Lighthouse Mission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mathematical Circus & 'Martin Gardner

MARTIN GARDNE MATHEMATICAL ;MATH EMATICAL ASSOCIATION J OF AMERICA MATHEMATICAL CIRCUS & 'MARTIN GARDNER THE MATHEMATICAL ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA Washington, DC 1992 MATHEMATICAL More Puzzles, Games, Paradoxes, and Other Mathematical Entertainments from Scientific American with a Preface by Donald Knuth, A Postscript, from the Author, and a new Bibliography by Mr. Gardner, Thoughts from Readers, and 105 Drawings and Published in the United States of America by The Mathematical Association of America Copyright O 1968,1969,1970,1971,1979,1981,1992by Martin Gardner. All riglhts reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. An MAA Spectrum book This book was updated and revised from the 1981 edition published by Vantage Books, New York. Most of this book originally appeared in slightly different form in Scientific American. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 92-060996 ISBN 0-88385-506-2 Manufactured in the United States of America For Donald E. Knuth, extraordinary mathematician, computer scientist, writer, musician, humorist, recreational math buff, and much more SPECTRUM SERIES Published by THE MATHEMATICAL ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA Committee on Publications ANDREW STERRETT, JR.,Chairman Spectrum Editorial Board ROGER HORN, Chairman SABRA ANDERSON BART BRADEN UNDERWOOD DUDLEY HUGH M. EDGAR JEANNE LADUKE LESTER H. LANGE MARY PARKER MPP.a (@ SPECTRUM Also by Martin Gardner from The Mathematical Association of America 1529 Eighteenth Street, N.W. Washington, D. C. 20036 (202) 387- 5200 Riddles of the Sphinx and Other Mathematical Puzzle Tales Mathematical Carnival Mathematical Magic Show Contents Preface xi .. Introduction Xlll 1. Optical Illusions 3 Answers on page 14 2. Matches 16 Answers on page 27 3. -

Techniques Classes

TECHNIQUES CLASSES These hands-on classes are ideal for both novice cooking students and those experienced students seeking to refresh, enhance, and update their abilities. The recipe packages feature both exciting, up-to-the minute ideas and tried-and-true classic dishes arranged in a sequence of lessons that allows for fast mastery of critical cooking skills. Students seeking increased kitchen confidence will acquire fundamental kitchen skills, execute important cooking techniques, learn about common and uncommon ingredients, and create complex multi-component specialty dishes. All courses are taught in our state-of-the-art ICASI facility by professional chefs with extensive restaurant experience. Prerequisites: Because of the continuity of skills, it is strongly recommended that Basic Techniques series will be taken in order. Attendance at the first class of a series is mandatory. Basic Techniques of Cooking 1 (4 Sessions) Hrvatin Monday, March 1, 8, 15, 22, 2021 6:00 pm ($345, 4x3hrs, 1.2 CEU) Week 1: Knife Skills: French Onion Soup, Ratatouille, Vegetarian Spring Rolls, Vegetable Tempura, Garden Vegetable Frittata Week 2: Stocks and Soups: Vegetable Stock, Fish Stock, Chicken Stock, Beef Stock, Black Bean Soup, Chicken Noodle Soup, Beef Consommé, Cream of Mushroom Soup, Puree of Asparagus Soup Week 3: Grains and Potatoes: Creamy Polenta, Spicy Braised Lentils, Risotto, Israeli Cous Cous, Pommes Frites, Potato Grain, Roasted Fingerling Potatoes, Baked Sweet Potatoes Week 4: Salads and Dressings: Bulgur Salad with White Wine Vinaigrette, -

Spring 2019 CE and March-May Calendar

ACC COMMUNITY EDUCATION–SPRING 2019 Advance registration required. Please register one week in advance. To register with debit or credit card call 989 358-7271. Visit our website to download the schedule at: www.alpenavolunteercenter.org – OR – through ACC’s website at www.alpenacc.edu – Select About, then select Visitors, [from left pane] select Volunteer Center, scroll toward bottom, under Community Education, click on “Please take a moment to browse through our classes.” COOKING CLASSES 19-01: CHINESE COOKING with JIMMY CHEN: Instructor Jimmy Chen owns Alpena’s popular and highly rated Hunan Chinese restaurant, which has served the area for decades with an extensive menu of Asian dishes. Jimmy calls upon his background, upbringing, culinary training and experience, and Asian culture to present a fascinating, fun, and flavorful class. Combining his expertise and engaging personality. Jimmy will guide participants in creating egg rolls and fried rice with the unique and rich flavors only obtained when prepared with proper high-quality traditional ingredients, seasonings, and techniques. Limit of 10 students. DATE Wednesday, March 13 TIME: 5:30-7:30 pm ROOM: CTR 104/102 FEE: $25 19-02: MEXICAN – TEX MEX CUISINE: Instructor Cathy Gutierrez-Abraham brings Tex-Mex Hispanic cooking, learned at her father’s knee, and traditional family cultural experiences, combined with flavorful recipes. This is your opportunity to learn hands-on and share a delicious ethnic meal, learning proper techniques from a Mexican cook who grew up with them! The evening’s menu includes preparation and dining in traditional Tostadas, Arroz y Frijoles (Spanish rice and Beans). -

Bebe Rexha Qlondon’S the O2 Arena on June 27

Established 1961 28 T Tuesday, April 10, 2018 L i f e s t y l e G o s s i p The Vaccines: Rolling Stones like teenagers at Hyde Park he Vaccines’ Freddie Cowan “There was plenty of handbags. says The Rolling Stones act- Being in a band by its very nature Ted like teenagers when they is a very intense and volatile thing. supported them at Hyde Park in “You’re working, living and creat- 2013. The ‘If You Wanna’ guitarist- ing with these other three, four or and-vocalist was amazed by how five people in a room with no natu- unorganised things were back- ral sunlight, for up to 15 hours a stage, with each band member - Sir day. “If you’re working on some- Mick Jagger, Ronnie Wood and thing you really care about then I Keith Richards - arriving late apart think you’re always gonna have from drummer Charlie Watts. differences of opinion.” However, Speaking to Gordon Smart on Justin is very happy with the final episode five of music show ‘Red result as they only chose songs Stripe presents: This Feeling TV’, that would suit the record to make Freddie said: “What I loved about it it a “focused” album. He continued: was that they seemed like a bunch “We wrote about 80 songs [when of teenagers. “Charlie Watts would working on the record] until we arrive first. “He was annoyed that whittled it down to the final cut. “I he was on time and everyone else think the mistake we’ve made in was late. -

RSD List 2020

Artist Title Label Format Format details/ Reason behind release 3 Pieces, The Iwishcan William Rogue Cat Resounds12" Full printed sleeve - black 12" vinyl remastered reissue of this rare cosmic, funked out go-go boogie bomb, full of rapping gold from Washington D.C's The 3 Pieces.Includes remixes from Dan Idjut / The Idjut Boys & LEXX Aashid Himons The Gods And I Music For Dreams /12" Fyraften Musik Aashid Himons classic 1984 Electonic/Reggae/Boogie-Funk track finally gets a well deserved re-issue.Taken from the very rare sought after album 'Kosmik Gypsy.The EP includes the original mix, a lovingly remastered Fyraften 2019 version.Also includes 'In a Figga of Speech' track from Kosmik Gypsy. Ace Of Base The Sign !K7 Records 7" picture disc """The Sign"" is a song by the Swedish band Ace of Base, which was released on 29 October 1993 in Europe. It was an international hit, reaching number two in the United Kingdom and spending six non-consecutive weeks at number one on the Billboard Hot 100 chart in the United States. More prominently, it became the top song on Billboard's 1994 Year End Chart. It appeared on the band's album Happy Nation (titled The Sign in North America). This exclusive Record Store Day version is pressed on 7"" picture disc." Acid Mothers Temple Nam Myo Ho Ren Ge Kyo (Title t.b.c.)Space Age RecordingsDouble LP Pink coloured heavyweight 180 gram audiophile double vinyl LP Not previously released on vinyl Al Green Green Is Blues Fat Possum 12" Al Green's first record for Hi Records, celebrating it's 50th anniversary.Tip-on Jacket, 180 gram vinyl, insert with liner notes.Split green & blue vinyl Acid Mothers Temple & the Melting Paraiso U.F.O.are a Japanese psychedelic rock band, the core of which formed in 1995.The band is led by guitarist Kawabata Makoto and early in their career featured many musicians, but by 2004 the line-up had coalesced with only a few core members and frequent guest vocalists. -

Towards a Holistic Interpretation of Musical Genre Analysis Thesis

1 JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES Chris Kemp Towards a Holistic Interpretation of Musical Genre Analysis JYVÄSKYLÄN YLIOPISTO 1 2 JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES Chris Kemp Towards a Holistic Interpretation of Musical Genre Analysis Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by permission of the Faculty of Humanities at the University of Jyväskylä, in Auditorium S212, on June 10, 2004 at 12 o’clock noon. 2 3 Towards a Holistic Interpretation of Musical Genre Analysis JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 3 4 Chris Kemp Towards a Holistic Interpretation of Musical Genre Analysis Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by permission of the Faculty of Humanities at the University of Jyväskylä, in Auditorium S212, on June 10, 2004 at 12 o’clock noon. 4 5 ABSTRACT Kemp, Chris Towards a holistic interpretation of musical genre analysis Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä, 2004 ? (Jyväskylä Studies in Humanities ISSN ISBN Diss In the past, exploration of music has focused on analysis by formalists, refferentialists and through social, semiotic and anthropological viewpoints including Schenkerian-Yeston (1977), Semiotic-Eco (1977), and Motivic-Ruwet (1987). Although each has its merits in the formal analysis of music, few explore genre identification. In musical genre studies the exploration of musical, paramusical (extramusical) and perceptual elements are essential to facilitate a full understanding of the subject area. Johnson in Zorn supports such a perspective in his argument for a holistic approach to musical analysis (Zorn 2000:29). The multidisciplinary nature of music and the discourses embodied in its creation, development and dissemination utilise a range of signifiers for identification advocating the utilisation of a “hybrid” (Wickens 1999) methodology combining quantitative and qualitative analysis. -

Ceramic Mold List 19JUL2021

AmbientAtelier.com Kindling For the Soul (HOT PINK) : Arranged alphabetically by brand, then partially numerical. MAY not be available for purchase; just ask if SOLD. BRAND NUMBER DESCR LOCATIONWEIGHTVALUE DC PHOTO 1stBay Alberta 469 fluted jar 4T Alberta 503 Bowl? 3M3 x Alberta 852 .. 2ndBot Alberta 856 Large Shepherd Boy? 2ndBay Alberta 927 .. A 3MEnd 3MEnd x Alberta 927 .. 3M2 x Alberta 927 .. 3M2 x Alberta 1209 2ndTOP Alberta 1213 3rdTop Alberta 1088A TR Alberta 1107T 2ndTop Alberta 778 Wings and tail 2ndTOP SOLD x/E Alberta 1088 2ndBay SOLD x/E Alberta 1804 17" Poinsettia Tree 4th SOLD SG Arnels 803 X2 & 3rd TOP 2ndBay X Arnels 204 square handle mug SOLD GT Arnels 731 A Pitcher 11 inch 2ndBay 59 SOLD x51/E Atlantic 78 2ndBot Atlantic 178 178? 5thMid Atlantic 210 2T Atlantic 290 Vegetables, corn, 5thMid Atlantic 516 Adorning angel body 5thTop Atlantic 724 Hobbit House Home Atlantic 827 2ndTop Atlantic 1399 2 small swans 3M2 x x/E Atlantic 1439 4thMid Atlantic 1450 sheild wall plaque bust base 3B x/E Atlantic 1630 1630: Victorian Angel wings and scarf 2 pieces 2ndBot 18 x/E Atlantic 1687 SW Vase TR Atlantic 1801 Rose candle holder 3T Atlantic 1866 behind 3rdMid x AmbientAtelier.com Kindling For the Soul (HOT PINK) : Arranged alphabetically by brand, then partially numerical. MAY not be available for purchase; just ask if SOLD. Atlantic 516A&B: 516 Adoring Angel WINGS AND HANDS (x2?) 3rdTOP/2ndMID37 45 x/E Atlantic 1791 Optional Candle Holder Holly 2ndBay SOLD SG Atlantic 1791 Optional Candle Holder Holly 2ndBay SOLD SG Atlantic 1874 Christmas Tree Holly/Poinsettia 1stBay SOLD x/E Atlantic 407 Santa's Face 1stBay 45 SOLD 4 SG Atlantic Large SABRINA Base SOLD Atlantic 1828 optional candle holder 3rd SOLD SG Atlantic 1794 Holly Tree 20" without base SOLD SG Bell 2033 shell? 1stBay Big Tex? 49 horse mug 3rdTop BJ Molds 166. -

Fragrance List 2019

VIRGINIA CANDLE SUPPLY - FRAGRANCE LIST 2019 Fragrance Description Abercrombie Fierce Type Similar to the A&F signature scent…rugged, masculine blend of fresh citrus and warm musk. After Midnight Dark and seductive with a blend of musk, floral, and fresh citrus. Almond Pastries A light, flaky pastry filled with sweet almond filling. Amish Harvest A warm spicy blend with slight buttery notes reminiscent of an autumn harvest celebration. Angel Wings Sweet musk notes embrace light floral nuances of jasmine, white flowers and lilacs. Apple Butter A pleasantly sweet combination of fresh apples, sugar, and spice. Apple Cinnamon Freshly picked apples blended with cinnamon. Apple Jack & Peel Apple and spices with a sweet background. Apple Maple Bourbon A fantastic fall fragrance of crisp apples, rich vanilla and maple infused with bourbon. Apple S'mores Sweet aroma of the fire roasted marshmallow treat with crisp apples and cinnamon. Aspen Winter Snow covered pine trees and juicy citrus mingle with heady vanilla and spicy cloves. Baby Powder It's a strong, clean, soft, powdery fragrance. Baked Pear & Cinnamon Delicious pears, enhanced with cinnamon and spices for a rich, warm fragrance. Banana Smells just like a freshly peeled banana. Banana Cream Pie The aroma of freshly made banana cream pie. Banana Nut Bread Fresh baked classic with cooked bananas and nuts. Banana Pudding Wonderful aroma of creamy banana pudding with vanilla wafers and a meringue topping Barber Shop Musk blended with a fresh & clean aroma that is sure to remind you of an old timey barber shop. Bayberry The perfect blend of fir and balsam with the just the right amount of nutmeg and spice. -

![MTV Meet Bebe Rexha: the Anti-Katy Perry of Pop. [T]He New York Native](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6186/mtv-meet-bebe-rexha-the-anti-katy-perry-of-pop-t-he-new-york-native-3766186.webp)

MTV Meet Bebe Rexha: the Anti-Katy Perry of Pop. [T]He New York Native

MTV Meet Bebe Rexha: The Anti-Katy Perry of Pop. [T]he New York native takes a more “f–ked up” approach, drawing inspiration from Angelina Jolie’s “Girl, Interrupted” and Kirsten Dunst’s “Melancholia.” Billboard Buzzing, Breaking, Blowing Up: Meet the acts who will help define 2014. Singer/songwriter channels inner demons into hits ELLE Her blisteringly honest songs are as wounded as Tove Lo, incisive as Sia, and Pink-with-a-blowtorch angry… V Magazine THE GIRL WITH THE PLATINUM TOUCH DEFINES WHAT SHE WILL BE USA Today Meet the Vocal Wizards Behind EDM’s Biggest Hits VIBE One listen to her strong pipes and edgy lyrics on “I Can’t Stop Drinking About You,” you’ll want to give her a shot. FUSE TV Bebe Rexha's come a long way since her days fronting Pete Wentz's side project, the Black Cards, and 2015 is looking to be the most eventful yet Perez Hilton We LOVE us some Bebe Rexha! And, as the months have gone by and she's come more into herself as an artist we have started to see her and less as some alter-pop outsider and more like whom she really is - Katy Perry's younger and edgier sister! Both write BIG pop songs! And, like Katy, Bebe, not only writes her own songs but she also writes hits for other people too! Rexha is giving us pop with some serious bite - and we LOVE it!! Just Jared sexy and seductive Idolator Bebe Rexha‘s no stranger to a mean pop hook… a dark, devastating (and autobiographical!) heartbreak anthem. -

Summersommer18

ISSN 1847-7674 summersommer18 www.istra.com Savudrija Jelovice Salvore Plovanija Požane Kaštel Umag Umago Buje Buie Grožnjan Buzet Grisignana Brtonigla Oprtalj Roč Verteneglio Rijeka Portole Opatija A N I R M Lupoglav Kaštelir Labinci Novigrad Hum Castellier Motovun Cittanova Santa Domenica Vižinada BUTONIGA Visinada Montona Tar-Vabriga Torre-Abrega Cerovlje Višnjan Visignano Poreč Pazin Gračišće Parenzo Tinjan Pićan Sv. Lovreč Kršan Funtana Fontane Sv. Petar u Šumi Brestova Žminj Vrsar Kanfanar Above Oben: Orsera Plomin A [no. 44] Limski kanal enjoyistra summersommer Brijuni Islands / Brioni-Inseln Š A R ISSN 1847-7674 impressumimpressum Cover Page Titelseite: Svetvinčenat [01.07. - 30.09.2018] Brtonigla-Verteneglio Rovinj Barban Rabac Publisher | Herausgeber Labin Rovigno Bale Istria Tourist Board Here one can still hear the har- Valle Raša Tourismusverband Istrien contentinhalt monious sounds of different Pionirska 1, HR-52440 PoreË-Parenzo languages and the songs of +385 (0)52 452797, [email protected] enjoymysteries 04-11 crickets and nightingales. Here For the publisher one can imbibe the traditional Für den Herausgeber enjoyheritage 12-19 values of the villages and fisher- Denis Ivošević men. Here one can rest the soul Editor | Redakteur enjoygourmet 20-23 in the shadow of centuries-old Vodnjan oak trees and authentic rural Vesna IvanoviÊ enjoyfamily 24-29 Dignano Design | Gestaltung homesteads surrounded by qui- Marčana Fabrika, Pula et fields watched over by small enjoyevents 30-47 Fažana Photo credits | Fotos churches with bell gables ... Fasana Hier ist es immer noch mög- Danijel Bartolić/Nunu Production enjoyattractions 48-49 lich den harmonischen Klang NP Brijuni Martin Čotar, Igor Zirojević National park Julien Duval/Envy, Studio Sonda enjoygames 50-51 verschiedener Sprachen zu Pula Markus Haslinger/ArtRedaktionsteam hören, genauso wie das Zir- Pola & Istria TB Archive | TVI Archiv enjoymuseums 52-53 pen der Grillen und den Gesang Print | Druck der Nachtigallen, und auch die Ližnjan Radin print d.o.o. -

Sorority Noise – As Cities Burn – Moon Taxi – Cady Groves & More

issue 43 SORORITY NOISE – AS CITIES BURN – MOON TAXI – CADY GROVES & MORE HIGHLIGHT MAGAZINE HIGHLIGHTMAGAZINE.NET - 1 september 05 this or that 08 clothing highlight 11 label highlight 12 venue highlight 14 industry highlight 16 highlighted artists 17 film highlight 18 sorority noise 22 moon taxi 26 as cities burn 30 cady groves 34 bebe rexha 48 tour round up pierce the veil halsey one direction neck deep one direction lord huron 56 reviews 4 - HIGHLIGHTMAGAZINE.NET BEBE REXHA 34 SORORITY NOISE 18 CADY GROVES 30 6 - HIGHLIGHTMAGAZINE.NET INDUSTRY HIGHLIGHT 14 34 - HIGHLIGHTMAGAZINE.NET HIGHLIGHTMAGAZINE.NET - 35 36 - HIGHLIGHTMAGAZINE.NET HOME: Brooklyn, New York NOW JAMMING: “I Can’t Stop Drinking About You” CURRENTLY: Preparing for a tour with Nick Jonas ONE OF THE SUMMER’S BIGGEST HITS WAS David Guetta’s “Hey Mama,” an electro, house anthem that features pop icon Nicki Minaj and EDM artist Afrojack. However, one of the biggest questions following the release of the song was who sings the catchy chorus. The answer? Brooklyn native Bebe Rexha. At only 25 years old, the singer-songwriter has penned massive hits such as “The Monster,” the hit single notably sung by Eminem and Rihanna, as well as co-writing “Hey Mama” alongside Guetta. She was featured on the 2013 summer hit “Take Me Home” by Cash Cash and was also the lead singer for Black Cards, Pete Wentz’s short-lived, post-hiatus side project, from 2010 to 2012. Gaining her impressive laundry list of credits as well as recognition for them has been a bit of a rollercoaster. -

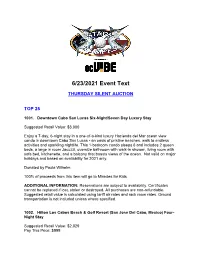

6/23/2021 Event Text

6/23/2021 Event Text THURSDAY SILENT AUCTION TOP 25 1001. Downtown Cabo San Lucas Six-Night/Seven Day Luxury Stay Suggested Retail Value: $3,000 Enjoy a 7-day, 6-night stay in a one-of-a-kind luxury Hacienda del Mar ocean view condo in downtown Cabo San Lucas - an oasis of pristine beaches, walk to endless activities and sparkling nightlife. This 1-bedroom condo sleeps 6 and includes 2 queen beds, a large in room Jacuzzi, oversize bathroom with walk-in shower, living room with sofa bed, kitchenette, and a balcony that boasts views of the ocean. Not valid on major holidays and based on availability for 2021 only. Donated by Paula Wilhelm. 100% of proceeds from this item will go to Miracles for Kids. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION: Reservations are subject to availability. Certificates cannot be replaced if lost, stolen or destroyed. All purchases are non-refundable. Suggested retail value is calculated using tariff air rates and rack room rates. Ground transportation is not included unless where specified. 1002. Hilton Los Cabos Beach & Golf Resort (San Jose Del Cabo, Mexico) Four- Night Stay Suggested Retail Value: $2,029 Pay This Price: $999 Enjoy a four-night stay in a deluxe ocean view room, EP basis. Valid through TBD, based on availability. Excludes major holidays (December 10 - January 4) and blackout dates apply. Discover a new definition of luxury and service at the finest of Cabo San Lucas hotels, the Hilton Los Cabos Beach & Golf Resort. Treat your Mexico travel with the opulent majesty of a true Four Diamond hotel.