Building Community Among Autistic Adults DISSERTATION Submitted In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Life and Times Of'asperger's Syndrome': a Bakhtinian Analysis Of

The life and times of ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’: A Bakhtinian analysis of discourses and identities in sociocultural context Kim Davies Bachelor of Education (Honours 1st Class) (UQ) Graduate Diploma of Teaching (Primary) (QUT) Bachelor of Social Work (UQ) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2015 The School of Education 1 Abstract This thesis is an examination of the sociocultural history of ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’ in a Global North context. I use Bakhtin’s theories (1919-21; 1922-24/1977-78; 1929a; 1929b; 1935; 1936-38; 1961; 1968; 1970; 1973), specifically of language and subjectivity, to analyse several different but interconnected cultural artefacts that relate to ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’ and exemplify its discursive construction at significant points in its history, dealt with chronologically. These sociocultural artefacts are various but include the transcript of a diagnostic interview which resulted in the diagnosis of a young boy with ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’; discussion board posts to an Asperger’s Syndrome community website; the carnivalistic treatment of ‘neurotypicality’ at the parodic website The Institute for the Study of the Neurologically Typical as well as media statements from the American Psychiatric Association in 2013 announcing the removal of Asperger’s Syndrome from the latest edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-5 (APA, 2013). One advantage of a Bakhtinian framework is that it ties the personal and the sociocultural together, as inextricable and necessarily co-constitutive. In this way, the various cultural artefacts are examined to shed light on ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’ at both personal and sociocultural levels, simultaneously. -

Sprawozdanie Z Działalności Fundacji Ditero Za Rok 2017

FUNDACJA DITERO WOLIMIERZ 18 59-814 POBIEDNA [email protected] Wolimierz, 30.06.2018 Sprawozdanie z działalności Fundacji Ditero za rok 2017 Wprowadzenie Fundacja została powołana aktem notarialnym w dniu 3 lutego 2016 r. W Krajowym Rejestrze Sądowym została zarejestrowana w dniu 12 maja 2016 r. W lipcu 2016 została uruchomiona pracownia terapeutyczna, działająca w ramach podstawowej działalności Fundacji. W roku 2017 działania Fundacji rozwinęły się na nowe obszary związane z pozaszkolnymi formami edukacji oraz kulturą i sportem. Władze Zarząd: Agnieszka Surmacz (Prezes) Rada Fundacji: Danuta Łopuch, Wiktoria Wiktorczyk Rada Nadzorcza: Kaja Pachulska, Aneta Mykietyszyn Cele statutowe organizacji Cele Fundacji zostały szczegółowo opisane w rozdziale II statutu Fundacji. Najważniejsze cele realizowane w 2017 r to: 1. Wspieranie osób niepełnosprawnych i ich rodzin poprzez świadczenie usług diagnostycznych i terapeutycznych, 2. Upowszechnianie i ochrona praw dziecka, praca z osobami mającymi kontakt z dziećmi z niepełnosprawnościami i dysfunkcjami rozwojowymi, 3. Działalność charytatywna, promocja i organizacja wolontariatu na rzecz rodzin z dziećmi z niepełnosprawnościami. 4. Działalności na rzecz organizacji pozarządowych oraz innych podmiotów aktywnych w sferze publicznej, mających cele zbieżne celami Fundacji. 5. Realizacja zadań z zakresu kultury, edukacji sportowej dzieci i młodzieży; Sposób realizacji celów statutowych organizacji Fundacja realizowała swoje cele przede wszystkim poprzez: • realizację usług terapeutycznych (prowadzenie -

Research Participation and Employment for Autistic Individuals in Library and Information Science: a Review of the Literature Nancy Everhart & Amelia M

Research Participation and Employment for Autistic Individuals in Library and Information Science: A Review of the Literature Nancy Everhart & Amelia M. Anderson Abstract Autism prevalence is growing, and autistic people themselves are important in the library and information science field, both as library patrons and employees. Including them in all stages of research about the neurodivergent experience is valuable, and their input and participation is increasingly used in technology research, particularly usability studies. Neurodivergent persons also have unique abilities that align with a wide array of information professions and accommodations can be made that allow them to thrive in the workplace. It is critical that meaningful involvement of autistic individuals is a component of making policy at all levels. Introduction The population of individuals diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) has grown, but current literature regarding autistic adults lacks first-person accounts, particularly in the information environment. Adult voices have been drowned out by the overwhelming emphasis, both in the general public and the scholarly literature, on early identification and intervention for young children with autism (Cox et al. 2017). Much research on college students with ASD also focuses on the perspective of the professor or instructor, not the students themselves (Barnhill 2014). Achieving a representative sample is vital to the validity of social research findings, particularly when findings are used as evidence to inform social policies and programs. Likewise, autistic individuals often seek employment in information settings such as libraries and computer technology. This paper discusses the involvement of persons with ASD in library and information research and employment more broadly, and also specifically within the context of several recent studies. -

Becoming Autistic: How Do Late Diagnosed Autistic People

Becoming Autistic: How do Late Diagnosed Autistic People Assigned Female at Birth Understand, Discuss and Create their Gender Identity through the Discourses of Autism? Emily Violet Maddox Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Sociology and Social Policy September 2019 1 Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................................................... 5 ABSTRACT ....................................................................................................................................................... 6 ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................................................. 7 CHAPTER ONE ................................................................................................................................................. 8 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................. 8 1.1 RESEARCH OBJECTIVES ........................................................................................................................................ 8 1.2 TERMINOLOGY ................................................................................................................................................ 14 1.3 OUTLINE OF CHAPTERS .................................................................................................................................... -

Girls on the Autism Spectrum

GIRLS ON THE AUTISM SPECTRUM Girls are typically diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders at a later age than boys and may be less likely to be diagnosed at an early age. They may present as shy or dependent on others rather than disruptive like boys. They are less likely to behave aggressively and tend to be passive or withdrawn. Girls can appear to be socially competent as they copy other girls’ behaviours and are often taken under the wing of other nurturing friends. The need to fit in is more important to girls than boys, so they will find ways to disguise their difficulties. Like boys, girls can have obsessive special interests, but they are more likely to be typical female topics such as horses, pop stars or TV programmes/celebrities, and the depth and intensity of them will be less noticeable as unusual at first. Girls are more likely to respond to non-verbal communication such as gestures, pointing or gaze-following as they tend to be more focused and less prone to distraction than boys. Anxiety and depression are often worse in girls than boys especially as their difference becomes more noticeable as they approach adolescence. This is when they may struggle with social chat and appropriate small-talk, or the complex world of young girls’ friendships and being part of the in-crowd. There are books available that help support the learning of social skills aimed at both girls and boys such as The Asperkid’s Secret Book of Social Rules, by Jennifer Cook O’Toole and Asperger’s Rules: How to make sense of school and friends, by Blythe Grossberg. -

The Paradox of Giftedness and Autism Packet of Information for Professionals (PIP) – Revised (2008)

The Connie Belin & Jacqueline N. Blank International Center for Gifted Education and Talent Development The University of Iowa College of Education The Paradox of Giftedness and Autism Packet of Information for Professionals (PIP) – Revised (2008) Susan G. Assouline Megan Foley Nicpon Nicholas Colangelo Matthew O’Brien The Paradox of Giftedness and Autism The University of Iowa Belin-Blank Center The Paradox of Giftedness and Autism Packet of Information for Professionals (PIP) – Revised (2008) This Packet of Information (PIP) was originally developed in 2007 for the Student Program Faculty and Professional Staff of the Belin-Blank Center for Gifted Education and Talent Development (B-BC). It has been revised and expanded to incorporate multiple forms of special gifted programs including academic year Saturday programs, which can be both enrichment or accelerative; non-residential summer programs; and residential summer programs. Susan G. Assouline, Megan Foley Nicpon, Nicholas Colangelo, Matthew O’Brien We acknowledge the Messengers of Healing Winds Foundation for its support in the creation of this information packet. We acknowledge the students and families who participated in the Belin-Blank Center’s Assessment and Counseling Clinic. Their patience with the B-BC staff and their dedication to the project was critical to the development of the recommendations that comprise this Packet of Information for Professionals. © 2008, The University of Iowa Belin-Blank Center. All rights reserved. This publication, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form without written permission of the authors. The Paradox of Giftedness and Autism Purpose Structure of PIP This Packet of Information for Professionals (PIP) Section I of PIP introduces general information related to both giftedness was developed for professionals who work with and autism spectrum disorders. -

Women and Western Culture 1 GWS

GWS 200: Women and Western Culture Feminist and LGBTQ Anthropological Approaches to “Women” and “the West” Spring 2015 Class: Monday, Wednesday, and Friday Office Hours: Tuesday 9:00-9:50am 4:00-5:00pm and by appointment Education Building, Room #318 Bentley’s House of Coffee & Tea 1730 E. Speedway Blvd Instructor: Erin L. Durban-Albrecht Email: [email protected] Email Policy: Emails from students will be returned within 48 hours; however, emails sent between 5pm Friday and 8am Monday will be treated as if sent on Monday morning. You will need to plan ahead in order to get questions to me in a timely manner. In terms of email etiquette, include GWS 200 in the subject line along with the topic of your email. Please remember that in this context email is a means of formal, professional communication. Course Description: GWS 200 is an introductory course to Gender and Women’s Studies featuring selected works of critical feminist scholarship on the production and position of women in the West. This is a Tier 2- Humanities General Education course that also fulfills the University of Arizona Diversity Emphasis requirement. This particular course approaches the topics of “women” and “the West” from an anthropological perspective that thinks about questions of culture in relationship to history, place and space, and political economy. We will concentrate in the realm of feminist anthropology, which is attentive to power and the production of social difference in terms of gender, sex, sexuality, race, nation, economic class, and (dis)ability. Feminist anthropology has strong connections to the field of queer anthropology, influenced by the growth in lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (LGBT) studies in the academy. -

Why We Play: an Anthropological Study (Enlarged Edition)

ROBERTE HAMAYON WHY WE PLAY An Anthropological Study translated by damien simon foreword by michael puett ON KINGS DAVID GRAEBER & MARSHALL SAHLINS WHY WE PLAY Hau BOOKS Executive Editor Giovanni da Col Managing Editor Sean M. Dowdy Editorial Board Anne-Christine Taylor Carlos Fausto Danilyn Rutherford Ilana Gershon Jason Troop Joel Robbins Jonathan Parry Michael Lempert Stephan Palmié www.haubooks.com WHY WE PLAY AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL STUDY Roberte Hamayon Enlarged Edition Translated by Damien Simon Foreword by Michael Puett Hau Books Chicago English Translation © 2016 Hau Books and Roberte Hamayon Original French Edition, Jouer: Une Étude Anthropologique, © 2012 Éditions La Découverte Cover Image: Detail of M. C. Escher’s (1898–1972), “Te Encounter,” © May 1944, 13 7/16 x 18 5/16 in. (34.1 x 46.5 cm) sheet: 16 x 21 7/8 in. (40.6 x 55.6 cm), Lithograph. Cover and layout design: Sheehan Moore Typesetting: Prepress Plus (www.prepressplus.in) ISBN: 978-0-9861325-6-8 LCCN: 2016902726 Hau Books Chicago Distribution Center 11030 S. Langley Chicago, IL 60628 www.haubooks.com Hau Books is marketed and distributed by Te University of Chicago Press. www.press.uchicago.edu Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Table of Contents Acknowledgments xiii Foreword: “In praise of play” by Michael Puett xv Introduction: “Playing”: A bundle of paradoxes 1 Chronicle of evidence 2 Outline of my approach 6 PART I: FROM GAMES TO PLAY 1. Can play be an object of research? 13 Contemporary anthropology’s curious lack of interest 15 Upstream and downstream 18 Transversal notions 18 First axis: Sport as a regulated activity 18 Second axis: Ritual as an interactional structure 20 Toward cognitive studies 23 From child psychology as a cognitive structure 24 . -

2019 CATALOG Dear Friend

Over 20 Years of Excellence in Autism Publishing 2019 CATALOG Dear Friend, Future Horizons was created to meet the needs of teachers, therapists, and family members who face the challenge of autism. Our books, videos, and conferences bring you the most current information possible to aid in that challenge. It is our strong belief that every child and adult with autism can improve and contribute to the lives of those who love them and, just as importantly, contribute to society. We at Future Horizons pride ourselves in bringing to the mission not only a strong sense of professionalism, but one that is based on personal relationships. All of us have family members or friends who are affected. Future Horizons would not exist today without two very special men. The first is my brother, Alex, whom I had the pleasure of growing up with as I watched him develop into FROM THE PUBLISHER THE FROM a fine young man. Alex was a light that lit up lives wherever he went. Whether working with TEACCH in North Carolina, speaking at conferences, attending Alex Gilpin family gatherings he enjoyed so much, or working in the jobs he held, his delightful sense of humor, courtesy, and caring improved the lives of all who knew him. You could not help but smile back at his infectious grin and I never heard him say an unkind word about anyone. Alex is the genesis for this company. My father, R. Wayne Gilpin, was the man who brought the company to life. After writing the book inspired by Alex, Laughing and Loving with Au- tism, he found other materials that needed a good publisher. -

Book Project Chapters 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Pages Format

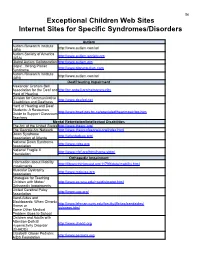

56 Exceptional Children Web Sites Internet Sites for Specific Syndromes/Disorders Autism Autism Research Institute http://www.autism.com/ari (ARI) Autism Society of America http://www.autism-society.org (ASA) Global Autism Collaboration http://www.autism.org Oops!...Wrong Planet http://www.planetautism.com Syndrome Autism Research Institute http://www.autism.com/ari (ARI) Deaf/Hearing Impairment Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf and http://nc.agbell.org/netcommunity Hard of Hearing Division for Communicative http://www.deafed.net Disabilities and Deafness Hard of Hearing and Deaf Students: A Resources http://www.bced.gov.bc.ca/specialed/hearimpair/toc.htm Guide to Support Classroom Teachers Mental Retardation/Intellectual Disabilities The Arc of the United States http://www.thearc.org/ The Georgia Arc Network http://www.thearcofgeorgia.org/index.html Down Syndrome http://atlantadsaa.org/ Association of Atlanta National Down Syndrome http://www.ndss.org Association National Fragile X http://www.nfxf.org/html/home.shtml Foundation Orthopedic Impairment Information about Mobility http://library.thinkquest.org/11799/data/mobility.html Impairments Muscular Dystrophy http://www.mdausa.org Association Strategies for Teaching Children with Motor/ http://www.as.wvu.edu/~scidis/motor.html Orthopedic Impairments United Cerebral Palsy http://www.ucp.org/ Association Band-Aides and Blackboards: When Chronic http://www.lehman.cuny.edu/faculty/jfleitas/bandaides/ Illness or sickness.html Some Other Medical Problem Goes to School Children -

People with Autism Spectrum Disorder in the Workplace: an Expanding Legal Frontier

\\jciprod01\productn\H\HLC\52-1\HLC105.txt unknown Seq: 1 23-JAN-17 10:48 People with Autism Spectrum Disorder in the Workplace: An Expanding Legal Frontier Wendy F. Hensel1 Over the past two decades, there has been a significant increase in the number of children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Recent estimates suggest that ASD may affect as many as one out of every 68 children in the United States, an increase of over 78% since 2007. Although some of this increase can be attributed to the enhanced awareness and focus on early inter- vention resulting from public education campaigns, much of the cause remains unknown. Nearly half of all individuals diagnosed with ASD possess either average or above average intelligence, but only a small percentage are employed, regard- less of their level of educational attainment or individual qualifications. One study of adults with high functioning autism identified employment “as the single biggest issue or barrier facing them.” In the next eight years alone, experts predict a 230% increase in the num- ber of young people with ASD transitioning to adulthood. As these numbers grow, there inevitably will be pressure to change the status quo and expand employment opportunities for them. At the same time, as a result of the amend- ments to the Americans with Disabilities Act, litigants of all disabilities are in- creasingly successful in establishing coverage under the statute and increasing protection against disability discrimination in employment. Taken together, there is little doubt that increasing numbers of individuals with ASD will enter the labor pool over the next decade. -

Support Systems for Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder During

Support Systems for Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder during their Transition to Higher Education: A Qualitative Analysis of Online Discussions Amelia Anderson, Bradley Cox, Jeffrey Edelstein, and Abigail Wolz Abstract This study explored how college students with autism identify and use support systems during the transition to higher education. This study explored how these students described their experiences within an online environment among their peers. The study used unobtrusive qualitative methods to collect and analyze data from online forum discussion posts from Wrong Planet, an online forum for people with autism. Students found their support systems in various ways. Many report using services provided by their Office of Disability Services, but students must be aware that these services exist first, and often must have a diagnosis to receive such supports. This study makes suggestions for higher education institutions to identify and promote their support services, both those that are accessible through Offices of Disability Services, and those that are available without diagnosis or disclosure. Research Questions Discussion The students clearly believe that the burden is on them to seek help. How do students with ASD describe their experiences with support systems during their Whether by registering with the disability services office, or searching the transition to college? school’s website, or by otherwise exploring what the college or university has - Who or what are the support systems that college students with ASD describe? to offer, these students describe it as being up to them to discover their own - How do college students with ASD find these support systems? support systems.