Iranian Political and Nuclear Realities and U.S. Policy Options

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A/HRC/13/39/Add.1 General Assembly

United Nations A/HRC/13/39/Add.1 General Assembly Distr.: General 25 February 2010 English/French/Spanish only Human Rights Council Thirteenth session Agenda item 3 Promotion and protection of all human rights, civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, including the right to development Report of the Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, Manfred Nowak Addendum Summary of information, including individual cases, transmitted to Governments and replies received* * The present document is being circulated in the languages of submission only as it greatly exceeds the page limitations currently imposed by the relevant General Assembly resolutions. GE.10-11514 A/HRC/13/39/Add.1 Contents Paragraphs Page List of abbreviations......................................................................................................................... 5 I. Introduction............................................................................................................. 1–5 6 II. Summary of allegations transmitted and replies received....................................... 1–305 7 Algeria ............................................................................................................ 1 7 Angola ............................................................................................................ 2 7 Argentina ........................................................................................................ 3 8 Australia......................................................................................................... -

Prepared Testimony to the United States Senate Foreign Relations

Prepared Testimony to the United States Senate Foreign Relations Subcommittee on Near Eastern and South and Central Asian Affairs May 11, 2011 HUMAN RIGHTS AND DEMOCRATIC REFORM IN IRAN Andrew Apostolou, Freedom House Chairman Casey, Ranking member Risch, Members of the Subcommittee, it is an honour to be invited to address you and to represent Freedom House. Please allow me to thank you and your staff for all your efforts to advance the cause of human rights and democracy in Iran. It is also a great pleasure to be here with Rudi Bakhtiar and Kambiz Hosseini. They are leaders in how we communicate the human rights issue, both to Iran and to the rest of the world. Freedom House is celebrating its 70th anniversary. We were founded on the eve of the United States‟ entry into World War II by Eleanor Roosevelt and Wendell Wilkie to act as an ideological counterweight to the Nazi‟s anti-democratic ideology. The Nazi headquarters in Munich was known as the Braunes Haus, so Roosevelt and Wilkie founded Freedom House in response. The ruins of the Braunes Haus are now a memorial. Freedom House is actively promoting democracy and freedom around the world. The Second World War context of our foundation is relevant to our Iran work. The Iranian state despises liberal democracy, routinely violates human rights norms through its domestic repression, mocks and denies the Holocaust. Given the threat that the Iranian state poses to its own population and to the Middle East, we regard Iran as an institutional priority. In addition to Freedom House‟s well-known analyses on the state of freedom in the world and our advocacy for democracy, we support democratic activists in some of the world‟s most repressive societies, including Iran. -

IRAN COUNTRY of ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service

IRAN COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service Date 28 June 2011 IRAN JUNE 2011 Contents Preface Latest News EVENTS IN IRAN FROM 14 MAY TO 21 JUNE Useful news sources for further information REPORTS ON IRAN PUBLISHED OR ACCESSED BETWEEN 14 MAY AND 21 JUNE Paragraphs Background Information 1. GEOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................ 1.01 Maps ...................................................................................................................... 1.04 Iran ..................................................................................................................... 1.04 Tehran ................................................................................................................ 1.05 Calendar ................................................................................................................ 1.06 Public holidays ................................................................................................... 1.07 2. ECONOMY ................................................................................................................ 2.01 3. HISTORY .................................................................................................................. 3.01 Pre 1979: Rule of the Shah .................................................................................. 3.01 From 1979 to 1999: Islamic Revolution to first local government elections ... 3.04 From 2000 to 2008: Parliamentary elections -

Basic Christian 2009 - C Christian Information, Links, Resources and Free Downloads

Sunday, June 14, 2009 16:07 GMT Basic Christian 2009 - C Christian Information, Links, Resources and Free Downloads Copyright © 2004-2008 David Anson Brown http://www.basicchristian.org/ Basic Christian 2009 - Current Active Online PDF - News-Info Feed - Updated Automatically (PDF) Generates a current PDF file of the 2009 Extended Basic Christian info-news feed. http://rss2pdf.com?url=http://www.BasicChristian.org/BasicChristian_Extended.rss Basic Christian 2009 - Extended Version - News-Info Feed (RSS) The a current Extended Basic Christian info-news feed. http://www.BasicChristian.org/BasicChristian_Extended.rss RSS 2 PDF - Create a PDF file complete with links of this current Basic Christian News/Info Feed after the PDF file is created it can then be saved to your computer {There is a red PDF Create Button at the top right corner of the website www.basicChristian.us} Free Online RSS to PDF Generator. http://rss2pdf.com?url=http://www.BasicChristian.org/BasicChristian.rss Updated: 06-12-2009 Basic Christian 2009 (1291 Pages) - The BasicChristian.org Website Articles (PDF) Basic Christian Full Content PDF Version. The BasicChristian.org most complete resource. http://www.basicchristian.info/downloads/BasicChristian.pdf !!! Updated: 2009 Version !!! FREE Download - Basic Christian Complete - eBook Version (.CHM) Possibly the best Basic Christian resource! Download it and give it a try!Includes the Red Letter Edition Holy Bible KJV 1611 Version. To download Right-Click then Select Save Target _As... http://www.basicchristian.info/downloads/BasicChristian.CHM Sunday, June 14, 2009 16:07 GMT / Created by RSS2PDF.com Page 1 of 125 Christian Faith Downloads - A Christian resource center with links to many FREE Mp3 downloads (Mp3's) Christian Faith Downloads - 1st Corinthians 2:5 That your faith should not stand in the wisdom of men, but in the power of God. -

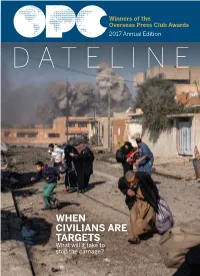

WHEN CIVILIANS ARE TARGETS What Will It Take to Stop the Carnage?

Winners of the Overseas Press Club Awards 2017 Annual Edition DATELINE WHEN CIVILIANS ARE TARGETS What will it take to stop the carnage? DATELINE 2017 1 President’s Letter / dEIdRE dEPkE here is a theme to our gathering tonight at the 78th entries, narrowing them to our 22 winners. Our judging process was annual Overseas Press Club Gala, and it’s not an easy one. ably led by Scott Kraft of the Los Our work as journalists across the globe is under Angeles Times. Sarah Lubman headed our din- unprecedented and frightening attack. Since the conflict in ner committee, setting new records TSyria began in 2011, 107 journalists there have been killed, according the for participation. She was support- Committee to Protect Journalists. That’s more members of the press corps ed by Bill Holstein, past president of the OPC and current head of to die than were lost during 20 years of war in Vietnam. In the past year, the OPC Foundation’s board, and our colleagues also have been fatally targeted in Iraq, Yemen and Ukraine. assisted by her Brunswick colleague Beatriz Garcia. Since 2013, the Islamic State has captured or killed 11 journalists. Almost This outstanding issue of Date- 300 reporters, editors and photographers are being illegally detained by line was edited by Michael Serrill, a past president of the OPC. Vera governments around the world, with at least 81 journalists imprisoned Naughton is the designer (she also in Turkey alone. And at home, we have been labeled the “enemy of the recently updated the OPC logo). -

Iran Relations

August 2021 Lectures in Diplomacy US – Iran Relations By Siham Al-Jiboury – Senior Advisor on the Middle East American writer George Friedman asked: “Do you know what is the most important global event in Bidaya? The twenty-first century after the events of the eleventh from September? It is the US-Iranian alliance.” Iran and the United States have had no formal diplomatic relations since April 1980. Pakistan serves as Iran's protecting power in the United States, while Switzerland serves as the United States' protecting power in Iran. Contacts are carried out through the Iranian Interests Section of the Pakistani Embassy in Washington, D.C., and the US Interests Section of the Swiss Embassy in Tehran. In August 2018, Supreme Leader of Iran Ali Khamenei banned direct talks with the United States. The American newspapers in the 1720s were uniformly pro-Iranian, especially during the Mahmud Hotak's 1722 revolt against the Iranian monarchy. Relations between the two nations began in the mid-to-late 19th century, when Iran was known to the west as Persia. Initially, while Persia was very wary of British and Russian colonial interests during the Great Game, the United States was seen as a more trustworthy foreign power, and the Americans Arthur Millspaugh and Morgan Shuster were even appointed treasurers- general by the Shahs of the time. During World War II, Persia was invaded by the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union, both US allies, but relations continued to be positive after the war until the later years of the government of Mohammad Mosaddegh, who was overthrown by a coup organized by the Central Intelligence Agency and aided by MI6. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

Wednesday Volume 495 8 July 2009 No. 108 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Wednesday 8 July 2009 £5·00 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2009 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Parliamentary Click-Use Licence, available online through the Office of Public Sector Information website at www.opsi.gov.uk/click-use/ Enquiries to the Office of Public Sector Information, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 4DU; Tel: 0044 (0) 208876344; e-mail: [email protected] 949 8 JULY 2009 950 political stability? The twin evils in respect of getting House of Commons investment back into Northern Ireland and getting our economy going are those who use the bomb and the Wednesday 8 July 2009 bullet to kill and cause bloodshed there, and those wreckers who are attempting to bring down the political institutions. The House met at half-past Eleven o’clock Mr. Woodward: I congratulate the right hon. Gentleman PRAYERS on the work that he has been doing to inspire leadership in Northern Ireland, and also on what he has done with the Deputy First Minister in the United States to attract [MR.SPEAKER in the Chair] inward investment. They have been extremely successful, especially in the current climate. The right hon. Gentleman is also right to point to the impact of the activities of those criminals who call themselves dissident republicans. Oral Answers to Questions Again, I congratulate the First Minister and his colleagues on their achievements, which mean that, despite those criminal activities, Northern Ireland continues to be a NORTHERN IRELAND place that attracts that investment. -

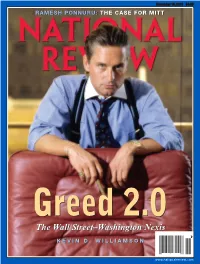

Ramesh Ponnuru:Ponnuru: Thethe Casecase Forfor Mittmitt

2011_12_19_B_cover61404-postal.qxd 11/29/2011 7:57 PM Page 1 December 19, 2011 $4.99 RAMESHRAMESH PONNURU:PONNURU: THETHE CASECASE FORFOR MITTMITT GreedGreed 2.02.0 The Wall Street–Washington Nexis $4.99 51 KEVIN D. WILLIAMSON 0 74820 08155 6 www.nationalreview.com base_milliken-mar 22.qxd 11/28/2011 12:45 PM Page 2 Gutter Trim 1 D : 2400 45˚ 105˚ 75˚ G 2 base_milliken-mar 22.qxd 11/28/2011 12:45 PM Page 3 Best-Of-Boeing Capabilities Cost Reduction Through Innovation High-Efficiency Processes Model Program Management Best-Of-Industry Partners www.boeing.com/value TODAYTOMORROWBEYOND D 105˚ 75˚ toc_QXP-1127940144.qxp 11/30/2011 1:33 PM Page 4 Contents DECEMBER 19, 2011 | VOLUME LXIII, NO. 23 | www.nationalreview.com COVER STORY Page 39 Andrew Stuttaford on Europe Repo Men p. 18 Wall Street wants an administration and a BOOKS, ARTS Congress—and a country—that believe what & MANNERS is good for Wall Street is good for America, whether that is true or isn’t. Wall Street 51 SCHOOL FOR FIGHTING Victor Davis Hanson reviews doesn’t want free markets—it wants Conquered into Liberty: Two friends, favors, and fealty. Kevin D. Williamson Centuries of Battles along the Great Warpath that Made the American Way of War, COVER: HO/RTR/NEWSCOM by Eliot A. Cohen. ARTICLES 52 BE NICE! John Derbyshire reviews The EURO MELEE by Andrew Stuttaford 18 Better Angels of Our Nature: It’s Europe vs. the Europeans. Why Violence Has Declined, 20 JUSTICE FOR LIBYA by John R. Bolton by Steven Pinker. -

From Protest to Prison: Iran One Year After the Election 5

from protest to pri son IrAn onE yEAr AftEr tHE ELECtIon amnesty international is a global movement of 2.8 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of human rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. amnesty international publications first published in 2010 by amnesty international publications international secretariat peter Benenson house 1 easton street london Wc1X 0DW United Kingdom www.amnesty.org © amnesty international publications 2010 index: mDe 13/062/2010 original language: english printed by amnesty international, international secretariat, United Kingdom all rights reserved. this publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. the copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. for copying in any other circumstances, or for re-use in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. Cover phot o: Demonstration in tehran following the disputed 12 June 2009 presidential election. © Javad montazeri Back cover phot o: a mass “show trial” in tehran’s revolutionary court, 25 august 2009; defendants are dressed in grey. © ap/pa photo/fars news agency, hasan Ghaedi CONTENTS 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................5 2. -

Inside Evin Prison Articles/Inside-Evin-Prison

Trial of Iran’s seven Baha’i leaders Inside Evin Prison http://news.bahai.org/human-rights/iran/yaran-special-report/feature- articles/inside-evin-prison For more than two years, the seven Baha’i leaders were held in Tehran’s notorious Evin prison. During her own incarceration, journalist Roxana Saberi shared a cell for three weeks in early 2009 with the two women Baha’i prisoners, Fariba Kamalabadi and Mahvash Sabet. In an account published in One Country, June-November 2009, Ms. Saberi spoke of how they gave her strength and inspiration as she faced the interrogations of her keepers and the harsh conditions of the jail itself. NEW YORK — During her time in Iran’s notorious Evin prison, journalist Roxana Saberi met a number of fellow women prisoners who gave her strength and inspiration as she faced the interrogations of her keepers and the harsh conditions of the jail itself. Among these were two Baha’i prisoners, Fariba Kamalabadi and Mahvash Sabet, with whom Ms. Saberi shared a cell for about three weeks in early 2009. “Fariba and Mahvash were two of the women prisoners I met in Evin who inspired me the most,” said Ms. Saberi in a recent interview. “They showed me what it means to be selfless, to care more about one’s community and beliefs than about oneself.” Ms. Saberi, an Iranian-Japanese-American journalist who was arrested in Tehran, had served about a month of an eight-y e a r sentence for spying when she was released in May 2009, apparently in response to international pressure… Ms. -

Brokaw Receives Standing Ovation at Awards Dinner War Portrayed

THE MONTHLY NEWSLETTER OF THE OVERSEAS PRESS CLUB OF AMERICA, NEW YORK, NY • April/May 2013 Brokaw Receives Standing Ovation at Awards Dinner mie Doran arrived EVENT RECAP: APRIL 24 wearing a tartan kilt by Aimee Vitrak and Fabio Bucci- The past year was just as daunt- arelli wore aviator ing in terms of press freedom and sunglasses, but they its toll on journalists and journalism were award winners as in years past, but the mood in the so shaking up the room managed to be festive. Per- status quo seemed a haps journalists have grown numb part of their job and to the bad news, or at least decided gave a rebel quality to honor those journalists who were to the room. tenacious and even lucky enough The candle that is Michael Dames lit at the beginning to walk away from scenes in Syria, Tom Brokaw accepts the OPC President’s Award China, Southern Africa, Nigeria, of the dinner hon- launched an internet campaign free- Honduras, Afghanistan and many ors those journalists other dangerous and difficult places who are killed or missing in action. jamesfoley.org to raise awareness to tell the story, when so many of This year’s tribute was again a mov- for their son’s situation and to urge their compatriots have not. ing one with Diane and John Foley the Syrian government to release The 74th OPC Annual Awards lighting the candle for all journal- him. The Foleys are all-too familiar Dinner started on the thirty-fifth ists and in particular, for their son to concerns of journalist safety and floor of the Mandarin Oriental James Foley who has been missing press freedom as James was also where guests mingled around two in action in Syria since Thanksgiv- taken for a month by the Libyan well-stocked bars, rounds of hors ing Day 2012. -

Rising Nuclear Risk, Disarmament and the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty

HOUSE OF LORDS Select Committee on International Relations 7th Report of Session 2017–19 Rising nuclear risk, disarmament and the Nuclear Non- Proliferation Treaty Ordered to be printed 3 April 2019 and published 24 April 2019 Published by the Authority of the House of Lords HL Paper 338 Select Committee on International Relations The select Committee on International Relations is appointed by the House of Lords in each session “to investigate the United Kingdom’s International Relations”. Membership The Members of the Select Committee on International Relations are: Baroness Anelay of St Johns Lord Howell of Guildford (Chairman) Baroness Coussins Lord Jopling Lord Grocott Lord Purvis of Tweed Lord Hannay of Chiswick Lord Reid of Cardowan Baroness Helic Baroness Smith of Newnham Baroness Hilton of Eggardon Lord Wood of Anfield Declaration of interests See Appendix 1. A full list of Members’ interests can be found in the Register of Lords’ Interests: http://www. parliament.uk/mps-lords-and-offices/standards-and-interests/register-of-lords- interests Publications All publications of the Committee are available at: http://www.parliament.uk/intl-relations Parliament Live Live coverage of debates and public sessions of the Committee’s meetings are available at: http://www.parliamentlive.tv Further information Further information about the House of Lords and its Committees, including guidance to witnesses, details of current inquiries and forthcoming meetings is available at: http://www. parliament.uk/business/lords Committee staff The current staff of the Committee are Eva George (Clerk), Joseph Dobbs (Policy Analyst) and Thomas Cullen (Committee Assistant). Contact details All correspondence should be addressed to the International Relations Committee Office, House of Lords, London SW1A 0PW.