Lateline/Content/2015/S4359818.Htm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

US and Kurdish Forces Keep Iraqi Northern

MENU Policy Analysis / Articles & Op-Eds U.S. and Kurdish Forces Keep Iraqi Northern Front Stable by Soner Cagaptay Apr 7, 2003 ABOUT THE AUTHORS Soner Cagaptay Soner Cagaptay is the Beyer Family fellow and director of the Turkish Research Program at The Washington Institute. Articles & Testimony he northern front was supposed to have been occupied by tens of thousands of U.S. troops who would make up T the second front of a pincer movement against Baghdad. But Turkey's refusal to allow American forces and heavy armor to cross the Turkish-Iraqi frontier means that only a few thousand moderately armed allied soldiers are now engaging Saddam Hussein's troops in the north. And fighting along side the allies are lightly armed Kurdish forces. Although the revised allied campaign in the north has been successful, many analysts believe that the original plan might have backfired. While there's little doubt that American tanks rolling across northern Iraq toward Baghdad would shorten the war, it also might have opened the door for Turkey to send large numbers of troops into Kurdish- controlled territory -- igniting a conflict between Turks and Kurds. "I guess we have everything to be thankful for the fact all hell did not break lose in the north," says Charles Pena, Director of Defense Policy Studies at the Cato Institute here in Washington. "The Turks showed some restraint and did not come across the border, really in large numbers. And the Kurds did likewise show restraint. So that, combined with the fact that the Iraqi forces in the north don't seem very interested in engaging in offensive operations means that the north has stayed relatively stable. -

The Independent Review

Volume 20, Number 1 Spring 2010 Unemployment Then and Now by William F. Shughart II* n March of 1933, when Mobilizing America for global war, outfitting Ithe Great Depression had youngsters of the so-called Greatest Generation driven the U.S. economy to with military uniforms, equipping them with M-1 rock bottom, the unemploy- rifles and sending many ment rate stood at 25 per- to die in France’s hedge- cent: One in four Americans rows or the South Pacific’s who had jobs in 1929 were jungles not only lowered queuing on bread lines rather than the overall unemploy- working on assembly lines. ment rate dramatically, The unemployment rate remained but also drew millions of at historically high levels throughout women into the workforce the following decade. De- to help manufacture the spite massive increases armaments that, in some in federal government cases, would maim or kill their fathers, spending under the husbands, and sons. programs of President Why did unemployment persist af- Roosevelt’s New Deal, ter FDR took the oath of office in March 14 percent of the labor 1933 pledging to end Herbert Hoover’s perceived force still had no jobs indifference to the visible economic hardships vis- in 1941. Unemployment ited on hordes of his fellow citizens, epitomized did not fall into single digits until after Pearl by General Douglas MacArthur’s brutal routing Harbor, when millions of men were drafted into of the “Bonus Army” gathered on the mudflats of the armed forces to fight the first axis of evil. Anacostia? Didn’t the alphabet soup of work relief programs the president subsequently launched— * William F. -

CFC Afghanistan Newsletter

07 October 2009 Afghanistan Review This document is intended to provide an overview of relevant sector events in Afghanistan from 30 September -06 October 2009. More comprehensive information is available on the Civil- Military Overview (CMO) at www.cimicweb.org.1 Inside This Issue Letters to the Editor: Jonathan Hadaway, [email protected] /+1 757-683-4233: Letters to the Editor In Focus Dear Sir, if the US does not agree to General McChrystal's troop increase (Reference: Economic Stabilization 30 September 2009 CFC Afghanistan Review, „In Focus‟) it will undermine a crucial, first step in counterinsurgency: showing the population that you have the will to win. Governance & Participation Counterinsurgency operations require additional troops. The necessary focus, Humanitarian Assistance resources, strategy and troops have yet to be dedicated to Afghanistan. I think a new strategy with the required number of military forces deserves a chance to succeed. Infrastructure Justice & Reconciliation --Jesse Wilson, United States Central Command (CENTCOM) Security Social Well-Being Response to Last Week‟s Question In Focus: Eide vs. Galbraith Jonathan Hadaway, [email protected] /+1 757-683-4233: Question of the Week Is it more important for The Deputy United Nations Special Representative of the Secretary General (DSRSG) the United Nations to was removed from his post following a „private-turned-public‟ spat with his superior at fully support free, fair, the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA). -

Endgame—Lessons from Srebrenica (PDF)

Session 4 Endgame – Lessons from Srebrenica Documents List Page Date Author Title Source Notes No. 4-1 13-Jul-1995 Christopher Next Steps in Bosnia State Department // Archive FOIA 4-4 17-Jul-1995 Block Bodies Pile Up in Horror The of Srebrenica Independent (newspaper) 4-5 13-Jul-1995 U.S. National Group of People: ICTY Geospatial Sandici, Bosnia and Intelligence Herzegovina Agency 4-5 14-Jul-1995 Studio B [Piles of Bodies] Studio B Broadcast on Serb TV 4-6 14-Jul-1995 Mladic Meeting with President USHMM Mladic Milosevic, Bildt, and Files General de la Presle 4-7 17-Jul-1995 Akashi Meeting in Belgrade ICTY excerpt from original document (page 1-2 of 3) 4-9 18-Jul-1995 Annan Human Rights ICTY Violations by Bosnian Serbs 4-10 19-Jul-1995 Shattuck Defense of the Safe US State excerpt from original Areas in Bosnia Department document (page 1-2 of 3) Online Reading Room 4-12 19-Jul-1995 Akashi Disposition of Displaced ICTY Persons from Srebrenica 4-14 25-Jul-2015 Vershbow Massacres at Srebrenica Clinton Library // Archive FOIA 4-17 26-Jul-1995 Baxter Meeting Notes General ICTY Smith / General Mladic 25 July 4-19 4-Aug-1995 Shattuck Bosnia Trip Report US State Department Online Reading Room 4-21 11-Aug-1995 Albright Croatia, Bosnia: Amb Dept of State // excerpt from original Albright Briefs Security Archive FOIA document (page 2-3 of 6) Council on Possible Mass Graves Near Srebrenica... *Box around text denotes portion of document highlighted for conference discussion. 4-23 13-Jul-1995 U.S. -

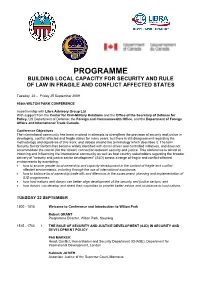

Programme Building Local Capacity for Security and Rule of Law in Fragile and Conflict Affected States

PROGRAMME BUILDING LOCAL CAPACITY FOR SECURITY AND RULE OF LAW IN FRAGILE AND CONFLICT AFFECTED STATES Tuesday 22 – Friday 25 September 2009 958th WILTON PARK CONFERENCE In partnership with Libra Advisory Group Ltd With support from the Center for Civil-Military Relations and the Office of the Secretary of Defense for Policy, US Department of Defense; the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, and the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada. Conference Objectives The international community has been involved in attempts to strengthen the provision of security and justice in developing, conflict-affected and fragile states for many years; but there is still disagreement regarding the methodology and objectives of this work, and debate around the terminology which describes it. The term Security Sector Reform has become widely identified with donor-driven and controlled initiatives, and does not accommodate the crucial (for the citizen) connection between security and justice. This conference is aimed at informing and influencing the international community as well as host country stakeholders regarding the broader delivery of "security and justice sector development" (SJD) across a range of fragile and conflict-affected environments by examining: how to ensure greater local ownership and capacity development in the context of fragile and conflict- affected environments, including through the use of international assistance; how to balance local ownership trade-offs and dilemmas in the assessment, planning and implementation of SJD programmes; how host nations and donors can better align development of the security and justice sectors; and how donors can develop and direct their capacities to provide better advice and assistance to host nations. -

Peacemaking: Success on the Danube Region of Croatia the Erdut Agreement

chapter 11 Peacemaking: Success on the Danube Region of Croatia The Erdut Agreement The Erdut Agreement for the Danube region of Croatia was one of the great successes of United Nations peacemaking in the former Yugoslavia. Thorvald Stoltenberg is the undoubted father of this agreement. icfy’s main efforts on Croatia had been to put down building blocks for peace one by one and to help work out autonomy regimes for the Croatian Serbs that would guarantee them respect for internationally respected stan- dards of human rights and the rights of minorities. Great credit for the drafting of such a regime must go to our dear departed friend Paul Szasz, who bore the brunt of the drafting of this and many other documents in his capacity as Legal Adviser to the International Conference on the Former Yugoslavia. This effort to work out a regime of autonomy for the Croatian Serbs would come to naught in the end. Tudjman clearly wanted no part of it because he wanted full integration of the Serbs inside a unitary Croatia. As for Milosevic, when the plan was first presented to him and he had studied it, he told Stoltenberg and Owen, “Gentlemen, please do not ruin today ideas that might work in five years time in the future.” He also had other ideas in mind and prob- ably wanted to negotiate with Tudjman an exchange of territory in which he would incorporate into Serbia especially the eastern enclave which was sepa- rated from Serbia merely by a river. icfy, without a doubt, made foundation contributions to the building of peace in Croatia. -

Union Calendar No. 450 105Th Congress, 2D Session – – – – – – – – – – – – House Report 105–804

1 Union Calendar No. 450 105th Congress, 2d Session ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± House Report 105±804 INVESTIGATION INTO IRANIAN ARMS SHIPMENTS TO BOSNIA R E P O R T OF THE PERMANENT SELECT COMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES TOGETHER WITH MINORITY AND ADDITIONAL VIEWS OCTOBER 9, 1998.ÐCommitted to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 69±006 WASHINGTON : 1998 LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, PERMANENT SELECT COMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE, Washington, DC, October 9, 1998. Hon. NEWT GINGRICH, Speaker of the House, U.S. Capitol, Washington, DC. DEAR MR. SPEAKER: Pursuant to the Rules of the House, I am pleased to transmit herewith an investigative report of the Perma- nent Select Committee on Intelligence, styled ``Investigation into Iranian Arms Shipments to Bosnia.'' The report includes findings and conclusions, as well as minority and additional views. The Committee's report was approved by a majority of the Per- manent Select Committee on Intelligence on August 6, 1998. Sincerely yours, PORTER J. GOSS, Chairman. (III) Union Calendar No. 450 105TH CONGRESS REPORT 2d Session HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 105±804 "! INVESTIGATION INTO IRANIAN ARMS SHIPMENTS TO BOSNIA OCTOBER 9, 1998.ÐCommitted to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed Mr. GOSS, from the Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, submitted the following REPORT together with MINORITY AND ADDITIONAL VIEWS [To accompany ] OVERVIEW On April 5, 1996, the Los Angeles Times published an article, ``U.S. OKd Iran Arms for Bosnia, Officials say,'' alleging that in 1994, the Clinton Administration gave a ``green light'' for Iranian arms shipments to Bosnia to transit Croatia. -

United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan: Background and Policy Issues

United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan: Background and Policy Issues Rhoda Margesson Specialist in International Humanitarian Policy December 27, 2010 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R40747 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan: Background and Policy Issues Summary The United Nations (UN) has had an active presence in Afghanistan since 1988, and it is highly regarded by many Afghans for playing a brokering role in ending the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan. As a result of the Bonn Agreement of December 2001, coordinating international donor activity and assistance have been tasked to a United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA). However, there are other coordinating institutions tied to the Afghan government, and UNAMA has struggled to exercise its full mandate. The international recovery and reconstruction effort in Afghanistan is immense and complicated and, in coordination with the Afghan government, involves U.N. agencies, bilateral donors, international organizations, and local and international non-governmental organizations (NGOs). The coordinated aid programs of the United States and its European allies focus on a wide range of activities, from strengthening the central and local governments of Afghanistan and its security forces to promoting civilian reconstruction, reducing corruption, and assisting with elections. Some of the major issues UNAMA is wrestling with include the following: • Most observers agree that continued, substantial, long-term development is key, as is the need for international support, but questions have been raised about corruption, aid effectiveness (funds required, priorities established, impact received), and the coordination necessary to achieve sufficient improvement throughout the country. -

Parker House, Boston, Massachusetts December 12, 1977

American politics and in the Democratic party. The son of a bricklayer from County Cork, O'Neill was born in Cambridge in 1912, attended St. John's High and was MARY PEROT NICHOLS, Communications Director, Office THE HONORABLE SUSAN SLOANE, Assistant Attorney graduated from Boston College in 1936. of the Mayor, Boston, Ma. General, Division of Public Charities, Commonwealth of JACKIE O'NEILL, Assistant to Vice President for Govern- Massachusetts, Boston, Ma. In that same year, he was elected to the Massachusetts ment and Community Affairs, Harvard University, HERBERT SOSTEK, Executive Vice President, Gibbs Oil House of Representatives. He was elected Minority Cambridge, Ma. Company, Revere, Ma. Leader in 1947 and became Speaker in 1948. In 1952, MICHAEL O'NEILL, Stockbroker, Buttonwood Security, THE HONORABLE CHRIS SPIRO, Minority Leader, New O'Neill was elected to the Congressional seat being va- Boston, Ma. Hampshire General Court, Concord, N. H. cated by John F. Kennedy. In Washington, he became a THE HONORABLE THOMAS P. O'NEILL, JR., Speaker, CHRISTINE SULLIVAN, Appointments Secretary to the member of the Rules Committee and was later chosen United States House of Representatives, Washington, D. C. Speaker, United States House of Representatives, Washing- Majority Whip and Majority Leader. In 1941, he married MARTY NOLAN, Washington Bureau Chief, the Boston ton, D. C. the former Mildred Anne Miller. They have five chil- Globe; Harvard Fellow, Institute of Politics, J. F. K. School KATHLEEN SULLIVAN, President, Boston School Com- dren. of Government, Harvard University, Cambridge, Ma. mittee, Boston, Ma. Parker House, Boston, Massachusetts HAROLD PACHIOS, Attorney, Portland, Me. THE HONORABLE JAMES TIERNEY, Majority Floor In January of this year, he was elected Speaker of the THE HONORABLE LOIS PINES, State Representative, Leader, State of Maine, Augusta, Me. -

Fareed's Briefing Book

BX FAREED’S BRIEFING BOOK 04-11-2010 PETER GALBRAITH Peter Galbraith Peter Galbraith is an author, academic, commentator, policy advisor and former United States diplomat. He is a senior diplomatic fellow at the Center for Arms Control and Non- Proliferation. He is also the son of John Kenneth Galbraith, one of the leading economists of the 20th century. Galbraith holds degrees from the Commonwealth School, Harvard College, Oxford University and Georgetown University Law Center. He was an assistant professor of Social Relations at Windham College in Putney, Vermont, from 1975 to 1978 and later became Professor of National Security Strategy at the National War College. From 1979-1993, Galbraith served on the staff of the US Senate Foreign Relations Committee. He left when he was appointed the first U.S. Ambassador to Croatia by President Bill Clinton in 1993. As ambassador, he was co-mediator and principal architect of the 1995 Erdut Agreement that ended the war in that country. In 2003, Galbraith resigned from U.S. government after 24 years of service. For several years after, he acted as an advisor to the Kurdistan Regional Government in northern Iraq as it wrote its Constitution. On March 25, 2009, Galbraith was announced as the next UN Deputy Special Representative for Afghanistan. He helped expose the massive fraud that took place in the 2009 Afghanistan Presidential Elections. After a dispute over the handling of the Afghan election, Galbraith abruptly left the country in mid September 2009. At that time, his financial interest in oil fields in Iraq's Kurdish region became public. -

Putting Legitimacy at the Center of Foreign Operations and Assistance

Putting State Legitimacy at the Center of Foreign Operations and Assistance BY BRUCE GILLEY t is a commonly expressed idea that a key goal of intervention in and assistance to foreign nations is to establish (or re-establish) legitimate political authority. Historically, even so Igreat a skeptic as John Stuart Mill allowed that intervention could be justified if it were “for the good of the people themselves” as measured by their willingness to support and defend the results.1 In recent times, President George W. Bush justified his post-war emphasis on democracy- building in Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere in the Middle East with the logic that “nations in the region will have greater stability because governments will have greater legitimacy.”2 President Obama applauded French intervention in Mali for its ability “to reaffirm democracy and legiti- macy and an effective government” in the country.3 The experiences of Western-led state reconstruction in Cambodia, Kosovo, Afghanistan, and Iraq among other places have been characterized by a belated recognition of the legitimacy imper- ative. In contemporary debates on a wide range of foreign intervention and assistance operations, legitimacy has come to occupy a central place in discussions of the domestic agenda of rebuilding that follows the external agenda that drives the initial intervention – stopping genocide, toppling a dictator, saving the starving, or establishing a transitional authority. Today, we take the rebuilding of domestic legitimacy so much for granted in our assumptions about foreign intervention and assistance that we often hurry onto the details. But it is worth pondering the question of legitimacy as an explicit aim of any foreign operation – military, eco- nomic, or civil – rather than one that we assume will automatically follow from doing a range of good deeds. -

Peter Galbraith, Democrat Interview: July 26, 2016

Peter Galbraith, Democrat Interview: July 26, 2016 1. Addressing Statewide Issues Like many other states, Vermont faces many economic and social issues. We also know that 85% of Vermonters agree that arts and culture are vital to their community’s life. • Can you provide examples on how you would integrate the arts, culture, and creative community in solving social problems (or in enhancing opportunities for greater social or civic engagement)? • How would you use the creative sector to drive economic development across the state? Peter Galbraith: Well, perhaps a word of background. In 1958, my father wrote a book called “The Affluent Society,” which challenged the conventional wisdom. That was a phrase that he actually invented. The conventional wisdom was that our well-being is measured simply by GNP: by how much we produce, of goods and services. He argued for other values as well and notably, protecting the environment and the arts. This has been part of the Galbraith family philosophy my entire life, or almost my entire life. It seems to me that the arts are an integral part of our life. Culture is everything. You walk down State Street and you come to this building and you have around it, a little sculpture garden with flowers. Art is something that belongs in public spaces. It’s something that is very appropriate with museums and places that people can visit and in public buildings. Theatrical performances are also part of the fabric of community. To me, it’s just integral to all aspects of life and not just here in Vermont.