Your Questions: Shaping Future Autism Research Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Working with Students on the Autism Spectrum

Supporting students on the autism spectrum student mentor guidelines By Catriona Mowat, Anna Cooper and Lee Gilson Supporting students on the autism spectrum All rights reserved. No part of this book can be reproduced, stored in a retrievable system or transmitted, in any form or by means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or other wise without the prior permission of the copyright owner. First published by The National Autistic Society 2011 Printed by RAP Spiderweb © The National Autistic Society 2011 Chapters Introduction 3 1. Understanding the autism spectrum 4-9 2. Your role as a student mentor 10-15 3. Getting started 16-23 4. Supporting a student with Asperger syndrome to… 24-29 5. Useful resources 30-33 6. Further reading 34 7. Glossary of terms 35 1 2 Introduction These guidelines were initially prepared as a resource for newly appointed student mentors supporting students with autism and Asperger syndrome at the University of Strathclyde. This guide has been rewritten as a useful resource for any university employing and training its own student mentors, or considering doing so. Readers may reproduce the guidelines, or relevant sections of the guidelines, as long as they acknowledge the source. This new version was made possible by a grant from the Scottish Funding Council in 2009, which has supported not only this publication, but also a research project (led by Charlene Tait of the National Centre for Autism Studies, University of Strathclyde) into transition and retention for students on the autism spectrum, and the delivery of a series of workshops on this topic (jointly delivered by the University of Strathclyde and The National Autistic Society Scotland). -

Autism Europe

N o 5265 June 2016 English Edition Autism - Europe Our campaign: Respect, Acceptance, Inclusion “On the High Seas”: A film to promote the inclusion of children with autism Jon Spiers, Chief Executive of Autistica, on the report denouncing early death among autistic people Adam Bradford, self-advocate and Queen’s Young Leader 2016: “I hope this recognition inspires other young autistic people to reach their goals” Autism-Europe’s 11th International Congress: Keynote speakers announced Published by Autism-Europe Afgiftekantoor - Bureau de dépôt : Brussels - Ed. responsable : Z. Szilvasy For Diversity Autism-Europe aisbl Rue Montoyer, 39 • B - 1000 Brussels, Belgium Tel.:+32-2-675 75 05 - Fax:+32-2-675 72 70 Against Discrimination E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.autismeurope.org SUMMARY Activities - World Autism Awareness Day campaign 2016 ................... 3 - Autism-Europe’s Annual General Assembly 2016 in Cagliari, Italy .............................................................. 7 News & FeAtures - The “On the High Seas” project ....................................... 8 - Premature mortality among persons with autism. Interview with Jon Spiers, Chief Executive of Autistica .................. 10 - App “Oral Health – SOHDEV” improving oral health Dear friends, for people with autism ................................................... 12 It is with great pleasure that we present this latest edition - Interview with Adam Bradford, self-advocate of our LINK magazine, which offers an overview of Autism- and Queen’s Young Leader 2016 ................................... 13 Europe’s recent activities as well as news from a range - Keynotes speakers announced for Autism-Europe’s th of different stakeholders in the world of autism. In this 11 International Congress ........................................... 14 issue, you will be able to get to know our new member - The “Eight Points” project ............................................ -

Summary of Responses by Question

dialoguebydesign making consultation work Adult Autism Strategy consultation A summary of the submissions received in response to the online consultation Prepared for the Department of Health By Dialogue by Design Ltd January 2010 Adult autism consultation summary report – January 2010 Page 1 dialoguebydesign making consultation work Table of contents 1. Executive Summary ...............................................................................................3 2. Introduction ............................................................................................................5 2.1. Background..................................................................................................5 2.2. How the consultation process was managed...............................................5 2.3. Responses...................................................................................................5 2.4. Participation statistics ..................................................................................5 2.5 Reading this summary and interpreting the results......................................9 3. Consultation overview ..........................................................................................10 3.1. Summary of responses to this chapter.......................................................10 3.2. Standard consultation questions ................................................................11 3.7. Easy-read consultation questions ..............................................................26 4. Social -

Overview of Biomedical Treatments Presentation

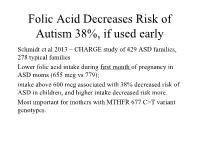

Folic Acid Decreases Risk of Autism 38%, if used early Schmidt et al 2013 – CHARGE study of 429 ASD families, 278 typical families Lower folic acid intake during first month of pregnancy in ASD moms (655 mcg vs 779); intake above 600 mcg associated with 38% decreased risk of ASD in children, and higher intake decreased risk more. Most important for mothers with MTHFR 677 C>T variant genotypes. Folic Acid decreases risk of ASD if taken near conception (cont.) Suren et al 2013 – study of 85,176 Norwegian children, including 270 with ASD. In children whose mothers took folic acid (400 mcg) between 4 weeks prior to conception to 8 weeks after conception, 0.10% (64/61 042) had autistic disorder, compared with 0.21% (50/24 134) in those unexposed to folic acid. 39% lower risk of ASD in those who took prenatal folic acid (400 mcg); Little benefit if taken after 8 weeks Overview of Dietary, Nutritional, and Medical Treatments for Autism James B. Adams, Ph.D. President’s Professor, Arizona State University President, Autism Society of Greater Phoenix President, Autism Nutrition Research Center Chair of Scientific Advisory Board, Neurological Health Foundation Father of a daughter with autism http://autism.asu.edu Our research group is dedicated to finding the causes of autism, how to prevent autism, and how to best help people with autism. Nutrition: vitamins, minerals, fatty acids, amino acids Metabolism: glutathione, methylation, sulfation, oxidative stress Mitochondria – ATP, muscle strength, carnitine Toxic Metals and Chelation Gastrointestinal -

Measuring the Effectiveness of Play As an Intervention to Support

Measuring the Effectiveness of Play as an Intervention to Support Language Development in Young Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Hierarchically- Modeled Meta-Analysis by Gregory V. Boerio Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Education in the Educational Leadership Program Youngstown State University May, 2021 Measuring the Effectiveness of Play as an Intervention to Support Language Development in Young Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Hierarchically- Modeled Meta-Analysis Gregory V. Boerio I hereby release this dissertation to the public. I understand that this dissertation will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: _______________________________________________________________ Gregory V. Boerio, Student Date Approvals: _______________________________________________________________ Dr. Karen H. Larwin, Dissertation Chair Date _______________________________________________________________ Dr. Patrick T. Spearman, Committee Member Date _______________________________________________________________ Dr. Carrie R. Jackson, Committee Member Date _______________________________________________________________ Dr. Matthew J. Erickson, Committee Member Date _______________________________________________________________ Dr. Salvatore A. Sanders, Dean of Graduate Studies Date ii © G. Boerio 2021 iii Abstract The purpose of the current investigation is to analyze extant research examining the impact of play therapy on the development of language skills in young children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). As rates of ASD diagnoses continue to increase, families and educators are faced with making critical decisions regarding the selection and implementation of evidence-based practices or therapies, including play-based interventions, to support the developing child as early as 18 months of age. -

Autism Entangled – Controversies Over Disability, Sexuality, and Gender in Contemporary Culture

Autism Entangled – Controversies over Disability, Sexuality, and Gender in Contemporary Culture Toby Atkinson BA, MA This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Sociology Department, Lancaster University February 2021 1 Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in substantially the same form for the award of a higher degree elsewhere. Furthermore, I declare that the word count of this thesis, 76940 words, does not exceed the permitted maximum. Toby Atkinson February 2021 2 Acknowledgements I want to thank my supervisors Hannah Morgan, Vicky Singleton, and Adrian Mackenzie for the invaluable support they offered throughout the writing of this thesis. I am grateful as well to Celia Roberts and Debra Ferreday for reading earlier drafts of material featured in several chapters. The research was made possible by financial support from Lancaster University and the Economic and Social Research Council. I also want to thank the countless friends, colleagues, and family members who have supported me during the research process over the last four years. 3 Contents DECLARATION ......................................................................................... 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................. 3 ABSTRACT .............................................................................................. 9 PART ONE: ........................................................................................ -

Committee Business

IACC Committee Business IACC Full Committee Meeting April 19, 2018 Susan A. Daniels, Ph.D. Director, Office of Autism Research Coordination Executive Secretary, IACC National Institute of Mental Health Thanks to OARC Staff Susan Daniels, Ph.D. Director Oni Celestin, Ph.D. Julianna Rava, M.P.H. Science Policy Analyst Science Policy Analyst Rebecca Martin, M.P.H Matthew Vilnit, B.S. Public Health Analyst Operations Coordinator Angelice Mitrakas, B.A. Jeff Wiegand, B.S. Management Analyst Web Development Manager Karen Mowrer, Ph.D. Science Policy Analyst April is National Autism Awareness Month NIMH Special Event for Autism Awareness Month The Story Behind Julia, Sesame Street’s Muppet with Autism April 9, 2018 • Panel presentation featuring speakers from Sesame Workshop, the nonprofit educational organization behind Sesame Street • Meet-and-greet with a costumed Julia character Archived video available: https://iacc.hhs.gov/meetings/autism- events/2018/april9/sesame- street.shtml#video Autism Awareness Month News • 2018 Presidential Proclamation: President Donald J. Trump Proclaims April 2, 2018, World Autism Awareness Day • 2018 UN Secretary-General Message: António Guterres' Message on World Autism Awareness Day Autism Awareness Month Events • Autism Awareness Interagency Roundtable Indian Health Service April 2, 2018; Bethesda, MD • Empowering Women and Girls with Autism United Nations April 5, 2018; New York, NY Event page: https://www.un.org/en/events/autismday/ Archived video available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tyhm7p8Gr2A -

Inclusive Practices for Neurodevelopmental Research

Current Developmental Disorders Reports https://doi.org/10.1007/s40474-021-00227-z AUTISM SPECTRUM (A RICHDALE AND LH LAWSON, SECTION EDITORS) Inclusive Practices for Neurodevelopmental Research Sue Fletcher-Watson1 & Kabie Brook2 & Sonny Hallett3 & Fergus Murray3 & Catherine J. Crompton4 Accepted: 9 March 2021 # The Author(s) 2021 Abstract Purpose of Review Inclusive research practice is both a moral obligation and a practical imperative. Here we review its relevance to the study of neurodevelopmental diversity in particular, briefly describing a range of inclusive research models and justifying their use. The review itself is inclusively co-authored with three autistic collaborators and community leaders who all have extensive experience of research involvement. Recent Findings Drawing on theoretical arguments and specific exemplar projects, we describe six key considerations in the delivery of inclusive research. These are the following: taking the first steps towards inclusive practice; setting expectations; community-specific inclusion measures; inclusion and intersectionality; the role of empowerment; and knowledge exchange for inclusion. Together, these sections provide an illustrated guide to the principles and process of inclusive research. Summary Inclusive research practice is both beneficial to and a requirement of excellence in neurodevelopmental research. We call for greater engagement in this participatory research agenda from grant-awarding bodies to facilitate not just inclusive but also emancipatory research. Keywords Participatory research . Inclusion . Neurodiversity . Patient and public involvement . Participation Introduction for its use. We then illustrate six key facets of inclusive re- search in neurodevelopment, drawing on our own experiences What Is Inclusive Research Practice? and including illustrative examples from the literature. Arnstein’s ladder of participation [4•] provides a rudimentary Inclusive research takes place with members of the relevant model for thinking about inclusive research practice. -

Girls on the Autism Spectrum

GIRLS ON THE AUTISM SPECTRUM Girls are typically diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders at a later age than boys and may be less likely to be diagnosed at an early age. They may present as shy or dependent on others rather than disruptive like boys. They are less likely to behave aggressively and tend to be passive or withdrawn. Girls can appear to be socially competent as they copy other girls’ behaviours and are often taken under the wing of other nurturing friends. The need to fit in is more important to girls than boys, so they will find ways to disguise their difficulties. Like boys, girls can have obsessive special interests, but they are more likely to be typical female topics such as horses, pop stars or TV programmes/celebrities, and the depth and intensity of them will be less noticeable as unusual at first. Girls are more likely to respond to non-verbal communication such as gestures, pointing or gaze-following as they tend to be more focused and less prone to distraction than boys. Anxiety and depression are often worse in girls than boys especially as their difference becomes more noticeable as they approach adolescence. This is when they may struggle with social chat and appropriate small-talk, or the complex world of young girls’ friendships and being part of the in-crowd. There are books available that help support the learning of social skills aimed at both girls and boys such as The Asperkid’s Secret Book of Social Rules, by Jennifer Cook O’Toole and Asperger’s Rules: How to make sense of school and friends, by Blythe Grossberg. -

Autism & Faith Resources

AUTISM & FAITH RESOURCES BOOKS: Autism and Spirituality: Psyche, Self, and Spirit in People on the Autism Spectrum Olga Bogdashina The author argues persuasively that the spiritual development of those on the autism spectrum is in fact way ahead of that of their neurotypical peers. She describes differences in sensory perceptual, cognitive and linguistic development that make spiritual and religious experiences come more easily to those on the autism spectrum, and presents a coherent framework for understanding the routes of spiritual development and spiritual intelligence of giftedness within this group. Using research evidence and many real examples to illustrate her hypotheses, she suggests practical ways of supporting the spiritual needs of people on the autism spectrum and their families. Autism and Alleluias Kathleen Deyer Bolduc Almost everyone knows a family that has been affected by autism. What is the role that faith plays in helping families cope? In this series of slice-of-life vignettes, God's grace glimmers through as Joel, an intellectually challenged young adult with autism, teaches those who love him that life requires a childlike faith, humility, trust, and forgiveness. A Place Called Acceptance: Ministry With Families of Children With Disabilities Kathleen Deyer Bolduc The book describes how to welcome and minister to families of children with disabilities. The author discusses theology and disability, the grief process some parents experience, and the impact of disabilities on family systems. Including People with Disabilities in Faith Communities: A Guide for Service Providers, Families & Congregations Eric Carter This book addresses how faith communities, service providers, and families can work together to support the full participation of individuals with disabilities in the faith community of their choice. -

Autism Terminology Guidelines

The language we use to talk about autism is important. A paper published in our journal (Kenny, Hattersley, Molins, Buckley, Povey & Pellicano, 2016) reported the results of a survey of UK stakeholders connected to autism, to enquire about preferences regarding the use of language. Based on the survey results, we have created guidelines on terms which are most acceptable to stakeholders in writing about autism. Whilst these guidelines are flexible, we would like researchers to be sensitive to the preferences expressed to us by the UK autism community. Preferred language The survey highlighted that there is no one preferred way to talk about autism, and researchers must be sensitive to the differing perspectives on this issue. Amongst autistic adults, the term ‘autistic person/people’ was the most commonly preferred term. The most preferred term amongst all stakeholders, on average, was ‘people on the autism spectrum’. Non-preferred language: 1. Suffers from OR is a victim of autism. Consider using the following terms instead: o is autistic o is on the autism spectrum o has autism / an autism spectrum disorder (ASD) / an autism spectrum condition (ASC) (Note: The term ASD is used by many people but some prefer the term 'autism spectrum condition' or 'on the autism spectrum' because it avoids the negative connotations of 'disability' or 'disorder'.) 2. Kanner’s autism 3. Referring to autism as a disease / illness. Consider using the following instead: o autism is a disability o autism is a condition 4. Retarded / mentally handicapped / backward. These terms are considered derogatory and offensive by members of the autism community and we would advise that they not be used. -

Real-Time 3D Graphic Augmentation of Therapeutic Music Sessions for People on the Autism Spectrum

Real-time 3D Graphic Augmentation of Therapeutic Music Sessions for People on the Autism Spectrum John Joseph McGowan Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Edinburgh Napier University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2018 Declaration I, John McGowan, declare that the work contained within this thesis has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. Furthermore, the thesis is the result of the student’s own independent work. Published material associated with the thesis is detailed within the section on Associate Publications. Signed: Date: 12th October 2019 J J McGowan Abstract i Abstract This thesis looks at the requirements analysis, design, development and evaluation of an application, CymaSense, as a means of improving the communicative behaviours of autistic participants through therapeutic music sessions, via the addition of a visual modality. Autism spectrum condition (ASC) is a lifelong neurodevelopmental disorder that can affect people in a number of ways, commonly through difficulties in communication. Interactive audio-visual feedback can be an effective way to enhance music therapy for people on the autism spectrum. A multi-sensory approach encourages musical engagement within clients, increasing levels of communication and social interaction beyond the sessions. Cymatics describes a resultant visualised geometry of vibration through a variety of mediums, typically through salt on a brass plate or via water. The research reported in this thesis focuses on how an interactive audio-visual application, based on Cymatics, might improve communication for people on the autism spectrum. A requirements analysis was conducted through interviews with four therapeutic music practitioners, aimed at identifying working practices with autistic clients.