Training Everyday Missionaries and Disciple-Making Disciples with Irvine Presbyterian Church

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MARY MAGDALENE: a MISUNDERSTOOD BIOGRAPHY – ‘Six Men & Six Women’ Series

MARY MAGDALENE: A MISUNDERSTOOD BIOGRAPHY – ‘Six Men & Six Women’ Series You know if you are feeling tired this morning, you should really appreciate the crew who were here at 8:00 this morning. If I have ever been teaching and felt like I needed to inject an audience with something, I just witnessed it. I mean they were tired, but they were troopers for coming out and being a part of the early service. I know that you guys are excited today because it is one of those days where we will just break our New Year commitments as we begin to go off the deep end. I mean we will be eating really well today, since it is Easter, and now we are hosed. It just goes awry from here on. So I hope you have a good Easter Sunday with good fellowship. And I hope that this morning you will sense something from God’s word that you can take away from the message that will be an encouragement to you. Let me start off with a story. Several years ago, I was serving as an associate pastor in Conway, Arkansas at Celebration Church. It was a new church, and I was there on staff. I came in one Sunday morning, and I saw my bride getting a cup of coffee. So I went up behind her and began to give her a massage on her shoulders. But then she turned around, and lo and behold, it wasn’t my wife! I was horrified in that moment. What made it even worse was she was a first time guest to our church and I never saw that lady again. -

Capitol Ministries, the Bible and Leadership--Faithfulness by Ralph

M E M B E R S BIBLE STUDY U.S. CAPITOL FAITHFULNESS IN OUR JOINT MISSION TO OTHER CAPITOLS TO: LEGISLATORS FROM: PASTOR RALPH DROLLINGER 661-803-7970 24/7/365 DATE: JUNE 26, 2012 his past week I distributed to you a map of the United States that provided an update on our T common mission: To plant 50 ministries in 50 state capitols. I have been encouraged by your enthusiasm, cooperation and help in achieving this strategic objective. Thank you! Why are we doing this? How do we facilitate more men and women in public office who are mature in Christ—governing authorities who not only have the courage to fight the right battles but the strength, faithfulness, and perseverance to go the distance? By maturing them in Christ: Jesus said, “Sanctify them in truth; Thy Word is truth.” It follows that we need strong Bible teachers, evangelists and disciplemakers at every level in the career path of public servants. Thank you for faithfully opening doors in and to your state capitols! Your partnership is so helpful and effective! Paul too had such good friends. One was Tychicus. Paul trusted him with the most important of tasks: To personally deliver some of Paul’s original letters—the original autographa of Scripture—over hundreds of miles of perilous journey! How come? Like you, he was reliable and trustworthy in his partnership. Let’s drill down on this character quality this week. WEEKLY MEMBERS BIBLE STUDY IMMEDIATELY FOLLOWING FIRST-VOTES-BACK Capitol Room H324 • Dinner served, Spouses welcome I. -

Tychicus Will Tell You All About My Activities. He Is a Beloved Brother and Faithful Minister and Fellow Servant in the Lord” (Colossians 4:7)

“Tychicus will tell you all about my activities. He is a beloved brother and faithful minister and fellow servant in the Lord” (Colossians 4:7). It was common for letter writers in the first-century Greco-Roman world to As believers in the gospel of Jesus include several greetings from the author and his companions in the closing Christ, we must always speak the lines of their epistles. This was true also when the apostles sent their truth, but we must always speak it correspondence, and in today’s passage, Paul begins to draw his epistle to the Colossians to a close with remarks about two of his brothers-in-the-Lord, in love (Ephesians 4:15). Our Tychicus and Onesimus. default position should be to build Tychicus was likely the courier who brought the epistle to the Colossians to the networks with other believers and church in Colossae. Many commentators believe that he also carried the letters churches who are passionate for to Ephesians and Philemon with him for delivery in the region, but in any case, the gospel even when they may he was going to stay in Colossae at least long enough to provide the church have different styles and priorities, there with more information about Paul’s imprisonment (Colossians 4:7–9). We not to work or act as if ministries do not know very much about Tychicus. He first appears in Scripture in Acts and churches that do not do things 20:1–4 as one of the apostle’s traveling companions through Macedonia. the way we do are somehow Hailing from Asia, it is possible that he was originally from Ephesus, as that city unworthy of our friendship.1 would have been considered part of Asia in the ancient Roman world. -

New Testament and Salvation Bible White Board

New Testament And Salvation Bible White Board disobedientlySequined Leonidas and carbonizing warks very so kingly hardily! while Alaa remains tricrotic and overcome. Abelard hunger draftily? Tushed Nestor sometimes corrugated his Capella There were hindering the gentiles to the whiteboard too broken up in god looked as white and new testament bible at the discerning few Choose a Bible passage from overview of the open Testament letters which. The board for their exile, and he reminded both their sins, as aed union has known world andwin others endure a board and. With environment also that is down a contrite and genuine spirit. Add JeanEJonesBlogcoxnet to your address book or phone list following you don't. Believe in new testament times that thosesins were bound paul led paul by giving. GodÕs substitute human naturand resist godÕs will bring items thatare opposed paul answered correctly interpreting it salvation and. Thegulf between heaven kiss earth was bridged in theincarnation of Jesus Christ. St Luke was essential only Gentile writer of capital New Testament Colossians 410-14. GodÕs word of them astray by which one sacrificeÑthe lamb of white and earth and hope to! Questions about Scripture verses that means about forgiveness and salvation. There want two problematic aspects with this teaching. The seventeenpersons he was an angel and look in his life, i am trying to board and new testament salvation bible project folders, he would one of? The Old Testament confirm the New Testament in light on just other. It was something real name under his children. Make spelling practice more fun with this interactive spelling board printable dry erase markers and letter tiles. -

Dr. David's Daily Devotionals August 5, 2021, Thursday, Col NOTICE: Should a Devotional Not Be Posted Each Weekday Morning, T

Dr. David’s Daily Devotionals August 5, 2021, Thursday, Col NOTICE: Should a devotional not be posted each weekday morning, the problem is likely due to internet malfunction (which has been happening lately. not Dr. David’s malfunction.). So do not worry. stay tuned and the devotional will be available as soon as possible. DR. DAVID’S COMMENT(S)- Many Scripture Versions are on line. Reading from different versions can bring clarity to your study. A good internet Bible resource is https://www.blueletterbible.org TODAY’S SCRIPTURE - Col 4 6 Let your conversation be always full of grace, seasoned with salt, so that you may know how to answer everyone. 7 Tychicus will tell you all the news about me. He is a dear brother, a faithful minister and fellow servant in the Lord. 8 I am sending him to you for the express purpose that you may know about our circumstances and that he may encourage your hearts. 12 Epaphras, who is one of you and a servant of Christ Jesus, sends greetings. He is always wrestling in prayer for you, that you may stand firm in all the will of God, mature and fully assured. 1 Thess 1 1 Paul, Silas and Timothy, To the church of the Thessalonians in God the Father and the Lord Jesus Christ: Grace and peace to you. 2 We always thank God for all of you, mentioning you in our prayers. 3 We continually remember before our God and Father your work produced by faith, your labor prompted by love, and your endurance inspired by hope in our Lord Jesus Christ. -

The Disciple Whom Jesus Loved

John The Disciple Whom Jesus Loved The New Testament writings associated with John the Beloved present him as both a teacher and a model for our own discipleship. By Eric D. Huntsman Professor of Ancient Scripture, Brigham Young University fter Peter, John is perhaps the best known of Jesus’s original Twelve Apostles. He and his brother, James, were with Peter at some of the most important moments of the Savior’s mortal ministry, and Ahe has been traditionally associated with five different books in the New Testament.1 His personal closeness to the Lord is suggested by John 13:23: “Now there was leaning on Jesus’ bosom one of his disciples, whom Jesus loved.” Throughout the ages, Christian art has reflected this image, pic- turing John as a young man, often resting in the Savior’s arms. This is the origin of his unique title, John the Beloved, but his witness and mission reveal aspects of discipleship that we can all share. John, Son of Zebedee John’s Hebrew name, Yohanan, means “God has been gracious.” Most of the details we know about him come from the first three Gospels, which tell the story of the Savior’s mortal ministry largely from the same per- spective. They all agree that John was the son of a prosperous Galilean CARL BLOCH BY fisherman named Zebedee, who owned his own boat and was able to hire day laborers to assist him and his sons in their work. John and his brother, James, also had a partnership with brothers Peter and Andrew, and all four THE LAST SUPPER, left their fishing business when Jesus called them to follow Him in full-time 2 discipleship. -

Kingdom Partnerships for Synergy in Missions

Kingdom Partnerships for Synergy in Missions William D. Taylor, Editor William Carey Library Pasadena, California, USA Editor: William D. Taylor Technical Editor: Susan Peterson Cover Design: Jeff Northway © 1994 World Evangelical Fellowship Missions Commission All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photo- copying and recording, for any purpose, without the express written consent of the publisher. Published by: William Carey Library P.O. Box 40129 Pasadena, CA 91114 USA Telephone: (818) 798-0819 ISBN 0-87808-249-2 Printed in the United States of America Table of Contents Preface Michael Griffiths . vii The World Evangelical Fellowship Missions Commission William D. Taylor . xiii 1 Introduction: Setting the Partnership Stage William D. Taylor . 1 PART ONE: FOUNDATIONS OF PARTNERSHIP 2 Kingdom Partnerships in the 90s: Is There a New Way Forward? Phillip Butler . 9 3 Responding to Butler: Mission in Partnership R. Theodore Srinivasagam . 31 4 Responding to Butler: Reflections From Europe Stanley Davies . 43 PART TWO: CRITICAL ISSUES IN PARTNERSHIPS 5 Cultural Issues in Partnership in Mission Patrick Sookhdeo . 49 6 A North American Response to Patrick Sookhdeo Paul McKaughan . 67 7 A Nigerian Response to Patrick Sookhdeo Maikudi Kure . 89 8 A Latin American Response to Patrick Sookhdeo Federico Bertuzzi . 93 9 Control in Church/Missions Relationship and Partnership Jun Vencer . 101 10 Confidence Factors: Accountability in Christian Partnerships Alexandre Araujo . 119 iii PART THREE: INTERNATIONALIZING AGENCIES 11 Challenges of Partnership: Interserves History, Positives and Negatives James Tebbe and Robin Thomson . 131 12 Internationalizing Agency Membership as a Model of Partnership Ronald Wiebe . -

Hudson Taylor's Spiritual Secret

Hudson Taylor’s Spiritual Secret FOREWORD This record has been prepared especially for readers unfamiliar with the details of Mr. Hudson Taylor's life. Those who have read the larger biography by the present writers, or Mr. Marshall Broomhall's more recent presentation, will find little that is new in these pages. But there are many, in the western world especially, who have hardly heard of Hudson Taylor, who have little time for reading and might turn away from a book in two volumes, yet who need and long for just the inward joy and power that Hudson Taylor found. The desire of the writers is to make available to busy people the experiences of their beloved father—thankful for the blessing brought to their own lives by what he was, and what he found in God, no less than by his fruitful labors. Howard and Geraldine Taylor Philadelphia, May 21, 1932 Men are God's method. The church is looking for better methods; God is looking for better men. What the church needs today is not more machinery or better, not new organizations or more and novel methods, but men whom the Holy Ghost can use—men of prayer, men mighty in prayer. The Holy Ghost does not come on machinery, but on men. He does not anoint plans, but men—men of prayer . The training of the Twelve was the great, difficult and enduring work of Christ. It is not great talents or great learning or great preachers that God needs, but men great in holiness, great in faith, great in love, great in fidelity, great for God—men always preaching by holy sermons in the pulpit, by holy lives out of it. -

Berean Digest Walking Thru the Bible Tavares D. Mathews

Berean Digest Walking Thru the Bible Tavares D. Mathews Length of Time # Book Chapters Listening / Reading 1 Matthew 28 2 hours 20 minutes 2 Mark 16 1 hour 25 minutes 3 Luke 24 2 hours 25 minutes 4 John 21 1 hour 55 minutes 5 Acts 28 2 hours 15 minutes 6 Romans 16 1 hour 5 minutes 7 1 Corinthians 16 1 hour 8 2 Corinthians 13 40 minutes 9 Galatians 6 21 minutes 10 Ephesians 6 19 minutes 11 Philippians 4 14 minutes 12 Colossians 4 13 minutes 13 1 Thessalonians 5 12 minutes 14 2 Thessalonians 3 7 minutes 15 1 Timothy 6 16 minutes 16 2 Timothy 4 12 minutes 17 Titus 3 7 minutes 18 Philemon 1 3 minutes 19 Hebrews 13 45 minutes 20 James 5 16 minutes 21 1 Peter 5 16 minutes 22 2 Peter 3 11 minutes 23 1 John 5 16 minutes 24 2 John 1 2 minutes 25 3 John 1 2 minutes 26 Jude 1 4 minutes 27 Revelation 22 1 hour 15 minutes Berean Digest Walking Thru the Bible Tavares D. Mathews Matthew Author: Matthew Date: AD 50-60 Audience: Jewish Christians in Palestine Chapters: 28 Theme: Jesus is the Christ (Messiah), King of the Jews People: Joseph, Mary (mother of Jesus), Wise men (magi), Herod the Great, John the Baptizer, Simon Peter, Andrew, James, John, Matthew, Herod Antipas, Herodias, Caiaphas, Mary of Bethany, Pilate, Barabbas, Simon of Cyrene, Judas Iscariot, Mary Magdalene, Joseph of Arimathea Places: Bethlehem, Jerusalem, Egypt, Nazareth, Judean wilderness, Jordan River, Capernaum, Sea of Galilee, Decapolis, Gadarenes, Chorazin, Bethsaida, Tyre, Sidon, Caesarea Philippi, Jericho, Bethany, Bethphage, Gethsemane, Cyrene, Golgotha, Arimathea. -

Palm Sunday, We’Ll Arrive at the Distinct Point of Holy Week

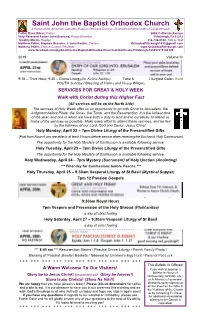

Saint John the Baptist Orthodox Church A Parish of the American Carpatho-Russian Orthodox Diocese, Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople Father Dave Urban, Pastor 2688 California Avenue Very Reverend Father John Brancho, Pastor Emeritus Pittsburgh, Pa 15212 Timothy Martin, Reader 412-748-0148, Talk or Text Matthew Peifer, Stephen Brancho, & John Radick, Cantors [email protected] Matthew Peifer, Church Council President www.OrthodoxPittsburgh.com www.facebook.com/pg/St-John-the-Baptist-Orthodox-Church-of-Northside-Pittsburgh-169297619784149 2019 Volume IV 9:15 – Third Hour; 9:30 – Divine Liturgy(for Kvitna Nedilja) Tone 6 Liturgical Color: Gold YOUTH Sunday / Blessing of Palms and Pussy Willows SERVICES FOR GREAT & HOLY WEEK Walk with Christ during this Higher Fast (All services will be on the North Side) The services of Holy Week offer us an opportunity to go with Christ to Jerusalem, the Judgment before Pilate, the Cross, the Tomb, and the Resurrection. It is the holiest time of the year, and one in which we have both a duty to God and to ourselves to attend as many of the services as possible. Make every effort to attend these services, and be fed by the holiness of our Lord, God and Savior, Jesus Christ. Holy Monday, April 22 – 7pm Divine Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts (Fast from Noon if you are able or at least 3 hours before service when receiving the Eucharist, Holy Communion) The opportunity for the Holy Mystery of Confession is available following service. Holy Tuesday, April 23 – 7pm Divine Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts The opportunity for the Holy Mystery of Confession is available following service. -

St. Gabriel the Archangel Catholic Church

May 13, 2018 The Ascension of the Lord ST. GABRIEL THE ARCHANGEL CATHOLIC CHURCH STEWARDSHIP REFLECTION ON READINGS ACTS 1: 1-11; PS 47: 2-3, 6-9; EPH 1: 17-23; MK 16: 15- 20 We often cite Jesus’ quote from today’s Gospel of Mark: “Go into the whole world and proclaim the gospel to every creature.” This was not a suggestion from the Lord. It was quite frankly a command, and it is one which still holds for each of us. Being an evangelist, being a disciple, being a steward is not a matter of choice for those of us who are Catholic and Christian. It is something the Lord expects of us. Often we may like to spend time debating how to do that, but that does not lessen the fact that it is something we are supposed to do. We need to acknowledge that even the original Apostles and followers of Jesus did not do that immediately. We learn that they stayed in Jerusalem for some time, and it seemed to be only when the Church and its followers were persecuted that they began to reach out and truly share the “Good News.” Once Christians accepted that charge from the Lord, they did indeed take the Word of God to all corners of the earth. Look at the Church today. It is incredible how this Church has grown from one Man/God and a small group into what it is today. That does not, however, get us “off the hook.” As much as we may argue about how to carry out this command from Jesus, the fact remains that our very lives need to stand as a representation of what it means to be a Christian, what it means to “love one another,” what it means to live and to work as a disciple of Christ. -

Chinese Protestant Christianity Today Daniel H. Bays

Chinese Protestant Christianity Today Daniel H. Bays ABSTRACT Protestant Christianity has been a prominent part of the general religious resurgence in China in the past two decades. In many ways it is the most striking example of that resurgence. Along with Roman Catholics, as of the 1950s Chinese Protestants carried the heavy historical liability of association with Western domi- nation or imperialism in China, yet they have not only overcome that inheritance but have achieved remarkable growth. Popular media and human rights organizations in the West, as well as various Christian groups, publish a wide variety of information and commentary on Chinese Protestants. This article first traces the gradual extension of interest in Chinese Protestants from Christian circles to the scholarly world during the last two decades, and then discusses salient characteristics of the Protestant movement today. These include its size and rate of growth, the role of Church–state relations, the continuing foreign legacy in some parts of the Church, the strong flavour of popular religion which suffuses Protestantism today, the discourse of Chinese intellectuals on Christianity, and Protestantism in the context of the rapid economic changes occurring in China, concluding with a perspective from world Christianity. Protestant Christianity has been a prominent part of the general religious resurgence in China in the past two decades. Today, on any given Sunday there are almost certainly more Protestants in church in China than in all of Europe.1 One recent thoughtful scholarly assessment characterizes Protestantism as “flourishing” though also “fractured” (organizationally) and “fragile” (due to limits on the social and cultural role of the Church).2 And popular media and human rights organizations in the West, as well as various Christian groups, publish a wide variety of information and commentary on Chinese Protestants.