Anuran Community of a Cocoa Agroecosystem in Southeastern Brazil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Herpetofauna of Serra Do Timbó, an Atlantic Forest Remnant in Bahia State, Northeastern Brazil

Herpetology Notes, volume 12: 245-260 (2019) (published online on 03 February 2019) Herpetofauna of Serra do Timbó, an Atlantic Forest remnant in Bahia State, northeastern Brazil Marco Antonio de Freitas1, Thais Figueiredo Santos Silva2, Patrícia Mendes Fonseca3, Breno Hamdan4,5, Thiago Filadelfo6, and Arthur Diesel Abegg7,8,* Originally, the Atlantic Forest Phytogeographical The implications of such scarce knowledge on the Domain (AF) covered an estimated total area of conservation of AF biodiversity are unknown, but they 1,480,000 km2, comprising 17% of Brazil’s land area. are of great concern (Lima et al., 2015). However, only 160,000 km2 of AF still remains, the Historical data on deforestation show that 11% of equivalent to 12.5% of the original forest (SOS Mata AF was destroyed in only ten years, leading to a tragic Atlântica and INPE, 2014). Given the high degree of estimate that, if this rhythm is maintained, in fifty years threat towards this biome, concomitantly with its high deforestation will completely eliminate what is left of species richness and significant endemism, AF has AF outside parks and other categories of conservation been classified as one of twenty-five global biodiversity units (SOS Mata Atlântica, 2017). The future of the AF hotspots (e.g., Myers et al., 2000; Mittermeier et al., will depend on well-planned, large-scale conservation 2004). Our current knowledge of the AF’s ecological strategies that must be founded on quality information structure is based on only 0.01% of remaining forest. about its remnants to support informed decision- making processes (Kim and Byrne, 2006), including the investigations of faunal and floral richness and composition, creation of new protected areas, the planning of restoration projects and the management of natural resources. -

Comportamendo Animal.Indd

Valeska Regina Reque Ruiz (Organizadora) Comportamento Animal Atena Editora 2019 2019 by Atena Editora Copyright da Atena Editora Editora Chefe: Profª Drª Antonella Carvalho de Oliveira Diagramação e Edição de Arte: Geraldo Alves e Lorena Prestes Revisão: Os autores Conselho Editorial Prof. Dr. Alan Mario Zuffo – Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul Prof. Dr. Álvaro Augusto de Borba Barreto – Universidade Federal de Pelotas Prof. Dr. Antonio Carlos Frasson – Universidade Tecnológica Federal do Paraná Prof. Dr. Antonio Isidro-Filho – Universidade de Brasília Profª Drª Cristina Gaio – Universidade de Lisboa Prof. Dr. Constantino Ribeiro de Oliveira Junior – Universidade Estadual de Ponta Grossa Profª Drª Daiane Garabeli Trojan – Universidade Norte do Paraná Prof. Dr. Darllan Collins da Cunha e Silva – Universidade Estadual Paulista Profª Drª Deusilene Souza Vieira Dall’Acqua – Universidade Federal de Rondônia Prof. Dr. Eloi Rufato Junior – Universidade Tecnológica Federal do Paraná Prof. Dr. Fábio Steiner – Universidade Estadual de Mato Grosso do Sul Prof. Dr. Gianfábio Pimentel Franco – Universidade Federal de Santa Maria Prof. Dr. Gilmei Fleck – Universidade Estadual do Oeste do Paraná Profª Drª Girlene Santos de Souza – Universidade Federal do Recôncavo da Bahia Profª Drª Ivone Goulart Lopes – Istituto Internazionele delle Figlie de Maria Ausiliatrice Profª Drª Juliane Sant’Ana Bento – Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul Prof. Dr. Julio Candido de Meirelles Junior – Universidade Federal Fluminense Prof. Dr. Jorge González Aguilera – Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul Profª Drª Lina Maria Gonçalves – Universidade Federal do Tocantins Profª Drª Natiéli Piovesan – Instituto Federal do Rio Grande do Norte Profª Drª Paola Andressa Scortegagna – Universidade Estadual de Ponta Grossa Profª Drª Raissa Rachel Salustriano da Silva Matos – Universidade Federal do Maranhão Prof. -

Novos Registros De Dendropsophus Anceps (Anura, Hylidae), Para Os Estados Do Rio De Janeiro E Bahia

Biotemas, 23 (1): 229-234, março de 2010 Comunicação Breve229 ISSN 0103 – 1643 Novos registros de Dendropsophus anceps (Anura, Hylidae), para os estados do Rio de Janeiro e Bahia Rodrigo de Oliveira Lula Salles* Marcelo Gomes Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Museu Nacional, Departamento de Vertebrados Quinta da Boa Vista, São Cristóvão, CEP 20940-040. Rio de Janeiro – RJ, Brasil *Autor para correspondência [email protected] Submetido em 14/09/2009 Aceito para publicação em 02/12/2009 Resumo Este estudo apresenta novos registros de Dendropsophus anceps para os estados do Rio de Janeiro e Bahia, através da análise de espécimes depositados na coleção de anfíbios do Museu Nacional/Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro. Para o estado do Rio de Janeiro a espécie foi registrada em mais oito localidades e para Bahia duas, ampliando a distribuição em 100km ao nordeste do Brasil. Unitermos: Bahia, Dendropsophus anceps, distribuição geográfica, Rio de Janeiro Abstract New records of Dendropsophus anceps (Anura, Hylidae) for the states of Rio de Janeiro and Bahia. This study reports the new records of Dendropsophus anceps for the states of Rio de Janeiro and Bahia, through the analysis of specimens deposited in the amphibian collection of the Museu Nacional/Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro. In the state of Rio de Janeiro, the species was confirmed in eight more localities and for the state of Bahia two more localities, expanding the distribution range by 100km to northeastern Brazil. Key words: Bahia, Dendropsophus anceps, geographic distribution, Rio de Janeiro Revista Biotemas, 23 (1), março de 2010 2000) e para os municípios de Teixeira de Freitas, Porto Seguro, Itapebi, Una e Jussari 230 R. -

For Review Only

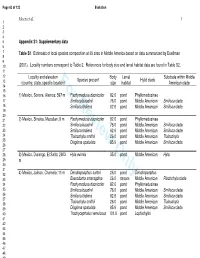

Page 63 of 123 Evolution Moen et al. 1 1 2 3 4 5 Appendix S1: Supplementary data 6 7 Table S1 . Estimates of local species composition at 39 sites in Middle America based on data summarized by Duellman 8 9 10 (2001). Locality numbers correspond to Table 2. References for body size and larval habitat data are found in Table S2. 11 12 Locality and elevation Body Larval Subclade within Middle Species present Hylid clade 13 (country, state, specific location)For Reviewsize Only habitat American clade 14 15 16 1) Mexico, Sonora, Alamos; 597 m Pachymedusa dacnicolor 82.6 pond Phyllomedusinae 17 Smilisca baudinii 76.0 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 18 Smilisca fodiens 62.6 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 19 20 21 2) Mexico, Sinaloa, Mazatlan; 9 m Pachymedusa dacnicolor 82.6 pond Phyllomedusinae 22 Smilisca baudinii 76.0 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 23 Smilisca fodiens 62.6 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 24 Tlalocohyla smithii 26.0 pond Middle American Tlalocohyla 25 Diaglena spatulata 85.9 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 26 27 28 3) Mexico, Durango, El Salto; 2603 Hyla eximia 35.0 pond Middle American Hyla 29 m 30 31 32 4) Mexico, Jalisco, Chamela; 11 m Dendropsophus sartori 26.0 pond Dendropsophus 33 Exerodonta smaragdina 26.0 stream Middle American Plectrohyla clade 34 Pachymedusa dacnicolor 82.6 pond Phyllomedusinae 35 Smilisca baudinii 76.0 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 36 Smilisca fodiens 62.6 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 37 38 Tlalocohyla smithii 26.0 pond Middle American Tlalocohyla 39 Diaglena spatulata 85.9 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 40 Trachycephalus venulosus 101.0 pond Lophiohylini 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Evolution Page 64 of 123 Moen et al. -

HÁBITO ALIMENTAR DA RÃ INVASORA Lithobates Catesbeianus (SHAW, 1802) E SUA RELAÇÃO COM ANUROS NATIVOS NA ZONA DA MATA DE MINAS GERAIS, BRASIL

EMANUEL TEIXEIRA DA SILVA HÁBITO ALIMENTAR DA RÃ INVASORA Lithobates catesbeianus (SHAW, 1802) E SUA RELAÇÃO COM ANUROS NATIVOS NA ZONA DA MATA DE MINAS GERAIS, BRASIL Dissertação apresentada à Universidade Federal de Viçosa, como parte das exigências do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biologia Animal, para obtenção do título de Magister Scientiae. VIÇOSA MINAS GERAIS - BRASIL 2010 EMANUEL TEIXEIRA DA SILVA HÁBITO ALIMENTAR DA RÃ INVASORA Lithobates catesbeianus (SHAW, 1802) E SUA RELAÇÃO COM ANUROS NATIVOS NA ZONA DA MATA DE MINAS GERAIS, BRASIL Dissertação apresentada à Universidade Federal de Viçosa, como parte das exigências do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biologia Animal, para obtenção do título de Magister Scientiae. APROVADA: 09 de abril de 2010 __________________________________ __________________________________ Prof. Renato Neves Feio Prof. José Henrique Schoereder (Coorientador) (Coorientador) __________________________________ __________________________________ Prof. Jorge Abdala Dergam dos Santos Prof. Paulo Christiano de Anchietta Garcia _________________________________ Prof. Oswaldo Pinto Ribeiro Filho (Orientador) Aos meus pais, pelo estímulo incessante que sempre me forneceram desde que rabisquei aqueles livros da série “O mundo em que vivemos”. ii AGRADECIMENTOS Quantas pessoas contribuíram para a realização deste trabalho! Dessa forma, é tarefa difícil listar todos os nomes... Mas mesmo se eu me esquecer de alguém nesta seção, a ajuda prestada não será esquecida jamais. Devo deixar claro que os agradecimentos presentes na minha monografia de graduação são também aqui aplicáveis, uma vez que aquele trabalho está aqui continuado. Por isso, vou me ater principalmente àqueles cuja colaboração foi indispensável durante estes últimos dois anos. Agradeço à Universidade Federal de Viçosa, pela estrutura física e humana indispensável à realização deste trabalho, além de tudo o que me ensinou nestes anos. -

From a Cocoa Plantation in Southern Bahia, Brazil

NORTH-WESTERN JOURNAL OF ZOOLOGY 12 (1): 159-165 ©NwjZ, Oradea, Romania, 2016 Article No.: e151512 http://biozoojournals.ro/nwjz/index.html Diet of Dendropsophus branneri (Cochran, 1948) (Anura: Hylidae) from a cocoa plantation in southern Bahia, Brazil Indira Maria CASTRO1, Raoni REBOUÇAS1,2 and Mirco SOLÉ1,3,* 1. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Zoologia, Universidade Estadual de Santa Cruz, Rodovia Jorge Amado, Km. 16, Salobrinho, CEP: 45662-900 Ilhéus, Bahia, Brazil. 2. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências Biológicas (Biologia Animal), Universidade Federal do Espirito Santo, Av. Fernando Ferrari, 514, Prédio Bárbara Weinberg, 29075-910 Vitória, Espirito Santo, Brazil. 3. Departamento de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Estadual de Santa Cruz, Rodovia Jorge Amado, km. 16, Salobrinho, CEP: 45662-900 Ilhéus, Bahia, Brasil. *Corresponding author, M. Solé, E-mail: [email protected] Received: 11. June 2015 / Accepted: 18. September 2015 / Available online: 30. May 2016 / Printed: June 2016 Abstract. In this study we analyze the diet of a population of Dendropsophus branneri from a cocoa plantation in southern Bahia, Brazil. Frogs were captured monthly from August 2010 to July 2011. Stomach contents were retrieved through stomach-flushing and later identified to order level. Our results show that D. branneri feeds mainly on arthropds, such as Diptera, larval Lepidoptera and Araneae. Based on the identified food items and the low number of prey per stomach we conclude that the studied population of D. branneri uses a “sit and wait” strategy. We further conclude that stomach flushing can be successfully applied to frogs from a size of 14.4mm. Key words: trophic resources, stomach flushing, feeding habits, Hylidae, cabruca, Atlantic Rainforest. -

Amphibians from the Centro Marista São José Das Paineiras, in Mendes, and Surrounding Municipalities, State of Rio De Janeiro, Brazil

Herpetology Notes, volume 7: 489-499 (2014) (published online on 25 August 2014) Amphibians from the Centro Marista São José das Paineiras, in Mendes, and surrounding municipalities, State of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Manuella Folly¹ *, Juliana Kirchmeyer¹, Marcia dos Reis Gomes¹, Fabio Hepp², Joice Ruggeri¹, Cyro de Luna- Dias¹, Andressa M. Bezerra¹, Lucas C. Amaral¹ and Sergio P. de Carvalho-e-Silva¹ Abstract. The amphibian fauna of Brazil is one of the richest in the world, however, there is a lack of information on its diversity and distribution. More studies are necessary to increase our understanding of amphibian ecology, microhabitat choice and use, and distribution of species along an area, thereby facilitating actions for its management and conservation. Herein, we present a list of the amphibians found in one remnant area of Atlantic Forest, at Centro Marista São José das Paineiras and surroundings. Fifty-one amphibian species belonging to twenty-five genera and eleven families were recorded: Anura - Aromobatidae (one species), Brachycephalidae (six species), Bufonidae (three species), Craugastoridae (one species), Cycloramphidae (three species), Hylidae (twenty-four species), Hylodidae (two species), Leptodactylidae (six species), Microhylidae (two species), Odontophrynidae (two species); and Gymnophiona - Siphonopidae (one species). Visits to herpetological collections were responsible for 16 species of the previous list. The most abundant species recorded in the field were Crossodactylus gaudichaudii, Hypsiboas faber, and Ischnocnema parva, whereas the species Chiasmocleis lacrimae was recorded only once. Keywords: Anura, Atlantic Forest, Biodiversity, Gymnophiona, Inventory, Check List. Introduction characteristics. The largest fragment of Atlantic Forest is located in the Serra do Mar mountain range, extending The Atlantic Forest extends along a great part of from the coast of São Paulo to the coast of Rio de Janeiro the Brazilian coast (Bergallo et al., 2000), formerly (Ribeiro et al., 2009). -

Amphibians of Santa Teresa, Brazil: the Hotspot Further Evaluated

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 857: 139–162 (2019)Amphibians of Santa Teresa, Brazil: the hotspot further evaluated 139 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.857.30302 RESEARCH ARTICLE http://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Amphibians of Santa Teresa, Brazil: the hotspot further evaluated Rodrigo Barbosa Ferreira1,2, Alexander Tamanini Mônico1,3, Emanuel Teixeira da Silva4,5, Fernanda Cristina Ferreira Lirio1, Cássio Zocca1,3, Marcio Marques Mageski1, João Filipe Riva Tonini6,7, Karen H. Beard2, Charles Duca1, Thiago Silva-Soares3 1Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia de Ecossistemas, Universidade Vila Velha, Campus Boa Vista, 29102-920, Vila Velha, ES, Brazil 2 Department of Wildland Resources and the Ecology Center, Utah State University, Logan, UT, USA 3Instituto Nacional da Mata Atlântica/Museu de Biologia Prof. Mello Leitão, 29650-000, Santa Teresa, ES, Brazil 4 Laboratório de Herpetologia, Departamento de Zoologia, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Avenida Antônio Carlos, 6627, Pampulha, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil 5 Centro de Estudos em Biologia, Centro Universitário de Caratinga, Avenida Niterói, s/n, Bairro Nossa Senhora das Graças, 35300-000, Caratinga, MG, Brazil 6 Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, 26 Oxford St, Cambridge, MA, USA 7 Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, 26 Oxford St, Cambridge, MA, USA Corresponding author: Rodrigo Barbosa Ferreira ([email protected]) Academic editor: A. Crottini | Received 4 October 2018 | Accepted 20 April 2019 | Published 25 June 2019 http://zoobank.org/1923497F-457B-43BA-A852-5B58BEB42CC1 Citation: Ferreira RB, Mônico AT, da Silva ET, Lirio FCF, Zocca C, Mageski MM, Tonini JFR, Beard KH, Duca C, Silva-Soares T (2019) Amphibians of Santa Teresa, Brazil: the hotspot further evaluated. -

Amphibians of Serra Bonita, Southern Bahia: a New Hotpoint

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 449: 105–130 (2014)Amphibians of Serra Bonita, southern Bahia: a new hotpoint... 105 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.449.7494 CHECKLIST http://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Amphibians of Serra Bonita, southern Bahia: a new hotpoint within Brazil’s Atlantic Forest hotspot Iuri Ribeiro Dias1,2, Tadeu Teixeira Medeiros3, Marcos Ferreira Vila Nova1, Mirco Solé1,2 1 Departamento de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Estadual de Santa Cruz, Rodovia Jorge Amado, km, 16, 45662-900 Ilhéus, Bahia, Brasil 2 Graduate Program in Applied Zoology, Universidade Estadual de Santa Cruz, Rodovia Jorge Amado, km 16, 45662-900 Ilhéus, Bahia, Brasil 3 Conselho de Curadores das Coleções Científicas, Universidade Estadual de Santa Cruz, Rodovia Jorge Amado, km 16, 45662-900 Ilhéus, Bahia, Brasil Corresponding author: Iuri Ribeiro Dias ([email protected]) Academic editor: F. Andreone | Received 12 March 2014 | Accepted 12 September 2014 | Published 22 October 2014 http://zoobank.org/4BE3466B-3666-4012-966D-350CA6551E15 Citation: Dias IR, Medeiros TT, Nova MFV, Solé M (2014) Amphibians of Serra Bonita, southern Bahia: a new hotpoint within Brazil’s Atlantic Forest hotspot. ZooKeys 449: 105–130. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.449.7494 Abstract We studied the amphibian community of the Private Reserve of Natural Heritage (RPPN) Serra Bonita, an area of 20 km2 with steep altitudinal gradients (200–950 m a.s.l.) located in the municipalities of Camacan and Pau-Brasil, southern Bahia State, Brazil. Data were obtained at 38 sampling sites (including ponds and transects within the forest and in streams), through active and visual and acoustic searches, pitfall traps, and opportunistic encounters. -

Instituto De Biociências – Rio Claro Programa De Pós

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL PAULISTA “JÚLIO DE MESQUITA FILHO” unesp INSTITUTO DE BIOCIÊNCIAS – RIO CLARO PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM CIÊNCIAS BIOLÓGICAS (ZOOLOGIA) ANFÍBIOS DA SERRA DO MAR: DIVERSIDADE E BIOGEOGRAFIA LEO RAMOS MALAGOLI Tese apresentada ao Instituto de Biociências do Câmpus de Rio Claro, Universidade Estadual Paulista, como parte dos requisitos para obtenção do título de doutor em Ciências Biológicas (Zoologia). Agosto - 2018 Leo Ramos Malagoli ANFÍBIOS DA SERRA DO MAR: DIVERSIDADE E BIOGEOGRAFIA Tese apresentada ao Instituto de Biociências do Câmpus de Rio Claro, Universidade Estadual Paulista, como parte dos requisitos para obtenção do título de doutor em Ciências Biológicas (Zoologia). Orientador: Prof. Dr. Célio Fernando Baptista Haddad Co-orientador: Prof. Dr. Ricardo Jannini Sawaya Rio Claro 2018 574.9 Malagoli, Leo Ramos M236a Anfíbios da Serra do Mar : diversidade e biogeografia / Leo Ramos Malagoli. - Rio Claro, 2018 207 f. : il., figs., gráfs., tabs., fots., mapas Tese (doutorado) - Universidade Estadual Paulista, Instituto de Biociências de Rio Claro Orientador: Célio Fernando Baptista Haddad Coorientador: Ricardo Jannini Sawaya 1. Biogeografia. 2. Anuros. 3. Conservação. 4. Diversidade funcional. 5. Elementos bióticos. 6. Mata Atlântica. 7. Regionalização. I. Título. Ficha Catalográfica elaborada pela STATI - Biblioteca da UNESP Campus de Rio Claro/SP - Ana Paula Santulo C. de Medeiros / CRB 8/7336 “To do science is to search for repeated patterns, not simply to accumulate facts, and to do the science of geographical ecology is to search for patterns of plant and animal life that can be put on a map. The person best equipped to do this is the naturalist.” Geographical Ecology. Patterns in the Distribution of Species Robert H. -

Seasonal and Habitat Structure of an Anuran Assemblage in A

An Acad Bras Cienc (2020) 92(1): e20190458 DOI 10.1590/0001-3765202020190458 Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências | Annals of the Brazilian Academy of Sciences Printed ISSN 0001-3765 I Online ISSN 1678-2690 www.scielo.br/aabc | www.fb.com/aabcjournal BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES Seasonal and habitat structure of an Running title: SEASONAL AND anuran assemblage in a semideciduous HABITAT STRUCTURE OF AN ANURAN ASSEMBLAGE forest area in Southeast Brazil Academy Section: BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES ELVIS A. PEREIRA, MATHEUS O. NEVES, JOSÉ LUIZ M.M. SUGAI, RENATO N. FEIO & DIEGO J. SANTANA e20190458 Abstract: In this study, we evaluated the reproductive activity and the temporal and spatial distributions of anuran assemblages in three environments within a semideciduous forest in Southeast Brazil, located at Municipality of Barão de Monte Alto, 92 State of Minas Gerais, Brazil. The fi eld activities were carried out during three consecutive (1) days, monthly throughout the rainy seasons of 2013–2014 and 2014–2015. We recorded 92(1) 28 anurans species, distributed in eight families. We observed the spatial-temporal distribution of some species, and their associated reproductive behaviors through exploration of vocalizations at different sites. The spatial and temporal distribution of the species seems to adapt to abiotic and biotic factors of their environment. Key words: Anuran community, community ecology, environmental heterogeneity, niche breadth, vocalization sites. INTRODUCTION community is defi ned as a group of organisms that coexist in a determined habitat and also Information about anuran habitat use and interact with one another and the surrounding reproductive ecology allows us to interpret environment (Begon et al. -

Composição, Distribuição Espacial E Sazonal Da Anurofauna De Córrego E Lagoa Em Uma Região Montana No Sudeste Do Brasil

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE OURO PRETO INSTITUTO DE CIÊNCIAS EXATAS E BIOLÓGICAS DEPARTAMENTO DE BIODIVERSIDADE, EVOLUÇÃO E MEIO AMBIENTE PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM ECOLOGIA DE BIOMAS TROPICAIS Dissertação de Mestrado Composição, distribuição espacial e sazonal da anurofauna de córrego e lagoa em uma região montana no sudeste do Brasil Ana Clara Franco de Magalhães Ouro Preto, agosto de 2015 Composição, distribuição espacial e sazonal da anurofauna de córrego e lagoa em uma região montana no sudeste do Brasil Autor: Ana Clara Franco de Magalhães Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Maria Rita Silvério Pires Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia de Biomas Tropicais, do Instituto de Ciências Exatas e Biológicas da Universidade Federal de Ouro Preto, como parte dos requisitos para obtenção do título de Mestre em Ecologia. Ouro Preto, agosto de 2015 M188c Magalhães, Ana Clara Franco de. Composição, distribuição espacial e sazonal da anurofauna de córrego e lagoa em uma região montana no sudeste do Brasil [manuscrito] / Ana Clara Franco de Magalhães. - 2015. 67f.: il.: color; grafs; tabs; mapas. Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Maria Rita Silvério Pires. Dissertação (Mestrado) - Universidade Federal de Ouro Preto. Instituto de Ciências Exatas e Biológicas. Departamento de Biodiversidade, Evolução e Meio Ambiente. Ecologia de Biomas Tropicais. 1. Comunidade Partilha de recursos (Ecologia) . 2. Habitat. 3. Anfibio . 4. Nicho (Ecologia). I. Pires, Maria Rita Silvério. II. Universidade Federal de Ouro Preto. III. Titulo. CDU: 597.6 Catalogação: www.sisbin.ufop.br "A natureza deve ser considerada como um todo, mas deve ser estudada em detalhe." (Mário Bunge) AGRADECIMENTOS Felizmente contei com o apoio de muitas pessoas durante as várias etapas conquistadas nestes dois anos de mestrado.