Armillaria Root Rot (Also Known As Mushroom Root Rot, Shoestring Root Rot, Honey Mushroom Rot) 1 Laura Sanagorski, Aaron Trulock, and Jason Smith2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mushroom Root Rot Republished for the Internet April 2008

FOREST AND SHADE TREE PESTS Leaflet Number 11 Published Feb 1994 Mushroom Root Rot Republished for the Internet April 2008 SIGNIFICANCE Mushroom Root Rot, caused by the fungus Armillaria tabescens (syn. Clitocybe tabescens and Armillariella tabescens), is a common and widespread disease affecting both conifers and hardwoods in Florida. This disease occurs statewide and has been reported on more than 200 species of trees and shrubs. RECOGNITION Affected plants can show one or more of a variety of symptoms, including: thinning of the crown, yellowing of foliage, premature defoliation, branch dieback, decaying roots, Fig. 1. Typical cluster of mushrooms of Armillaria tabescens. At right, cluster windthrow, and lesions at excavated and displayed to show common base and spore-producing gills under mushroom caps. the root collar. Some host plants show symptoms of decline for several years before dying. Others die rapidly without any obvious prior symptoms. Mushroom root rot can often be identified without laboratory diagnosis. Conspicuous clusters of mushrooms, (Fig. 1.) which sometimes appear near the base of infected trees, are the most easily recognized diagnostic indicators of the disease. These mushrooms are usually produced in the fall, but they can occur at other times as well. When fresh they are tan to brown, fleshy, with gills beneath the cap, and lacking a ring (annulus) around the stem. While the presence of the characteristic mushrooms is a sure indicator of mushroom root rot, the lack of these fruiting bodies does not indicate the absence of disease. Mushrooms are not formed every year and they decay rapidly when they do appear. -

Field Guide to Common Macrofungi in Eastern Forests and Their Ecosystem Functions

United States Department of Field Guide to Agriculture Common Macrofungi Forest Service in Eastern Forests Northern Research Station and Their Ecosystem General Technical Report NRS-79 Functions Michael E. Ostry Neil A. Anderson Joseph G. O’Brien Cover Photos Front: Morel, Morchella esculenta. Photo by Neil A. Anderson, University of Minnesota. Back: Bear’s Head Tooth, Hericium coralloides. Photo by Michael E. Ostry, U.S. Forest Service. The Authors MICHAEL E. OSTRY, research plant pathologist, U.S. Forest Service, Northern Research Station, St. Paul, MN NEIL A. ANDERSON, professor emeritus, University of Minnesota, Department of Plant Pathology, St. Paul, MN JOSEPH G. O’BRIEN, plant pathologist, U.S. Forest Service, Forest Health Protection, St. Paul, MN Manuscript received for publication 23 April 2010 Published by: For additional copies: U.S. FOREST SERVICE U.S. Forest Service 11 CAMPUS BLVD SUITE 200 Publications Distribution NEWTOWN SQUARE PA 19073 359 Main Road Delaware, OH 43015-8640 April 2011 Fax: (740)368-0152 Visit our homepage at: http://www.nrs.fs.fed.us/ CONTENTS Introduction: About this Guide 1 Mushroom Basics 2 Aspen-Birch Ecosystem Mycorrhizal On the ground associated with tree roots Fly Agaric Amanita muscaria 8 Destroying Angel Amanita virosa, A. verna, A. bisporigera 9 The Omnipresent Laccaria Laccaria bicolor 10 Aspen Bolete Leccinum aurantiacum, L. insigne 11 Birch Bolete Leccinum scabrum 12 Saprophytic Litter and Wood Decay On wood Oyster Mushroom Pleurotus populinus (P. ostreatus) 13 Artist’s Conk Ganoderma applanatum -

Florida Blueberry Pollination Factsheet

Florida Blueberry PROJECT ICP Pollination Blueberries Require Pollination Blueberries need to be cross-pollinated with another cultivar of the same species (rabbiteye or southern highbush blueberry) in order to produce fruit. Cross-pollination allows for better fruit set, berry size, and earlier ripening. Most growers bring in managed European honey bee hives or commercial bumble bees for pollination. Several types of wild bees are also effective and abundant pollinators of Florida blueberries. All of these different kinds of bees visit blueberry flowers to collect pollen and nectar to feed their young. Integrated Crop Pollination: combining strategies to improve pollination Having many different species of pollinators can help ensure reliable pollination. Different species of bees tend to visit flowers at different times of the day and are active at different times throughout the bloom season; having a diverse set of bees active in your fields can ensure consistent pollination from the beginning to the end of crop bloom. Honey bee abundance and wild bee diversity are both important contributors to southeastern US blueberry pollination. Cool, rainy, and windy spring weather can lead to poor pollination. When multiple pollinator species are active, more flowers are likely to be visited on poor weather days. Large-bodied bees, including all three types of wild bees that visit Florida blueberry flowers, stay more active under Pollination is essential for blueberry production. On the left, a blueberry cluster that was enclosed in a mesh bag during cool and cloudy conditions than do honey bees and can help bloom to exclude pollinators. On the right, a blueberry cluster pollinate the crop in variable spring weather. -

Shoestring Root Rot - a Cause of Tree and Shrub Decline

PPFS-OR-W-05 Plant Pathology Fact Sheet Shoestring Root Rot - A Cause of Tree and Shrub Decline By John Hartman Most woody landscape plants are susceptible to shoestring root rot, cause of dieback and decline in the landscape. Diagnosis of this problem requires close examination of the base of the trunk which often reveals loose or decayed bark and dead cambium. By peeling back the bark one can often observe dark brown rhizomorphs (thick strands of hyphae), resembling narrow “shoestrings” (Figure 1). FIGURE 1. ARMILLARIA RHIZOMORPHS These rhizomorphs are signs of one or more species of Armillaria and perhaps other This disease is sometimes confused with related fungi, cause of shoestring root rot. Phytophthora root and collar rot. The decay Decayed roots with rhizomorphs growing associated with Phytophthora is usually a along their surface can be observed by darker brown color, decayed bark is more digging up the roots. moist, and rhizomorphs are absent. Creamy white fans of fungal mycelium Shoestring root rot has a very wide host range may also be observed under the bark. The and is most frequently observed in oaks, mushroom stage (Figure 2) of shoestring maples, pines, hornbeams, taxus, and fruit root rot sometimes develops in fall on dead trees in the landscape. Often, it is associated trees or decayed logs. with formerly wooded sites converted to landscapes because the fungus can persist Shoestring root rot is also called Armillaria for many years in decaying wood in soil. root rot, mushroom root rot, and oak root rot. Most trees with Armillaria root rot are trees Once trees or shrubs begin to show serious symptoms of decline, including dieback of twigs and branches, undersized and off-color leaves, increased trunk and limb sprouts (epicormic branching), and excessive fruit set, the decline is often not reversible. -

A Nomenclatural Study of Armillaria and Armillariella Species

A Nomenclatural Study of Armillaria and Armillariella species (Basidiomycotina, Tricholomataceae) by Thomas J. Volk & Harold H. Burdsall, Jr. Synopsis Fungorum 8 Fungiflora - Oslo - Norway A Nomenclatural Study of Armillaria and Armillariella species (Basidiomycotina, Tricholomataceae) by Thomas J. Volk & Harold H. Burdsall, Jr. Printed in Eko-trykk A/S, Førde, Norway Printing date: 1. August 1995 ISBN 82-90724-14-4 ISSN 0802-4966 A Nomenclatural Study of Armillaria and Armillariella species (Basidiomycotina, Tricholomataceae) by Thomas J. Volk & Harold H. Burdsall, Jr. Synopsis Fungorum 8 Fungiflora - Oslo - Norway 6 Authors address: Center for Forest Mycology Research Forest Products Laboratory United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service One Gifford Pinchot Dr. Madison, WI 53705 USA ABSTRACT Once a taxonomic refugium for nearly any white-spored agaric with an annulus and attached gills, the concept of the genus Armillaria has been clarified with the neotypification of Armillaria mellea (Vahl:Fr.) Kummer and its acceptance as type species of Armillaria (Fr.:Fr.) Staude. Due to recognition of different type species over the years and an extremely variable generic concept, at least 274 species and varieties have been placed in Armillaria (or in Armillariella Karst., its obligate synonym). Only about forty species belong in the genus Armillaria sensu stricto, while the rest can be placed in forty-three other modem genera. This study is based on original descriptions in the literature, as well as studies of type specimens and generic and species concepts by other authors. This publication consists of an alphabetical listing of all epithets used in Armillaria or Armillariella, with their basionyms, currently accepted names, and other obligate and facultative synonyms. -

Root Diseases Diagnosis of Root Diseases Can Be Very Challenging Armillaria Root Disease • Symptoms Can Be Similar for Different Root Diseases • Below Ground Attacks

Root Diseases Diagnosis of root diseases can be very challenging Armillaria root disease • Symptoms can be similar for different root diseases • Below ground attacks but above ground Heterobasision annosum symptoms Annosus root disease • Signs are rare and often are produced once a year for short periods Chronosequence of stand and tree level symptoms of root diseases Source: Fig.12.10, p.312 Forest Health and Protection by Edmonds, R. L., J. K. Agee and R. I. Gara. 2011. Waveland Press, Long Grove, IL. 2nd ed. Used with permission from Waveland Press Dec.13, 2011. Tree level symptoms of Armillaria root disease CC BY 3.0. Borys M. Tkacz, USFS, Bugwood.orgTkacz, BorysM. 3.0. CC BY Tree level symptoms of Armillaria root disease • Dead saplings next to stumps, retaining needles • Roots of young trees grow into the dead roots infected by Armillaria, come into contact with rhizomorphs and get infected Signs of Armillaria root disease • Rhizomorphs: specialized highly adapted structures • Allow the pathogen to explore the “Rhizomorphs (thick fungal threads) of Armillaria mellea” Lairich Rig. CC BY-SA 2.0. environment and http://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/933530 survive in the soil for decades • Contain melanin, a protective compound Cross section of rhizomorph showing differentiated tissue Signs of Armillaria root disease • Armillaria attacks the living cambium of tree roots • Mycelial fans form under the bark of infected trees • The mycelium is very strong and can grow under and lift the bark, leaving imprints Signs of Armillaria root disease -

ARMILLARIA ROOT ROT: a DISEASE of NATIVE and INTRODUCED TREES Forests Fact Sheet

ARMILLARIA ROOT ROT: A DISEASE December 2003 OF NATIVE AND INTRODUCED TREES ISSN 1440-2262 Ian W. Smith & David I. Smith, Forest Science Centre Background Armillaria root rot, unlike some familiar pests and diseases, occurs naturally in many forests of Victoria. This aggressive fungal pathogen has so far seriously damaged about 2000 ha of mixed species eucalypt forest in the Mt. Cole and Wombat State Forests with minor outbreaks in other areas of Victoria. It attacks many species of native trees and shrubs including eucalypts and wattles, and has also been recorded on introduced trees and shrubs growing in parks and botanical and domestic gardens. Symptoms and Signs of disease The fungus can kill trees and shrub species of any age and has a very wide host range. Young trees and seedlings may, over a period of a few weeks, suddenly wilt and the leaves fall. They may die within 3-6 months of the onset of the first symptoms. Larger trees, especially those with a sizeable trunk, die more slowly. The initial symptoms of sparse foliage and branch dieback may continue for up to 3 years before the remaining foliage begins to wilt, the leaves turn brown and the trees die (Figure 1). Other pathogens and environmental disorders can produce similar symptoms, so it is wise to check that Armillaria infection is present by examining a tree showing advanced disease symptoms. To do this, remove some of the inner bark at the base of the tree and look for fan-shaped, creamy-white fungal sheets (Figure 2). Often the bark tissue around the fungal sheets turns chocolate brown in colour. -

For Better Heart Health, Avoid These Foods If You Have High Triglycerides Too Many Starchy Foods Some Vegetables Are Better Than Others

For Better Heart Health, Avoid These Foods If You Have High Triglycerides Too Many Starchy Foods Some vegetables are better than others. Limit how much you eat of those that are starchy, like corn and peas. Too much pasta, potatoes, or cereals can raise triglycerides. Eat them in moderation. A serving is a slice of bread, 1/3 cup of rice or pasta, or half a cup of potatoes or cooked oatmeal. Baked Beans with Sugar or Pork Added Beans have fiber and other nutrients going for them. But if they're made with sugar or pork, they may not be the best choice. The label on the can should say what's in there, and how much sugar and fat you're getting. Switch to black beans, which are a great source of fiber and protein, without saturated fats or added sugar. Too Much of a Good Thing Fruit is good for you especially if you are having it in place of a rich dessert. When you have high triglycerides, you may need to limit yourself to 2-3 pieces of fruit a day. Alcohol You may think of alcohol as being good for your heart. But too much of it can drive up your triglyceride levels. That is because of the sugars that are naturally part of alcohol, whether it is wine, beer, or liquor. Too much sugar, from any source, can be a problem. Your doctor may recommend that you not drink at all if your triglyceride levels are very high. Foods with Added Sugar, Sugary Drinks, Honey, Maple Syrup, Candy and Other Desserts Limit sweet tea, regular soda, specialty coffee drinks to no more than 8 ounces per day. -

Natural Sweeteners

Natural Sweeteners Why do we crave sweets? Are there times when you absolutely crave chocolates, candies, or cakes? The average American consumes well over 20 teaspoons of added sugar on a daily basis, which adds up to an average of 142 pounds of sugar per person, per year!1 That’s more than two times what the USDA recommends. Below you will find information on natural sweeteners, all of which are less processed than refined white sugar, and create fewer fluctuations in blood sugar levels. Although these sweeteners are generally safer alternatives to white sugar, they should only be used in moderation. Agave Nectar Agave nectar, or agave syrup, is a natural liquid sweetener made from the juice of the agave cactus. Many diabetics use agave nectar as an alternative to refined sugars and artificial sweeteners because of its relatively low effect on blood glucose levels2. However, agave is high in fructose and has been under much scrutiny due to possible manufacturing processes which are similar to that of high fructose corn syrup. Some research suggests that fructose affects the hormone lepitin, which controls your appetite and satiety. Too much fructose may result in overeating and weight gain, so it’s important to consume agave nectar in reasonable moderation3. Barley Malt Barley malt syrup is a thick, sticky, brown sweetener and is about half as sweet as refined white sugar. It is made from the soaking, sprouting, mashing, cooking and roasting of barley. Many consumers prefer this natural sweetener because it moves through the digestive system slower than other refined sugars4. -

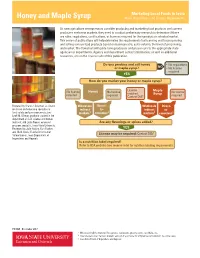

Honey and Maple Syrup Rules, Regulations, and License Requirements

Marketing Local Foods in Iowa Honey and Maple Syrup Rules, Regulations, and License Requirements As new agriculture entrepreneurs consider producing and marketing food products and current producers seek new markets, they need to conduct preliminary research to determine if there are rules, regulations, certifications, or licenses required for their product or selected market. This series of publications will help determine the requirements for licensing and for processing and selling various food products based on business size, sales volume, the level of processing, and market. The flowchart will guide Iowa producers and processors to the appropriate state agencies or departments. Agency and department contact information, as well as additional resources, are on the reverse side of this publication. Do you produce and sell honey • No regulations or maple syrup? NO • No license required YES How do you market your honey or maple syrup? License Maple No license Honey No license No license required required. Syrup required Contact DIA3 required Prepared by Shannon Coleman, assistant Wholesale Direct- Wholesale Direct- professor and extension specialist in indirect to- indirect to- food safety and consumer production; markets1 consumer 2 markets1 consumer 2 Leah M. Gilman, graduate student in the department of food science and human nutrition; and Linda Naeve, extension Are any flavorings or spices added? program specialist, Iowa State University. Reviewed by Julie Kraling, Kurt Rueber, YES and Mark Speltz, Food and Consumer 3 Safety Bureau, Iowa Department of License may be required: Contact DIA Inspections and Appeals. Is a nutrition label required? Refer to FDA website (see reverse side) for nutrition labeling requirements. -

Detection, Recognition and Management Options for Armillaria Root Disease in Urban Environments

Detection, recognition and management options for Armillaria root disease in urban environments Richard Robinson Department of Environment and Conservation, Manjimup, WA 6258 Email: [email protected] Abstract Armillaria luteobubalina, the Australian honey fungus, is an endemic pathogen that attacks and kills the roots of susceptible trees and shrubs, causing a root rot. The fungus colonises the cambium and trees eventually die when the root collar is girdle and it spreads from host to host by root contact. The disease is referred to as armillaria root disease (ARD). In recent years, reports of ARD killing trees and shrubs in urban parks and gardens have increased. When investigated, infection is usually traced to stumps or the roots of infected trees that were left following clearing of the bush when towns or new suburbs were established. The Australian honey fungus is indigenous to southern Australia, and is common in all forest, woodland and some coastal heath communities. In undisturbed environments, ARD is generally not the primary cause of death of healthy forest or woodland trees but more usually it kills trees weakened by competition, age-related decline or environmental stress and disturbance. In gardens and parks, however, the honey fungus can become a particularly aggressive pathogen and in this situation no native or ornamental trees and shrubs appear to be resistant to infection. The life cycle of the fungus consists of a parasitic phase during which the host is infected and colonised. The time taken for plants to succumb to disease varies, but may take decades for large trees. A saprophytic phase follows, during which the root system and stump of the dead host is used by the fungus as a food base. -

Armillaria (Tricholomataceae, Agari Cales) in the Western United States Including a New Species from California

448 MADROÑO [Vol. 23 Smith, G. M. 1944. Marine algae of the Monterey peninsula, California. Stanford Univ. Press, Stanford, California. Suhr, J. N. 1834. Übersicht der Algen, welche von Hrn. Eckion an der südafrikani- schen Küste gefunder worden sind. Flora 17:721-735, 737-743. Taylor, W. R. 1945. Pacific marine algae of the Allan Hancock Expeditions to the Galapagos Islands. Allan Hancock Pacific Exped. 12:1-528. Univ. Michigan Press, Ann Arbor. Wynne, M. J. 1970. Marine algae of Amchitka Island (Aleutian Islands). I. Deles- seriaceae. Syesis 3:95-144. ARMILLARIA (TRICHOLOMATACEAE, AGARI CALES) IN THE WESTERN UNITED STATES INCLUDING A NEW SPECIES FROM CALIFORNIA Harry D. Thiers Department of Biology, San Francisco State University, San Francisco, California 94132 Walter J. Sundberg Department of Botany, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale 62901 Armillwria Kummer has, to a large extent, been neglected by agaricol- ogists, and no extensive treatment of North American species has ap- peared since that of Kauffman (1922). Prior to his publication, the only available treatment of the genus was that of Murrill (1914). Both of these works are difficult to use because many species that no longer be- long in Armillaria are included. The common occurrence of a new spe- cies, described below, as well as the frustration resulting from the inability to identify numerous collections belonging to this genus, stimu- lated us to devote some time to the taxonomy of the species that occur in California, and, to a lesser extent, to those occurring in western United States. Results of this investigation along with a key to western North American Armillarias are presented below.