honor, father mentioned first; but in reverence, mother mentioned first. Why? Mishna: You might think... the honor due to the father exceeds the honor due to the mother, [but] the Torah stated, “Every man shall revere his mother and his father” to teach that both are equal. [K'ritot 6:9 - 28a; Genesis R. 1:15] Talmud: It was taught that Rabbi [Yehuda HaNasi] said: It is revealed and known to Him Whose decree brought the world into existence, that a son honors his mother more than his father, because she sways him with her words. Therefore, the Holy One, blessed be He, placed the honor of the father before that of the mother. -

Ki Tetzte 2020 for Print

בס''ד l Ki Tetze English version MEANINGFUL IMPACT There are three judgements all souls need to go children that could have come from Hebel through by the Heavenly court. 1. Rosh cried out to G-d for vengeance. Judgment Hashana. 2.When one dies. 3. And at the concerns every outcome, present and future, of resurrection of the dead. (Ramban Shaar one’s actions. Hagmul) Why do we .שמע ישרא-ל ה' אלוקינו ה' אחד We say When King Shaul brought the soul of the mention “Listen Yisrael”, when we accept the prophet, Shmuel, down to earth to ask about yoke of Heaven? Because Judaism is accepting his fate and the upcoming war, Shmuel’s soul G-d in a way that it will have ripple effect, was trembling so much, it brought Moshe influencing other Jews. On Rosh Hashana, we along, as a kind of attorney. Shmuel was are judged as to how effective we are in acting afraid of the judgement of the End of Days, of as channels to bring G-dliness into the world. -How much G .מלוך על כל העולם כולו בכבודך the resurrection of the dead. Why did Shmuel fear Judgment at the End of Days, at the dliness is there in each of our actions? כתבנו בספר חיים למענך (resurrection? Upon his death, he had been (Rambam Deot 3;2 Write us in the Book of Life, so we .אלוקים חיים judged and G-d ruled that he was equal to בְּ כָ ל ־ דְּ רָ כֶ ֥ י � דָ ﬠֵ ֑ ה וּ .can live our life for You, G-d ֮מֹ שֶׁ ֤ ה וְ אַ הֲ רֹ֨ ן׀ בְּ ֽ כֹ הֲ נָ֗ יו !Moshe and Aharon, together ,In all your ways know Him וְ֝ה֗ וּא יְיַשֵּׁ֥ ר אֹֽרְ חֹתֶֽ י� (Tehillim 99) וּ֭שְׁ מוּאֵ ל בְּ קֹרְ אֵ֣י שְׁמ֑ וֹ and He will straighten your paths (Mishlei 3) The Ramchal answers that in the final The whole religion is this passuk, because judgement at the resurrection of the dead, G-d Judaism is about being a vessel to bring G- will judge all the results of your actions, the dliness into the world, into everyday life, with impact you made, for good or for bad, until the whatever He blessed us with. -

Baal Haturim's Insight Highlights the Torah's Sensitivity the Judaism Site

Torah.org Baal HaTurim's Insight Highlights The Torah's Sensitivity The Judaism Site https://torah.org/torah-portion/ravfrand-5767-tazria/ BAAL HATURIM'S INSIGHT HIGHLIGHTS THE TORAH'S SENSITIVITY by Rabbi Yissocher Frand Parshas Tazria Baal HaTurim's Insight Highlights The Torah's Sensitivity These divrei Torah were adapted from the hashkafa portion of Rabbi Yissocher Frand's Commuter Chavrusah Tapes on the weekly portion: Tape # 545 - Dangerous Medical Procedures. Good Shabbos! The Baal HaTurim provides us with a fascinating insight into the purification offerings brought by a woman who has given birth (following the prescribed days of impurity and purity). At the beginning of Parshas Tazria, the Torah specifies the nature of these offerings: A woman who can afford the standard offering is commanded to bring a sheep within its first year as an Olah offering and a young dove (ben yonah) or a turtledove (tor) as a Chatas [sin offering]. [Vayikra 12:6] A woman who has given birth (yoledes) who cannot afford the standard offering of a sheep is allowed to bring two turtledoves (shnei torim) or two young doves (shnei bnei yonah) - one for the Olah offering and one for the sin offering. [Vayikra 12:8]. The Baal HaTurim points out that throughout the Torah -- including the above quoted pasuk 8 -- whenever the torim (turtledoves) and the bnei yonah (young doves) are mentioned, the torim are always mentioned first. Only in pasuk 6 above is the sequence reversed, with the Torah first mentioning the ben yonah and then the tor. He explains the reason as follows.