The Paradox of Giftedness and Autism Packet of Information for Professionals (PIP) – Revised (2008)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Life and Times Of'asperger's Syndrome': a Bakhtinian Analysis Of

The life and times of ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’: A Bakhtinian analysis of discourses and identities in sociocultural context Kim Davies Bachelor of Education (Honours 1st Class) (UQ) Graduate Diploma of Teaching (Primary) (QUT) Bachelor of Social Work (UQ) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2015 The School of Education 1 Abstract This thesis is an examination of the sociocultural history of ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’ in a Global North context. I use Bakhtin’s theories (1919-21; 1922-24/1977-78; 1929a; 1929b; 1935; 1936-38; 1961; 1968; 1970; 1973), specifically of language and subjectivity, to analyse several different but interconnected cultural artefacts that relate to ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’ and exemplify its discursive construction at significant points in its history, dealt with chronologically. These sociocultural artefacts are various but include the transcript of a diagnostic interview which resulted in the diagnosis of a young boy with ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’; discussion board posts to an Asperger’s Syndrome community website; the carnivalistic treatment of ‘neurotypicality’ at the parodic website The Institute for the Study of the Neurologically Typical as well as media statements from the American Psychiatric Association in 2013 announcing the removal of Asperger’s Syndrome from the latest edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-5 (APA, 2013). One advantage of a Bakhtinian framework is that it ties the personal and the sociocultural together, as inextricable and necessarily co-constitutive. In this way, the various cultural artefacts are examined to shed light on ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’ at both personal and sociocultural levels, simultaneously. -

Brain Disorder and Rock Art

Brain Disorder and Rock Art Brain Disorder and Rock Art Robert G. Bednarik Prompted by numerous endeavours to link a variety of brain illnesses/conditions with the introduction of palaeoart, especially rock art, the author reviews these proposals in the light of the causes of these psychiatric conditions. Several of these proposals are linked to the assumption that palaeoart was introduced through shamanism. It is demonstrated that there is no simplistic link between shamanism and brain disorders, although it is possible that some of the relevant susceptibility alleles might be involved in some shamanic experiences. Similarly, no connection between rock art and shamanism has been credibly demonstrated. Moreover, the time frame applied in all these hypotheses is fallacious for several reasons. These notions are all based on the belief that palaeoart was introduced by ‘anatomically modern humans’ and on the replacement hypothesis. Finally, the assumption that neuropathologies and shamanism preceded the advent of palaeoart is also suspect. These numerous speculations derive from neglect of the relevant empirical factors, be they archaeological or neurological. This article owes a great deal to a recent paper by review the epistemological issues that lead to the for- Bullen (2011), critiquing the attribution of rock art mulation of such opinions by rock-art commentators. to bipolar disorder, and the subsequent elaboration Having elsewhere dealt in some detail with the by Helvenston (2012a) and Bullen’s (2012) response first of Whitley’s crucial propositions, that shamans (see below for details). This author is in agreement introduced palaeoart, the author will examine the with most of the points made in that discussion, so topic of the origins of what is simplistically termed this is not to present counterpoints or to canvas any ‘artistic production’ — ‘palaeoart’ would be a better substantive disagreements, but to follow Helvenston’s word for the phenomenon in question because it is example and expand the scope of the discussion. -

Sprawozdanie Z Działalności Fundacji Ditero Za Rok 2017

FUNDACJA DITERO WOLIMIERZ 18 59-814 POBIEDNA [email protected] Wolimierz, 30.06.2018 Sprawozdanie z działalności Fundacji Ditero za rok 2017 Wprowadzenie Fundacja została powołana aktem notarialnym w dniu 3 lutego 2016 r. W Krajowym Rejestrze Sądowym została zarejestrowana w dniu 12 maja 2016 r. W lipcu 2016 została uruchomiona pracownia terapeutyczna, działająca w ramach podstawowej działalności Fundacji. W roku 2017 działania Fundacji rozwinęły się na nowe obszary związane z pozaszkolnymi formami edukacji oraz kulturą i sportem. Władze Zarząd: Agnieszka Surmacz (Prezes) Rada Fundacji: Danuta Łopuch, Wiktoria Wiktorczyk Rada Nadzorcza: Kaja Pachulska, Aneta Mykietyszyn Cele statutowe organizacji Cele Fundacji zostały szczegółowo opisane w rozdziale II statutu Fundacji. Najważniejsze cele realizowane w 2017 r to: 1. Wspieranie osób niepełnosprawnych i ich rodzin poprzez świadczenie usług diagnostycznych i terapeutycznych, 2. Upowszechnianie i ochrona praw dziecka, praca z osobami mającymi kontakt z dziećmi z niepełnosprawnościami i dysfunkcjami rozwojowymi, 3. Działalność charytatywna, promocja i organizacja wolontariatu na rzecz rodzin z dziećmi z niepełnosprawnościami. 4. Działalności na rzecz organizacji pozarządowych oraz innych podmiotów aktywnych w sferze publicznej, mających cele zbieżne celami Fundacji. 5. Realizacja zadań z zakresu kultury, edukacji sportowej dzieci i młodzieży; Sposób realizacji celów statutowych organizacji Fundacja realizowała swoje cele przede wszystkim poprzez: • realizację usług terapeutycznych (prowadzenie -

Research Participation and Employment for Autistic Individuals in Library and Information Science: a Review of the Literature Nancy Everhart & Amelia M

Research Participation and Employment for Autistic Individuals in Library and Information Science: A Review of the Literature Nancy Everhart & Amelia M. Anderson Abstract Autism prevalence is growing, and autistic people themselves are important in the library and information science field, both as library patrons and employees. Including them in all stages of research about the neurodivergent experience is valuable, and their input and participation is increasingly used in technology research, particularly usability studies. Neurodivergent persons also have unique abilities that align with a wide array of information professions and accommodations can be made that allow them to thrive in the workplace. It is critical that meaningful involvement of autistic individuals is a component of making policy at all levels. Introduction The population of individuals diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) has grown, but current literature regarding autistic adults lacks first-person accounts, particularly in the information environment. Adult voices have been drowned out by the overwhelming emphasis, both in the general public and the scholarly literature, on early identification and intervention for young children with autism (Cox et al. 2017). Much research on college students with ASD also focuses on the perspective of the professor or instructor, not the students themselves (Barnhill 2014). Achieving a representative sample is vital to the validity of social research findings, particularly when findings are used as evidence to inform social policies and programs. Likewise, autistic individuals often seek employment in information settings such as libraries and computer technology. This paper discusses the involvement of persons with ASD in library and information research and employment more broadly, and also specifically within the context of several recent studies. -

Becoming Autistic: How Do Late Diagnosed Autistic People

Becoming Autistic: How do Late Diagnosed Autistic People Assigned Female at Birth Understand, Discuss and Create their Gender Identity through the Discourses of Autism? Emily Violet Maddox Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Sociology and Social Policy September 2019 1 Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................................................... 5 ABSTRACT ....................................................................................................................................................... 6 ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................................................. 7 CHAPTER ONE ................................................................................................................................................. 8 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................. 8 1.1 RESEARCH OBJECTIVES ........................................................................................................................................ 8 1.2 TERMINOLOGY ................................................................................................................................................ 14 1.3 OUTLINE OF CHAPTERS .................................................................................................................................... -

Book Project Chapters 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Pages Format

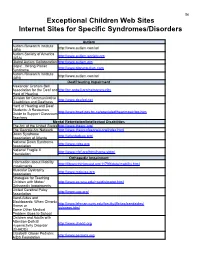

56 Exceptional Children Web Sites Internet Sites for Specific Syndromes/Disorders Autism Autism Research Institute http://www.autism.com/ari (ARI) Autism Society of America http://www.autism-society.org (ASA) Global Autism Collaboration http://www.autism.org Oops!...Wrong Planet http://www.planetautism.com Syndrome Autism Research Institute http://www.autism.com/ari (ARI) Deaf/Hearing Impairment Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf and http://nc.agbell.org/netcommunity Hard of Hearing Division for Communicative http://www.deafed.net Disabilities and Deafness Hard of Hearing and Deaf Students: A Resources http://www.bced.gov.bc.ca/specialed/hearimpair/toc.htm Guide to Support Classroom Teachers Mental Retardation/Intellectual Disabilities The Arc of the United States http://www.thearc.org/ The Georgia Arc Network http://www.thearcofgeorgia.org/index.html Down Syndrome http://atlantadsaa.org/ Association of Atlanta National Down Syndrome http://www.ndss.org Association National Fragile X http://www.nfxf.org/html/home.shtml Foundation Orthopedic Impairment Information about Mobility http://library.thinkquest.org/11799/data/mobility.html Impairments Muscular Dystrophy http://www.mdausa.org Association Strategies for Teaching Children with Motor/ http://www.as.wvu.edu/~scidis/motor.html Orthopedic Impairments United Cerebral Palsy http://www.ucp.org/ Association Band-Aides and Blackboards: When Chronic http://www.lehman.cuny.edu/faculty/jfleitas/bandaides/ Illness or sickness.html Some Other Medical Problem Goes to School Children -

The Impact of a Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder on Nonmedical Treatment Options in the Learning Environment from the Perspectives of Parents and Pediatricians

St. John Fisher College Fisher Digital Publications Education Doctoral Ralph C. Wilson, Jr. School of Education 12-2017 The Impact of a Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder on Nonmedical Treatment Options in the Learning Environment from the Perspectives of Parents and Pediatricians Cecilia Scott-Croff St. John Fisher College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/education_etd Part of the Education Commons How has open access to Fisher Digital Publications benefited ou?y Recommended Citation Scott-Croff, Cecilia, "The Impact of a Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder on Nonmedical Treatment Options in the Learning Environment from the Perspectives of Parents and Pediatricians" (2017). Education Doctoral. Paper 341. Please note that the Recommended Citation provides general citation information and may not be appropriate for your discipline. To receive help in creating a citation based on your discipline, please visit http://libguides.sjfc.edu/citations. This document is posted at https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/education_etd/341 and is brought to you for free and open access by Fisher Digital Publications at St. John Fisher College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Impact of a Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder on Nonmedical Treatment Options in the Learning Environment from the Perspectives of Parents and Pediatricians Abstract The purpose of this qualitative study was to identify the impact of a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder on treatment options available, within the learning environment, at the onset of a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) from the perspective of parents and pediatricians. Utilizing a qualitative methodology to identify codes, themes, and sub-themes through semi-structured interviews, the research captures the lived experiences of five parents with children on the autism spectrum and five pediatricians who cared for those children and families. -

The Joy of Autism: Part 2

However, even autistic individuals who are profoundly disabled eventually gain the ability to communicate effectively, and to learn, and to reason about their behaviour and about effective ways to exercise control over their environment, their unique individual aspects of autism that go beyond the physiology of autism and the source of the profound intrinsic disabilities will come to light. These aspects of autism involve how they think, how they feel, how they express their sensory preferences and aesthetic sensibilities, and how they experience the world around them. Those aspects of individuality must be accorded the same degree of respect and the same validity of meaning as they would be in a non autistic individual rather than be written off, as they all too often are, as the meaningless products of a monolithically bad affliction." Based on these extremes -- the disabling factors and atypical individuality, Phil says, they are more so disabling because society devalues the atypical aspects and fails to accommodate the disabling ones. That my friends, is what we are working towards -- a place where the group we seek to "help," we listen to. We do not get offended when we are corrected by the group. We are the parents. We have a duty to listen because one day, our children may be the same people correcting others tomorrow. In closing, about assumptions, I post the article written by Ann MacDonald a few days ago in the Seattle Post Intelligencer: By ANNE MCDONALD GUEST COLUMNIST Three years ago, a 6-year-old Seattle girl called Ashley, who had severe disabilities, was, at her parents' request, given a medical treatment called "growth attenuation" to prevent her growing. -

Support Systems for Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder During

Support Systems for Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder during their Transition to Higher Education: A Qualitative Analysis of Online Discussions Amelia Anderson, Bradley Cox, Jeffrey Edelstein, and Abigail Wolz Abstract This study explored how college students with autism identify and use support systems during the transition to higher education. This study explored how these students described their experiences within an online environment among their peers. The study used unobtrusive qualitative methods to collect and analyze data from online forum discussion posts from Wrong Planet, an online forum for people with autism. Students found their support systems in various ways. Many report using services provided by their Office of Disability Services, but students must be aware that these services exist first, and often must have a diagnosis to receive such supports. This study makes suggestions for higher education institutions to identify and promote their support services, both those that are accessible through Offices of Disability Services, and those that are available without diagnosis or disclosure. Research Questions Discussion The students clearly believe that the burden is on them to seek help. How do students with ASD describe their experiences with support systems during their Whether by registering with the disability services office, or searching the transition to college? school’s website, or by otherwise exploring what the college or university has - Who or what are the support systems that college students with ASD describe? to offer, these students describe it as being up to them to discover their own - How do college students with ASD find these support systems? support systems. -

CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY Growing up with ASD (Autism Spectrum

Psychology in Russia: State of the Art Russian Lomonosov Psychological Moscow State Volume 12, Issue 3, 2019 Society University CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY Growing Up with ASD (Autism Spectrum Disorder): Directions and Methods of Psychological Intervention Igor A. Kostin* Federal State Budget Scientifc Institution “Institute of Special Education of the Russian Academy of Education”, Moscow, Russia * Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Background. Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a lifelong pervasive develop- Keywords: mental disorder afecting subjects’ emotions, will, and cognition, and inhibiting ASD (autism their social adaptation. spectrum Objective. To defne directions and methods for psychological assistance to disorder); autistic people that would let them achieve higher self-actualization and inde- qualitative pendence, and avoid social maladaptation. longitudinal Design. Te following methods were used: analysis of the life histories and search; social catamneses of autistic individuals; participant observation of their behavior; maladaptation; analysis of materials (text summaries) of psychological consulting with families social who have autistic members; analysis of materials from remedial sessions with environment; people with autism and developmental disorders. psychological Research participants were autistic individuals age 12 years or more at the remediation beginning and up to 38–40 years at the end. Results. Te long-term manifestations of autistic development in emotions, will, and cognition are described. Tese manifestations afect subjects’ adapta- tion and independence negatively, even in cases of remarkable progress. Two important aspects of psychological assistance are: a) mastering of skills; and b) improving comprehension of social relationships, one’s own psychologi- cal world, and other people’s minds. Te author proposes some methods of psy- chological remedial work and insists that rules for social interaction should not be learned mechanically. -

Student Research Report Mother Blaming; Or Autism, Gender and Science

66 Student research report Mother blaming; or autism, gender and science HILARY STACE Introduction My PhD ‘Moving beyond love and luck; building right relationships and respecting lived expe- rience in New Zealand autism policy’ suggests that good outcomes for autism are dependent on having family to advocate and luck that they will be able to find services and supportive peo- ple. But, we could improve autism policy if we worked with the experts, people with autism. My interest in this topic arose from having an autistic son who now has a job and a full social life, but he’s still autistic. When researching autism the meme of the ‘refrigerator mother’ and other mother blaming assumptions are difficult to avoid. Why is this? Autism: contested meanings Autism was named in 1943 (Kanner, 1943, p. 53). The latest descriptions in the pyschiatrists’ bible the DSM IV TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) consider it to be a triad of im- pairments: in communication (none or inappropriate use of language), in understanding others (mind-blindness or lack of empathy) and imagination (replaced by obsessive special interests). It is now considered a wide spectrum from the non-verbal, intellectually impaired, cut-off per- son to the highly articulate and intelligent people such as Einstein (Attwood, 2009). People with autism describe the condition differently. They often use the term neurotypical for non-autistic people and neurodiverse to encompass alternatives such as autism. They usual- ly describe problems with understanding and predicting neurotypical peoples’ actions and be- haviour, particularly their non-verbal cues, and often report sensory sensitivities to such things as sound, touch or taste. -

Rethinking Our Approach to Fostering Language and Social Development, Matt Braun

2/24/2017 Rethinking our Approach in Introduction Schools and the Community: Taking a Strengths Based • Who am I? Approach to Fostering Language and Social Development • Who are you? • What are we doing here today? Matt Braun, PhD, L/CCC-SLP Speech Language Pathologist Owner- Speech & Language Solutions, LLC Getting Started Our Goal To reiterate some of the common themes we’ve heard through the Evaluate the evidence. conference: Evaluate our practice. From the folks at Notre Dame (ACE)- Welcome, Serve, Celebrate Create a culture of Inclusivity in our schools and communities (define How can we make changes? communities) What’s our plan to make those changes? This is a Journey….It takes time….but what are we doing to promote inclusivity in my school and community See Handout Overview Traditional approaches • Review Traditional Models of Practice Medical model and Subsequently, More Traditional Models of Practice • Introduce Strengths Bases Practices • Focusses on what is wrong, broken, or needs “fixing” • Review theory and evidence for Strengths Based Practices • In general physical health, something (a system, organ, bone, muscle, etc.) is • How to apply strengths based practices in the classroom broken, hurt, weakened, etc. • Questions/Comments/Discussion • Moving in to more social sciences we’ve tried and tried to apply this same model • Speaking in this way suggests that the problem lies within the person and implies that something is wrong or broken inferring there is something to fix (Saleebey, 2009) 1 2/24/2017 Traditional vs. Strengths Based The Evolution of Family Centered Approaches to Care Care and Strengths Based Practices • Traditional deficit based approaches aim to fix what is broken or support a disability.