Women with High Functioning ASD: Relationships and Sexual Health

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Life and Times Of'asperger's Syndrome': a Bakhtinian Analysis Of

The life and times of ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’: A Bakhtinian analysis of discourses and identities in sociocultural context Kim Davies Bachelor of Education (Honours 1st Class) (UQ) Graduate Diploma of Teaching (Primary) (QUT) Bachelor of Social Work (UQ) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2015 The School of Education 1 Abstract This thesis is an examination of the sociocultural history of ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’ in a Global North context. I use Bakhtin’s theories (1919-21; 1922-24/1977-78; 1929a; 1929b; 1935; 1936-38; 1961; 1968; 1970; 1973), specifically of language and subjectivity, to analyse several different but interconnected cultural artefacts that relate to ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’ and exemplify its discursive construction at significant points in its history, dealt with chronologically. These sociocultural artefacts are various but include the transcript of a diagnostic interview which resulted in the diagnosis of a young boy with ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’; discussion board posts to an Asperger’s Syndrome community website; the carnivalistic treatment of ‘neurotypicality’ at the parodic website The Institute for the Study of the Neurologically Typical as well as media statements from the American Psychiatric Association in 2013 announcing the removal of Asperger’s Syndrome from the latest edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-5 (APA, 2013). One advantage of a Bakhtinian framework is that it ties the personal and the sociocultural together, as inextricable and necessarily co-constitutive. In this way, the various cultural artefacts are examined to shed light on ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’ at both personal and sociocultural levels, simultaneously. -

Sprawozdanie Z Działalności Fundacji Ditero Za Rok 2017

FUNDACJA DITERO WOLIMIERZ 18 59-814 POBIEDNA [email protected] Wolimierz, 30.06.2018 Sprawozdanie z działalności Fundacji Ditero za rok 2017 Wprowadzenie Fundacja została powołana aktem notarialnym w dniu 3 lutego 2016 r. W Krajowym Rejestrze Sądowym została zarejestrowana w dniu 12 maja 2016 r. W lipcu 2016 została uruchomiona pracownia terapeutyczna, działająca w ramach podstawowej działalności Fundacji. W roku 2017 działania Fundacji rozwinęły się na nowe obszary związane z pozaszkolnymi formami edukacji oraz kulturą i sportem. Władze Zarząd: Agnieszka Surmacz (Prezes) Rada Fundacji: Danuta Łopuch, Wiktoria Wiktorczyk Rada Nadzorcza: Kaja Pachulska, Aneta Mykietyszyn Cele statutowe organizacji Cele Fundacji zostały szczegółowo opisane w rozdziale II statutu Fundacji. Najważniejsze cele realizowane w 2017 r to: 1. Wspieranie osób niepełnosprawnych i ich rodzin poprzez świadczenie usług diagnostycznych i terapeutycznych, 2. Upowszechnianie i ochrona praw dziecka, praca z osobami mającymi kontakt z dziećmi z niepełnosprawnościami i dysfunkcjami rozwojowymi, 3. Działalność charytatywna, promocja i organizacja wolontariatu na rzecz rodzin z dziećmi z niepełnosprawnościami. 4. Działalności na rzecz organizacji pozarządowych oraz innych podmiotów aktywnych w sferze publicznej, mających cele zbieżne celami Fundacji. 5. Realizacja zadań z zakresu kultury, edukacji sportowej dzieci i młodzieży; Sposób realizacji celów statutowych organizacji Fundacja realizowała swoje cele przede wszystkim poprzez: • realizację usług terapeutycznych (prowadzenie -

The Effects and Feasibility of Using Tiered Instruction to Increase Conversational Turn Taking for Preschoolers with and Without Disabilities

THE EFFECTS AND FEASIBILITY OF USING TIERED INSTRUCTION TO INCREASE CONVERSATIONAL TURN TAKING FOR PRESCHOOLERS WITH AND WITHOUT DISABILITIES A dissertation submitted to the Kent State University College and Graduate School of Education, Health, and Human Services in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Sandra Hess Robbins May 2013 © Copyright, 2013 by Sandra Hess Robbins All Rights Reserved ii A dissertation written by Sandra Hess Robbins B.S.Ed., University of Wisconsin, Oshkosh, 2002 M.Ed., Kent State University, 2006 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2013 Approved by ____________________, Co-director, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Kristie Pretti-Frontcak ____________________, Co-director, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Sanna Harjusola-Webb ____________________, Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Christine Balan ____________________, Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Richard Cowan Accepted by ____________________, Director, School of Lifespan Development and Educational Mary Dellman-Jenkins Sciences ____________________, Dean, College of Education, Health, and Human Services Daniel F. Mahony iii ROBBINS, SANDRA HESS, Ph.D., May 2013 Lifespan Development and Educational Sciences THE EFFECTS AND FEASIBILITY OF USING TIERED INSTRUCTION TO INCREASE CONVERSATIONAL TURN TAKING FOR PRESCHOOLERS WITH AND WITHOUT DISABILITIES (282 pp.) Co-Directors of Dissertation: Kristie Pretti-Frontczak, Ph.D. Sanna Harjusola-Webb, Ph.D. The purpose of the study was to examine the effectiveness and feasibility of using tiered instruction to increase the frequency of conversational turn taking (CTT) among preschoolers with and without disabilities in an inclusive setting. Three CTT interventions (Universal Design for Learning, Peer Mediated Instruction, and Milieu Teaching) were organized on a hierarchy of intensity and implemented in an additive manner. -

Research Participation and Employment for Autistic Individuals in Library and Information Science: a Review of the Literature Nancy Everhart & Amelia M

Research Participation and Employment for Autistic Individuals in Library and Information Science: A Review of the Literature Nancy Everhart & Amelia M. Anderson Abstract Autism prevalence is growing, and autistic people themselves are important in the library and information science field, both as library patrons and employees. Including them in all stages of research about the neurodivergent experience is valuable, and their input and participation is increasingly used in technology research, particularly usability studies. Neurodivergent persons also have unique abilities that align with a wide array of information professions and accommodations can be made that allow them to thrive in the workplace. It is critical that meaningful involvement of autistic individuals is a component of making policy at all levels. Introduction The population of individuals diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) has grown, but current literature regarding autistic adults lacks first-person accounts, particularly in the information environment. Adult voices have been drowned out by the overwhelming emphasis, both in the general public and the scholarly literature, on early identification and intervention for young children with autism (Cox et al. 2017). Much research on college students with ASD also focuses on the perspective of the professor or instructor, not the students themselves (Barnhill 2014). Achieving a representative sample is vital to the validity of social research findings, particularly when findings are used as evidence to inform social policies and programs. Likewise, autistic individuals often seek employment in information settings such as libraries and computer technology. This paper discusses the involvement of persons with ASD in library and information research and employment more broadly, and also specifically within the context of several recent studies. -

Becoming Autistic: How Do Late Diagnosed Autistic People

Becoming Autistic: How do Late Diagnosed Autistic People Assigned Female at Birth Understand, Discuss and Create their Gender Identity through the Discourses of Autism? Emily Violet Maddox Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Sociology and Social Policy September 2019 1 Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................................................... 5 ABSTRACT ....................................................................................................................................................... 6 ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................................................. 7 CHAPTER ONE ................................................................................................................................................. 8 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................. 8 1.1 RESEARCH OBJECTIVES ........................................................................................................................................ 8 1.2 TERMINOLOGY ................................................................................................................................................ 14 1.3 OUTLINE OF CHAPTERS .................................................................................................................................... -

The Paradox of Giftedness and Autism Packet of Information for Professionals (PIP) – Revised (2008)

The Connie Belin & Jacqueline N. Blank International Center for Gifted Education and Talent Development The University of Iowa College of Education The Paradox of Giftedness and Autism Packet of Information for Professionals (PIP) – Revised (2008) Susan G. Assouline Megan Foley Nicpon Nicholas Colangelo Matthew O’Brien The Paradox of Giftedness and Autism The University of Iowa Belin-Blank Center The Paradox of Giftedness and Autism Packet of Information for Professionals (PIP) – Revised (2008) This Packet of Information (PIP) was originally developed in 2007 for the Student Program Faculty and Professional Staff of the Belin-Blank Center for Gifted Education and Talent Development (B-BC). It has been revised and expanded to incorporate multiple forms of special gifted programs including academic year Saturday programs, which can be both enrichment or accelerative; non-residential summer programs; and residential summer programs. Susan G. Assouline, Megan Foley Nicpon, Nicholas Colangelo, Matthew O’Brien We acknowledge the Messengers of Healing Winds Foundation for its support in the creation of this information packet. We acknowledge the students and families who participated in the Belin-Blank Center’s Assessment and Counseling Clinic. Their patience with the B-BC staff and their dedication to the project was critical to the development of the recommendations that comprise this Packet of Information for Professionals. © 2008, The University of Iowa Belin-Blank Center. All rights reserved. This publication, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form without written permission of the authors. The Paradox of Giftedness and Autism Purpose Structure of PIP This Packet of Information for Professionals (PIP) Section I of PIP introduces general information related to both giftedness was developed for professionals who work with and autism spectrum disorders. -

Book Project Chapters 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Pages Format

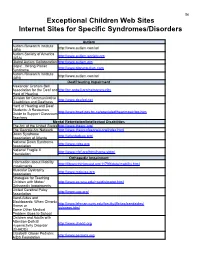

56 Exceptional Children Web Sites Internet Sites for Specific Syndromes/Disorders Autism Autism Research Institute http://www.autism.com/ari (ARI) Autism Society of America http://www.autism-society.org (ASA) Global Autism Collaboration http://www.autism.org Oops!...Wrong Planet http://www.planetautism.com Syndrome Autism Research Institute http://www.autism.com/ari (ARI) Deaf/Hearing Impairment Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf and http://nc.agbell.org/netcommunity Hard of Hearing Division for Communicative http://www.deafed.net Disabilities and Deafness Hard of Hearing and Deaf Students: A Resources http://www.bced.gov.bc.ca/specialed/hearimpair/toc.htm Guide to Support Classroom Teachers Mental Retardation/Intellectual Disabilities The Arc of the United States http://www.thearc.org/ The Georgia Arc Network http://www.thearcofgeorgia.org/index.html Down Syndrome http://atlantadsaa.org/ Association of Atlanta National Down Syndrome http://www.ndss.org Association National Fragile X http://www.nfxf.org/html/home.shtml Foundation Orthopedic Impairment Information about Mobility http://library.thinkquest.org/11799/data/mobility.html Impairments Muscular Dystrophy http://www.mdausa.org Association Strategies for Teaching Children with Motor/ http://www.as.wvu.edu/~scidis/motor.html Orthopedic Impairments United Cerebral Palsy http://www.ucp.org/ Association Band-Aides and Blackboards: When Chronic http://www.lehman.cuny.edu/faculty/jfleitas/bandaides/ Illness or sickness.html Some Other Medical Problem Goes to School Children -

Support Systems for Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder During

Support Systems for Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder during their Transition to Higher Education: A Qualitative Analysis of Online Discussions Amelia Anderson, Bradley Cox, Jeffrey Edelstein, and Abigail Wolz Abstract This study explored how college students with autism identify and use support systems during the transition to higher education. This study explored how these students described their experiences within an online environment among their peers. The study used unobtrusive qualitative methods to collect and analyze data from online forum discussion posts from Wrong Planet, an online forum for people with autism. Students found their support systems in various ways. Many report using services provided by their Office of Disability Services, but students must be aware that these services exist first, and often must have a diagnosis to receive such supports. This study makes suggestions for higher education institutions to identify and promote their support services, both those that are accessible through Offices of Disability Services, and those that are available without diagnosis or disclosure. Research Questions Discussion The students clearly believe that the burden is on them to seek help. How do students with ASD describe their experiences with support systems during their Whether by registering with the disability services office, or searching the transition to college? school’s website, or by otherwise exploring what the college or university has - Who or what are the support systems that college students with ASD describe? to offer, these students describe it as being up to them to discover their own - How do college students with ASD find these support systems? support systems. -

Building Community Among Autistic Adults DISSERTATION Submitted In

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Voices of Belonging: Building Community Among Autistic Adults DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Anthropology by Heather Thomas Dissertation Committee: Associate Professor Keith M. Muprhy, Chair Professor Victoria Bernal Professor Tom Boellstorff 2018 © 2018 Heather Thomas DEDICATION To my mentors, loved ones, and colleagues "Everyone has his or her own way of learning things," he said to himself. "His way isn't the same as mine, nor mine as his. But we're both in search of our Personal Legends, and I respect him for that." Paulo Coelho, The Alchemist ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS v CURRICULUM VITAE vi ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION ix INTRODUCTION 1 Research Problem 3 Background 4 Research Sites 17 Methods 23 CHAPTER 1: Autistic Narrative 28 What Autistic Narratives Do for Autistic Adults 33 Disability Narratives 36 The Spectrum 45 Narrative and Identity Making 50 Group Identification and Disidentification 64 Conclusion 70 CHAPTER 2: Rhetorical Characters of Autisticness 71 Characterizing Autisticness 79 Prospective Members' Goals 81 Diversifying the Autistic Cast 83 Creating an Intersectional Space 105 Conclusion 112 CHAPTER 3: Learning to Be Autistic 109 Autistic Teachers & Autistic Students 121 Lateral Engagements 149 Conclusion: Autistic Proof Spaces 164 CHAPTER 4: Disidentification 158 Labelling & the Reality of a "Disorder" 170 Risky Formerly-Autistic Subjects 179 Countering Certified Autism Experts 183 Anti-Psychiatry in Disidentifiers' Narrative Revisioning 186 Reclassified Neurodivergence 192 Conclusion 199 CONCLUSION 192 iii REFERENCES 199 APPENDIX A: Key Interlocutors & Their Groups 210 APPENDIX B: Glossary 212 iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am deeply grateful for each member of my dissertation committee. -

IMFAR 2010 Disclosure Report *Indicates Presenting Author

IMFAR 2010 Disclosure Report *indicates presenting author Final Name Title Relationships Number 104.005 * R. B. Beaumont The Secret Agent Society: A Multimedia The Social Skills Training Institute: Curriculum for Enhancing the Social Skills of Employment (full or part-time) Children with Asperger's Disorder The Social Skills Training Institute: Receipt of royalties 104.007 R. L. Koegel Type, Function, and Complexity of Koegel Autism Consultants: Ownership or Language Gains in Young Children with partnership Autism Spectrum Disorder Following Behavioral Intervention 104.007 L. K. Koegel Type, Function, and Complexity of Koegel Autism Consultants: Ownership or Language Gains in Young Children with partnership Autism Spectrum Disorder Following Behavioral Intervention 104.008 R. L. Koegel Using the Tools of the Trade: The ADOS as a Koegel Autism Consultants: Ownership or Measure of Treatment Change partnership 104.008 L. K. Koegel Using the Tools of the Trade: The ADOS as a Koegel Autism Consultants: Ownership or Measure of Treatment Change partnership 105.002 A. S. Carter Relationship Between Sensory Over- Alice S. Carter: Receipt of royalties Responsivity and Anxiety in Young Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: 105.007 A. S. Carter Early Sensory Over-Responsivity and Alice S. Carter: Receipt of royalties Affective Symptoms of Children with ASD and Later Family Impairment 105.01 A. M. Wetherby Early Red Flags for Autism Spectrum Author: Other: AW is an author of the Disorders in Toddlers in the Home Early Screening for Autism and Environment Communication Disorders (ESAC) Author: Non-remunerative Brookes Publishing: Other: AW is an author of the Communication and Symbolic Behavior Scales (CSBS) Brookes Publishing: Receipt of royalties 105.011 W. -

(!Congress of Tbe ~Niteb ~Tates ~A~Btngton, Tjb(( 20510

(!Congress of tbe ~niteb ~tates ~a~btngton, tJB(( 20510 August 1, 2016 The Honorable Dr. John King Secretary of Education U.S. Department of Education 400 Maryland Ave., S.W. Washington, DC 20202 Attn: Meredith Miller Re: Notice ofProposed Rulemaking Docket ID ED-2016-0ESE-0032, Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, as Amended by the Every Student Succeeds Act Accountability and State Plans Dear Secretary King: In negotiating the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) with our colleagues, we fought to preserve the Department of Education's (Department) full regulatory authority to promulgate rules and issue guidance. We applaud the Department's notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM) on 34 CFR parts 200 and 299 for balancing ESSA' s strong and clearly articulated federal guardrails with the new law's flexibility for state and local decision-making. The Department's unique role in upholding the civil rights legacy of this law is critical to ensure implementation honors Congressional intent that states and local educational agencies sufficiently support improving outcomes for the nation's disadvantaged students, including through improving equity of educational opportunity. While Congress replaced much of No Child Left Behind (NCLB) with new statutory requirements in ESSA, the new law maintains the historic and bipartisan focus of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) on improving educational outcomes for our nation's disadvantaged students, including low-income students, students of color, students with disabilities, and English learners. In putting forth the proposed regulations, the Department employed its regulatory authority to articulate parameters that will empower states and school districts to use the new flexibility that ESSA affords. -

Autism Organizations Updated 9-21-17

Autism Speaks (US) https://www.autismspeaks.org/ Sponsors autism research and conducts awareness and outreach activities aimed at families, governments, and the public Autism Speaks Canada http://www.autismspeaks.ca/ Autism Society https://www.autism-society.org/ Provides advocacy, education, information and referral, support, and community at national, state and local levels. Autism Science Foundation http://autismsciencefoundation.org/ Mission is to support autism research by providing funding and other assistance to scientists and organizations conducting, facilitating, publicizing and disseminating autism research. Autistic Self Advocacy http://autisticadvocacy.org/ Seeks to advance the Network principles of the disability rights movement with regard to autism. Run by and for autistic people. Autism Research Institute https://www.autism.com/ Mission is to improve the health and well- being of people on the autism spectrum through research and the education of professionals, those who are affected, and their families. Autism Cares Foundation http://autismcaresfoundation.org/ Guiding vision is to enrich the lives of those with autism. Global Autism Project www.globalautismproject.org/ Trains teachers to work with children with autism globally. National Autism Association http://nationalautismassociation.org The leading resource on autism-related wandering prevention and response. Temple Grandin’s Resources http://www.templegrandin.com/ Autistic teacher, animal trainer, author, holds Ph.D Asperger/Autism Network http://www.aane.org/ providing information, education, community, support, and advocacy Asperger 101 https://aspergers101.com/ provide optimum support and expanding opportunities for lifelong growth and fulfillment Spectrum News https://spectrumnews.org/ News and expert opinion on autism research. Autism Citizen https://autismcitizen.org/ Create acceptance of autism through education, public speaking, conferences, etc.