The Gluten-Free, Casein-Free Diet and Autism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Overview of Biomedical Treatments Presentation

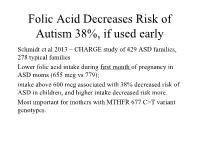

Folic Acid Decreases Risk of Autism 38%, if used early Schmidt et al 2013 – CHARGE study of 429 ASD families, 278 typical families Lower folic acid intake during first month of pregnancy in ASD moms (655 mcg vs 779); intake above 600 mcg associated with 38% decreased risk of ASD in children, and higher intake decreased risk more. Most important for mothers with MTHFR 677 C>T variant genotypes. Folic Acid decreases risk of ASD if taken near conception (cont.) Suren et al 2013 – study of 85,176 Norwegian children, including 270 with ASD. In children whose mothers took folic acid (400 mcg) between 4 weeks prior to conception to 8 weeks after conception, 0.10% (64/61 042) had autistic disorder, compared with 0.21% (50/24 134) in those unexposed to folic acid. 39% lower risk of ASD in those who took prenatal folic acid (400 mcg); Little benefit if taken after 8 weeks Overview of Dietary, Nutritional, and Medical Treatments for Autism James B. Adams, Ph.D. President’s Professor, Arizona State University President, Autism Society of Greater Phoenix President, Autism Nutrition Research Center Chair of Scientific Advisory Board, Neurological Health Foundation Father of a daughter with autism http://autism.asu.edu Our research group is dedicated to finding the causes of autism, how to prevent autism, and how to best help people with autism. Nutrition: vitamins, minerals, fatty acids, amino acids Metabolism: glutathione, methylation, sulfation, oxidative stress Mitochondria – ATP, muscle strength, carnitine Toxic Metals and Chelation Gastrointestinal -

Measuring the Effectiveness of Play As an Intervention to Support

Measuring the Effectiveness of Play as an Intervention to Support Language Development in Young Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Hierarchically- Modeled Meta-Analysis by Gregory V. Boerio Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Education in the Educational Leadership Program Youngstown State University May, 2021 Measuring the Effectiveness of Play as an Intervention to Support Language Development in Young Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Hierarchically- Modeled Meta-Analysis Gregory V. Boerio I hereby release this dissertation to the public. I understand that this dissertation will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: _______________________________________________________________ Gregory V. Boerio, Student Date Approvals: _______________________________________________________________ Dr. Karen H. Larwin, Dissertation Chair Date _______________________________________________________________ Dr. Patrick T. Spearman, Committee Member Date _______________________________________________________________ Dr. Carrie R. Jackson, Committee Member Date _______________________________________________________________ Dr. Matthew J. Erickson, Committee Member Date _______________________________________________________________ Dr. Salvatore A. Sanders, Dean of Graduate Studies Date ii © G. Boerio 2021 iii Abstract The purpose of the current investigation is to analyze extant research examining the impact of play therapy on the development of language skills in young children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). As rates of ASD diagnoses continue to increase, families and educators are faced with making critical decisions regarding the selection and implementation of evidence-based practices or therapies, including play-based interventions, to support the developing child as early as 18 months of age. -

Environmental and Genetic Factors in Autism Spectrum Disorders: Special Emphasis on Data from Arabian Studies

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Review Environmental and Genetic Factors in Autism Spectrum Disorders: Special Emphasis on Data from Arabian Studies Noor B. Almandil 1,† , Deem N. Alkuroud 2,†, Sayed AbdulAzeez 2, Abdulla AlSulaiman 3, Abdelhamid Elaissari 4 and J. Francis Borgio 2,* 1 Department of Clinical Pharmacy Research, Institute for Research and Medical Consultation (IRMC), Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, Dammam 31441, Saudi Arabia; [email protected] 2 Department of Genetic Research, Institute for Research and Medical Consultation (IRMC), Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, Dammam 31441, Saudi Arabia; [email protected] (D.N.A.); [email protected] (S.A.) 3 Department of Neurology, College of Medicine, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, Dammam 31441, Saudi Arabia; [email protected] or [email protected] 4 Univ Lyon, University Claude Bernard Lyon-1, CNRS, LAGEP-UMR 5007, F-69622 Lyon, France; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel.: +966-13-333-0864 † These authors contributed equally to this work. Received: 26 January 2019; Accepted: 19 February 2019; Published: 23 February 2019 Abstract: One of the most common neurodevelopmental disorders worldwide is autism spectrum disorder (ASD), which is characterized by language delay, impaired communication interactions, and repetitive patterns of behavior caused by environmental and genetic factors. This review aims to provide a comprehensive survey of recently published literature on ASD and especially novel insights into excitatory synaptic transmission. Even though numerous genes have been discovered that play roles in ASD, a good understanding of the pathophysiologic process of ASD is still lacking. -

Autism Handout

Autism, a Pervasive Dilemma Developed by Alan Ascher New York State Biology-Chemistry Professional Development Network For the My Environment, My Health, My Choices project University of Rochester Rochester, NY Abstract: Research suggests that autism may be due to a combination of environmental factors which impact genetic information and lead to errors in the development process during gestation. Students explore autism and engage in research on the causes of autism through problem- based learning and a Web Quest. They will create an informational brochure based on their research findings. My Environment, My Health, My Choices 1 © 2006, University of Rochester May be copied for classroom use Table of Contents Pre/Post Test 3-4 Pre/Post Test Answer Key 5-6 Learning Context 7 Procedure 8 Instructions for Implementing the Problem-Based Learning Activity 9 PBL Chart 10 Problem-Based Learning Activity 11-14 WebQuest 15-16 Informational Brochure 17 New York State Learning Standards 18 Teachers, we would appreciate your feedback. Please complete our brief, online Environmental Health Science Activity Evaluation Survey after you implement these lessons in your classroom. The survey is available online at: www.surveymonkey.com/s.asp?u=502132677711 My Environment, My Health, My Choices 2 © 2006, University of Rochester May be copied for classroom use (Student Pre/Post Test) Name _________________________________ Class _____ 1. Autism is most likely caused by 1. poor parenting when a child is young 2. a specific environmental chemical 3. poor nutrition 4. the exact cause of autism in not yet known 2. Some scientists believe that autism results from changes in the “brain stem” that are caused by gene mutations in the HOXA 1 gene. -

REVIEW ARTICLE the Genetics of Autism

REVIEW ARTICLE The Genetics of Autism Rebecca Muhle, BA*; Stephanie V. Trentacoste, BA*; and Isabelle Rapin, MD‡ ABSTRACT. Autism is a complex, behaviorally de- tribution of a few well characterized X-linked disorders, fined, static disorder of the immature brain that is of male-to-male transmission in a number of families rules great concern to the practicing pediatrician because of an out X-linkage as the prevailing mode of inheritance. The astonishing 556% reported increase in pediatric preva- recurrence rate in siblings of affected children is ϳ2% to lence between 1991 and 1997, to a prevalence higher than 8%, much higher than the prevalence rate in the general that of spina bifida, cancer, or Down syndrome. This population but much lower than in single-gene diseases. jump is probably attributable to heightened awareness Twin studies reported 60% concordance for classic au- and changing diagnostic criteria rather than to new en- tism in monozygotic (MZ) twins versus 0 in dizygotic vironmental influences. Autism is not a disease but a (DZ) twins, the higher MZ concordance attesting to ge- syndrome with multiple nongenetic and genetic causes. netic inheritance as the predominant causative agent. By autism (the autistic spectrum disorders [ASDs]), we Reevaluation for a broader autistic phenotype that in- mean the wide spectrum of developmental disorders cluded communication and social disorders increased characterized by impairments in 3 behavioral domains: 1) concordance remarkably from 60% to 92% in MZ twins social interaction; 2) language, communication, and and from 0% to 10% in DZ pairs. This suggests that imaginative play; and 3) range of interests and activities. -

Evidence-Based Interventions for Autism Spectrum Disorders

Evidence-Based Interventions for Autism Spectrum Disorders Scott Lindgren, Ph.D. Alissa Doobay, Ph.D. May 2011 This research was completed for the Iowa Department of Human Services by the Center for Disabilities and Development of the University of Iowa Children’s Hospital. The views expressed are the independent products of university research and do not necessarily represent the views of the Iowa Department of Human Services or The University of Iowa. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE ………………………………………………………………………………… 3 DEFINING AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDERS (ASD) ……………………………... 4 ASSESSMENT OF AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDERS ……………………………... 6 INTERVENTIONS FOR AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDERS .……………………… 9 Need for Evidence-Based Interventions ……………………………………… 9 Identifying Effective Interventions …………………………………………… 9 Basic Principles of Effective Early Intervention …………………………….. 10 Research on ASD Interventions ………………………………………………. 11 Interventions Supported by Significant Scientific Evidence ……………….. 12 Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) …………………………….……….… 12 Early Intensive Interventions ………………………………...…………... 14 Social Skills Training ……………………………………………………... 14 Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy ……………………………………...…….. 15 Medication ……………………………………………………………....... 15 Other Evidence-Based Interventions ……………………………………... 16 Interventions with Promising or Emerging Evidence ………………………. 17 Interventions with Limited Scientific Evidence ……………………………… 17 Interventions that are Not Recommended ……………………..…………….. 20 Using these Findings for Treatment Planning ……………………………….. 20 SUMMARY -

Epidemiology Report of Autism in California

Report to the Legislature on the Principal Findings from The Epidemiology of Autism in California: A Comprehensive Pilot Study IN CALIFORNIA AUTISM M.I.N.D. Institute University of California, Davis October 17, 2002 THE EPIDEMIOLOGY OF UC Davis Project Staff: ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Robert S. Byrd, M.D., M.P.H. Principal Investigator Allyson C. Sage, R.N., M.P.H. Project Manager Janet Keyzer, R.N.C., M.P.A. Lead Chart Abstractor Rachel Shefelbine Research Assistant/ADI-R Administrator Kasie Gee, M.P.H. Research Assistant Kristen Enders Administrative Assistant Jonathan Neufeld, Ph.D. Clinical Psychologist Nhue Do Post Graduate Researcher/ADI-R Administrator Kelly Heung, M.S. Post Graduate Researcher/ADI-R Administrator IN CALIFORNIA Tiffany Hughes Post Graduate Researcher Ruth Baron, R.N. Chart Abstractor Andrea Moore, M.S.W. Chart Abstractor Bonnie Walbridge, R.N., M.P.H. Chart Abstractor/ADI-R Administrator Steven Samuels, Ph.D. Statistical Consultant Daniel Tancredi, M.S. Statistical Consultant Jingsong He, M.S. Statistician Emma Calvert Student Assistant Diana Chavez Student Assistant Anna Elsdon Student Assistant Lolly Lee Student Assistant Denise Wong Student Assistant UCLA Site Project Staff: ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ AUTISM Marian Sigman, Ph.D. Co-Investigator Michael Bono, Ph.D. Co-Investigator Caitlin Beck Project Manager/ADI-R Administrator Sara Clavell Research Assistant/ADI-R Administrator Elizabeth Lizaola Research Assistant/ADI-R Administrator Vera Meyerkova Research Assistant/ADI-R Administrator THE EPIDEMIOLOGY -

Understanding Autism

Introduction As a parent, you may have many questions regarding diagnosis. As you look for answers, you may encounter information about autism, its causes, and possible treatments. All of these different opinions can make it challenging for a family to organize options and begin to choose a treatment plan that best fits the family. We hope that this packet will help better prepare you to understand the information you receive about treatments for autism, as well as give you the chance to look over the most recent professional opinions about autism. Westside Regional Center anticipates supporting your family as you proceed from your lifetime. What is Autism? How and why did my child develop autism Unfortunately, no apparent cause exists for most cases, but most experts believe that autism is primarily a genetic condition. For about 10% of cases, experts believe that autism has either a specific genetic (from parent to child) or environmental cause. For example, there is an increased risk for autism from specific genetic disorders such as Fragile X Syndrome, Angelman Syndrome, Tuberous Sclerosis, Rh untreated Phenylketonuria, and some chromosome abnormalities. Known environmental causes include taking thalidomide during pregnancy (a type of sedative now not routinely available in the United States) or having German measles (rubella) during pregnancy. There are three main behaviors that are found in all children with autism: 1. Difficulty with social interaction: Children with autism may not be able to relate easily to people, have a hard time playing with other children, or have certain behaviors, such as avoiding eye contact or making socially inappropriate gestures in conversation. -

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) Fact Sheet

Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) What are autism spectrum Importance of Early Diagnosis disorders? Because autism is a genetic disorder, there is Autism spectrum disorders (ASD) are a no single treatment or medication that can group of “cure” it. There is no blood testing that will developmental diagnose an ASD. disabilities caused Autism appears to have its roots in very by a problem with early brain development. It is important to the brain. learn the signs and act early. The earlier you Scientists do not get help, the better for your child. know yet exactly what causes this problem. ASD can Early Signs of Autism impact a person’s Spectrum Disorders functioning at different levels, from very mild to severely. Social Differences There is usually nothing about how a child with autism looks that sets them apart from ▪ Resists snuggling when picked up; other children, but they may communicate, stiffens back instead interact, behave, and learn in ways that are ▪ Makes little or no eye contact different from most children. ▪ Shows no or less expression in response to parent’s smile or other It is estimated that 1 in 59 children have facial expressions been identified with an autism spectrum ▪ No or less pointing to objects or events disorder (ASD). Boys are five times more to get parents to look at them likely to be affected than girls. ASD occurs in ▪ Less likely to bring objects to show to all racial, ethnic and socioeconomic parents just to share his interest groups. Autism affects each individual in a ▪ Less likely to show appropriate facial different way – with varying degrees of expressions severity – this is a “spectrum disorder.” ▪ Difficulty in recognizing what others might be thinking or feeling by looking Causes of Autism at their facial expressions ▪ Less likely to show concern (empathy) There may be many different factors that for others make a child more likely to have an ASD, including environmental, biologic and genetic factors. -

Autism: Symptoms, Causes, and Treatments

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work Spring 5-2007 Autism: Symptoms, Causes, and Treatments Susan Elizabeth Sapp University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Recommended Citation Sapp, Susan Elizabeth, "Autism: Symptoms, Causes, and Treatments" (2007). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/1111 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Autism 1 Running head: AUTISM Susan Eliza beth Sapp Bachelor of Arts Autism: Symptoms, Causes, and Treatments Susan Sapp University of Tennessee - Knoxville Autism 2 Introduction Waiting in a restaurant, the anxious Charlie is amazed when his younger brother, Raymond, almost instantaneously counts the number of spilled toothpicks on the floor after a waitress drops the box. With skepticism, Charlie tells Raymond he is wrong because Charlie counted 246 toothpicks on the floor, but the box contained 250 toothpicks. Both and waitress and Charlie are in disbelief when the waitress realizes 4 toothpicks are left in the box. This example is one of many examples of the capabilities of an autistic savant. Making a public debut in the movie, Rain Man, the effects of autism were made available to a wide audience across the world. -

Brief Note on Autism Therapies and Treatment Andrew Cooper * Behavioural Issues That Are Common in People with Autism

OPEN ACCESS Freely available online Autism–Open Access Perspective 2021 Brief Note on Autism Therapies and Treatment Andrew Cooper * behavioural issues that are common in people with autism. Some programmes emphasise the reduction of problem habits Child Psychiatrist, Oxford University, University Section and the acquisition of new skills. Some services teach children of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Park Hospital for how to behave in social environments or how to interact more Children, Old Road, Headington, Oxford OX3 7LQ, UK effectively with others. Applied behaviour analysis (ABA) may assist children in learning new skills and transferring them to INTRODUCTION other situations. The term Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) refers to a Educational therapies continuum of neuro developmental disorders. Communication and social contact issues are common in these disorders. Highly structured training services also work well for children Limited, repeated, and stereotyped interests or patterns of with autism spectrum disorder. A team of experts and a number behaviour are common in people with ASD. Symptoms of of activities to develop social skills, communication, and autism usually appear between the ages of 12 and 24 months in attitudes are usually used in successful initiatives. Preschoolers early childhood. Symptoms, on the other hand, can occur who undergo comprehensive, individualised behavioural sooner or later. A significant delay in language or social growth therapies also make significant gains. can be one of the first signs. Family therapies Causes of Autism Parents and other family members should learn to play and Finding a close relative who suffers from autism, communicate with their children in ways that foster social fragile X syndrome, or other genetic conditions interaction skills, handle problem behaviours, and teach Being the child of older parents everyday life skills and communication to their children. -

The Role of Intestinal Flora in Autism and Nutritional Approaches

Demiroglu Science University Florence Nightingale Journal of Transplantation2020;5(1-2):61-69 doi: 10.5606/dsufnjt.2020.017 The role of intestinal flora in autism and nutritional approaches Aslı Melike Ekmekçi1, Oytun Erbaş1,2 1Institute of Experimental Medicine, Gebze-Kocaeli, Turkey 2Department of Physiology, Medical Faculty of Demiroğlu Bilim University, Istanbul, Turkey ABSTRACT Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a social behavior disorder and awareness on ASD has been increasing nowadays. Social deficiencies and repetitive movements constitute the symptoms of ASD occurring in childhood. As there is no biological marker in autism, parental and clinician approaches are based on diagnosis. Genetic and environmental factors play a role in autism, and its prevalence has been increasing in recent years. The process and amount of exposure to environmental factors create differences in the cause of autism. Although it is unclear yet whether autism is a cause or result, impaired intestinal flora is among the symptoms of autism. Factors such as nutrition approaches and perinatal factors have been thought to play a role in intestinal flora dysbiosis. Metabolites that cross the blood-brain barrier in the intestinal flora dysbiosis can cause morphological changes in the hippocampus in the brain. Various dietary approaches and fecal microbiota transplantation have become candidates for autism treatment methods to improve the deteriorated flora. In this review, we discuss the effects of therapeutic nutritional approaches and fecal transplantation by examining the relationship between ASD and intestinal flora. Keywords: Autism spectrum disorder, intestinal flora, nutrition Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a behavioral are heavy metals, antibiotics and chemical disorder characterized by language and social toxic substances.