Universidade Federal Da Paraíba Centro De Ciências

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2010 16Th Annual SAG AWARDS

CATEGORIA CINEMA Melhor ator JEFF BRIDGES / Bad Blake - "CRAZY HEART" (Fox Searchlight Pictures) GEORGE CLOONEY / Ryan Bingham - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) COLIN FIRTH / George Falconer - "A SINGLE MAN" (The Weinstein Company) MORGAN FREEMAN / Nelson Mandela - "INVICTUS" (Warner Bros. Pictures) JEREMY RENNER / Staff Sgt. William James - "THE HURT LOCKER" (Summit Entertainment) Melhor atriz SANDRA BULLOCK / Leigh Anne Tuohy - "THE BLIND SIDE" (Warner Bros. Pictures) HELEN MIRREN / Sofya - "THE LAST STATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) CAREY MULLIGAN / Jenny - "AN EDUCATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) GABOUREY SIDIBE / Precious - "PRECIOUS: BASED ON THE NOVEL ‘PUSH’ BY SAPPHIRE" (Lionsgate) MERYL STREEP / Julia Child - "JULIE & JULIA" (Columbia Pictures) Melhor ator coadjuvante MATT DAMON / Francois Pienaar - "INVICTUS" (Warner Bros. Pictures) WOODY HARRELSON / Captain Tony Stone - "THE MESSENGER" (Oscilloscope Laboratories) CHRISTOPHER PLUMMER / Tolstoy - "THE LAST STATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) STANLEY TUCCI / George Harvey – “UM OLHAR NO PARAÍSO” ("THE LOVELY BONES") (Paramount Pictures) CHRISTOPH WALTZ / Col. Hans Landa – “BASTARDOS INGLÓRIOS” ("INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS") (The Weinstein Company/Universal Pictures) Melhor atriz coadjuvante PENÉLOPE CRUZ / Carla - "NINE" (The Weinstein Company) VERA FARMIGA / Alex Goran - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) ANNA KENDRICK / Natalie Keener - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) DIANE KRUGER / Bridget Von Hammersmark – “BASTARDOS INGLÓRIOS” ("INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS") (The Weinstein Company/Universal Pictures) MO’NIQUE / Mary - "PRECIOUS: BASED ON THE NOVEL ‘PUSH’ BY SAPPHIRE" (Lionsgate) Melhor elenco AN EDUCATION (Sony Pictures Classics) DOMINIC COOPER / Danny ALFRED MOLINA / Jack CAREY MULLIGAN / Jenny ROSAMUND PIKE / Helen PETER SARSGAARD / David EMMA THOMPSON / Headmistress OLIVIA WILLIAMS / Miss Stubbs THE HURT LOCKER (Summit Entertainment) CHRISTIAN CAMARGO / Col. John Cambridge BRIAN GERAGHTY / Specialist Owen Eldridge EVANGELINE LILLY / Connie James ANTHONY MACKIE / Sgt. -

Glee: Uma Transmedia Storytelling E a Construção De Identidades Plurais

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DA BAHIA INSTITUTO DE HUMANIDADES, ARTES E CIÊNCIAS PROGRAMA MULTIDISCIPLINAR DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM CULTURA E SOCIEDADE ROBERTO CARLOS SANTANA LIMA GLEE: UMA TRANSMEDIA STORYTELLING E A CONSTRUÇÃO DE IDENTIDADES PLURAIS Salvador 2012 ROBERTO CARLOS SANTANA LIMA GLEE: UMA TRANSMEDIA STORYTELLING E A CONSTRUÇÃO DE IDENTIDADES PLURAIS Dissertação apresentada ao Programa Multidisciplinar de Pós-graduação, Universidade Federal da Bahia, como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de mestre em Cultura e Sociedade, área de concentração: Cultura e Identidade. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Djalma Thürler Salvador 2012 Sistema de Bibliotecas - UFBA Lima, Roberto Carlos Santana. Glee : uma Transmedia storytelling e a construção de identidades plurais / Roberto Carlos Santana Lima. - 2013. 107 f. Inclui anexos. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Djalma Thürler. Dissertação (mestrado) - Universidade Federal da Bahia, Faculdade de Comunicação, Salvador, 2012. 1. Glee (Programa de televisão). 2. Televisão - Seriados - Estados Unidos. 3. Pluralismo cultural. 4. Identidade social. 5. Identidade de gênero. I. Thürler, Djalma. II. Universidade Federal da Bahia. Faculdade de Comunicação. III. Título. CDD - 791.4572 CDU - 791.233 TERMO DE APROVAÇÃO ROBERTO CARLOS SANTANA LIMA GLEE: UMA TRANSMEDIA STORYTELLING E A CONSTRUÇÃO DE IDENTIDADES PLURAIS Dissertação aprovada como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau de Mestre em Cultura e Sociedade, Universidade Federal da Bahia, pela seguinte banca examinadora: Djalma Thürler – Orientador ------------------------------------------------------------- -

The Artist Is the Athlete

Carmen Winant e Artist Is the Athlete Investigating Practice in Matthew Barney’s DRAWING RESTRAINT 1 –6 Introduction Picture this: in a small white room below the Yale University gymnasium, an undergraduate named Matthew Barney set up several video cameras on tripods. Wearing a loose gray tee shirt, sneakers, and worn-in jeans, the twenty year old is momentar - ily suspended on a ramp that leans steeply against the wall. Gripping an elongated drawing tool in his right hand, he forcibly strains against the self-imposed harness system that pulls him back, reaching toward the far wall with the weight of his body. In some attempts, he will suc - cessfully make his mark; in others, he’ll fall just short. is scene, equally desperate, fleeting, and captivating, constitutes DRAWING RE - STRAINT 2, one of the six studio experiments made by the artist be - tween 187 and 18. is essay will investigate the resonance of athletic experience in those early studio projects, which established the young Barney as an international art-world sensation, and will contend that recognizing the specific and paradoxical ritual of prac - tice—rather than the broader strokes of performance—inform a deeper understanding of these works. “Practice” can be a generic term carrying different meanings de - pending on the context and field of endeavor; most germane here are art practice and athletic practice. For a visual artist, the term “prac - tice” may encompass both an activity undertaken to develop one’s Carmen Winant mastery and the process of actually creating and completing a piece New Yorker profile (“His Body, Himself”), Barney hinted at the cen - intended for an audience or market. -

Mira, Royal Detective”

10 The Indian EXPRESS NORTH AMERICAN Newsline MARCH 13, 2020 Disney Jr, IAAC host special screening of “Mira, Royal Detective” OUR BUREau bers Roshni Edwards, Kamran Lucas, Karan New York Brar, Parvesh Cheena and Sonal Shah. Joining the previously announced cast isney Junior and the Indo-American in recurring and guest star roles are Kunal Arts Council (IAAC) hosted a special Nayyar (“The Big Bang Theory”), Danny Dadvance screening of upcoming ani- Pudi (Disney’s “DuckTales”), Iqbal Theba mated series “Mira, Royal Detective” on Sat- (“Glee”), Sunita Mani (“GLOW”), Karen Da- urday, February 22. Cast members including vid (“Fear the Walking Dead”), Rizwan Manji Kal Penn, Leela Ladnier, Aasif Mandvi and (“Perfect Harmony”), Hari Kondabolu (“To- Aparna Nancherla were in attendance. tally Biased with W. Kamau Bell”), Nardeep The animated series will premiere in the Khurmi (“Jane the Virgin”), Aarti Sequeira U.S. on FRIDAY, MARCH 20 (11:00 a.m. (“The Next Food Network Star”), Avantika EDT/PDT on Disney Channel and 7:00 p.m. Vandanapu (Disney+ Original Series “Diary EDT/PDT on Disney Junior). Disney Chan- of a Future President”), Julian Zane (Disney’s nel India will also be premiering a sneak- “Doc McStuffins”), Brian George (“The Big peek that same day, followed by the series Bang Theory”), Sakina Jaffrey (“House of premiere on Sunday, March 22. Set in the Cards”) and Madhur Jaffrey (“I Feel Bad”). magical Indian-inspired land of Jalpur, the “IAAC is proud to support and celebrate series introduces a brave and resourceful girl mated 160 countries on Disney Channel and Hannah Simone, Jameela Jamil, Aparna each member of this cast and applauds the named Mira, a commoner who is appointed Disney Junior platforms globally. -

As Heard on TV

Hugvísindasvið As Heard on TV A Study of Common Breaches of Prescriptive Grammar Rules on American Television Ritgerð til BA-prófs í Ensku Ragna Þorsteinsdóttir Janúar 2013 2 Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Enska As Heard on TV A Study of Common Breaches of Prescriptive Grammar Rules on American Television Ritgerð til BA-prófs í Ensku Ragna Þorsteinsdóttir Kt.: 080288-3369 Leiðbeinandi: Pétur Knútsson Janúar 2013 3 Abstract In this paper I research four grammar variables by watching three seasons of American television programs, aired during the winter of 2010-2011: How I Met Your Mother, Glee, and Grey’s Anatomy. For background on the history of prescriptive grammar, I discuss the grammarian Robert Lowth and his views on the English language in the 18th century in relation to the status of the language today. Some of the rules he described have become obsolete or were even considered more of a stylistic choice during the writing and editing of his book, A Short Introduction to English Grammar, so reviewing and revising prescriptive grammar is something that should be done regularly. The goal of this paper is to discover the status of the variables ―to lay‖ versus ―to lie,‖ ―who‖ versus ―whom,‖ ―X and I‖ versus ―X and me,‖ and ―may‖ versus ―might‖ in contemporary popular media, and thereby discern the validity of the prescriptive rules in everyday language. Every instance of each variable in the three programs was documented and attempted to be determined as correct or incorrect based on various rules. Based on the numbers gathered, the usage of three of the variables still conforms to prescriptive rules for the most part, while the word ―whom‖ has almost entirely yielded to ―who‖ when the objective is called for. -

The Glee News

Inside:The Times of Glee Fox to end ‘Glee’? Kurt Hummel recieves great reviews on his The co-creator of Fox’s great acting, sining, and “Glee” has revealed dancing in his debut “Funny Girl” star Rachel Berry is photographed on the streets of New York plans to end the series, role of “Peter Pan”. walking five dogs. She will soon drop the news about her dog adoption Us Weekly reports. Ryan event. Murphy told reporters Wednesday in L.A. that the musical series will New meaning to “dog eats end its run next year after six seasons. The end of the show ap- dog” business pears to be linked to the Rising actors Berry and Hummel host Brod- death of Cory Monteith, one of its stars. Chris Colfer expands way themed dog show In the streets of New York, happy to be giving back. “After the emotional his talent from simple the three-legged dog to the Rachel uncertainly leads mother and her son. The three friends share a memorial episode for an actor and musician a dozen dogs on leads group hug, happily. Monteith and his char- to a screenplay wiriter through the street. Blaine Sam suggests to Mercedes acter Finn Hudson aired and Artie have positioned that they give McCo- “Old Dog New Tricks” is as well. last week, Murphy said themselves among some naughey to someone at the written by Chris Colfer, who it’s been very difficult to event, but Mercedes tells lunching papparazi, and claims his “two favorite move on with the show,” him to not bother - they’re loudly announce her arriv- cording things in life are animals the story reports. -

US, JAPANESE, and UK TELEVISUAL HIGH SCHOOLS, SPATIALITY, and the CONSTRUCTION of TEEN IDENTITY By

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by British Columbia's network of post-secondary digital repositories BLOCKING THE SCHOOL PLAY: US, JAPANESE, AND UK TELEVISUAL HIGH SCHOOLS, SPATIALITY, AND THE CONSTRUCTION OF TEEN IDENTITY by Jennifer Bomford B.A., University of Northern British Columbia, 1999 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ENGLISH UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN BRITISH COLUMBIA August 2016 © Jennifer Bomford, 2016 ABSTRACT School spaces differ regionally and internationally, and this difference can be seen in television programmes featuring high schools. As television must always create its spaces and places on the screen, what, then, is the significance of the varying emphases as well as the commonalities constructed in televisual high school settings in UK, US, and Japanese television shows? This master’s thesis considers how fictional televisual high schools both contest and construct national identity. In order to do this, it posits the existence of the televisual school story, a descendant of the literary school story. It then compares the formal and narrative ways in which Glee (2009-2015), Hex (2004-2005), and Ouran koukou hosutobu (2006) deploy space and place to create identity on the screen. In particular, it examines how heteronormativity and gender roles affect the abilities of characters to move through spaces, across boundaries, and gain secure places of their own. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ii Table of Contents iii Acknowledgement v Introduction Orientation 1 Space and Place in Schools 5 Schools on TV 11 Schools on TV from Japan, 12 the U.S., and the U.K. -

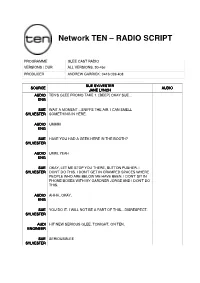

Network TEN – RADIO SCRIPT

Network TEN – RADIO SCRIPT PROGRAMME GLEE CAST RADIO VERSIONS / DUR ALL VERSIONS. 30-45s PRODUCER ANDREW GARRICK: 0416 026 408 SUE SYLVESTER SOURCE AUDIO JANE LYNCH AUDIO TEN'S GLEE PROMO TAKE 1. [BEEP] OKAY SUE… ENG SUE WAIT A MOMENT…SNIFFS THE AIR. I CAN SMELL SYLVESTER SOMETHING IN HERE. AUDIO UMMM ENG SUE HAVE YOU HAD A GEEK HERE IN THE BOOTH? SYLVESTER AUDIO UMM, YEAH ENG SUE OKAY, LET ME STOP YOU THERE, BUTTON PUSHER. I SYLVESTER DON'T DO THIS. I DON'T GET IN CRAMPED SPACES WHERE PEOPLE WHO ARE BELOW ME HAVE BEEN. I DON'T SIT IN PHONE BOXES WITH MY GARDNER JORGE AND I DON'T DO THIS. AUDIO AHHH..OKAY. ENG SUE YOU DO IT. I WILL NOT BE A PART OF THIS…DISRESPECT. SYLVESTER AUDI HIT NEW SERIOUS GLEE. TONIGHT, ON TEN. ENGINEER SUE SERIOUSGLEE SYLVESTER Network TEN – RADIO SCRIPT FINN HUDSON SOURCE AUDIO CORY MONTEITH FEMALE TEN'S GLEE PROMO TAKE 1. [BEEP] AUDIO ENG FINN OKAY. THANKS. HI AUSTRALIA, IT'S FINN HUSON HERE, HUDSON FROM TEN'S NEW SHOW GLEE. FEMALE IT'S REALLY GREAT, AND I CAN ONLY TELL YOU THAT IT'S FINN COOL TO BE A GLEEK. I'M A GLEEK, YOU SHOULD BE TOO. HUDSON FEMALE OKAY, THAT'S PRETTY GOOD FINN. CAN YOU MAYBE DO IT AUDIO WITH YOUR SHIRT OFF? ENG FINN WHAT? HUDSON FEMALE NOTHING. AUDIO ENG FINN OKAY… HUDSON FEMALE MAYBE JUST THE LAST LINE AUDIO ENG FINN OKAY. UMM. GLEE – 730 TONIGHT, ON TEN. SERIOUSGLEE HUDSON FINN OKAY. -

14. Swan Song

LISA K. PERDIGAO 14. SWAN SONG The Art of Letting Go in Glee In its five seasons, the storylines of Glee celebrate triumph over adversity. Characters combat what they perceive to be their limitations, discovering their voices and senses of self in New Directions. Tina Cohen-Chang overcomes her shyness, Kurt Hummel embraces his individuality and sexuality, Finn Hudson discovers that his talents extend beyond the football field, Rachel Berry finds commonality with a group instead of remaining a solo artist, Mike Chang is finally allowed to sing, and Artie Abrams is able to transcend his physical disabilities through his performances.1 But perhaps where Glee most explicitly represents the theme of triumph over adversity is in the series’ evasion of death. The threat of death appears in the series, oftentimes in the form of the all too real threats present in a high school setting: car accidents (texting while driving), school shootings, bullying, and suicide. As Artie is able to escape his wheelchair to dance in an elaborate sequence, if only in a dream, the characters are able to avoid the reality of death and part of the adolescent experience and maturation into adulthood. As Trites (2000) states, “For many adolescents, trying to understand death is as much of a rite of passage as experiencing sexuality is” (p. 117). However, Glee is forced to alter its plot in season five. The season begins with a real-life crisis for the series; actor Cory Monteith’s death is a devastating loss for the actors, writers, and producers as well as the series itself. -

Five Bright Starrs in Baylor's Future

WE’RE THERE WHEN YOU CAN’T BE TheMONDAY | AUGUST 20, 2012Baylor Lariatwww.baylorlariat.com SPORTS Page B1 NEWS Page A6 MOVIES Page B9 O-line stands tall New stadium start ‘Bourne Legacy’ or born lousy? See what Richardson, Baker, Wade, Floyd Casey houses historic An interesting look at why the new flick Kaufold, and Drango have in store memories, but plans for John Eddie fails to follow suit with director Robert for the 2012 football season. Williams Field ignite fan fervor. Ludlum’s box-office-busting triology. Vol. 114 No. 1 © 2012, Baylor University In Print Five bright Starrs in Baylor’s future >>HATS OFF TO ALUM Baylor law graduate, Kevin By Amando Dominick Reynolds, directs Emmy aspirational statement says that it is very Staff Writer important,” Davis said. “The value of a Bay- nominated miniseries. lor education can be supported through di- Page B8 A new university vision promises to be versity of revenue stream.” the next stepping stone in Baylor’s path to Included in the first aspirational state- the future. ment is the goal “to approach the profile >>NBA-BOUND BEARS Pro Futuris, meaning ‘for the future,’ is See where Miller, Acy, and of Carnegie’s research universites with the name of Baylor’s newest strategic vi- very high research activity,” by produc- Jones III are headed from here! sion, created to guide the university’s path ing more Ph.D.s according to the Baylor Page B4 in the coming years, website. Baylor is currently classified Adopted unanimously by the Baylor as a research university with high re- >>DISCOVERY STRIDES Board of Regents on May 11, this vision search activity. -

Queer Identities and Glee

IDENTITY AND SOLIDARITY IN ONLINE COMMUNITIES: QUEER IDENITIES AND GLEE Katie M. Buckley A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music August 2014 Committee: Katherine Meizel, Advisor Kara Attrep Megan Rancier © 2014 Katie Buckley All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine Meizel, Advisor Glee, a popular FOX television show that began airing in 2009, has continuously pushed the limits of what is acceptable on American television. This musical comedy, focusing on a high school glee club, incorporates numerous stereotypes and real-world teenage struggles. This thesis focuses on the queer characteristics of four female personalities: Santana, Brittany, Coach Beiste, and Coach Sue. I investigate how their musical performances are producing a constructive form of mass media by challenging hegemonic femininity through camp and by producing relatable queer female role models. In addition, I take an ethnographic approach by examining online fan blogs from the host site Tumblr. By reading the blogs as a digital archive and interviewing the bloggers, I show the positive and negative effects of an online community and the impact this show has had on queer girls, allies, and their worldviews. iv This work is dedicated to any queer human being who ever felt alone as a teenager. v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to extend my greatest thanks to my teacher and advisor, Dr. Meizel, for all of her support through the writing of this thesis and for always asking the right questions to keep me thinking. I would also like to thank Dr. -

CINE MEJOR ACTOR JEFF BRIDGES / Bad Blake

CINE MEJOR ACTOR JEFF BRIDGES / Bad Blake - "CRAZY HEART" (Fox Searchlight Pictures) GEORGE CLOONEY / Ryan Bingham - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) COLIN FIRTH / George Falconer - "A SINGLE MAN" (The Weinstein Company) MORGAN FREEMAN / Nelson Mandela - "INVICTUS" (Warner Bros. Pictures) JEREMY RENNER / Staff Sgt. William James - "THE HURT LOCKER" (Summit Entertainment) MEJOR ACTRIZ SANDRA BULLOCK / Leigh Anne Tuohy - "THE BLIND SIDE" (Warner Bros. Pictures) HELEN MIRREN / Sofya - "THE LAST STATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) CAREY MULLIGAN / Jenny - "AN EDUCATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) GABOUREY SIDIBE / Precious - "PRECIOUS: BASED ON THE NOVEL ‘PUSH’ BY SAPPHIRE" (Lionsgate) MERYL STREEP / Julia Child - "JULIE & JULIA" (Columbia Pictures) MEJOR ACTOR DE REPARTO MATT DAMON / Francois Pienaar - "INVICTUS" (Warner Bros. Pictures) WOODY HARRELSON / Captain Tony Stone - "THE MESSENGER" (Oscilloscope Laboratories) CHRISTOPHER PLUMMER / Tolstoy - "THE LAST STATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) STANLEY TUCCI / George Harvey - "THE LOVELY BONES" (Paramount Pictures) CHRISTOPH WALTZ / Col. Hans Landa - "INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS" (The Weinstein Company/Universal Pictures) MEJOR ACTRIZ DE REPARTO PENÉLOPE CRUZ / Carla - "NINE" (The Weinstein Company) VERA FARMIGA / Alex Goran - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) ANNA KENDRICK / Natalie Keener - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) DIANE KRUGER / Bridget Von Hammersmark - "INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS" (The Weinstein Company/Universal Pictures) MO’NIQUE / Mary - "PRECIOUS: BASED ON THE NOVEL ‘PUSH’ BY SAPPHIRE" (Lionsgate) MEJOR ELENCO AN EDUCATION (Sony Pictures Classics) DOMINIC COOPER / Danny ALFRED MOLINA / Jack CAREY MULLIGAN / Jenny ROSAMUND PIKE / Helen PETER SARSGAARD / David EMMA THOMPSON / Headmistress OLIVIA WILLIAMS / Miss Stubbs THE HURT LOCKER (Summit Entertainment) CHRISTIAN CAMARGO / Col. John Cambridge BRIAN GERAGHTY / Specialist Owen Eldridge EVANGELINE LILLY / Connie James ANTHONY MACKIE / Sgt. J.T.