Was Jesus Ever a Disciple of John the Baptist? a Historical Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MARY MAGDALENE: a MISUNDERSTOOD BIOGRAPHY – ‘Six Men & Six Women’ Series

MARY MAGDALENE: A MISUNDERSTOOD BIOGRAPHY – ‘Six Men & Six Women’ Series You know if you are feeling tired this morning, you should really appreciate the crew who were here at 8:00 this morning. If I have ever been teaching and felt like I needed to inject an audience with something, I just witnessed it. I mean they were tired, but they were troopers for coming out and being a part of the early service. I know that you guys are excited today because it is one of those days where we will just break our New Year commitments as we begin to go off the deep end. I mean we will be eating really well today, since it is Easter, and now we are hosed. It just goes awry from here on. So I hope you have a good Easter Sunday with good fellowship. And I hope that this morning you will sense something from God’s word that you can take away from the message that will be an encouragement to you. Let me start off with a story. Several years ago, I was serving as an associate pastor in Conway, Arkansas at Celebration Church. It was a new church, and I was there on staff. I came in one Sunday morning, and I saw my bride getting a cup of coffee. So I went up behind her and began to give her a massage on her shoulders. But then she turned around, and lo and behold, it wasn’t my wife! I was horrified in that moment. What made it even worse was she was a first time guest to our church and I never saw that lady again. -

The Disciple Whom Jesus Loved

John The Disciple Whom Jesus Loved The New Testament writings associated with John the Beloved present him as both a teacher and a model for our own discipleship. By Eric D. Huntsman Professor of Ancient Scripture, Brigham Young University fter Peter, John is perhaps the best known of Jesus’s original Twelve Apostles. He and his brother, James, were with Peter at some of the most important moments of the Savior’s mortal ministry, and Ahe has been traditionally associated with five different books in the New Testament.1 His personal closeness to the Lord is suggested by John 13:23: “Now there was leaning on Jesus’ bosom one of his disciples, whom Jesus loved.” Throughout the ages, Christian art has reflected this image, pic- turing John as a young man, often resting in the Savior’s arms. This is the origin of his unique title, John the Beloved, but his witness and mission reveal aspects of discipleship that we can all share. John, Son of Zebedee John’s Hebrew name, Yohanan, means “God has been gracious.” Most of the details we know about him come from the first three Gospels, which tell the story of the Savior’s mortal ministry largely from the same per- spective. They all agree that John was the son of a prosperous Galilean CARL BLOCH BY fisherman named Zebedee, who owned his own boat and was able to hire day laborers to assist him and his sons in their work. John and his brother, James, also had a partnership with brothers Peter and Andrew, and all four THE LAST SUPPER, left their fishing business when Jesus called them to follow Him in full-time 2 discipleship. -

The Imprisonment of Jeremiah in Its Historical Context

The Imprisonment of Jeremiah in Its Historical Context kevin l. tolley Kevin L. Tolley ([email protected]) is the coordinator of Seminaries and Institutes of Religion in Fullerton, California. he book of Jeremiah describes the turbulent times in Jerusalem prior to Tthe Babylonian conquest of the city. Warring political factions bickered within the city while a looming enemy rapidly approached. Amid this com- . (wikicommons). plex political arena, Jeremiah arose as a divine spokesman. His preaching became extremely polarizing. These political factions could be categorized along a spectrum of support and hatred toward the prophet. Jeremiah’s imprisonment (Jeremiah 38) illustrates some of the various attitudes toward God’s emissary. This scene also demonstrates the political climate and spiritual atmosphere of Jerusalem at the verge of its collapse into the Babylonian exile and also gives insights into the beginning narrative of the Book of Mormon. Jeremiah Lamenting the Destruction of Jerusalem Jeremiah Setting the Stage: Political Background for Jeremiah’s Imprisonment In the decades before the Babylonian exile in 587/586 BC, Jerusalem was the center of political and spiritual turmoil. True freedom and independence had Rembrandt Harmensz, Rembrandt not been enjoyed there for centuries.1 Subtle political factions maneuvered The narrative of the imprisonment of Jeremiah gives us helpful insights within the capital city and manipulated the king. Because these political into the world of the Book of Mormon and the world of Lehi and his sons. RE · VOL. 20 NO. 3 · 2019 · 97–11397 98 Religious Educator ·VOL.20NO.3·2019 The Imprisonment of Jeremiah in Its Historical Context 99 groups had a dramatic influence on the throne, they were instrumental in and closed all local shrines, centralizing the worship of Jehovah to the temple setting the political and spiritual stage of Jerusalem. -

Christian Origins Seminar Spring Meeting 2010

Spring Meeting 2010 Ballot 1 Story and Ritual as the Foundation of Nations Helmut Koester Report from the Jesus Seminar Q1 Story and ritual are the religio-political foundations of the on Christian Origins founding of nations in Antiquity. This is demonstrated in brief survey of the founding of the nations of the Hellenes, of Israel, and of imperial Rome. Fellows 0.88 Red 0.75 %R 0.20 %P 0.00 %G 0.05 %B Associates 0.86 Red 0.68 %R 0.27 %P 0.00 %G 0.05 %B Q2 The beginnings of the early Christian movement are Stephen J. Patterson, Chair political rather than “religious”; Paul wants to create a new nation of justice and equality opposed to the unjust hierarchical establishment of imperial Rome. This is dis- cussed with reference to John the Baptist, Jesus and Paul. Fellows 0.58 Pink 0.15 %R 0.55 %P 0.20 %G 0.10 %B Associates 0.61 Pink 0.18 %R 0.45 %P 0.36 %G 0.00 %B The Jesus Seminar on Christian Origins convened on Q3 As early Christians churches tried to find their place as a March 19–20 to consider some remaining issues associ- “religion” in the Greco-Roman world they soon began to become conform with the morality and citizenship of the ated with Antioch, and to air out some long-standing ques- Roman society. tions associated with the work of the Jesus Seminar. It was a Fellows 0.78 Red 0.50 %R 0.35 %P 0.15 %G 0.00 %B remarkable meeting. -

Palm Sunday, We’Ll Arrive at the Distinct Point of Holy Week

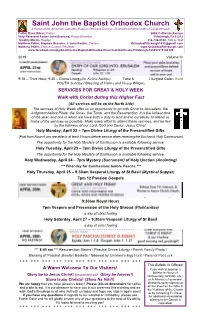

Saint John the Baptist Orthodox Church A Parish of the American Carpatho-Russian Orthodox Diocese, Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople Father Dave Urban, Pastor 2688 California Avenue Very Reverend Father John Brancho, Pastor Emeritus Pittsburgh, Pa 15212 Timothy Martin, Reader 412-748-0148, Talk or Text Matthew Peifer, Stephen Brancho, & John Radick, Cantors [email protected] Matthew Peifer, Church Council President www.OrthodoxPittsburgh.com www.facebook.com/pg/St-John-the-Baptist-Orthodox-Church-of-Northside-Pittsburgh-169297619784149 2019 Volume IV 9:15 – Third Hour; 9:30 – Divine Liturgy(for Kvitna Nedilja) Tone 6 Liturgical Color: Gold YOUTH Sunday / Blessing of Palms and Pussy Willows SERVICES FOR GREAT & HOLY WEEK Walk with Christ during this Higher Fast (All services will be on the North Side) The services of Holy Week offer us an opportunity to go with Christ to Jerusalem, the Judgment before Pilate, the Cross, the Tomb, and the Resurrection. It is the holiest time of the year, and one in which we have both a duty to God and to ourselves to attend as many of the services as possible. Make every effort to attend these services, and be fed by the holiness of our Lord, God and Savior, Jesus Christ. Holy Monday, April 22 – 7pm Divine Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts (Fast from Noon if you are able or at least 3 hours before service when receiving the Eucharist, Holy Communion) The opportunity for the Holy Mystery of Confession is available following service. Holy Tuesday, April 23 – 7pm Divine Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts The opportunity for the Holy Mystery of Confession is available following service. -

On Putting Paul in His Place Author(S): Victor Paul Furnish Reviewed Work(S): Source: Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol

On Putting Paul in His Place Author(s): Victor Paul Furnish Reviewed work(s): Source: Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol. 113, No. 1 (Spring, 1994), pp. 3-17 Published by: The Society of Biblical Literature Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3266307 . Accessed: 06/04/2012 10:44 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Society of Biblical Literature is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Biblical Literature. http://www.jstor.org JBL 113/1(1994) 3-17 ON PUTTING PAUL IN HIS PLACE* VICTOR PAUL FURNISH Perkins School of Theology, Southern Methodist University, Dallas, TX 75275 Paul is easily the most accessible figure in first-century Christianity, arguably the most important; and, of course, he has been the subject of countless scholarly studies. Yet he remains, in many respects, an enigmatic figure. He seems to have been a puzzle even to his contemporaries, perhaps no less to many of his fellow believers in the church than to most of his former colleagues in the synagogue. And over time, also his letters became a problem, as attested by that oft-quoted remark in 2 Peter, "there are some things in them hard to understand" (3:16). -

St. Gabriel the Archangel Catholic Church

May 13, 2018 The Ascension of the Lord ST. GABRIEL THE ARCHANGEL CATHOLIC CHURCH STEWARDSHIP REFLECTION ON READINGS ACTS 1: 1-11; PS 47: 2-3, 6-9; EPH 1: 17-23; MK 16: 15- 20 We often cite Jesus’ quote from today’s Gospel of Mark: “Go into the whole world and proclaim the gospel to every creature.” This was not a suggestion from the Lord. It was quite frankly a command, and it is one which still holds for each of us. Being an evangelist, being a disciple, being a steward is not a matter of choice for those of us who are Catholic and Christian. It is something the Lord expects of us. Often we may like to spend time debating how to do that, but that does not lessen the fact that it is something we are supposed to do. We need to acknowledge that even the original Apostles and followers of Jesus did not do that immediately. We learn that they stayed in Jerusalem for some time, and it seemed to be only when the Church and its followers were persecuted that they began to reach out and truly share the “Good News.” Once Christians accepted that charge from the Lord, they did indeed take the Word of God to all corners of the earth. Look at the Church today. It is incredible how this Church has grown from one Man/God and a small group into what it is today. That does not, however, get us “off the hook.” As much as we may argue about how to carry out this command from Jesus, the fact remains that our very lives need to stand as a representation of what it means to be a Christian, what it means to “love one another,” what it means to live and to work as a disciple of Christ. -

A Brief Chronology

A Brief Chronology B.C.E. is an abbreviation of "Before the Common Era" and C.E. of the "Common Era." The Common Era is that of the Gregorian calendar, where time is measured before or after what was thought to be the birth year of Jesus: in Latin, Anno Domini, the "Year of the Lord," abbreviated A.D. In fact, Jesus' date of birth is now placed in or about 4 B.C.E. Muslims also use a "before" and "after" system. In their case the watershed date is that of the Hijrah or Emigration of Muhammad from Mecca to Medina in 622 C.E., called in the West A.H., or Anno Hegirae. Jewish time reckoning is only "after," that is, from the Creation of the World, normally understood to be about 4000 years B.C.E. B.C.E. ca. 1700 God's Covenant with Abraham ca. 1200 The exodus from Egypt; the giving of the Torah to Moses on Mount Sinai ca. 1000 David, king of the Israelites, captures Jerusalem and makes it his capital ca. 970 Solomon builds the First Temple in Jerusalem 621 Josiah centralizes all Jewish worship in the Temple in Jeru- salem 587 Babylonians under Nebuchadnezzar carry Israelites into exile in Babylon; the destruction of Solomon's Temple £38 Exiles return to Judea; Ezra; Nehemiah; rebuilding of Jerusa- lem Temple 332 Alexander the Great in the Near East; Greek dynasties rule Palestine ca. 280 Translation of Bible in Greek: the "Septuagint" 200 The Seleucid dynasty of Syria replaces the Ptolemies as rulers of Palestine 17 £-164 Antiochus IV Epiphanes; profanation of the Temple 164 Maccabean revolt; Jewish independence 164-37 The Hasmonean dynasty rules Palestine xviii CHRONOLOGY 37-4 Herod the Great, king of Judea ca. -

St Joseph As Dreamer and Disciple: the Gospels View by Arthur E

St Joseph as Dreamer and Disciple: The Gospels View By Arthur E. Zannoni Pre Note: On December 8, 2020, Pope Francis proclaimed in an Apostolic Letter entitled “Patris corde” (“With a Father’s Heart”) a “Year of Saint Joseph” from December 8, 2020, to December 8, 2021. Also, the Church celebrates the Solemnity (feast) of St. Joseph liturgically on March 19. Thus, the following reflection is offered on Joseph's biblical roots, the spouse of Mary, the mother of Jesus. What the Gospels Reveal About St. Joseph The only source we have for St. Joseph is the gospels. He is mentioned sixteen times in three of the four gospels. Matthew mentions him eight times, Luke seven times, and John once. This singular reference to Joseph in John's gospel (6:41-42) only refers to Joseph as the father of Jesus. The Portrayal of Joseph in the Gospel of Matthew In Matthew's gospel's infancy narrative, the first time Joseph is mentioned is in the genealogy of Jesus (Matthew 1:1-17), and he is called the husband of Mary (1:16). The second time Joseph is referred to as betrothed to Mary. They are engaged, “but before they lived together, she [Mary] was found to be with child from the Holy Spirit” (1:18). Mary and Joseph are between two stages of ancient Jewish marriage. The first is the formal consent in the home of the father of the bride. The second, made later, is the transfer of the bride to the house of the groom. In the Jewish legal view, Mary and Joseph's betrothal was considered a legally contracted marriage, completed before they cohabitated. -

Miranda Threlfall-Holmes Is Vicar of Belmont and Pittington in the Diocese of Durham, and an Honorary Fellow of Durham University

Miranda Threlfall-Holmes is Vicar of Belmont and Pittington in the Diocese of Durham, and an honorary fellow of Durham University. Previously, she was Chaplain and Solway Fellow of University College, Durham, and a member of the Church of England General Synod. She has first-class degrees in both history (from Cambridge) and theology (from Durham), and a PhD in medieval history. She trained for ordination at Cranmer Hall, Durham, and was then a curate at St Gabriel’s church in Heaton, Newcastle upon Tyne. She has taught history at Durham and Newcastle universities, as well as for the North East Institute for Theological Education, the Lindisfarne Regional Training Partnership and Cranmer Hall. As a historian and theologian, she has written and published extensively in both the aca- demic and popular media. Her doctoral thesis, Monks and Markets: Durham Cathedral Priory 1460–1520, was published by Oxford University Press in 2005, and she co-edited Being a Chaplain with Mark Newitt in 2011 (published by SPCK). She has also contributed to the Church Times, The Guardian and Reuters. THE essential historY OF christianitY MIRANDA THRELFALL-HOLMES First published in Great Britain in 2012 Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge 36 Causton Street London SW1P 4ST www.spckpublishing.co.uk Copyright © Miranda Threlfall-Holmes 2012 Miranda Threlfall-Holmes has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. -

(In Spirit): Wealth and Poverty in the Writings of the Greek Christian Fathers of the Second Century

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 8-2021 Blessed Are the Poor (in Spirit): Wealth and Poverty in the Writings of the Greek Christian Fathers of the Second Century Jacob D. Hayden Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons Recommended Citation Hayden, Jacob D., "Blessed Are the Poor (in Spirit): Wealth and Poverty in the Writings of the Greek Christian Fathers of the Second Century" (2021). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 8181. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/8181 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BLESSED ARE THE POOR (IN SPIRIT): WEALTH AND POVERTY IN THE WRITINGS OF THE GREEK CHRISTIAN FATHERS OF THE SECOND CENTURY by Jacob D. Hayden A thesis submitted in partiaL fuLfiLLment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Ancient Languages and CuLtures Approved: _______________________ _____________________ Mark Damen, Ph.D. Norman Jones, Ph.D. Major Professor Committee Member _______________________ ______________________ Eliza Rosenberg, Ph.D. Patrick Q. Mason, Ph.D. Committee Member Committee Member ________________________________ D. Richard CutLer, Ph.D. Interim Vice Provost of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2021 ii Copyright © Jacob D. Hayden 2021 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Blessed Are the Poor (in Spirit): Wealthy and Poverty in the Writings of the Greek Christian Fathers of the Second Century by Jacob D. -

1 the GOSPELS Mark Written Between 65-75 CE, in Rome Matthew

1 THE GOSPELS Mark written between 65-75 CE, in Rome Matthew -- in 85, in Antioch Luke (and Acts) -- in 83-90, in Caesarea Maritime John -- ç 100 (?), in Ephesus SOURCES Q When Mark's passages are deleted from Matthew and Luke, some 200 verses remain that are strikingly similar. These are assumed to be from a common source, called Q (from the German quelle, "source.") M Material peculiar to Mark. L Material peculiar to Luke Then when the L source is compared to John, there seems to be more than coincidental affinity, indicating still another source known to both Luke and John. Paul's first letter -- 1 Thessalonians, c 48-49. Last letter -- Colossians, c 62. Paul probably died in 67 (according to Eusebius), so none of the Gospels had been written down at the time of his death. Wm Newell: In Matthew he walks before us as the King of Israel; in Mark as the Servant of Jehovah; in Luke as the Son of Man; in John as the Eternal Word, "the only begotten Son," Creator-God. GOSPEL -- from the Anglo-Saxon "godspell," meaning "good news." Bethesda – House of Grace Bethel – House of God Bethlehem – House of Bread Bethsaida – House of Fishing Eden – delight The parables. Giza Vermes: Only one of the 40 parables foreshadows the cross (wicked tenants in the vineyard (Matt 21:33 et al). That and all other allusions to the role of the Son of Man’s delayed return are later additions to the original central message of Jesus. OT quotes in the gospels: There are 41 quotes from the OT attributed to Jesus in all three synoptic gospels.