The Elusive Disciple: Cross-Cultural Perceptions of Discipleship 169

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MARY MAGDALENE: a MISUNDERSTOOD BIOGRAPHY – ‘Six Men & Six Women’ Series

MARY MAGDALENE: A MISUNDERSTOOD BIOGRAPHY – ‘Six Men & Six Women’ Series You know if you are feeling tired this morning, you should really appreciate the crew who were here at 8:00 this morning. If I have ever been teaching and felt like I needed to inject an audience with something, I just witnessed it. I mean they were tired, but they were troopers for coming out and being a part of the early service. I know that you guys are excited today because it is one of those days where we will just break our New Year commitments as we begin to go off the deep end. I mean we will be eating really well today, since it is Easter, and now we are hosed. It just goes awry from here on. So I hope you have a good Easter Sunday with good fellowship. And I hope that this morning you will sense something from God’s word that you can take away from the message that will be an encouragement to you. Let me start off with a story. Several years ago, I was serving as an associate pastor in Conway, Arkansas at Celebration Church. It was a new church, and I was there on staff. I came in one Sunday morning, and I saw my bride getting a cup of coffee. So I went up behind her and began to give her a massage on her shoulders. But then she turned around, and lo and behold, it wasn’t my wife! I was horrified in that moment. What made it even worse was she was a first time guest to our church and I never saw that lady again. -

The Disciple Whom Jesus Loved

John The Disciple Whom Jesus Loved The New Testament writings associated with John the Beloved present him as both a teacher and a model for our own discipleship. By Eric D. Huntsman Professor of Ancient Scripture, Brigham Young University fter Peter, John is perhaps the best known of Jesus’s original Twelve Apostles. He and his brother, James, were with Peter at some of the most important moments of the Savior’s mortal ministry, and Ahe has been traditionally associated with five different books in the New Testament.1 His personal closeness to the Lord is suggested by John 13:23: “Now there was leaning on Jesus’ bosom one of his disciples, whom Jesus loved.” Throughout the ages, Christian art has reflected this image, pic- turing John as a young man, often resting in the Savior’s arms. This is the origin of his unique title, John the Beloved, but his witness and mission reveal aspects of discipleship that we can all share. John, Son of Zebedee John’s Hebrew name, Yohanan, means “God has been gracious.” Most of the details we know about him come from the first three Gospels, which tell the story of the Savior’s mortal ministry largely from the same per- spective. They all agree that John was the son of a prosperous Galilean CARL BLOCH BY fisherman named Zebedee, who owned his own boat and was able to hire day laborers to assist him and his sons in their work. John and his brother, James, also had a partnership with brothers Peter and Andrew, and all four THE LAST SUPPER, left their fishing business when Jesus called them to follow Him in full-time 2 discipleship. -

Palm Sunday, We’Ll Arrive at the Distinct Point of Holy Week

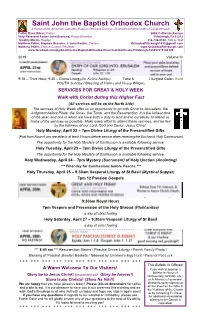

Saint John the Baptist Orthodox Church A Parish of the American Carpatho-Russian Orthodox Diocese, Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople Father Dave Urban, Pastor 2688 California Avenue Very Reverend Father John Brancho, Pastor Emeritus Pittsburgh, Pa 15212 Timothy Martin, Reader 412-748-0148, Talk or Text Matthew Peifer, Stephen Brancho, & John Radick, Cantors [email protected] Matthew Peifer, Church Council President www.OrthodoxPittsburgh.com www.facebook.com/pg/St-John-the-Baptist-Orthodox-Church-of-Northside-Pittsburgh-169297619784149 2019 Volume IV 9:15 – Third Hour; 9:30 – Divine Liturgy(for Kvitna Nedilja) Tone 6 Liturgical Color: Gold YOUTH Sunday / Blessing of Palms and Pussy Willows SERVICES FOR GREAT & HOLY WEEK Walk with Christ during this Higher Fast (All services will be on the North Side) The services of Holy Week offer us an opportunity to go with Christ to Jerusalem, the Judgment before Pilate, the Cross, the Tomb, and the Resurrection. It is the holiest time of the year, and one in which we have both a duty to God and to ourselves to attend as many of the services as possible. Make every effort to attend these services, and be fed by the holiness of our Lord, God and Savior, Jesus Christ. Holy Monday, April 22 – 7pm Divine Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts (Fast from Noon if you are able or at least 3 hours before service when receiving the Eucharist, Holy Communion) The opportunity for the Holy Mystery of Confession is available following service. Holy Tuesday, April 23 – 7pm Divine Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts The opportunity for the Holy Mystery of Confession is available following service. -

St. Gabriel the Archangel Catholic Church

May 13, 2018 The Ascension of the Lord ST. GABRIEL THE ARCHANGEL CATHOLIC CHURCH STEWARDSHIP REFLECTION ON READINGS ACTS 1: 1-11; PS 47: 2-3, 6-9; EPH 1: 17-23; MK 16: 15- 20 We often cite Jesus’ quote from today’s Gospel of Mark: “Go into the whole world and proclaim the gospel to every creature.” This was not a suggestion from the Lord. It was quite frankly a command, and it is one which still holds for each of us. Being an evangelist, being a disciple, being a steward is not a matter of choice for those of us who are Catholic and Christian. It is something the Lord expects of us. Often we may like to spend time debating how to do that, but that does not lessen the fact that it is something we are supposed to do. We need to acknowledge that even the original Apostles and followers of Jesus did not do that immediately. We learn that they stayed in Jerusalem for some time, and it seemed to be only when the Church and its followers were persecuted that they began to reach out and truly share the “Good News.” Once Christians accepted that charge from the Lord, they did indeed take the Word of God to all corners of the earth. Look at the Church today. It is incredible how this Church has grown from one Man/God and a small group into what it is today. That does not, however, get us “off the hook.” As much as we may argue about how to carry out this command from Jesus, the fact remains that our very lives need to stand as a representation of what it means to be a Christian, what it means to “love one another,” what it means to live and to work as a disciple of Christ. -

St Joseph As Dreamer and Disciple: the Gospels View by Arthur E

St Joseph as Dreamer and Disciple: The Gospels View By Arthur E. Zannoni Pre Note: On December 8, 2020, Pope Francis proclaimed in an Apostolic Letter entitled “Patris corde” (“With a Father’s Heart”) a “Year of Saint Joseph” from December 8, 2020, to December 8, 2021. Also, the Church celebrates the Solemnity (feast) of St. Joseph liturgically on March 19. Thus, the following reflection is offered on Joseph's biblical roots, the spouse of Mary, the mother of Jesus. What the Gospels Reveal About St. Joseph The only source we have for St. Joseph is the gospels. He is mentioned sixteen times in three of the four gospels. Matthew mentions him eight times, Luke seven times, and John once. This singular reference to Joseph in John's gospel (6:41-42) only refers to Joseph as the father of Jesus. The Portrayal of Joseph in the Gospel of Matthew In Matthew's gospel's infancy narrative, the first time Joseph is mentioned is in the genealogy of Jesus (Matthew 1:1-17), and he is called the husband of Mary (1:16). The second time Joseph is referred to as betrothed to Mary. They are engaged, “but before they lived together, she [Mary] was found to be with child from the Holy Spirit” (1:18). Mary and Joseph are between two stages of ancient Jewish marriage. The first is the formal consent in the home of the father of the bride. The second, made later, is the transfer of the bride to the house of the groom. In the Jewish legal view, Mary and Joseph's betrothal was considered a legally contracted marriage, completed before they cohabitated. -

What Is Discipleship?

What is Discipleship? Living the Message: Sharing Good News & Growth LifeSpring Seminar Series Presenter: Israel Steinmetz Presentation Outline Discipleship in Scripture Discipleship Definitions Key Issues in Discipleship A Proposed Definition The Challenge of Discipleship Discipleship in scripture Disciple and related terms (disciple-making, learner) are derived from the Greek mathetes. “Disciple” = Used in the Gospels (x230) and Acts (x28) to designate those who followed Jesus Christ. “Disciple-making” = Used in Matthew 28:19 Deliverance- evangelism/baptism Development- spiritual formation Deployment- reproduction This slide taken from Bill Hull, The Complete Book of Discipleship. Discipleship in scripture Learner = verbal form of mathetes, used 13 times in Paul’s letters Spiritual Formation Galatians 4:19- morphe = to shape Romans 8:29, 12:2 Discipleship = a derivative of biblical terms. This slide taken from Bill Hull, The Complete Book of Discipleship. Defining Discipleship “Discipleship means adherence to Christ…Christianity without the living Christ is inevitably Christianity without discipleship, and Christianity without discipleship is always Christianity without Christ.” Dietrich Bonhoeffer, The Cost of Discipleship Defining Discipleship “Discipleship is the relationship I stand into Jesus Christ in order that I might take on his character. As his disciple, I am learning from him how to live my life in the Kingdom as he would if he were I. The natural outcome is that my behavior is transformed. Increasingly, I routinely and easily do the things he said and did.” Dallas Willard, “Spiritual Formation Forum” Defining Discipleship “A disciple, then, is a reborn follower of Jesus…At the moment of salvation, when someone decides to follow Christ, he shouldn’t experience any interruption in his journey from that point forward. -

St. Matthew from an Accounting Perspective

Accounting Historians Notebook Volume 23 Number 2 October 2000 Article 10 October 2000 St. Matthew from an accounting perspective Andrew D. Sharp Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/aah_notebook Part of the Accounting Commons, and the Taxation Commons Recommended Citation Sharp, Andrew D. (2000) "St. Matthew from an accounting perspective," Accounting Historians Notebook: Vol. 23 : No. 2 , Article 10. Available at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/aah_notebook/vol23/iss2/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Archival Digital Accounting Collection at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Accounting Historians Notebook by an authorized editor of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sharp: St. Matthew from an accounting perspective ST MATTHEW FROM AN ACCOUNTING PERSPECTIVE by Andrew D. Sharp, Spring Hill College St. Matthew is the patron saint of sources as to when the Gospel of St. Matthew accountants, tax collectors, bankers, customs was written. officers and security guards. He was origi nally called Levi; however, this follower of The Tax Collector Jesus took the name Matthew-the gift of Eliade [1987] reports that, during St. Yahweh-when called to be a disciple. St. Matthew's time, tax collectors were viewed Matthew's feast day is celebrated on as serious sinners. Private entrepreneurs pur September 21st. chased the right from the government to col lect taxes. These aggressive businessmen The Conversion were able to generate enormous profits to the Other than what is recorded in the detriment of the public. Bible-that he was a tax collector by profes The Catholic Information Network sion-very little is known of the life of St. -

“Ministry Moment” Promoting PRUMC Disciple Bible Study Chris Gabriel, August 20, 2017

“Ministry Moment” Promoting PRUMC Disciple Bible Study Chris Gabriel, August 20, 2017 Have you ever been “bambuseled”? Perhaps not, since I just made up the word. It means the sense of abuse you feel when you have been bamboozled into buying or doing something that didn’t live up to the promises it made. Maybe you were sold a device that said it would take 10 shots off of your golf score. Maybe you tried a cream that promised to remove years of wrinkles. Maybe you were excited to enjoy a special craft product or curated experience that turned out to be just repackaged and tired old stuff. In each case, perhaps you were disappointed, hoodwinked, conned. Bambuseled. I’ve been bambuseled, so I appreciate the importance of making you a promise that I am absolutely 100% sure will be true no matter who you are. Disciple Bible study will change your life. I know, because it changed mine. Maybe you are a spiritual seeker looking for answers to all of the big questions. Why are we here? What is our purpose? The answers are in the Bible. Maybe you are a pragmatic doer trying to be effective and productive in your life. The Bible is the owner’s manual from the God who made you. Maybe you are hoping to find comfort and truth. The Bible is the Good News and reading it reveals the meaning of the Christian message. Disciple also will make you part of a marvelous community of believers young and old with a wealth of experiences and perspectives to share. -

Jesus Christ in the Life of John Gabriel Perboyre1

Jesus Christ in the Life of John Gabriel Perboyre1 by Álvaro Quevedo, C.M. Province of Colombia Introduction John Gabriel Perboyre “alter Christus,” was the image that was carved into my memory, from my years as a Vincentian seminarian. In the varied iconography of John Gabriel, there are two well-known images that relate him directly to Jesus Christ. The first is that of his death on the cross, which has a powerful impact on the persons who see it for the first time and ask why “that saint” is on the cross like Jesus Christ. The other image is that of the saint with traditional Chinese attire, holding a crucifix in his hands and gazing at it with devotion, as though rapt in profound meditation. 1. His love for Jesus Christ The biographers of John Gabriel recount that devotion to Jesus Christ was characteristic of him: his preferred readings were those that referred to Christ, and among the books of the New Testament, his favorites were the gospels and the letters of St. Paul. It was said that Our Lord was always on his lips and in his heart, and that he loved him more tenderly than a child loves his father. In all things he wished to please Jesus Christ, in his thoughts and actions, to such a degree that he became a living image of Jesus Christ. Speaking of Christ he would become enthusiastic and even eloquent. He used to say: Jesus Christ, is the great Teacher of knowledge; it is he alone who gives the true light. -

Disciplegroup

DiscipleGroup October 8, 2017- Aquila and Priscilla Disciple Apollos Open in Prayer Welcome/Introductions [If there are new people in your group, give brief introductions.] Remind the group of DiscipleGroup Guidelines DISCIPLEMAKER QUESTIONS • What has changed in your life because of what you learned last week? • Has God placed someone in your life outside this group that you need to invest in? • How do you think God wants you to do this? Ask a “hook question” to get the group going. • Share a time when the minute you met someone, you knew you would be friends. Share background for the story. Last week we looked at Paul’s extended mission work in the city of Corinth and the beginning of his relationship with Aquila and Priscilla. This week we will look at Aquila and Priscilla’s continued disciplemaking. Tell the story – Acts 18:18-28 This week’s story is about Aquila and Priscilla helping Apollos. [Tell the story with your Bible open on your lap to the passage.] Rebuild the story [Group members tell the story together, one piece at a time, based on what they remember.] Read the story out loud – Read Acts 18:18-28 from the Bible. [The scripture may have more details. Were there any important details left out of the telling or retelling that you discover in the scripture?] Discuss these questions: 1. What do you learn about God, Jesus or the Holy Spirit in this story? 2. What do you learn about the characters in the story? 3. What stood out to you in the story? 4. -

Acts of Witnessing

EPISODE 3 – ACTS OF WITNESSING HOLY SPIRIT – THE FLAME WITHIN ME SERIES (ACTS 16:16-34) • Just before Jesus was taken up into heaven, He told His disciples in Acts 1:8; “But you will receive power when the Holy Spirit comes on you. Then you will tell people about me in Jerusalem, and in all Judea and Samaria. And you will even tell other people about me from one end of the earth to the other.” • You might remember on Day 2 we learned about a man names Saul, who we now know as Paul. He was a man who persecuted the followers of Jesus. He wanted them all arrested and punished for believing that Jesus was the Son of God. • But Jesus appeared to him when he was traveling to Damascus to arrest Jesus’ followers. Jesus made him blind but healed his heart so that he could understand who Jesus really was. • In Damascus there was a disciple named Ananias. The Lord called to Ananias in a vision and told him to go to Saul. He was to place his hands on him to restore his sight. • Ananias had every reason to be afraid. He responded to the Lord, “This man has harmed your holy people in Jerusalem. And he has come here with authority from the chief priests to arrest all who call on your name.” (CONTINUED ON NEXT PAGE) 1 • But the Lord replied, “Go! I have chosen Saul to proclaim my Name not only to Jews but Gentiles and their kings. I will also show him how much he must suffer for me.” • Ananias went to the house and placed his hands on Saul. -

Disciple?” Is Every Christian a Disciple of Jesus?

Jesus says “Who is My Disciple?” Is every Christian a disciple of Jesus? True or False: the terms “Christian” and “disciple” are synonymous Is there a difference between a “believer in Jesus” and a “follower of Jesus”? entering into the Kingdom of Jesus occurs responsively in a moment living as a disciple of Jesus the King develops intentionally over time Jesus Reveals the Goal of the Disciple Luke 6:40 A disciple is not above his teacher, but everyone when he is fully trained will be like his teacher. Jesus Reveals the Goal of the Disciple Jesus Reveals the Goal of the Disciple ๏ I follow, learn from, train under & become like Jesus, such that His life is lived through me Jesus Reveals the Goal of the Disciple ๏ I follow, learn from, train under & become like Jesus, such that His life is lived through me ๏ i.e. to be transformed into Jesus-likeness and to be engaged in His mission in this world Jesus Reveals the Goal of the Disciple ๏ I follow, learn from, train under & become like Jesus, such that His life is lived through me ๏ i.e. to be transformed into Jesus-likeness and to be engaged in His mission in this world ๏ Jesus call to be His disciple requires we both consider the cost and pursue His purposes As Disciples, We Settle Three Big Issues if not, Jesus says, “you cannot be My disciple” Luke 14:26 “If anyone comes to Me and does not hate his own father and mother and wife and children and brothers and sisters, yes, and even his own life, he cannot be My disciple.” — Jesus As Disciples, We Settle Three Big Issues RELATIONSHIP if