Prepared Testimony to the United States Senate Foreign Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iran Human Rights Defenders Report 2019/20

IRAN HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENDERS REPORT 2019/20 Table of Contents Definition of terms and concepts 4 Introduction 7 LAWYERS Amirsalar Davoudi 9 Payam Derafshan 10 Mohammad Najafi 11 Nasrin Sotoudeh 12 CIVIL ACTIVISTS Zartosht Ahmadi-Ragheb 13 Rezvaneh Ahmad-Khanbeigi 14 Shahnaz Akmali 15 Atena Daemi 16 Golrokh Ebrahimi-Irayi 17 Farhad Meysami 18 Narges Mohammadi 19 Mohammad Nourizad 20 Arsham Rezaii 21 Arash Sadeghi 22 Saeed Shirzad 23 Imam Ali Popular Student Relief Society 24 TEACHERS Esmaeil Abdi 26 Mahmoud Beheshti-Langroudi 27 Mohammad Habibi 28 MINORITY RIGHTS ACTIVISTS Mary Mohammadi 29 Zara Mohammadi 30 ENVIRONMENTAL ACTIVISTS Persian Wildlife Heritage Foundation 31 Workers rights ACTIVISTS Marzieh Amiri 32 This report has been prepared by Iran Human Rights (IHR) Esmaeil Bakhshi 33 Sepideh Gholiyan 34 Leila Hosseinzadeh 35 IHR is an independent non-partisan NGO based in Norway. Abolition of the Nasrin Javadi 36 death penalty, supporting human rights defenders and promoting the rule of law Asal Mohammadi 37 constitute the core of IHR’s activities. Neda Naji 38 Atefeh Rangriz 39 Design and layout: L Tarighi Hassan Saeedi 40 © Iran Human Rights, 2020 Rasoul Taleb-Moghaddam 41 WOMEN’S RIGHTS ACTIVISTS Raha Ahmadi 42 Raheleh Ahmadi 43 Monireh Arabshahi 44 Yasaman Aryani 45 Mojgan Keshavarz 46 Saba Kordafshari 47 Nedaye Zanan Iran 48 www.iranhr.net Recommendations 49 Endnotes 50 : @IHRights | : @iranhumanrights | : @humanrightsiran Definition of Terms & Concepts PRISONS Evin Prison: Iran’s most notorious prison where Wards 209, 240 and 241, which have solitary cells called security“suites” and are controlled by the Ministry of Intelligence (MOIS): Ward 209 Evin: dedicated to security prisoners under the jurisdiction of the MOIS. -

A/HRC/13/39/Add.1 General Assembly

United Nations A/HRC/13/39/Add.1 General Assembly Distr.: General 25 February 2010 English/French/Spanish only Human Rights Council Thirteenth session Agenda item 3 Promotion and protection of all human rights, civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, including the right to development Report of the Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, Manfred Nowak Addendum Summary of information, including individual cases, transmitted to Governments and replies received* * The present document is being circulated in the languages of submission only as it greatly exceeds the page limitations currently imposed by the relevant General Assembly resolutions. GE.10-11514 A/HRC/13/39/Add.1 Contents Paragraphs Page List of abbreviations......................................................................................................................... 5 I. Introduction............................................................................................................. 1–5 6 II. Summary of allegations transmitted and replies received....................................... 1–305 7 Algeria ............................................................................................................ 1 7 Angola ............................................................................................................ 2 7 Argentina ........................................................................................................ 3 8 Australia......................................................................................................... -

IRAN COUNTRY of ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service

IRAN COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service Date 28 June 2011 IRAN JUNE 2011 Contents Preface Latest News EVENTS IN IRAN FROM 14 MAY TO 21 JUNE Useful news sources for further information REPORTS ON IRAN PUBLISHED OR ACCESSED BETWEEN 14 MAY AND 21 JUNE Paragraphs Background Information 1. GEOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................ 1.01 Maps ...................................................................................................................... 1.04 Iran ..................................................................................................................... 1.04 Tehran ................................................................................................................ 1.05 Calendar ................................................................................................................ 1.06 Public holidays ................................................................................................... 1.07 2. ECONOMY ................................................................................................................ 2.01 3. HISTORY .................................................................................................................. 3.01 Pre 1979: Rule of the Shah .................................................................................. 3.01 From 1979 to 1999: Islamic Revolution to first local government elections ... 3.04 From 2000 to 2008: Parliamentary elections -

CRP News & Background

„ D i s c o v e r i n g I n t e r n a t i o n a l R e l a t i o n s a n d C o n t e m p o r a r y G l o b a l I s s u e s ” Cultural Relations Policy News and Background November 2012 ICRP Monthly Review Series 2012 About CRP News & Background Cultural Relations Policy News & Background is a part of ICRP Monthly Review Series and an initiative of Institute for Cultural Relations Policy Budapest. Launched in 2012, its mission is to provide information and analysis on key international political events. Each issue covers up-to-date events and analysis of current concerns of international relations on a monthly basis. As an initiative of ICRP, the content of this magazine is written and edited by student authors. The project, as part of the Institute’s Internship Programme provides the opportunity to strengthen professional skills. Editorial Team Andras Lorincz, Series Editor Adam Torok, Author – Issue November 2012 Csilla Morauszki, Executive Publisher © Institute for Cultural Relations Policy ICRP Geopolitika Kft 45 Gyongyosi utca, Budapest 1031 - Hungary Contents 01 Ten days of war between Gaza and Israel 05 Catalonia steps closer to independence 07 Austerity unites Europe 08 Storm ended with acquittal 10 Obama presidency continues 12 Rise of Palestine’s status 14 Diplomatic progress of Syrian opposition 17 Goma in the hands of rebels for 10 days 20 Clashes of religions in Nigeria 22 Al-Shabaab stroke back in Kenya 23 Scramble for oil in the Caribbean 25 Asian summits in Cambodia 28 News in Brief 01 ICRP Monthly Review Series | November 2012 Ten days of war between Gaza and Israel Antagonism of Israel and the Hamas sympathiser Palestinians of the Gaza Strip have been tensioning situations in the Middle East for years and caused a long string of incidents. -

Basic Christian 2009 - C Christian Information, Links, Resources and Free Downloads

Sunday, June 14, 2009 16:07 GMT Basic Christian 2009 - C Christian Information, Links, Resources and Free Downloads Copyright © 2004-2008 David Anson Brown http://www.basicchristian.org/ Basic Christian 2009 - Current Active Online PDF - News-Info Feed - Updated Automatically (PDF) Generates a current PDF file of the 2009 Extended Basic Christian info-news feed. http://rss2pdf.com?url=http://www.BasicChristian.org/BasicChristian_Extended.rss Basic Christian 2009 - Extended Version - News-Info Feed (RSS) The a current Extended Basic Christian info-news feed. http://www.BasicChristian.org/BasicChristian_Extended.rss RSS 2 PDF - Create a PDF file complete with links of this current Basic Christian News/Info Feed after the PDF file is created it can then be saved to your computer {There is a red PDF Create Button at the top right corner of the website www.basicChristian.us} Free Online RSS to PDF Generator. http://rss2pdf.com?url=http://www.BasicChristian.org/BasicChristian.rss Updated: 06-12-2009 Basic Christian 2009 (1291 Pages) - The BasicChristian.org Website Articles (PDF) Basic Christian Full Content PDF Version. The BasicChristian.org most complete resource. http://www.basicchristian.info/downloads/BasicChristian.pdf !!! Updated: 2009 Version !!! FREE Download - Basic Christian Complete - eBook Version (.CHM) Possibly the best Basic Christian resource! Download it and give it a try!Includes the Red Letter Edition Holy Bible KJV 1611 Version. To download Right-Click then Select Save Target _As... http://www.basicchristian.info/downloads/BasicChristian.CHM Sunday, June 14, 2009 16:07 GMT / Created by RSS2PDF.com Page 1 of 125 Christian Faith Downloads - A Christian resource center with links to many FREE Mp3 downloads (Mp3's) Christian Faith Downloads - 1st Corinthians 2:5 That your faith should not stand in the wisdom of men, but in the power of God. -

Iran 2019 Human Rights Report

IRAN 2019 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Islamic Republic of Iran is an authoritarian theocratic republic with a Shia Islamic political system based on velayat-e faqih (guardianship of the jurist). Shia clergy, most notably the rahbar (supreme leader), and political leaders vetted by the clergy dominate key power structures. The supreme leader is the head of state. The members of the Assembly of Experts are nominally directly elected in popular elections. The assembly selects and may dismiss the supreme leader. The candidates for the Assembly of Experts, however, are vetted by the Guardian Council (see below) and are therefore selected indirectly by the supreme leader himself. Ayatollah Ali Khamenei has held the position since 1989. He has direct or indirect control over the legislative and executive branches of government through unelected councils under his authority. The supreme leader holds constitutional authority over the judiciary, government-run media, and other key institutions. While mechanisms for popular election exist for the president, who is head of government, and for the Islamic Consultative Assembly (parliament or majles), the unelected Guardian Council vets candidates, routinely disqualifying them based on political or other considerations, and controls the election process. The supreme leader appoints half of the 12-member Guardian Council, while the head of the judiciary (who is appointed by the supreme leader) appoints the other half. Parliamentary elections held in 2016 and presidential elections held in 2017 were not considered free and fair. The supreme leader holds ultimate authority over all security agencies. Several agencies share responsibility for law enforcement and maintaining order, including the Ministry of Intelligence and Security and law enforcement forces under the Interior Ministry, which report to the president, and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), which reports directly to the supreme leader. -

Download Full Text

Annual Report 2019 Published March 2019 Copyright©2019 The Women’s Committee of the National Council of Resistance of Iran (NCRI) All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. ISBN: 978- 2 - 35822 - 010 -1 women.ncr-iran.org @womenncri @womenncri Annual Report 2018-2019 Foreword ast year, as we were preparing our Annual Report, Iran was going through a Table of Contents massive outbreak of protests which quickly spread to some 160 cities across the Lcountry. One year on, daily protests and nationwide uprisings have turned into a regular trend, 1 Foreword changing the face of an oppressed nation to an arisen people crying out for freedom and regime change in all four corners of the country. Iranian women also stepped up their participation in protests. They took to the streets at 2 Women Lead Iran Protests every opportunity. Compared to 436 protests last year, they participated in some 1,500 pickets, strikes, sit-ins, rallies and marches to demand their own and their people’s rights. 8 Women Political Prisoners, Strong and Steady Iranian women of all ages and all walks of life, young students and retired teachers, nurses and farmers, villagers and plundered investors, all took to the streets and cried 14 State-sponsored Violence Against Women in Iran out for freedom and demanded their rights. -

And Second- Generation of Afghan Immigrants Residing in Iran: a Case Study of Southeast of Tehran

35 Journal of Geography and Spatial Justice .Year 1th - Vol.1 – No 1, Winter2018, pp: 35-44 University of Mohaghegh Ardabili Journal of Geography and Spatial Justice Received:2018/01/05 accepted:2018/03/05 A comparative study of the quality of urban life between the first- and second- generation of Afghan immigrants residing in Iran: A case study of southeast of Tehran Saeed Zanganeh Shahraki *1, Hossein HatamiNejad 2, Yaghob Abdali 3, Vahid Abbasi Fallah 4 1 Assistant Professor, Department of Geography and Urban Planning, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran. 2 Associate Professor, Department of Geography and Urban Planning, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran. 3 Ph.D. Student, Department of Geography and Urban Planning, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran. 4 Ph.D. Student, Department of Geography and Urban Planning, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran * Corresponding Author, Email: [email protected] A B S T R A C T Islamic Republic of Iran hosts the largest refugee populations in the world. According to the statistics officially announced in 2007, there are 1,025,000 refugees in Iran, among whom 940,400 refugees are Afghan and 54,400 refugees are Iraqi. After a period of settling and living in the host community, changes begin to occur in the immigrants' quality of life over time and the lives of the second generation of immigrants undergo greater changes than those of the first generation. The present study aims to explore the differences between the two groups of first- and second- generation of Afghan refugees living in Iran in terms of their quality of life in general and their job quality in particular. -

Migrations and Social Mobility in Greater Tehran: from Ethnic Coexistence to Political Divisions?

Migrations and social mobility in greater Tehran : from ethnic coexistence to political divisions? Bernard Hourcade To cite this version: Bernard Hourcade. Migrations and social mobility in greater Tehran : from ethnic coexistence to political divisions?. KUROKI Hidemitsu. Human mobility and multi-ethnic coexistence in Middle Eastern Urban societies1. Tehran Aleppo, Istanbul and Beirut. , 102, Research Institute for languages and cultures of Asia and Africa, Tokyo University of Foreign Languages, pp.27-40, 2015, Studia Culturae Islamicae, 978-4-86337-200-9. hal-01242641 HAL Id: hal-01242641 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01242641 Submitted on 13 Dec 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. LIST OF CONTRIBUTORS Bernard Hourcade is specializing in geography of Iran and Research Director Emeritus of Le Centre national de la recherche scientifique. His publication includes L'Iran au 20e siècle : entre nationalisme, islam et mondialisation (Paris: Fayard, 2007). Aïda Kanafani-Zahar is specializing in Anthropology and Research Fellow of Le Centre national de la recherche scientifique, affiliating to Collège de France. Her publication includes Liban: le vivre ensemble. Hsoun, 1994-2000 (Paris: Librairie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner, 2004). Stefan Knost is specializing in Ottoman history of Syria and Acting Professor of Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg. -

Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights in the Islamic Republic of Iran, Ahmed Shaheed*,**

A/HRC/28/70 Advance Unedited Version Distr.: General 12 March 2015 Original: English Human Rights Council Twenty-eighth session Agenda item 4 Human rights situations that require the Council’s attention Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Islamic Republic of Iran, Ahmed Shaheed*,** Summary In the present report, the fourth to be submitted to the Human Rights Council pursuant to Council resolution 25/24, the Special Rapporteur highlights developments in the situation of human rights in the Islamic Republic of Iran since his fourth interim report submitted to the General Assembly (A/68/503) in October 2013. The report examines ongoing concerns and emerging developments in the State’s human rights situation. Although the report is not exhaustive, it provides a picture of the prevailing situation as observed in the reports submitted to and examined by the Special Rapporteur. In particular, and in view of the forthcoming adoption of the second Universal Periodic Review of the Islamic Republic of Iran, it analysis these in light of the recommendations made during the UPR process. * Late submission. ** The annexes to the present report are circulated as received, in the language of submission only. GE.15- A/HRC/28/70 Contents Paragraphs Page I. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1-5 3 II. Methodology ........................................................................................................... 6-7 4 III. Cooperation -

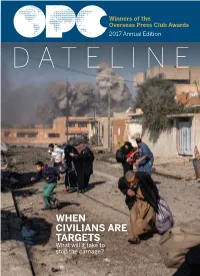

WHEN CIVILIANS ARE TARGETS What Will It Take to Stop the Carnage?

Winners of the Overseas Press Club Awards 2017 Annual Edition DATELINE WHEN CIVILIANS ARE TARGETS What will it take to stop the carnage? DATELINE 2017 1 President’s Letter / dEIdRE dEPkE here is a theme to our gathering tonight at the 78th entries, narrowing them to our 22 winners. Our judging process was annual Overseas Press Club Gala, and it’s not an easy one. ably led by Scott Kraft of the Los Our work as journalists across the globe is under Angeles Times. Sarah Lubman headed our din- unprecedented and frightening attack. Since the conflict in ner committee, setting new records TSyria began in 2011, 107 journalists there have been killed, according the for participation. She was support- Committee to Protect Journalists. That’s more members of the press corps ed by Bill Holstein, past president of the OPC and current head of to die than were lost during 20 years of war in Vietnam. In the past year, the OPC Foundation’s board, and our colleagues also have been fatally targeted in Iraq, Yemen and Ukraine. assisted by her Brunswick colleague Beatriz Garcia. Since 2013, the Islamic State has captured or killed 11 journalists. Almost This outstanding issue of Date- 300 reporters, editors and photographers are being illegally detained by line was edited by Michael Serrill, a past president of the OPC. Vera governments around the world, with at least 81 journalists imprisoned Naughton is the designer (she also in Turkey alone. And at home, we have been labeled the “enemy of the recently updated the OPC logo). -

A Data Mining Approach on Lorry Drivers Overloading in Tehran Urban Roads

Hindawi Journal of Advanced Transportation Volume 2020, Article ID 6895407, 10 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/6895407 Research Article A Data Mining Approach on Lorry Drivers Overloading in Tehran Urban Roads Ehsan Ayazi and Abdolreza Sheikholeslami Iran University of Science and Technology, Tehran, Iran Correspondence should be addressed to Abdolreza Sheikholeslami; [email protected] Received 6 November 2019; Revised 5 May 2020; Accepted 22 May 2020; Published 10 June 2020 Academic Editor: Maria Castro Copyright © 2020 Ehsan Ayazi and Abdolreza Sheikholeslami. (is is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. (e aim of this study is to identify the important factors influencing overloading of commercial vehicles on Tehran’s urban roads. (e weight information of commercial freight vehicles was collected using a pair of portable scales besides other information needed including driver information, vehicle features, load, and travel details by completing a questionnaire. (e results showed that the highest probability of overloading is for construction loads. Further, the analysis of the results in the lorry type section shows that the least likely occurrence of overloading is among pickup truck drivers such that this likelihood within this group was one-third among Nissan and small truck drivers. Also, the results of modeling the type of route showed that the highest likelihood of overloading is for internal loads (origin and destination inside Tehran), and the least probability of overloading is for suburban trips (origin and destination outside of Tehran).