Autism Spectrum Disorders: Selected Readings and Resources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neural Signatures of Autism

Neural signatures of autism Martha D. Kaisera, Caitlin M. Hudaca, Sarah Shultza,b, Su Mei Leea,b, Celeste Cheunga, Allison M. Berkena, Ben Deena, Naomi B. Pitskela, Daniel R. Sugruea, Avery C. Voosa, Celine A. Saulniera, Pamela Ventolaa, Julie M. Wolfa, Ami Klina, Brent C. Vander Wyka, and Kevin A. Pelphreya,b,1 aYale Child Study Center, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT 06520, and bDepartment of Psychology, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06520 Edited by Dale Purves, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC, and approved October 13, 2010 (received for review July 19, 2010) Functional magnetic resonance imaging of brain responses to bi- well illustrated by the discovery that point-light displays (i.e., vid- ological motion in children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), eos created by placing lights on the major joints of a person and unaffected siblings (US) of children with ASD, and typically devel- filming them moving in the dark), although relatively impov- oping (TD) children has revealed three types of neural signatures: (i) erished stimuli, contain sufficient information to identify the kind state activity, related to the state of having ASD that characterizes of motion being produced (e.g., walking, dancing, reaching), as the nature of disruption in brain circuitry; (ii) trait activity, reflecting well as the identity of the agent (8). Visual sensitivity to biological shared areas of dysfunction in US and children with ASD, thereby motion is an evolutionarily well-conserved and ontogenetically providing a promising neuroendophenotype to facilitate efforts to early-emerging mechanism that is fundamental to adaptive social bridge genomic complexity and disorder heterogeneity; and (iii) engagement (9); for example, newly hatched chicks recognize bi- compensatory activity, unique to US, suggesting a neural system– ological motion in point-light displays (10), and 2-d-old human level mechanism by which US might compensate for an increased infants preferentially attend to biological motion in point-light genetic risk for developing ASD. -

Brain Disorder and Rock Art

Brain Disorder and Rock Art Brain Disorder and Rock Art Robert G. Bednarik Prompted by numerous endeavours to link a variety of brain illnesses/conditions with the introduction of palaeoart, especially rock art, the author reviews these proposals in the light of the causes of these psychiatric conditions. Several of these proposals are linked to the assumption that palaeoart was introduced through shamanism. It is demonstrated that there is no simplistic link between shamanism and brain disorders, although it is possible that some of the relevant susceptibility alleles might be involved in some shamanic experiences. Similarly, no connection between rock art and shamanism has been credibly demonstrated. Moreover, the time frame applied in all these hypotheses is fallacious for several reasons. These notions are all based on the belief that palaeoart was introduced by ‘anatomically modern humans’ and on the replacement hypothesis. Finally, the assumption that neuropathologies and shamanism preceded the advent of palaeoart is also suspect. These numerous speculations derive from neglect of the relevant empirical factors, be they archaeological or neurological. This article owes a great deal to a recent paper by review the epistemological issues that lead to the for- Bullen (2011), critiquing the attribution of rock art mulation of such opinions by rock-art commentators. to bipolar disorder, and the subsequent elaboration Having elsewhere dealt in some detail with the by Helvenston (2012a) and Bullen’s (2012) response first of Whitley’s crucial propositions, that shamans (see below for details). This author is in agreement introduced palaeoart, the author will examine the with most of the points made in that discussion, so topic of the origins of what is simplistically termed this is not to present counterpoints or to canvas any ‘artistic production’ — ‘palaeoart’ would be a better substantive disagreements, but to follow Helvenston’s word for the phenomenon in question because it is example and expand the scope of the discussion. -

Iacc Strategic Plan for Autism Spectrum Disorder 2018-2019 Update

INTERAGENCY AUTISM COORDINATING COMMITTEE strategic plan for autism spectrum disorder 2018-2019 update INTERAGENCY AUTISM COORDINATING COMMITTEE strategic plan for autism spectrum disorder 2018-2019 update IACC STRATEGIC PLAN FOR AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDER 2018-2019 UPDATE COVER DESIGN Medical Arts Branch, Office of Research Services, National Institutes of Health COPYRIGHT INFORMATION This report is a Work of the United States Government. A suggested citation follows. SUGGESTED CITATION Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee (IACC). IACC Strategic Plan for Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) 2018-2019 Update. July 2020. Retrieved from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee website: http://iacc.hhs.gov/strategic-plan/2019/. II IACC STRATEGIC PLAN FOR AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDER 2018-2019 UPDATE TABLE OF CONTENTS About the IACC.................................................................................................................................................................................................. IV Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................................................................... VI Chapter 1: Highlights from IACC Full Committee Meetings 2018-2019............................................................................................. X Chapter 2: IACC Working Group Activities: Improving Health Outcomes for Individuals on the Autism Spectrum -

Autism Practice Parameters

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry AACAP is pleased to offer Practice Parameters as soon as they are approved by the AACAP Council, but prior to their publication in the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (JAACAP). This article may be revised during the JAACAP copyediting, author query, and proof reading processes. Any final changes in the document will be made at the time of print publication and will be reflected in the final electronic version of the Practice Parameter. AACAP and JAACAP, and its respective employees, are not responsible or liable for the use of any such inaccurate or misleading data, opinion, or information contained in this iteration of this Practice Parameter. PRACTICE PARAMETER FOR THE ASSESSMENT AND TREATMENT OF CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS WITH AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDER ABSTRACT Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is characterized by patterns of delay and deviance in the development of social, communicative, and cognitive skills which arise in the first years of life. Although frequently associated with intellectual disability, this condition is distinctive in terms of its course, impact, and treatment. ASD has a wide range of syndrome expression and its management presents particular challenges for clinicians. Individuals with an ASD can present for clinical care at any point in development. The multiple developmental and behavioral problems associated with this condition necessitate multidisciplinary care, coordination of services, and advocacy for individuals and their families. Early, sustained intervention and the use of multiple treatment modalities are indicated. Key Words: autism, practice parameters, guidelines, developmental disorders, pervasive developmental disorders. ATTRIBUTION This parameter was developed by Fred Volkmar, M.D., Matthew Siegel, M.D., Marc Woodbury-Smith, M.D., Bryan King, M.D., James McCracken, M.D., Matthew State, M.D., Ph.D. -

HHS Announces Appointment of New Membership and New Chair for the Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee

For Immediate Release Contact: Office of Autism Research Coordination/NIH October 28, 2015 E-mail: [email protected] HHS Announces Appointment of New Membership and New Chair for the Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) today announced the appointments of new and returning members to the Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee (IACC), reauthorized under the Autism CARES Act. After an open call for nominations for members of the public to serve on the committee, Secretary of Health and Human Services, Sylvia M. Burwell, appointed this group of individuals to provide her with advice to advance research, strengthen services, and increase opportunities for people on the autism spectrum. The public member appointees include three adults on the autism spectrum, several family members of children and adults on the autism spectrum, clinicians, researchers, and leaders of national autism research, services, and advocacy organizations. Many of the appointed individuals serve dual roles, dedicating their professional careers to helping people on the autism spectrum because of their personal experiences with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). The first meeting of the new committee will take place on November 17, 2015 in Rockville, Maryland. In addition to the new public members, the IACC will have a new chair when it reconvenes. Dr. Thomas Insel, who served as the Director of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and as Chair of the committee for more than a decade, announced his planned departure for Google Life Sciences in at the end of October 2015. Dr. Bruce Cuthbert, who will become Acting Director of NIMH on November 1, has been appointed to serve as the IACC Chair over the next year. -

May 9-12 Rotterdam Netherlands

2018 ANNUAL MEETING MAY 9-12 ROTTERDAM NETHERLANDS PROGRAM BOOK www.autism-insar.org INSAR 2018 Sponsors We thank the following organizations for their generous support of the INSAR Annual Meeting. Platinum Sponsor Level Gold Sponsor Level Silver Sponsor Level Autism Science Foundation Hilibrand Foundation Nancy Lurie Marks Family Foundation TABLE OF CONTENTS Sponsorship .................................Inside Front Cover TABLE OF CONTENTS Special Interest Groups Schedule .......................... 6 Speaker Ready Room ............................................ 6 De Doelen Floor Plans ........................................ 7-9 Meeting Information Schedule-At-A-Glance .................................... 10-12 In-Conjunction Events .................................... 13-14 Keynote Speakers .............................................. 15 Awardees ..................................................... 16-19 INSAR MISSION Acknowledgments .......................................... 20-21 STATEMENT To promote the highest quality INSAR Summer Institute .................................... 22 research in order to improve the Abstract Author Index ...................................... 134 lives of people affected by autism. General Information .......................................... 208 Exhibitors ....................................................... 210 Strategic Initiatives Setting the Bar: Increase the quality, AM diversity and relevance of research promoted through annual meetings, journal, Keynote Address ............................................... -

Overview of Biomedical Treatments Presentation

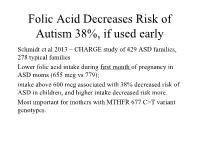

Folic Acid Decreases Risk of Autism 38%, if used early Schmidt et al 2013 – CHARGE study of 429 ASD families, 278 typical families Lower folic acid intake during first month of pregnancy in ASD moms (655 mcg vs 779); intake above 600 mcg associated with 38% decreased risk of ASD in children, and higher intake decreased risk more. Most important for mothers with MTHFR 677 C>T variant genotypes. Folic Acid decreases risk of ASD if taken near conception (cont.) Suren et al 2013 – study of 85,176 Norwegian children, including 270 with ASD. In children whose mothers took folic acid (400 mcg) between 4 weeks prior to conception to 8 weeks after conception, 0.10% (64/61 042) had autistic disorder, compared with 0.21% (50/24 134) in those unexposed to folic acid. 39% lower risk of ASD in those who took prenatal folic acid (400 mcg); Little benefit if taken after 8 weeks Overview of Dietary, Nutritional, and Medical Treatments for Autism James B. Adams, Ph.D. President’s Professor, Arizona State University President, Autism Society of Greater Phoenix President, Autism Nutrition Research Center Chair of Scientific Advisory Board, Neurological Health Foundation Father of a daughter with autism http://autism.asu.edu Our research group is dedicated to finding the causes of autism, how to prevent autism, and how to best help people with autism. Nutrition: vitamins, minerals, fatty acids, amino acids Metabolism: glutathione, methylation, sulfation, oxidative stress Mitochondria – ATP, muscle strength, carnitine Toxic Metals and Chelation Gastrointestinal -

Measuring the Effectiveness of Play As an Intervention to Support

Measuring the Effectiveness of Play as an Intervention to Support Language Development in Young Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Hierarchically- Modeled Meta-Analysis by Gregory V. Boerio Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Education in the Educational Leadership Program Youngstown State University May, 2021 Measuring the Effectiveness of Play as an Intervention to Support Language Development in Young Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Hierarchically- Modeled Meta-Analysis Gregory V. Boerio I hereby release this dissertation to the public. I understand that this dissertation will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: _______________________________________________________________ Gregory V. Boerio, Student Date Approvals: _______________________________________________________________ Dr. Karen H. Larwin, Dissertation Chair Date _______________________________________________________________ Dr. Patrick T. Spearman, Committee Member Date _______________________________________________________________ Dr. Carrie R. Jackson, Committee Member Date _______________________________________________________________ Dr. Matthew J. Erickson, Committee Member Date _______________________________________________________________ Dr. Salvatore A. Sanders, Dean of Graduate Studies Date ii © G. Boerio 2021 iii Abstract The purpose of the current investigation is to analyze extant research examining the impact of play therapy on the development of language skills in young children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). As rates of ASD diagnoses continue to increase, families and educators are faced with making critical decisions regarding the selection and implementation of evidence-based practices or therapies, including play-based interventions, to support the developing child as early as 18 months of age. -

Placental Trophoblast Inclusions in Autism Spectrum Disorder George M

Placental Trophoblast Inclusions in Autism Spectrum Disorder George M. Anderson, Andrea Jacobs-Stannard, Katarzyna Chawarska, Fred R. Volkmar, and Harvey J. Kliman Background: Microscopic examination of placental tissue may provide a route to assessing risk and understanding underlying biology of autism. Methods: Occurrence of a distinctive microscopic placental morphological abnormality, the trophoblast inclusion, was assessed using archived placental tissue. The rate of occurrence of trophoblast inclusion-positive slides observed for 13 individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) was compared to the rate in an anonymous consecutive birth cohort. Results: The occurrence of inclusion positive slides was significantly greater in the ASD group compared to the control group (6/27 slides, 22.2% vs. 12/154, 7.8%; Fisher Exact Test, two-tailed p ϭ .033; relative risk 2.85). The proportion of positive cases was also greater in the ASD group (5/13 cases, 38.5% vs. 8/61, 13.1%; Fisher Exact, two-tailed p ϭ .044; relative risk 2.93). Behavioral severity scores did not differ across groups of inclusion positive (N ϭ 4) and negative (N ϭ 8) ASD individuals. Conclusions: Although probably not functionally detrimental or causative, the greater occurrence of placental trophoblast inclusions observed in ASD individuals may reflect altered early developmental processes. Further research is required to replicate the basic finding, to understand the basis for the trophoblastic abnormality, and to determine the utility of the measure in early detection of ASD. Key Words: Autism, early screening, marker, placenta, trophoblast, genes, and in early screening or risk assessment. Although most trophoblast inclusion measurable biological phenotypes are expected to be multi- determined, they may actually offer advantages in reflecting win and family studies have provided convincing evi- convergent processes related to neurobiological abnormality. -

The Paradox of Giftedness and Autism Packet of Information for Professionals (PIP) – Revised (2008)

The Connie Belin & Jacqueline N. Blank International Center for Gifted Education and Talent Development The University of Iowa College of Education The Paradox of Giftedness and Autism Packet of Information for Professionals (PIP) – Revised (2008) Susan G. Assouline Megan Foley Nicpon Nicholas Colangelo Matthew O’Brien The Paradox of Giftedness and Autism The University of Iowa Belin-Blank Center The Paradox of Giftedness and Autism Packet of Information for Professionals (PIP) – Revised (2008) This Packet of Information (PIP) was originally developed in 2007 for the Student Program Faculty and Professional Staff of the Belin-Blank Center for Gifted Education and Talent Development (B-BC). It has been revised and expanded to incorporate multiple forms of special gifted programs including academic year Saturday programs, which can be both enrichment or accelerative; non-residential summer programs; and residential summer programs. Susan G. Assouline, Megan Foley Nicpon, Nicholas Colangelo, Matthew O’Brien We acknowledge the Messengers of Healing Winds Foundation for its support in the creation of this information packet. We acknowledge the students and families who participated in the Belin-Blank Center’s Assessment and Counseling Clinic. Their patience with the B-BC staff and their dedication to the project was critical to the development of the recommendations that comprise this Packet of Information for Professionals. © 2008, The University of Iowa Belin-Blank Center. All rights reserved. This publication, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form without written permission of the authors. The Paradox of Giftedness and Autism Purpose Structure of PIP This Packet of Information for Professionals (PIP) Section I of PIP introduces general information related to both giftedness was developed for professionals who work with and autism spectrum disorders. -

Environmental and Genetic Factors in Autism Spectrum Disorders: Special Emphasis on Data from Arabian Studies

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Review Environmental and Genetic Factors in Autism Spectrum Disorders: Special Emphasis on Data from Arabian Studies Noor B. Almandil 1,† , Deem N. Alkuroud 2,†, Sayed AbdulAzeez 2, Abdulla AlSulaiman 3, Abdelhamid Elaissari 4 and J. Francis Borgio 2,* 1 Department of Clinical Pharmacy Research, Institute for Research and Medical Consultation (IRMC), Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, Dammam 31441, Saudi Arabia; [email protected] 2 Department of Genetic Research, Institute for Research and Medical Consultation (IRMC), Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, Dammam 31441, Saudi Arabia; [email protected] (D.N.A.); [email protected] (S.A.) 3 Department of Neurology, College of Medicine, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, Dammam 31441, Saudi Arabia; [email protected] or [email protected] 4 Univ Lyon, University Claude Bernard Lyon-1, CNRS, LAGEP-UMR 5007, F-69622 Lyon, France; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel.: +966-13-333-0864 † These authors contributed equally to this work. Received: 26 January 2019; Accepted: 19 February 2019; Published: 23 February 2019 Abstract: One of the most common neurodevelopmental disorders worldwide is autism spectrum disorder (ASD), which is characterized by language delay, impaired communication interactions, and repetitive patterns of behavior caused by environmental and genetic factors. This review aims to provide a comprehensive survey of recently published literature on ASD and especially novel insights into excitatory synaptic transmission. Even though numerous genes have been discovered that play roles in ASD, a good understanding of the pathophysiologic process of ASD is still lacking. -

The Joy of Autism: Part 2

However, even autistic individuals who are profoundly disabled eventually gain the ability to communicate effectively, and to learn, and to reason about their behaviour and about effective ways to exercise control over their environment, their unique individual aspects of autism that go beyond the physiology of autism and the source of the profound intrinsic disabilities will come to light. These aspects of autism involve how they think, how they feel, how they express their sensory preferences and aesthetic sensibilities, and how they experience the world around them. Those aspects of individuality must be accorded the same degree of respect and the same validity of meaning as they would be in a non autistic individual rather than be written off, as they all too often are, as the meaningless products of a monolithically bad affliction." Based on these extremes -- the disabling factors and atypical individuality, Phil says, they are more so disabling because society devalues the atypical aspects and fails to accommodate the disabling ones. That my friends, is what we are working towards -- a place where the group we seek to "help," we listen to. We do not get offended when we are corrected by the group. We are the parents. We have a duty to listen because one day, our children may be the same people correcting others tomorrow. In closing, about assumptions, I post the article written by Ann MacDonald a few days ago in the Seattle Post Intelligencer: By ANNE MCDONALD GUEST COLUMNIST Three years ago, a 6-year-old Seattle girl called Ashley, who had severe disabilities, was, at her parents' request, given a medical treatment called "growth attenuation" to prevent her growing.