Co-Evolution of Tumor and Immune Cells During Progression of Multiple Myeloma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents (PDF)

July 26, 2011 u vol. 108 u no. 30 u 12187–12560 Cover image: Pictured is a Tasmanian devil (Sarcophilus harrisii), a carnivorous marsupial whose numbers are dwindling due to an infectious facial cancer called Devil Facial Tumor Disease. Webb Miller et al. sequenced the genome of devils from northwest and south- east Tasmania, spanning the range of this threatened species on the Australian island. The authors report that the sequences reveal a worrisome dearth of genetic diversity among devils, suggesting the need for genetically characterized stocks to help breed hardier devils that might be better equipped to fight diseases. See the article by Miller et al. on pages 12348–12353. Image courtesy of Stephan C. Schuster. From the Cover 12348 Decoding the Tasmanian devil genome 12283 Illuminating chromosomal architecture 12295 Symmetry of cultured cells 12319 Caloric restriction and infertility 12366 Genetic diversity among ants Contents COMMENTARIES 12189 Methyl fingerprinting of the nucleosome reveals the molecular mechanism of high-mobility group THIS WEEK IN PNAS nucleosomal-2 (HMGN2) association Catherine A. Musselman and Tatiana G. Kutateladze See companion article on page 12283 12187 In This Issue 12191 Examining the establishment of cellular axes using intrinsic chirality LETTERS (ONLINE ONLY) Jason C. McSheene and Rebecca D. Burdine See companion article on page 12295 E341 Difference between restoring and predicting 3D 12193 Secrets of palm oil biosynthesis revealed structures of the loops in G-protein–coupled Toni Voelker receptors by molecular modeling See companion article on page 12527 Gregory V. Nikiforovich, Christina M. Taylor, Garland R. Marshall, and Thomas J. Baranski E342 Reply to Nikiforovich et al.: Restoration of the loop regions of G-protein–coupled receptors Dahlia A. -

Table S1 the Four Gene Sets Derived from Gene Expression Profiles of Escs and Differentiated Cells

Table S1 The four gene sets derived from gene expression profiles of ESCs and differentiated cells Uniform High Uniform Low ES Up ES Down EntrezID GeneSymbol EntrezID GeneSymbol EntrezID GeneSymbol EntrezID GeneSymbol 269261 Rpl12 11354 Abpa 68239 Krt42 15132 Hbb-bh1 67891 Rpl4 11537 Cfd 26380 Esrrb 15126 Hba-x 55949 Eef1b2 11698 Ambn 73703 Dppa2 15111 Hand2 18148 Npm1 11730 Ang3 67374 Jam2 65255 Asb4 67427 Rps20 11731 Ang2 22702 Zfp42 17292 Mesp1 15481 Hspa8 11807 Apoa2 58865 Tdh 19737 Rgs5 100041686 LOC100041686 11814 Apoc3 26388 Ifi202b 225518 Prdm6 11983 Atpif1 11945 Atp4b 11614 Nr0b1 20378 Frzb 19241 Tmsb4x 12007 Azgp1 76815 Calcoco2 12767 Cxcr4 20116 Rps8 12044 Bcl2a1a 219132 D14Ertd668e 103889 Hoxb2 20103 Rps5 12047 Bcl2a1d 381411 Gm1967 17701 Msx1 14694 Gnb2l1 12049 Bcl2l10 20899 Stra8 23796 Aplnr 19941 Rpl26 12096 Bglap1 78625 1700061G19Rik 12627 Cfc1 12070 Ngfrap1 12097 Bglap2 21816 Tgm1 12622 Cer1 19989 Rpl7 12267 C3ar1 67405 Nts 21385 Tbx2 19896 Rpl10a 12279 C9 435337 EG435337 56720 Tdo2 20044 Rps14 12391 Cav3 545913 Zscan4d 16869 Lhx1 19175 Psmb6 12409 Cbr2 244448 Triml1 22253 Unc5c 22627 Ywhae 12477 Ctla4 69134 2200001I15Rik 14174 Fgf3 19951 Rpl32 12523 Cd84 66065 Hsd17b14 16542 Kdr 66152 1110020P15Rik 12524 Cd86 81879 Tcfcp2l1 15122 Hba-a1 66489 Rpl35 12640 Cga 17907 Mylpf 15414 Hoxb6 15519 Hsp90aa1 12642 Ch25h 26424 Nr5a2 210530 Leprel1 66483 Rpl36al 12655 Chi3l3 83560 Tex14 12338 Capn6 27370 Rps26 12796 Camp 17450 Morc1 20671 Sox17 66576 Uqcrh 12869 Cox8b 79455 Pdcl2 20613 Snai1 22154 Tubb5 12959 Cryba4 231821 Centa1 17897 -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

2016 Joint Meeting Program

April 15 – 17, 2016 Fairmont Chicago Millennium Park • Chicago, Illinois The AAP/ASCI/APSA conference is jointly provided by Boston University School of Medicine and AAP/ASCI/APSA. Meeting Program and Abstracts www.jointmeeting.org www.jointmeeting.org Special Events at the 2016 AAP/ASCI/APSA Joint Meeting Friday, April 15 Saturday, April 16 ASCI President’s Reception ASCI Food and Science Evening 6:15 – 7:15 p.m. 6:30 – 9:00 p.m. Gold Room The Mid-America Club, Aon Center ASCI Dinner & New Member AAP Member Banquet Induction Ceremony (Ticketed guests only) (Ticketed guests only) 7:00 – 10:00 p.m. 7:30 – 9:45 p.m. Imperial Ballroom, Level B2 Rouge, Lobby Level How to Solve a Scientific Puzzle: Speaker: Clara D. Bloomfield, MD Clues from Stockholm and Broadway The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center Speaker: Joe Goldstein, MD APSA Welcome Reception & University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas Presidential Address APSA Dinner (Ticketed guests only) 9:00 p.m. – Midnight Signature Room, 360 Chicago, 7:30 – 9:00 p.m. John Hancock Center (off-site) Rouge, Lobby Level Speaker: Daniel DelloStritto, APSA President Finding One’s Scientific Niche: Musings from a Clinical Neuroscientist Speaker: Helen Mayberg, MD, Emory University Dessert Reception (open to all attendees) 10:00 p.m. – Midnight Imperial Foyer, Level B2 Sunday, April 17 APSA Future of Medicine and www.jointmeeting.org Residency Luncheon Noon – 2:00 p.m. Rouge, Lobby Level 2 www.jointmeeting.org Program Contents General Program Information 4 Continuing Medical Education Information 5 Faculty and Speaker Disclosures 7 Scientific Program Schedule 9 Speaker Biographies 16 Call for Nominations: 2017 Harrington Prize for Innovation in Medicine 26 AAP/ASCI/APSA Joint Meeting Faculty 27 Award Recipients 29 Call for Nominations: 2017 Harrington Scholar-Innovator Award 31 Call for Nominations: George M. -

Supplementary Data

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA A cyclin D1-dependent transcriptional program predicts clinical outcome in mantle cell lymphoma Santiago Demajo et al. 1 SUPPLEMENTARY DATA INDEX Supplementary Methods p. 3 Supplementary References p. 8 Supplementary Tables (S1 to S5) p. 9 Supplementary Figures (S1 to S15) p. 17 2 SUPPLEMENTARY METHODS Western blot, immunoprecipitation, and qRT-PCR Western blot (WB) analysis was performed as previously described (1), using cyclin D1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-753, RRID:AB_2070433) and tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich, T5168, RRID:AB_477579) antibodies. Co-immunoprecipitation assays were performed as described before (2), using cyclin D1 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-8396, RRID:AB_627344) or control IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-2025, RRID:AB_737182) followed by protein G- magnetic beads (Invitrogen) incubation and elution with Glycine 100mM pH=2.5. Co-IP experiments were performed within five weeks after cell thawing. Cyclin D1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-753), E2F4 (Bethyl, A302-134A, RRID:AB_1720353), FOXM1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-502, RRID:AB_631523), and CBP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-7300, RRID:AB_626817) antibodies were used for WB detection. In figure 1A and supplementary figure S2A, the same blot was probed with cyclin D1 and tubulin antibodies by cutting the membrane. In figure 2H, cyclin D1 and CBP blots correspond to the same membrane while E2F4 and FOXM1 blots correspond to an independent membrane. Image acquisition was performed with ImageQuant LAS 4000 mini (GE Healthcare). Image processing and quantification were performed with Multi Gauge software (Fujifilm). For qRT-PCR analysis, cDNA was generated from 1 µg RNA with qScript cDNA Synthesis kit (Quantabio). qRT–PCR reaction was performed using SYBR green (Roche). -

HER2 Gene Signatures: (I) Novel and (Ii) Established by Desmedt Et Al 2008 (31)

Table S1: HER2 gene signatures: (i) Novel and (ii) Established by Desmedt et al 2008 (31). Pearson R [neratinib] is the correlation with neratinib response using a pharmacogenomic model of breast cancer cell lines (accessed online via CellMinerCDB). *indicates significantly correlated genes. n/a = data not available in CellMinerCDB Genesig N Gene ID Pearson R [neratinib] p-value (i) Novel 20 ERBB2 0.77 1.90E-08* SPDEF 0.45 4.20E-03* TFAP2B 0.2 0.24 CD24 0.38 0.019* SERHL2 0.41 0.0097* CNTNAP2 0.12 0.47 RPL19 0.29 0.073 CAPN13 0.51 1.00E-03* RPL23 0.22 0.18 LRRC26 n/a n/a PRODH 0.42 9.00E-03* GPRC5C 0.44 0.0056* GGCT 0.38 1.90E-02* CLCA2 0.31 5.70E-02 KDM5B 0.33 4.20E-02* SPP1 -0.25 1.30E-01 PHLDA1 -0.54 5.30E-04* C15orf48 0.06 7.10E-01 SUSD3 -0.09 5.90E-01 SERPINA1 0.14 4.10E-01 (ii) Established 24 ERBB2 0.77 1.90E-08* PERLD1 0.77 1.20E-08* PSMD3 0.33 0.04* PNMT 0.33 4.20E-02* GSDML 0.4 1.40E-02* CASC3 0.26 0.11 LASP1 0.32 0.049* WIPF2 0.27 9.70E-02 EPN3 0.42 8.50E-03* PHB 0.38 0.019* CLCA2 0.31 5.70E-02 ORMDL2 0.06 0.74 RAP1GAP 0.53 0.00059* CUEDC1 0.09 0.61 HOXC11 0.2 0.23 CYP2J2 0.45 0.0044* HGD 0.14 0.39 ABCA12 0.07 0.67 ATP2C2 0.42 0.0096* ITGA3 0 0.98 CEACAM5 0.4 0.012* TMEM16K 0.15 0.37 NR1D1 n/a n/a SNX7 -0.28 0.092 FJX1 -0.26 0.12 KCTD9 -0.11 0.53 PCTK3 -0.04 0.83 CREG1 0.17 0.3 Table S2: Up-regulated genes from the top 500 DEGs for each comparison by WAD score METABRIC METABRIC METABRIC TCGA ERBB2amp ERBB2mut oncERBB2mut HER2+ ERBB2 PIP ANKRD30A ERBB2 GRB7 CYP4Z1 CYP4Z1 SCGB2A2 PGAP3 PROM1 LRRC26 SPDEF GSDMB CD24 PPP1R1B FOXA1 -

Supplemental Data.Pdf

Table S1. Summary of sequencing results A. DNase‐seq data % Align % Mismatch % >=Q30 bases Sample ID # Reads % unique reads (PF) Rate (PF) (PF) WT_1 84,301,522 86.76 0.52 93.34 96.30 WT_2 98,744,222 84.97 0.51 93.75 89.94 Hmgn1‐/‐_1 79,620,656 83.94 0.86 90.58 88.65 Hmgn1‐/‐_2 62,673,782 84.13 0.87 91.30 89.18 Hmgn2‐/‐_1 87,734,440 83.49 0.71 91.81 90.00 Hmgn2‐/‐_2 82,498,808 83.25 0.69 92.73 90.66 Hmgn1‐/‐n2‐/‐_1 71,739,638 68.51 2.31 81.11 89.22 Hmgn1‐/‐n2‐/‐_2 74,113,682 68.19 2.37 81.16 86.57 B. ChIP‐seq data Histone % Align % Mismatch % >=Q30 % unique Genotypes # Reads marks (PF) Rate (PF) bases (PF) reads H3K4me1 100670054 92.99 0.28 91.21 87.29 H3K4me3 67064272 91.97 0.35 89.11 27.15 WT H3K27ac 90,340,242 93.57 0.28 95.02 89.80 input 111,292,572 78.24 0.55 96.07 86.99 H3K4me1 84598176 92.34 0.33 91.2 81.69 H3K4me3 90032064 92.19 0.44 88.76 15.81 Hmgn1‐/‐n2‐/‐ H3K27ac 86,260,526 93.40 0.29 94.94 87.49 input 78,142,334 78.47 0.56 95.82 81.11 C. MNase‐seq data % Mismatch % >=Q30 bases % unique Sample ID # Reads % Align (PF) Rate (PF) (PF) reads WT_1_Extensive 45,232,694 55.23 1.49 90.22 81.73 WT_1_Limited 105,460,950 58.03 1.39 90.81 79.62 WT_2_Extensive 40,785,338 67.34 1.06 89.76 89.60 WT_2_Limited 105,738,078 68.34 1.05 90.29 85.96 Hmgn1‐/‐n2‐/‐_1_Extensive 117,927,050 55.74 1.49 89.50 78.01 Hmgn1‐/‐n2‐/‐_1_Limited 61,846,742 63.76 1.22 90.57 84.55 Hmgn1‐/‐n2‐/‐_2_Extensive 137,673,830 60.04 1.30 89.28 78.99 Hmgn1‐/‐n2‐/‐_2_Limited 45,696,614 62.70 1.21 90.71 85.52 D. -

Curcumin Alters Gene Expression-Associated DNA Damage, Cell Cycle, Cell Survival and Cell Migration and Invasion in NCI-H460 Human Lung Cancer Cells in Vitro

ONCOLOGY REPORTS 34: 1853-1874, 2015 Curcumin alters gene expression-associated DNA damage, cell cycle, cell survival and cell migration and invasion in NCI-H460 human lung cancer cells in vitro I-TSANG CHIANG1,2, WEI-SHU WANG3, HSIN-CHUNG LIU4, SU-TSO YANG5, NOU-YING TANG6 and JING-GUNG CHUNG4,7 1Department of Radiation Oncology, National Yang‑Ming University Hospital, Yilan 260; 2Department of Radiological Technology, Central Taiwan University of Science and Technology, Taichung 40601; 3Department of Internal Medicine, National Yang‑Ming University Hospital, Yilan 260; 4Department of Biological Science and Technology, China Medical University, Taichung 404; 5Department of Radiology, China Medical University Hospital, Taichung 404; 6Graduate Institute of Chinese Medicine, China Medical University, Taichung 404; 7Department of Biotechnology, Asia University, Taichung 404, Taiwan, R.O.C. Received March 31, 2015; Accepted June 26, 2015 DOI: 10.3892/or.2015.4159 Abstract. Lung cancer is the most common cause of cancer CARD6, ID1 and ID2 genes, associated with cell survival and mortality and new cases are on the increase worldwide. the BRMS1L, associated with cell migration and invasion. However, the treatment of lung cancer remains unsatisfactory. Additionally, 59 downregulated genes exhibited a >4-fold Curcumin has been shown to induce cell death in many human change, including the DDIT3 gene, associated with DNA cancer cells, including human lung cancer cells. However, the damage; while 97 genes had a >3- to 4-fold change including the effects of curcumin on genetic mechanisms associated with DDIT4 gene, associated with DNA damage; the CCPG1 gene, these actions remain unclear. Curcumin (2 µM) was added associated with cell cycle and 321 genes with a >2- to 3-fold to NCI-H460 human lung cancer cells and the cells were including the GADD45A and CGREF1 genes, associated with incubated for 24 h. -

Supplementary Methods

Supplementary methods Human lung tissues and tissue microarray (TMA) All human tissues were obtained from the Lung Cancer Specialized Program of Research Excellence (SPORE) Tissue Bank at the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center (Houston, TX). A collection of 26 lung adenocarcinomas and 24 non-tumoral paired tissues were snap-frozen and preserved in liquid nitrogen for total RNA extraction. For each tissue sample, the percentage of malignant tissue was calculated and the cellular composition of specimens was determined by histological examination (I.I.W.) following Hematoxylin-Eosin (H&E) staining. All malignant samples retained contained more than 50% tumor cells. Specimens resected from NSCLC stages I-IV patients who had no prior chemotherapy or radiotherapy were used for TMA analysis by immunohistochemistry. Patients who had smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime were defined as smokers. Samples were fixed in formalin, embedded in paraffin, stained with H&E, and reviewed by an experienced pathologist (I.I.W.). The 413 tissue specimens collected from 283 patients included 62 normal bronchial epithelia, 61 bronchial hyperplasias (Hyp), 15 squamous metaplasias (SqM), 9 squamous dysplasias (Dys), 26 carcinomas in situ (CIS), as well as 98 squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) and 141 adenocarcinomas. Normal bronchial epithelia, hyperplasia, squamous metaplasia, dysplasia, CIS, and SCC were considered to represent different steps in the development of SCCs. All tumors and lesions were classified according to the World Health Organization (WHO) 2004 criteria. The TMAs were prepared with a manual tissue arrayer (Advanced Tissue Arrayer ATA100, Chemicon International, Temecula, CA) using 1-mm-diameter cores in triplicate for tumors and 1.5 to 2-mm cores for normal epithelial and premalignant lesions. -

Proteomic Responses to Ocean Acidification in the Brain of Juvenile

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.25.115527; this version posted May 28, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Proteomic responses to ocean acidification in the brain of juvenile coral reef fish Hin Hung Tsang1, Megan Welch2, Philip L. Munday2, Timothy Ravasi3, Celia Schunter1* 1Swire Institute of Marine Science, School of Biological Sciences, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong SAR 2Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef StuDies, James Cook University, Townsville, QueenslanD, 4811, Australia 3Marine Climate Change Unit, Okinawa Institute of Science anD Technology Graduate University, 1919–1 Tancha, Onna-son, Okinawa 904–0495, Japan *correspondence to: [email protected] 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.25.115527; this version posted May 28, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Abstract Elevated CO2 levels predicted to occur by the end of the century can affect the physiology and behaviour of marine fishes. For one important survival mechanism, the response to chemical alarm cues from conspecifics, substantial among-individual variation in the extent of behavioural impairment when exposed to elevated CO2 has been observed in previous studies. -

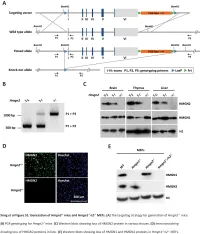

The Hmgn Family of Chromatin Binding Proteins Regulate Stem Cell Pluripotency and Neuronal Differentiation

The Hmgn family of chromatin binding proteins regulate stem cell pluripotency and neuronal differentiation Gokula Mohan, Ohoud Rehbini, Tomoko Iwata, Katherine West Institute of Cancer Sciences, University of Glasgow Hmgn proteins Hmgn proteins are enriched across Hmgn2 is expressed in neural progenitor cells the Oct4 and Nanog gene loci during embryogenesis E11.5 E13.5 E15.5 Bind as dimers to nucleosomes svz Hmgn1 Hmgn2 svz 3 Regulate the deposition of histone 3 3 2.5 modifications 2.5 2.5 2 2 2 1.5 Compete with linker histones 1.5 1.5 1 enrichment 1 1 Interact with several transcription 0.5 0.5 0.5 factors. 0 0 0 svz: ventricular/ -1781 -399 410 2070 3342 -1081 -219 929 1740 2636 Actin Msat c subventricular zone Kato H et al. PNAS 2011;108:12283-12288 Oct4 Nanog H3 dg dg: dentate gyrus (in hippocampus) control cells NLS Nucleosome-binding domain NLS Regulatory domain 2 2 2 very highly conserved Competes with H1 c: cerebellum 1.5 1.5 1.5 100 aa 1 1 1 P14 Inhibits phosphorylation Increases acetylation enrichment 0.5 0.5 0.5 of H3S10 of H3K14 0 0 0 -1781 -399 410 2070 3342 -1081 -219 929 1740 2636 Actin Msat Retinoic acid-induced differentiation of EC P Oct4 Nanog cells down the neuronal lineage. M A A P Reprogramming Differentiation Hmgn1 and Hmgn2 binding profiles in control cells. Enrichment at each PCR set was normalised to Histone H3 N-terminal tail ARTKQTARKSTGGKAPRKQLATKAARKSA... stage stage input and then normalised to average H3 enrichment across all primer sets to control for differences M between chromatin preps. -

Integrated Genomics and Therapeutics Predictors of Small

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.09.980623; this version posted April 7, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. This article is a US Government work. It is not subject to copyright under 17 USC 105 and is also made available for use under a CC0 license. 1 SCLC_CellMiner: Integrated Genomics and Therapeutics Predictors of Small Cell Lung 2 Cancer Cell Lines based on their genomic signatures 3 4 Camille Tlemsani1,†,*, Lorinc Pongor1,†, Luc Girard4, Nitin Roper1, Fathi Elloumi1, Sudhir 5 Varma1, Augustin Luna5, Vinodh N. Rajapakse1, Robin Sebastian1, Kurt W. Kohn1, Julia 6 Krushkal2, Mirit Aladjem1, Beverly A. Teicher2, Paul S. Meltzer3, William C. Reinhold1, John D. 7 Minna4, Anish Thomas1 and Yves Pommier1, 6 8 9 1 Developmental Therapeutics Branch and Laboratory of Molecular Pharmacology, Center for 10 Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA 11 12 2 Biometric Research Program, Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, National Cancer 13 Institute, NIH, 9609 Medical Center Dr., Rockville, MD 20850, USA 14 15 3 Genetics Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD 20892, 16 USA 17 18 4 Hamon Center for Therapeutic Oncology Research, UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, 19 TX 75390, USA 20 21 5 cBio Center, Division of Biostatistics, Department of Data Sciences, Dana-Farber Cancer 22 Institute, Boston, MA 02115, USA 23 24 6 To whom correspondence should be addressed: 25 [email protected] 26 27 * present address, INSERM U1016, Cochin Institute, Paris Descartes University, 75014 Paris 28 29 † Contributed equally to the study 30 31 32 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.09.980623; this version posted April 7, 2020.