Mary Magdalene and the Disciple Jesus Loved1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lamb of God" Title in John's Gospel: Background, Exegesis, and Major Themes Christiane Shaker [email protected]

Seton Hall University eRepository @ Seton Hall Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses (ETDs) Fall 12-2016 The "Lamb of God" Title in John's Gospel: Background, Exegesis, and Major Themes Christiane Shaker [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.shu.edu/dissertations Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Shaker, Christiane, "The "Lamb of God" Title in John's Gospel: Background, Exegesis, and Major Themes" (2016). Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses (ETDs). 2220. https://scholarship.shu.edu/dissertations/2220 Seton Hall University THE “LAMB OF GOD” TITLE IN JOHN’S GOSPEL: BACKGROUND, EXEGESIS, AND MAJOR THEMES A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THEOLOGY CONCENTRATION IN BIBLICAL THEOLOGY BY CHRISTIANE SHAKER South Orange, New Jersey October 2016 ©2016 Christiane Shaker Abstract This study focuses on the testimony of John the Baptist—“Behold, the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world!” [ἴδε ὁ ἀµνὸς τοῦ θεοῦ ὁ αἴρων τὴν ἁµαρτίαν τοῦ κόσµου] (John 1:29, 36)—and its impact on the narrative of the Fourth Gospel. The goal is to provide a deeper understanding of this rich image and its influence on the Gospel. In an attempt to do so, three areas of concentration are explored. First, the most common and accepted views of the background of the “Lamb of God” title in first century Judaism and Christianity are reviewed. -

MARY MAGDALENE: a MISUNDERSTOOD BIOGRAPHY – ‘Six Men & Six Women’ Series

MARY MAGDALENE: A MISUNDERSTOOD BIOGRAPHY – ‘Six Men & Six Women’ Series You know if you are feeling tired this morning, you should really appreciate the crew who were here at 8:00 this morning. If I have ever been teaching and felt like I needed to inject an audience with something, I just witnessed it. I mean they were tired, but they were troopers for coming out and being a part of the early service. I know that you guys are excited today because it is one of those days where we will just break our New Year commitments as we begin to go off the deep end. I mean we will be eating really well today, since it is Easter, and now we are hosed. It just goes awry from here on. So I hope you have a good Easter Sunday with good fellowship. And I hope that this morning you will sense something from God’s word that you can take away from the message that will be an encouragement to you. Let me start off with a story. Several years ago, I was serving as an associate pastor in Conway, Arkansas at Celebration Church. It was a new church, and I was there on staff. I came in one Sunday morning, and I saw my bride getting a cup of coffee. So I went up behind her and began to give her a massage on her shoulders. But then she turned around, and lo and behold, it wasn’t my wife! I was horrified in that moment. What made it even worse was she was a first time guest to our church and I never saw that lady again. -

The Disciple Whom Jesus Loved

John The Disciple Whom Jesus Loved The New Testament writings associated with John the Beloved present him as both a teacher and a model for our own discipleship. By Eric D. Huntsman Professor of Ancient Scripture, Brigham Young University fter Peter, John is perhaps the best known of Jesus’s original Twelve Apostles. He and his brother, James, were with Peter at some of the most important moments of the Savior’s mortal ministry, and Ahe has been traditionally associated with five different books in the New Testament.1 His personal closeness to the Lord is suggested by John 13:23: “Now there was leaning on Jesus’ bosom one of his disciples, whom Jesus loved.” Throughout the ages, Christian art has reflected this image, pic- turing John as a young man, often resting in the Savior’s arms. This is the origin of his unique title, John the Beloved, but his witness and mission reveal aspects of discipleship that we can all share. John, Son of Zebedee John’s Hebrew name, Yohanan, means “God has been gracious.” Most of the details we know about him come from the first three Gospels, which tell the story of the Savior’s mortal ministry largely from the same per- spective. They all agree that John was the son of a prosperous Galilean CARL BLOCH BY fisherman named Zebedee, who owned his own boat and was able to hire day laborers to assist him and his sons in their work. John and his brother, James, also had a partnership with brothers Peter and Andrew, and all four THE LAST SUPPER, left their fishing business when Jesus called them to follow Him in full-time 2 discipleship. -

Palm Sunday, We’Ll Arrive at the Distinct Point of Holy Week

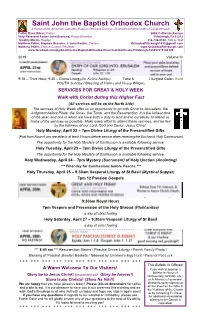

Saint John the Baptist Orthodox Church A Parish of the American Carpatho-Russian Orthodox Diocese, Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople Father Dave Urban, Pastor 2688 California Avenue Very Reverend Father John Brancho, Pastor Emeritus Pittsburgh, Pa 15212 Timothy Martin, Reader 412-748-0148, Talk or Text Matthew Peifer, Stephen Brancho, & John Radick, Cantors [email protected] Matthew Peifer, Church Council President www.OrthodoxPittsburgh.com www.facebook.com/pg/St-John-the-Baptist-Orthodox-Church-of-Northside-Pittsburgh-169297619784149 2019 Volume IV 9:15 – Third Hour; 9:30 – Divine Liturgy(for Kvitna Nedilja) Tone 6 Liturgical Color: Gold YOUTH Sunday / Blessing of Palms and Pussy Willows SERVICES FOR GREAT & HOLY WEEK Walk with Christ during this Higher Fast (All services will be on the North Side) The services of Holy Week offer us an opportunity to go with Christ to Jerusalem, the Judgment before Pilate, the Cross, the Tomb, and the Resurrection. It is the holiest time of the year, and one in which we have both a duty to God and to ourselves to attend as many of the services as possible. Make every effort to attend these services, and be fed by the holiness of our Lord, God and Savior, Jesus Christ. Holy Monday, April 22 – 7pm Divine Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts (Fast from Noon if you are able or at least 3 hours before service when receiving the Eucharist, Holy Communion) The opportunity for the Holy Mystery of Confession is available following service. Holy Tuesday, April 23 – 7pm Divine Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts The opportunity for the Holy Mystery of Confession is available following service. -

St. Gabriel the Archangel Catholic Church

May 13, 2018 The Ascension of the Lord ST. GABRIEL THE ARCHANGEL CATHOLIC CHURCH STEWARDSHIP REFLECTION ON READINGS ACTS 1: 1-11; PS 47: 2-3, 6-9; EPH 1: 17-23; MK 16: 15- 20 We often cite Jesus’ quote from today’s Gospel of Mark: “Go into the whole world and proclaim the gospel to every creature.” This was not a suggestion from the Lord. It was quite frankly a command, and it is one which still holds for each of us. Being an evangelist, being a disciple, being a steward is not a matter of choice for those of us who are Catholic and Christian. It is something the Lord expects of us. Often we may like to spend time debating how to do that, but that does not lessen the fact that it is something we are supposed to do. We need to acknowledge that even the original Apostles and followers of Jesus did not do that immediately. We learn that they stayed in Jerusalem for some time, and it seemed to be only when the Church and its followers were persecuted that they began to reach out and truly share the “Good News.” Once Christians accepted that charge from the Lord, they did indeed take the Word of God to all corners of the earth. Look at the Church today. It is incredible how this Church has grown from one Man/God and a small group into what it is today. That does not, however, get us “off the hook.” As much as we may argue about how to carry out this command from Jesus, the fact remains that our very lives need to stand as a representation of what it means to be a Christian, what it means to “love one another,” what it means to live and to work as a disciple of Christ. -

Discipleship in the Lectionary – 05/02/2021

Discipleship in the Lectionary – 05/02/2021 A look at the week's lectionary through the lens of discipleship and disciple- making. Fifth Sunday of Easter Revised Common Lectionary Year B Sunday, May 2nd John 15:1-8 Scripture quotations are from The ESV® Bible (The Holy Bible, English Standard Version®), copyright © 2001 by Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Abiding in the True Vine? Like last week’s imagery of the shepherd, the Gospel lectionary for the Fifth Sunday of Easter continues with further Old Testament imagery of Israel – the vine. There are six references to “bearing fruit” in these eight verses. The fruitfulness of a branch is associated with abiding in the vine (menō – continue, stay [remain], endure [persist]) with “abide” appearing seven times. At a time when local churches can resemble private country clubs at one end of the spectrum and political action organizations at the other, it is perhaps not surprising there is a distinct lack of fruitfulness of many church denominations across the West. The remedy – abide in the True Vine. John 15:1-8 Commentary As context, this passage is part of Jesus’ farewell discourse with His disciples (14-17) which thus gives a degree of urgency to the content. This text is also part of a larger unit with the second half appearing in next week’s lectionary (15:9-17). 1 “I am the true vine, and my Father is the vinedresser. This is the last of the seven main “I am” (ego eimi) statements of Jesus that reveal Jesus' true identity. -

WORSHIP PROGRAM December, January, February 2020-2021

WORSHIP PROGRAM December, January, February 2020-2021 MUSICAL PRELUDE December: “A Charge to Keep I Have,” AME Zion Bicentennial Hymnal, #43, or “Yes Lord Yes,” Shirley Caesar, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=InsPzsJRmLE January: “’Go Preach the Gospel,’ Saith the Lord,” AME Zion Bicentennial Hymnal, #360, or “Jesus Is Mine,” John P. Kee, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fWfH- VWTwfcY February: “Give of Your Best to the Master,” AME Zion Bicentennial Hymnal, #672, or “God in Me,” Mary Mary, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=agxi8cei9h8 CALL TO WORSHIP December: Led by an adult (1st Sunday); a young adult (2nd Sunday); a youth (3rd Sunday); and a child (4th Sunday). Leader: “Now the Lord said to Abram, ‘Go from your country and your kindred and your father’s house to the land that I will show you.” (Genesis 12:1 NRSV) All: “I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you, and make your name great, so that you will be a blessing.” (Genesis 12:2 NRSV) January: Led by a Local Preacher or Conference Evangelist (1st Sunday); a new member (2nd Sunday); a member of the intercessory prayer or prayer ministry (3rd Sun- day); and a member of a health ministry within the local church (4th Sunday). 1 Leader: “Then Jesus summoned his twelve disciples and gave them authority over unclean spirits, to cast them out, and to cure every disease and every sickness.” (Matthew 10:1 NRSV) All: “These twelve Jesus sent out with the following instructions . ‘As you go, proclaim the good news . -

St Joseph As Dreamer and Disciple: the Gospels View by Arthur E

St Joseph as Dreamer and Disciple: The Gospels View By Arthur E. Zannoni Pre Note: On December 8, 2020, Pope Francis proclaimed in an Apostolic Letter entitled “Patris corde” (“With a Father’s Heart”) a “Year of Saint Joseph” from December 8, 2020, to December 8, 2021. Also, the Church celebrates the Solemnity (feast) of St. Joseph liturgically on March 19. Thus, the following reflection is offered on Joseph's biblical roots, the spouse of Mary, the mother of Jesus. What the Gospels Reveal About St. Joseph The only source we have for St. Joseph is the gospels. He is mentioned sixteen times in three of the four gospels. Matthew mentions him eight times, Luke seven times, and John once. This singular reference to Joseph in John's gospel (6:41-42) only refers to Joseph as the father of Jesus. The Portrayal of Joseph in the Gospel of Matthew In Matthew's gospel's infancy narrative, the first time Joseph is mentioned is in the genealogy of Jesus (Matthew 1:1-17), and he is called the husband of Mary (1:16). The second time Joseph is referred to as betrothed to Mary. They are engaged, “but before they lived together, she [Mary] was found to be with child from the Holy Spirit” (1:18). Mary and Joseph are between two stages of ancient Jewish marriage. The first is the formal consent in the home of the father of the bride. The second, made later, is the transfer of the bride to the house of the groom. In the Jewish legal view, Mary and Joseph's betrothal was considered a legally contracted marriage, completed before they cohabitated. -

What Is Discipleship?

What is Discipleship? Living the Message: Sharing Good News & Growth LifeSpring Seminar Series Presenter: Israel Steinmetz Presentation Outline Discipleship in Scripture Discipleship Definitions Key Issues in Discipleship A Proposed Definition The Challenge of Discipleship Discipleship in scripture Disciple and related terms (disciple-making, learner) are derived from the Greek mathetes. “Disciple” = Used in the Gospels (x230) and Acts (x28) to designate those who followed Jesus Christ. “Disciple-making” = Used in Matthew 28:19 Deliverance- evangelism/baptism Development- spiritual formation Deployment- reproduction This slide taken from Bill Hull, The Complete Book of Discipleship. Discipleship in scripture Learner = verbal form of mathetes, used 13 times in Paul’s letters Spiritual Formation Galatians 4:19- morphe = to shape Romans 8:29, 12:2 Discipleship = a derivative of biblical terms. This slide taken from Bill Hull, The Complete Book of Discipleship. Defining Discipleship “Discipleship means adherence to Christ…Christianity without the living Christ is inevitably Christianity without discipleship, and Christianity without discipleship is always Christianity without Christ.” Dietrich Bonhoeffer, The Cost of Discipleship Defining Discipleship “Discipleship is the relationship I stand into Jesus Christ in order that I might take on his character. As his disciple, I am learning from him how to live my life in the Kingdom as he would if he were I. The natural outcome is that my behavior is transformed. Increasingly, I routinely and easily do the things he said and did.” Dallas Willard, “Spiritual Formation Forum” Defining Discipleship “A disciple, then, is a reborn follower of Jesus…At the moment of salvation, when someone decides to follow Christ, he shouldn’t experience any interruption in his journey from that point forward. -

May 17, 2020 6Th Sunday of Easter

Bulletin 000868 05-17-20 St. Mary of the Annunciation, Mundelein 150 copies MAY 17, 2020 6TH SUNDAY OF EASTER Scripture Insights Today we hear that all who believed in Jesus— Jews, Gentiles, and Samaritans alike—were sus- tained by the presence of the Holy Spirit in their Act of Spiritual Communion midst. In the Gospel reading, which continues Jesus’ My Jesus, Vision: farewell discourse from last Sunday, Jesus tells the I believe that You are present disciples about “another Paraclete” (often translat- in the Most Holy Sacrament. That ed as “Advocate,” “Counselor,” or “Comforter”). In all generations John’s Gospel account, Jesus was the first Advo- I love You above all things, cate, sent from the Father in heaven. Jesus now at St. Mary and I desire to receive You into my soul. reveals the second Advocate to his disciples as he and in the prepares them for his suffering and death, Resur- Since I cannot at this moment rection, and Ascension. The Paraclete os “the Spir- surrounding receive You sacramentally, it of truth” (John 14:17, the “Holy Spirit” (14:26), come at least spiritually into my heart. community who represents the continuing presence of Jesus I embrace You encounter Jesus on earth among his disciples. Jesus assures the as if You were already there and live as disciples,” I will not leave you orphans,” a promise fulfilled when Jesus ascends into heaven and the and unite myself wholly to You. His disciples. Holy Spirit descends onto the community of believ- Never permit me to be separated from You. -

St. Matthew from an Accounting Perspective

Accounting Historians Notebook Volume 23 Number 2 October 2000 Article 10 October 2000 St. Matthew from an accounting perspective Andrew D. Sharp Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/aah_notebook Part of the Accounting Commons, and the Taxation Commons Recommended Citation Sharp, Andrew D. (2000) "St. Matthew from an accounting perspective," Accounting Historians Notebook: Vol. 23 : No. 2 , Article 10. Available at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/aah_notebook/vol23/iss2/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Archival Digital Accounting Collection at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Accounting Historians Notebook by an authorized editor of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sharp: St. Matthew from an accounting perspective ST MATTHEW FROM AN ACCOUNTING PERSPECTIVE by Andrew D. Sharp, Spring Hill College St. Matthew is the patron saint of sources as to when the Gospel of St. Matthew accountants, tax collectors, bankers, customs was written. officers and security guards. He was origi nally called Levi; however, this follower of The Tax Collector Jesus took the name Matthew-the gift of Eliade [1987] reports that, during St. Yahweh-when called to be a disciple. St. Matthew's time, tax collectors were viewed Matthew's feast day is celebrated on as serious sinners. Private entrepreneurs pur September 21st. chased the right from the government to col lect taxes. These aggressive businessmen The Conversion were able to generate enormous profits to the Other than what is recorded in the detriment of the public. Bible-that he was a tax collector by profes The Catholic Information Network sion-very little is known of the life of St. -

The Identical-Nature of the Prologue and Farewell Discourse In

International Journal of Academic Multidisciplinary Research (IJAMR) ISSN: 2643-9670 Vol. 4, Issue 3, March – 2020, Pages: 65-75 The Identical-Nature of the Prologue and Farewell Discourse in Johannine Gospel: A Theological Quest Kolawole Oladotun Paul Department of Biblical Studies and Theology, ECWA Theological College, Kpada [email protected] Abstract: Generally, the Person of Jesus Christ and His ministry on earth is the hub of the Gospels. The Gospel of John as one of the Gospels presents account about the life and ministry of Jesus Christ. Over the years, the Gospels have been seriously scrutinized by modern scholars with the aim of ascertaining the genuineness and reliability of the record. In the same vein, the Gospel of John has attracted the attention of several readers and scholars due to its observed distinct and unique mode of presentation. However, the focus of scholars has always being on the prologue, sometimes neglecting the farewell discourse. Here, this study seeks to critically analyze and explore the prologue alongside the farewell discourse with the aim of discovering and ascertaining their identical nature. Keywords: ιόγνο, Farewell discourse, Gospel, Holy Spirit, John, Jesus Christ, Prologue. INTRODUCTION The Gospel of John is one of the accounts of Jesus life and ministry (Ramsey, 1989: 17); nevertheless, there have been growing perceptions that the Gospel writers were strongly influenced by the literary models and conventions of their day (Burridge, 1992). Although, the twenty-seven (27) books of the New Testament were accepted as canonical by the 4th century (Erickson, 1998: 86); controversy on several biblical texts began as far back as the days of the canonization (Lee Martin, 1988: 34), meanwhile, this does not in any way exclude the Gospel of John.