Is the Spread of Non-Native Plants in Alaska Accelerating?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Impatiens Glandulifera (Himalayan Balsam) Chloroplast Genome Sequence As a Promising Target for Populations Studies

Impatiens glandulifera (Himalayan balsam) chloroplast genome sequence as a promising target for populations studies Giovanni Cafa1, Riccardo Baroncelli2, Carol A. Ellison1 and Daisuke Kurose1 1 CABI Europe, Egham, Surrey, UK 2 University of Salamanca, Instituto Hispano-Luso de Investigaciones Agrarias (CIALE), Villamayor (Salamanca), Spain ABSTRACT Background: Himalayan balsam Impatiens glandulifera Royle (Balsaminaceae) is a highly invasive annual species native of the Himalayas. Biocontrol of the plant using the rust fungus Puccinia komarovii var. glanduliferae is currently being implemented, but issues have arisen with matching UK weed genotypes with compatible strains of the pathogen. To support successful biocontrol, a better understanding of the host weed population, including potential sources of introductions, of Himalayan balsam is required. Methods: In this molecular study, two new complete chloroplast (cp) genomes of I. glandulifera were obtained with low coverage whole genome sequencing (genome skimming). A 125-year-old herbarium specimen (HB92) collected from the native range was sequenced and assembled and compared with a 2-year-old specimen from UK field plants (HB10). Results: The complete cp genomes were double-stranded molecules of 152,260 bp (HB92) and 152,203 bp (HB10) in length and showed 97 variable sites: 27 intragenic and 70 intergenic. The two genomes were aligned and mapped with two closely related genomes used as references. Genome skimming generates complete organellar genomes with limited technical and financial efforts and produces large datasets compared to multi-locus sequence typing. This study demonstrates the 26 July 2019 Submitted suitability of genome skimming for generating complete cp genomes of historic Accepted 12 February 2020 Published 24 March 2020 herbarium material. -

Vascular Plants at Fort Ross State Historic Park

19005 Coast Highway One, Jenner, CA 95450 ■ 707.847.3437 ■ [email protected] ■ www.fortross.org Title: Vascular Plants at Fort Ross State Historic Park Author(s): Dorothy Scherer Published by: California Native Plant Society i Source: Fort Ross Conservancy Library URL: www.fortross.org Fort Ross Conservancy (FRC) asks that you acknowledge FRC as the source of the content; if you use material from FRC online, we request that you link directly to the URL provided. If you use the content offline, we ask that you credit the source as follows: “Courtesy of Fort Ross Conservancy, www.fortross.org.” Fort Ross Conservancy, a 501(c)(3) and California State Park cooperating association, connects people to the history and beauty of Fort Ross and Salt Point State Parks. © Fort Ross Conservancy, 19005 Coast Highway One, Jenner, CA 95450, 707-847-3437 .~ ) VASCULAR PLANTS of FORT ROSS STATE HISTORIC PARK SONOMA COUNTY A PLANT COMMUNITIES PROJECT DOROTHY KING YOUNG CHAPTER CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY DOROTHY SCHERER, CHAIRPERSON DECEMBER 30, 1999 ) Vascular Plants of Fort Ross State Historic Park August 18, 2000 Family Botanical Name Common Name Plant Habitat Listed/ Community Comments Ferns & Fern Allies: Azollaceae/Mosquito Fern Azo/la filiculoides Mosquito Fern wp Blechnaceae/Deer Fern Blechnum spicant Deer Fern RV mp,sp Woodwardia fimbriata Giant Chain Fern RV wp Oennstaedtiaceae/Bracken Fern Pleridium aquilinum var. pubescens Bracken, Brake CG,CC,CF mh T Oryopteridaceae/Wood Fern Athyrium filix-femina var. cyclosorum Western lady Fern RV sp,wp Dryopteris arguta Coastal Wood Fern OS op,st Dryopteris expansa Spreading Wood Fern RV sp,wp Polystichum munitum Western Sword Fern CF mh,mp Equisetaceae/Horsetail Equisetum arvense Common Horsetail RV ds,mp Equisetum hyemale ssp.affine Common Scouring Rush RV mp,sg Equisetum laevigatum Smooth Scouring Rush mp,sg Equisetum telmateia ssp. -

Review with Checklist of Fabaceae in the Herbarium of Iraq Natural History Museum

Review with checklist of Fabaceae in the herbarium of Iraq natural history museum Khansaa Rasheed Al-Joboury * Iraq Natural History Research Center and Museum, University of Baghdad, Baghdad, Iraq. GSC Biological and Pharmaceutical Sciences, 2021, 14(03), 137–142 Publication history: Received on 08 February 2021; revised on 10 March 2021; accepted on 12 March 2021 Article DOI: https://doi.org/10.30574/gscbps.2021.14.3.0074 Abstract This study aimed to make an inventory of leguminous plants for the purpose of identifying the plants that were collected over long periods and stored in the herbarium of Iraq Natural History Museum. It was found that the herbarium contains a large and varied number of plants from different parts of Iraq and in different and varied environments. It was collected and arranged according to a specific system in the herbarium to remain an important source for all graduate students and researchers to take advantage of these plants. Also, the flowering and fruiting periods of these plants in Iraq were recorded for different regions. Most of these plants begin to flower in the spring and thrive in fields and farms. Keywords: Fabaceae; Herbarium; Iraq; Natural; History; Museum 1. Introduction Leguminosae, Fabaceae or Papilionaceae, which was called as legume, pea, or bean Family, belong to the Order of Fabales [1]. The Fabaceae family have 727 genera also 19,325 species, which contents herbs, shrubs, trees, and climbers [2]. The distribution of fabaceae family was variety especially in cold mountainous regions for Europe, Asia and North America, It is also abundant in Central Asia and is characterized by great economic importance. -

State of New York City's Plants 2018

STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 Daniel Atha & Brian Boom © 2018 The New York Botanical Garden All rights reserved ISBN 978-0-89327-955-4 Center for Conservation Strategy The New York Botanical Garden 2900 Southern Boulevard Bronx, NY 10458 All photos NYBG staff Citation: Atha, D. and B. Boom. 2018. State of New York City’s Plants 2018. Center for Conservation Strategy. The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY. 132 pp. STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 INTRODUCTION 10 DOCUMENTING THE CITY’S PLANTS 10 The Flora of New York City 11 Rare Species 14 Focus on Specific Area 16 Botanical Spectacle: Summer Snow 18 CITIZEN SCIENCE 20 THREATS TO THE CITY’S PLANTS 24 NEW YORK STATE PROHIBITED AND REGULATED INVASIVE SPECIES FOUND IN NEW YORK CITY 26 LOOKING AHEAD 27 CONTRIBUTORS AND ACKNOWLEGMENTS 30 LITERATURE CITED 31 APPENDIX Checklist of the Spontaneous Vascular Plants of New York City 32 Ferns and Fern Allies 35 Gymnosperms 36 Nymphaeales and Magnoliids 37 Monocots 67 Dicots 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report, State of New York City’s Plants 2018, is the first rankings of rare, threatened, endangered, and extinct species of what is envisioned by the Center for Conservation Strategy known from New York City, and based on this compilation of The New York Botanical Garden as annual updates thirteen percent of the City’s flora is imperiled or extinct in New summarizing the status of the spontaneous plant species of the York City. five boroughs of New York City. This year’s report deals with the City’s vascular plants (ferns and fern allies, gymnosperms, We have begun the process of assessing conservation status and flowering plants), but in the future it is planned to phase in at the local level for all species. -

Illinois Exotic Species List

Exotic Species in Illinois Descriptions for these exotic species in Illinois will be added to the Web page as time allows for their development. A name followed by an asterisk (*) indicates that a description for that species can currently be found on the Web site. This list does not currently name all of the exotic species in the state, but it does show many of them. It will be updated regularly with additional information. Microbes viral hemorrhagic septicemia Novirhabdovirus sp. West Nile virus Flavivirus sp. Zika virus Flavivirus sp. Fungi oak wilt Ceratocystis fagacearum chestnut blight Cryphonectria parasitica Dutch elm disease Ophiostoma novo-ulmi and Ophiostoma ulmi late blight Phytophthora infestans white-nose syndrome Pseudogymnoascus destructans butternut canker Sirococcus clavigignenti-juglandacearum Plants okra Abelmoschus esculentus velvet-leaf Abutilon theophrastii Amur maple* Acer ginnala Norway maple Acer platanoides sycamore maple Acer pseudoplatanus common yarrow* Achillea millefolium Japanese chaff flower Achyranthes japonica Russian knapweed Acroptilon repens climbing fumitory Adlumia fungosa jointed goat grass Aegilops cylindrica goutweed Aegopodium podagraria horse chestnut Aesculus hippocastanum fool’s parsley Aethusa cynapium crested wheat grass Agropyron cristatum wheat grass Agropyron desertorum corn cockle Agrostemma githago Rhode Island bent grass Agrostis capillaris tree-of-heaven* Ailanthus altissima slender hairgrass Aira caryophyllaea Geneva bugleweed Ajuga genevensis carpet bugleweed* Ajuga reptans mimosa -

Atlas of the Flora of New England: Fabaceae

Angelo, R. and D.E. Boufford. 2013. Atlas of the flora of New England: Fabaceae. Phytoneuron 2013-2: 1–15 + map pages 1– 21. Published 9 January 2013. ISSN 2153 733X ATLAS OF THE FLORA OF NEW ENGLAND: FABACEAE RAY ANGELO1 and DAVID E. BOUFFORD2 Harvard University Herbaria 22 Divinity Avenue Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138-2020 [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT Dot maps are provided to depict the distribution at the county level of the taxa of Magnoliophyta: Fabaceae growing outside of cultivation in the six New England states of the northeastern United States. The maps treat 172 taxa (species, subspecies, varieties, and hybrids, but not forms) based primarily on specimens in the major herbaria of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut, with most data derived from the holdings of the New England Botanical Club Herbarium (NEBC). Brief synonymy (to account for names used in standard manuals and floras for the area and on herbarium specimens), habitat, chromosome information, and common names are also provided. KEY WORDS: flora, New England, atlas, distribution, Fabaceae This article is the eleventh in a series (Angelo & Boufford 1996, 1998, 2000, 2007, 2010, 2011a, 2011b, 2012a, 2012b, 2012c) that presents the distributions of the vascular flora of New England in the form of dot distribution maps at the county level (Figure 1). Seven more articles are planned. The atlas is posted on the internet at http://neatlas.org, where it will be updated as new information becomes available. This project encompasses all vascular plants (lycophytes, pteridophytes and spermatophytes) at the rank of species, subspecies, and variety growing independent of cultivation in the six New England states. -

Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Redwood National Park

Humboldt State University Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University Botanical Studies Open Educational Resources and Data 9-17-2018 Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Redwood National Park James P. Smith Jr Humboldt State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/botany_jps Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Smith, James P. Jr, "Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Redwood National Park" (2018). Botanical Studies. 85. https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/botany_jps/85 This Flora of Northwest California-Checklists of Local Sites is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Educational Resources and Data at Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Botanical Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CHECKLIST OF THE VASCULAR PLANTS OF THE REDWOOD NATIONAL & STATE PARKS James P. Smith, Jr. Professor Emeritus of Botany Department of Biological Sciences Humboldt State Univerity Arcata, California 14 September 2018 The Redwood National and State Parks are located in Del Norte and Humboldt counties in coastal northwestern California. The national park was F E R N S established in 1968. In 1994, a cooperative agreement with the California Department of Parks and Recreation added Del Norte Coast, Prairie Creek, Athyriaceae – Lady Fern Family and Jedediah Smith Redwoods state parks to form a single administrative Athyrium filix-femina var. cyclosporum • northwestern lady fern unit. Together they comprise about 133,000 acres (540 km2), including 37 miles of coast line. Almost half of the remaining old growth redwood forests Blechnaceae – Deer Fern Family are protected in these four parks. -

Invasive Species Identification Guide

Invasive Species Identification guides – Table of Contents Floating Pennywort (Hydrocotyle ranunculoides)……………………………….…………………………………2 Giant Hogweed (Heracleum mantegazzianum)…………………………………………………………………….4 Himalayan balsam (Impatiens glandulifera)………………………………………………………….…………….6 Japanese knotweed (Fallopia japonica)………………………………………………………………………………..8 New Zealand pigmyweed (Crassula helmsii)……………………………………………………………………….10 Water fern (Azolla filiculoides)……………………………………………………………………………………………12 This list is by no means exhaustive. Please refer to pages 233-237 of the Lincolnshire Biodiversity Action Plan (3rd Edition) for a list of priority non-native invasive species for our area. Floating pennywort Hydrocotyle ranunculoides Invasive species identification guide Where is it found? Floating on the surface or emerging from still or slowly moving freshwater. Can be free floating or rooted. Similar to…… Marsh pennywort (see bottom left photo) – this has a smaller more rounded leaf that attaches to the stem in the centre rather than between two lobes. Will always be rooted and never free floating. Key features Lobed leaves Fleshy green or red stems Floating or rooted Forms dense interwoven mats Leaf Leaves can be up to 7cm in diameter. Lobed leaves can float on or stand above the water. Marsh pennywort Roots Up to 5cm Fine white Stem attaches in roots centre More rounded leaf Floating pennywort Larger lobed leaf Stem attaches between lobes Photos © GBNNSS Workstream title goes here Invasive species ID guide: Floating pennywort Management Floating pennywort is extremely difficult to control due to rapid growth rates (up to 20cm from the bank each day). Chemical control: Can use glyphosphate but plant does not rot down very quickly after treatment so vegetation should be removed after two to three weeks in flood risk areas. Regular treatment necessary throughout the growing season. -

Trifolium Campestre Schreb., PNNATE HOP CLOVER

Vascular Plants of Williamson County Trifolium campestre − PINNATE HOP CLOVER [Fabaceae] Trifolium campestre Schreb., PNNATE HOP CLOVER. Annual, taprooted, initially rosetted, 1−several-stemmed at base, late-branching in canopy, ascending to spreading, in range to 35 cm tall; shoots initially with several basal leaves (absent at flowering) and several cauline leaves, soft-hairy; roots nodulated. Stems: cylindric, to 1 mm diameter, green, internodes to 50 mm long at midplant, with circular leaf scars at nodes, appressed-pilose with upward-pointing hairs. Leaves: helically alternate, pinnately 3-foliolate, petiolate without pulvinus, with stipules; stipules 2, not fused around stem, asymmetrically ovate, ± 6 × 3−4 mm, fused to petiole at least to midpoint, entire often wavy and ciliate on free margin, acute to short-acuminate at tip, ca. 10-veined from base, the veins green and tissue colorless between veins, surfaces glabrous, aging scarious and persistent; petiole above stipules channeled, slender and to 25 mm long, sparsely short-hairy; rachis channeled, 1.5−5 mm long, short-hairy; petiolules pulvinuslike, 0.5 mm long, light green, with several hairs; blades of leaflets subequal, symmetric, ovate, (4−)8−12(−16) × (4−)6−8 mm, terminal leaflet wider than lateral leaflets, broadly tapered at base, short-dentate from just below midblade, roundish to shallowly notched or subtruncate at tip, pinnately veined with evenly spaced, parallel lateral veins with veins ending in teeth, midrib slightly sunken on upper surface and raised on lower surface, -

Appendix C Plant and Animal Species Observed

Appendix C Plant and Animal Species Observed This list includes vascular plants, mammals, birds, reptiles, and amphibians observed in the BSA by biologists during various surveys in 2005 and 2006. This list does not include invertebrate species. Invertebrates that would be most commonly encountered on the site would include butterflies, flies, dragonflies, damselflies, beetles, earwigs, grasshoppers, crickets, termites, true bugs, mantids, lacewings, bees, wasps, ants, and spiders. PLANT SPECIES OBSERVED Scientific Name Common Name Invasive Plant Rating CLUB AND SPIKE MOSSES Selaginellaceae Spike moss family Selaginella cinerascens Mesa spikemoss TRUE FERNS Azollaceae Mosquito fern family Azolla filiculoides Pacific mosquito fern Marsileaceae Marsilea family Marsilea vestita Hairy waterclover Pilularia americana American pillwort Pteridaceae Lip fern family Pellaea andromedifolia Coffee fern Pentagramma triangularis Goldenback fern PINOPHYTA GYMNOSPERMS Cupressaceace Cypress family Juniperus californica California juniper DICOT FLOWERING PLANTS Aizoaceae Carpet weed family Carpobrotus edulis* Hottentot-fig HIGH Mesembryanthemum nodiflorum* Slender-leaved ice plant Trianthema portulacastrum Horse-purslane Amaranthaceae Amaranth family Amaranthus albus* Tumbling pigweed Amaranthus palmeri Palmer’s pigweed Amaranthus sp. Pigweed Anacardiaceae Sumac family Malosma laurina Laurel sumac Rhus ovata Sugar bush Rhus trilobata Skunkbush sumac Schinus molle* Peruvian pepper tree LIMITED Schinus terebinthifolius* Brazilian pepper tree LIMITED Mid -

Plant List for Web Page

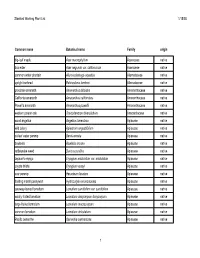

Stanford Working Plant List 1/15/08 Common name Botanical name Family origin big-leaf maple Acer macrophyllum Aceraceae native box elder Acer negundo var. californicum Aceraceae native common water plantain Alisma plantago-aquatica Alismataceae native upright burhead Echinodorus berteroi Alismataceae native prostrate amaranth Amaranthus blitoides Amaranthaceae native California amaranth Amaranthus californicus Amaranthaceae native Powell's amaranth Amaranthus powellii Amaranthaceae native western poison oak Toxicodendron diversilobum Anacardiaceae native wood angelica Angelica tomentosa Apiaceae native wild celery Apiastrum angustifolium Apiaceae native cutleaf water parsnip Berula erecta Apiaceae native bowlesia Bowlesia incana Apiaceae native rattlesnake weed Daucus pusillus Apiaceae native Jepson's eryngo Eryngium aristulatum var. aristulatum Apiaceae native coyote thistle Eryngium vaseyi Apiaceae native cow parsnip Heracleum lanatum Apiaceae native floating marsh pennywort Hydrocotyle ranunculoides Apiaceae native caraway-leaved lomatium Lomatium caruifolium var. caruifolium Apiaceae native woolly-fruited lomatium Lomatium dasycarpum dasycarpum Apiaceae native large-fruited lomatium Lomatium macrocarpum Apiaceae native common lomatium Lomatium utriculatum Apiaceae native Pacific oenanthe Oenanthe sarmentosa Apiaceae native 1 Stanford Working Plant List 1/15/08 wood sweet cicely Osmorhiza berteroi Apiaceae native mountain sweet cicely Osmorhiza chilensis Apiaceae native Gairdner's yampah (List 4) Perideridia gairdneri gairdneri Apiaceae -

Fort Ord Natural Reserve Plant List

UCSC Fort Ord Natural Reserve Plants Below is the most recently updated plant list for UCSC Fort Ord Natural Reserve. * non-native taxon ? presence in question Listed Species Information: CNPS Listed - as designated by the California Rare Plant Ranks (formerly known as CNPS Lists). More information at http://www.cnps.org/cnps/rareplants/ranking.php Cal IPC Listed - an inventory that categorizes exotic and invasive plants as High, Moderate, or Limited, reflecting the level of each species' negative ecological impact in California. More information at http://www.cal-ipc.org More information about Federal and State threatened and endangered species listings can be found at https://www.fws.gov/endangered/ (US) and http://www.dfg.ca.gov/wildlife/nongame/ t_e_spp/ (CA). FAMILY NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME LISTED Ferns AZOLLACEAE - Mosquito Fern American water fern, mosquito fern, Family Azolla filiculoides ? Mosquito fern, Pacific mosquitofern DENNSTAEDTIACEAE - Bracken Hairy brackenfern, Western bracken Family Pteridium aquilinum var. pubescens fern DRYOPTERIDACEAE - Shield or California wood fern, Coastal wood wood fern family Dryopteris arguta fern, Shield fern Common horsetail rush, Common horsetail, field horsetail, Field EQUISETACEAE - Horsetail Family Equisetum arvense horsetail Equisetum telmateia ssp. braunii Giant horse tail, Giant horsetail Pentagramma triangularis ssp. PTERIDACEAE - Brake Family triangularis Gold back fern Gymnosperms CUPRESSACEAE - Cypress Family Hesperocyparis macrocarpa Monterey cypress CNPS - 1B.2, Cal IPC