Giant Hogweed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNIVERSITY of READING Delivering Biodiversity and Pollination Services on Farmland

UNIVERSITY OF READING Delivering biodiversity and pollination services on farmland: a comparison of three wildlife- friendly farming schemes Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Agri-Environmental Research School of Agriculture, Policy and Development Chloe J. Hardman June 2016 Declaration I confirm that this is my own work and the use of all material from other sources has been properly and fully acknowledged. Chloe Hardman i Abstract Gains in food production through agricultural intensification have come at an environmental cost, including reductions in habitat diversity, species diversity and some ecosystem services. Wildlife- friendly farming schemes aim to mitigate the negative impacts of agricultural intensification. In this study, we compared the effectiveness of three schemes using four matched triplets of farms in southern England. The schemes were: i) a baseline of Entry Level Stewardship (ELS: a flexible widespread government scheme, ii) organic agriculture and iii) Conservation Grade (CG: a prescriptive, non-organic, biodiversity-focused scheme). We examined how effective the schemes were in supporting habitat diversity, species diversity, floral resources, pollinators and pollination services. Farms in CG and organic schemes supported higher habitat diversity than farms only in ELS. Plant and butterfly species richness were significantly higher on organic farms and butterfly species richness was marginally higher on CG farms compared to farms in ELS. The species richness of plants, butterflies, solitary bees and birds in winter was significantly correlated with local habitat diversity. Organic farms supported more evenly distributed floral resources and higher nectar densities compared to farms in CG or ELS. Compared to maximum estimates of pollen demand from six bee species, only organic farms supplied sufficient pollen in late summer. -

Impatiens Glandulifera (Himalayan Balsam) Chloroplast Genome Sequence As a Promising Target for Populations Studies

Impatiens glandulifera (Himalayan balsam) chloroplast genome sequence as a promising target for populations studies Giovanni Cafa1, Riccardo Baroncelli2, Carol A. Ellison1 and Daisuke Kurose1 1 CABI Europe, Egham, Surrey, UK 2 University of Salamanca, Instituto Hispano-Luso de Investigaciones Agrarias (CIALE), Villamayor (Salamanca), Spain ABSTRACT Background: Himalayan balsam Impatiens glandulifera Royle (Balsaminaceae) is a highly invasive annual species native of the Himalayas. Biocontrol of the plant using the rust fungus Puccinia komarovii var. glanduliferae is currently being implemented, but issues have arisen with matching UK weed genotypes with compatible strains of the pathogen. To support successful biocontrol, a better understanding of the host weed population, including potential sources of introductions, of Himalayan balsam is required. Methods: In this molecular study, two new complete chloroplast (cp) genomes of I. glandulifera were obtained with low coverage whole genome sequencing (genome skimming). A 125-year-old herbarium specimen (HB92) collected from the native range was sequenced and assembled and compared with a 2-year-old specimen from UK field plants (HB10). Results: The complete cp genomes were double-stranded molecules of 152,260 bp (HB92) and 152,203 bp (HB10) in length and showed 97 variable sites: 27 intragenic and 70 intergenic. The two genomes were aligned and mapped with two closely related genomes used as references. Genome skimming generates complete organellar genomes with limited technical and financial efforts and produces large datasets compared to multi-locus sequence typing. This study demonstrates the 26 July 2019 Submitted suitability of genome skimming for generating complete cp genomes of historic Accepted 12 February 2020 Published 24 March 2020 herbarium material. -

State of New York City's Plants 2018

STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 Daniel Atha & Brian Boom © 2018 The New York Botanical Garden All rights reserved ISBN 978-0-89327-955-4 Center for Conservation Strategy The New York Botanical Garden 2900 Southern Boulevard Bronx, NY 10458 All photos NYBG staff Citation: Atha, D. and B. Boom. 2018. State of New York City’s Plants 2018. Center for Conservation Strategy. The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY. 132 pp. STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 INTRODUCTION 10 DOCUMENTING THE CITY’S PLANTS 10 The Flora of New York City 11 Rare Species 14 Focus on Specific Area 16 Botanical Spectacle: Summer Snow 18 CITIZEN SCIENCE 20 THREATS TO THE CITY’S PLANTS 24 NEW YORK STATE PROHIBITED AND REGULATED INVASIVE SPECIES FOUND IN NEW YORK CITY 26 LOOKING AHEAD 27 CONTRIBUTORS AND ACKNOWLEGMENTS 30 LITERATURE CITED 31 APPENDIX Checklist of the Spontaneous Vascular Plants of New York City 32 Ferns and Fern Allies 35 Gymnosperms 36 Nymphaeales and Magnoliids 37 Monocots 67 Dicots 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report, State of New York City’s Plants 2018, is the first rankings of rare, threatened, endangered, and extinct species of what is envisioned by the Center for Conservation Strategy known from New York City, and based on this compilation of The New York Botanical Garden as annual updates thirteen percent of the City’s flora is imperiled or extinct in New summarizing the status of the spontaneous plant species of the York City. five boroughs of New York City. This year’s report deals with the City’s vascular plants (ferns and fern allies, gymnosperms, We have begun the process of assessing conservation status and flowering plants), but in the future it is planned to phase in at the local level for all species. -

Hsgcfellowshipbooklet V24 SU14-S15.Pdf

Summer 2014 – Spring 2015 HSGC Report Number 15-24 Compiled in 2015 by HAWAI‘I SPACE GRANT CONSORTIUM The Hawai‘i Space Grant Consortium is one of the fifty-two National Space Grant Colleges supported by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). Material in this volume may be copied for library, abstract service, education, or personal research; however, republication of any paper or portion thereof requires the written permission of the authors as well as appropriate acknowledgment of this publication. This report may be cited as Hawai‘i Space Grant Consortium (2015) Undergraduate Fellowship Reports. HSGC Report No. 15-24. Hawai‘i Space Grant Consortium, Honolulu. Individual articles may be cited as Author, A.B. (2015) Title of article. Undergraduate Fellowship Reports, pp. xx-xx. Hawai‘i Space Grant Consortium, Honolulu. This report is distributed by: Hawai‘i Space Grant Consortium Hawai‘i Institute of Geophysics and Planetology University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa 1680 East West Road, POST 501 Honolulu, HI 96822 Table of Contents Foreword………………………………………………………………………………… i REPORTS RADIO FREQUENCY OVER OPTICAL FIBER DESIGN AND IMPLEMENTATION FOR THE EXAVOLT ANTENNA …………………………….……………………….. 1 James L. Bynes III University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa DIGITAL IMAGERY AND GEOLOGIC MAP OF CHEGEM CALDERA, RUSSIA …9 Christina N. Cauley Unversity of Hawai‘i at Hilo DESIGN OF A WIRELESS POWER TRANSFER SYSTEM UTILIZING MICROWAVE FREQUENCIES ……..……………………………………..………… 17 Steven S. Ewers University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa MULTI-WALLED CARBON NANOTUBE NANOFORESTS AS GAS DIFFUSION LAYERS FOR PROTON EXCHANGE MEMBRANE FUEL CELLS…..…………….25 Kathryn Hu University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa CORRECTING SPECTRAL DATA FROM EXTRAGALACTIC STAR-FORMING REGIONS FOR ATMOSPHERIC DISPERSION………………………………………34 Casey M. -

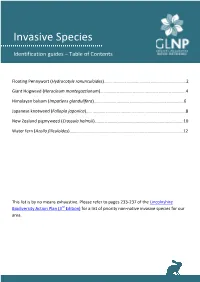

Invasive Species Identification Guide

Invasive Species Identification guides – Table of Contents Floating Pennywort (Hydrocotyle ranunculoides)……………………………….…………………………………2 Giant Hogweed (Heracleum mantegazzianum)…………………………………………………………………….4 Himalayan balsam (Impatiens glandulifera)………………………………………………………….…………….6 Japanese knotweed (Fallopia japonica)………………………………………………………………………………..8 New Zealand pigmyweed (Crassula helmsii)……………………………………………………………………….10 Water fern (Azolla filiculoides)……………………………………………………………………………………………12 This list is by no means exhaustive. Please refer to pages 233-237 of the Lincolnshire Biodiversity Action Plan (3rd Edition) for a list of priority non-native invasive species for our area. Floating pennywort Hydrocotyle ranunculoides Invasive species identification guide Where is it found? Floating on the surface or emerging from still or slowly moving freshwater. Can be free floating or rooted. Similar to…… Marsh pennywort (see bottom left photo) – this has a smaller more rounded leaf that attaches to the stem in the centre rather than between two lobes. Will always be rooted and never free floating. Key features Lobed leaves Fleshy green or red stems Floating or rooted Forms dense interwoven mats Leaf Leaves can be up to 7cm in diameter. Lobed leaves can float on or stand above the water. Marsh pennywort Roots Up to 5cm Fine white Stem attaches in roots centre More rounded leaf Floating pennywort Larger lobed leaf Stem attaches between lobes Photos © GBNNSS Workstream title goes here Invasive species ID guide: Floating pennywort Management Floating pennywort is extremely difficult to control due to rapid growth rates (up to 20cm from the bank each day). Chemical control: Can use glyphosphate but plant does not rot down very quickly after treatment so vegetation should be removed after two to three weeks in flood risk areas. Regular treatment necessary throughout the growing season. -

Maine Coefficient of Conservatism

Coefficient of Coefficient of Scientific Name Common Name Nativity Conservatism Wetness Abies balsamea balsam fir native 3 0 Abies concolor white fir non‐native 0 Abutilon theophrasti velvetleaf non‐native 0 3 Acalypha rhomboidea common threeseed mercury native 2 3 Acer ginnala Amur maple non‐native 0 Acer negundo boxelder non‐native 0 0 Acer pensylvanicum striped maple native 5 3 Acer platanoides Norway maple non‐native 0 5 Acer pseudoplatanus sycamore maple non‐native 0 Acer rubrum red maple native 2 0 Acer saccharinum silver maple native 6 ‐3 Acer saccharum sugar maple native 5 3 Acer spicatum mountain maple native 6 3 Acer x freemanii red maple x silver maple native 2 0 Achillea millefolium common yarrow non‐native 0 3 Achillea millefolium var. borealis common yarrow non‐native 0 3 Achillea millefolium var. millefolium common yarrow non‐native 0 3 Achillea millefolium var. occidentalis common yarrow non‐native 0 3 Achillea ptarmica sneezeweed non‐native 0 3 Acinos arvensis basil thyme non‐native 0 Aconitum napellus Venus' chariot non‐native 0 Acorus americanus sweetflag native 6 ‐5 Acorus calamus calamus native 6 ‐5 Actaea pachypoda white baneberry native 7 5 Actaea racemosa black baneberry non‐native 0 Actaea rubra red baneberry native 7 3 Actinidia arguta tara vine non‐native 0 Adiantum aleuticum Aleutian maidenhair native 9 3 Adiantum pedatum northern maidenhair native 8 3 Adlumia fungosa allegheny vine native 7 Aegopodium podagraria bishop's goutweed non‐native 0 0 Coefficient of Coefficient of Scientific Name Common Name Nativity -

Impatiens Glandulifera

NOBANIS – Invasive Alien Species Fact Sheet Impatiens glandulifera Author of this fact sheet: Harry Helmisaari, SYKE (Finnish Environment Institute), P.O. Box 140, FIN-00251 Helsinki, Finland, Phone + 358 20 490 2748, E-mail: [email protected] Bibliographical reference – how to cite this fact sheet: Helmisaari, H. (2010): NOBANIS – Invasive Alien Species Fact Sheet – Impatiens glandulifera. – From: Online Database of the European Network on Invasive Alien Species – NOBANIS www.nobanis.org, Date of access x/x/201x. Species description Scientific name: Impatiens glandulifera Royle (Balsaminaceae). Synonyms: Impatiens roylei Walpers. Common names: Himalayan balsam, Indian balsam, Policeman's Helmet (GB), Drüsiges Springkraut, Indisches Springkraut (DE), kæmpe-balsamin (DK), verev lemmalts (EE), jättipalsami (FI), risalísa (IS), bitinė sprigė (LT), puķu sprigane (LV), Reuzenbalsemien (NL), kjempespringfrø (NO), Niecierpek gruczolowaty, Niecierpek himalajski (PL), недотрога железконосная (RU), jättebalsamin (SE). Fig. 1 and 2. Impatiens glandulifera in an Alnus stand in Helsinki, Finland, and close-up of the seed capsules, photos by Terhi Ryttäri and Harry Helmisaari. Fig. 3 and 4. White and red flowers of Impatiens glandulifera, photos by Harry Helmisaari. Species identification Impatiens glandulifera is a tall annual with a smooth, usually hollow and jointed stem, which is easily broken (figs. 1-4). The stem can reach a height of 3 m and its diameter can be up to several centimetres. The leaves are opposite or in whorls of 3, glabrous, lanceolate to elliptical, 5-18 cm long and 2.5-7 cm wide. The inflorescences are racemes of 2-14 flowers that are 25-40 mm long. Flowers are zygomorphic, their lowest sepal forming a sac that ends in a straight spur. -

Plant Rank List.Xlsx

FAMILY SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME S RANK Aceraceae Acer ginnala Amur Maple SNA Aceraceae Acer negundo Manitoba Maple S5 Aceraceae Acer negundo var. interius Manitoba Maple S5 Aceraceae Acer negundo var. negundo Manitoba Maple SU Aceraceae Acer negundo var. violaceum Manitoba Maple SU Aceraceae Acer pensylvanicum Striped Maple SNA Aceraceae Acer rubrum Red Maple SNA Aceraceae Acer spicatum Mountain Maple S5 Acoraceae Acorus americanus Sweet Flag S5 Acoraceae Acorus calamus Sweet‐flag SNA Adoxaceae Adoxa moschatellina Moschatel S1 Alismataceae Alisma gramineum Narrow‐leaved Water‐plantain S1 Alismataceae Alisma subcordatum Common Water‐plantain SNA Alismataceae Alisma triviale Common Water‐plantain S5 Alismataceae Sagittaria cuneata Arum‐leaved Arrowhead S5 Alismataceae Sagittaria latifolia Broad‐leaved Arrowhead S4S5 Alismataceae Sagittaria rigida Sessile‐fruited Arrowhead S2 Amaranthaceae Amaranthus albus Tumble Pigweed SNA Amaranthaceae Amaranthus blitoides Prostrate Pigweed SNA Amaranthaceae Amaranthus hybridus Smooth Pigweed SNA Amaranthaceae Amaranthus retroflexus Redroot Pigweed SNA Amaranthaceae Amaranthus spinosus Thorny Amaranth SNA Amaranthaceae Amaranthus tuberculatus Rough‐fruited water‐hemp SU Anacardiaceae Rhus glabra Smooth Sumac S4 Anacardiaceae Toxicodendron rydbergii Poison‐ivy S5 Apiaceae Aegopodium podagraria Goutweed SNA Apiaceae Anethum graveolens Dill SNA Apiaceae Carum carvi Caraway SNA Apiaceae Cicuta bulbifera Bulb‐bearing Water‐hemlock S5 Apiaceae Cicuta maculata Water‐hemlock S5 Apiaceae Cicuta virosa Mackenzie's -

EYE EMPIRE Announces Extensive Fall Touring Plans with NONPOINT, SEETHER, and More

For Immediate Release August 13, 2012 EYE EMPIRE Announces Extensive Fall Touring Plans with NONPOINT, SEETHER, and More New Album ‘Impact’ – In Stores Now! American hard rockers EYE EMPIRE recently joined up with Nonpoint on a tour of several Eastern states that will travel through the end of August. The band will then continue on with a headline tour of several Southern states across the U.S., ultimately linking up with Seether from October 5th through the latter part of the month. See below for all current tour dates. Corey Lowery (Dark New Day, Stereomud, Stuck Mojo) and B.C. Kochmit (Dark New Day, Switched) formed EYE EMPIRE in 2007 with a rotating line-up of drummers—a spot now permanently filled by Ryan Bennett, formerly of Texas Hippie Coalition. In 2009, Donald Carpenter (formerly of Submersed) joined the band as the vocalist. Their latest release, a double album entitled Impact, was released in June 2012 and contains several tracks from the band’s self-released 2011 album, Moment of Impact, plus unreleased, acoustic, and live versions of songs. Several songs on Impact were recorded with Sevendust drummer Morgan Rose, and the track ‘Victim (Of The System)’ features guest vocals from Lajon Witherspoon, also of Sevendust. EYE EMPIRE has posted a video for the track ‘I Pray’ on their official YouTube page consisting of band-filmed footage, as well as an official album trailer. Head to this location to get a good taste of the band’s sound and subscribe to the page to receive EETV video updates and more! Catch EYE EMPIRE on tour now! -

Music Globally Protected Marks List (GPML) Music Brands & Music Artists

Music Globally Protected Marks List (GPML) Music Brands & Music Artists © 2012 - DotMusic Limited (.MUSIC™). All Rights Reserved. DotMusic reserves the right to modify this Document .This Document cannot be distributed, modified or reproduced in whole or in part without the prior expressed permission of DotMusic. 1 Disclaimer: This GPML Document is subject to change. Only artists exceeding 1 million units in sales of global digital and physical units are eligible for inclusion in the GPML. Brands are eligible if they are globally-recognized and have been mentioned in established music trade publications. Please provide DotMusic with evidence that such criteria is met at [email protected] if you would like your artist name of brand name to be included in the DotMusic GPML. GLOBALLY PROTECTED MARKS LIST (GPML) - MUSIC ARTISTS DOTMUSIC (.MUSIC) ? and the Mysterians 10 Years 10,000 Maniacs © 2012 - DotMusic Limited (.MUSIC™). All Rights Reserved. DotMusic reserves the right to modify this Document .This Document 10cc can not be distributed, modified or reproduced in whole or in part 12 Stones without the prior expressed permission of DotMusic. Visit 13th Floor Elevators www.music.us 1910 Fruitgum Co. 2 Unlimited Disclaimer: This GPML Document is subject to change. Only artists exceeding 1 million units in sales of global digital and physical units are eligible for inclusion in the GPML. 3 Doors Down Brands are eligible if they are globally-recognized and have been mentioned in 30 Seconds to Mars established music trade publications. Please -

How Does Genome Size Affect the Evolution of Pollen Tube Growth Rate, a Haploid Performance Trait?

Manuscript bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/462663; this version postedClick April here18, 2019. to The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv aaccess/download;Manuscript;PTGR.genome.evolution.15April20 license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Effects of genome size on pollen performance 2 3 4 5 How does genome size affect the evolution of pollen tube growth rate, a haploid 6 performance trait? 7 8 9 10 11 John B. Reese1,2 and Joseph H. Williams2 12 Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN 13 37996, U.S.A. 14 15 16 17 1Author for correspondence: 18 John B. Reese 19 Tel: 865 974 9371 20 Email: [email protected] 21 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/462663; this version posted April 18, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 22 ABSTRACT 23 Premise of the Study – Male gametophytes of most seed plants deliver sperm to eggs via a 24 pollen tube. Pollen tube growth rates (PTGRs) of angiosperms are exceptionally rapid, a pattern 25 attributed to more effective haploid selection under stronger pollen competition. Paradoxically, 26 whole genome duplication (WGD) has been common in angiosperms but rare in gymnosperms. -

Guidebook to Invasive Nonnative Plants of the Elwha Watershed Restoration

Guidebook to Invasive Nonnative Plants of the Elwha Watershed Restoration Olympic National Park, Washington Cynthia Lee Riskin A project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Environmental Horticulture University of Washington 2013 Committee: Linda Chalker-Scott Kern Ewing Sarah Reichard Joshua Chenoweth Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Environmental and Forest Sciences Guidebook to Invasive Nonnative Plants of the Elwha Watershed Restoration Olympic National Park, Washington Cynthia Lee Riskin Master of Environmental Horticulture candidate School of Environmental and Forest Sciences University of Washington, Seattle September 3, 2013 Contents Figures ................................................................................................................................................................. ii Tables ................................................................................................................................................................. vi Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................... vii Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 Bromus tectorum L. (BROTEC) ..................................................................................................................... 19 Cirsium arvense (L.) Scop. (CIRARV)