A Study of the Difficulties Involved in Introducing Young

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WPB Judo Academy Parents and Judoka Handbook

WPB Judo Academy 2008 Parents and Judoka Handbook Nage-Waza - Throwing Techniques O-soto-otoshi O-soto-gari Ippon-seio-nage De-ashi-barai Tai-otoshi Major Outer Drop Major Outer One Arm Shoulder Advancing Foot Body Drop Throw Sweep O-uchi-gari Ko-uchi-gari Ko-uchi-gake Ko-soto-gake Ko-soto-gari Major Inner Reaping Minor Inner Reaping Minor Inner Hook Minor Outer Hook Minor Outer Reap Uki-goshi O-goshi Tsuri-goshi Floating Hip Throw Major Hip Throw Lifting Hip Throw Osae-Waza - Holding Techniques Kesa-gatame Yoko-shiho-gatame Kuzure-kesa-gatme Scarf Hold Side 4 Quarters Broken Scarf Hold Nage-Waza - Throwing Techniques Morote-seio-nage O-goshi Uki-goshi Tsuri-goshi Koshi-guruma Two Arm Shoulder Major Hip Throw Floating Hip Throw Lifting Hip Throw Hip Whirl Throw Sode-tsuri-komi-goshi Tsuri-komi-goshi Sasae-tsuri-komi-ashi Tsubame-gaeshi Okuri-ashi-barai Sleeve Lifting Pulling Lifting Pulling Hip Lifting Pulling Ankle Swallow’s Counter Following Foot Hip Throw Throw Block Sweep Shime-Waza - Strangulations Nami-juji-jime Normal Cross Choke Ko-soto-gake Ko-soto-gari Ko-uchi-gari Ko-uchi-gake Minor Outer Hook Minor Outer Reap Minor Inner Reap Minor Inner Hook Osae-Waza - Holding Techniques Kansetsu-Waza - Joint Locks Gyaku-juji-jime Reverse Cross Choke Kami-shiho-gatame Kuzure-kami-shiho-gatame Upper 4 Quarters Hold Broken Upper 4 Quarters Hold Ude-hishigi-juji-gatme Cross Arm Lock Tate-shiho-gatame Kata-juji-jime Mounted Hold Half Cross Choke Nage-Waza - Throwing Techniques Harai-goshi Kata-guruma Uki-otoshi Tsuri-komi-goshi Sode-tsuri-komi-goshi -

The Second Eight Judo Throws

DC JUDO The Second Eight Judo Throws (Dai Nikkyo from the Gokyo No Waza) DC JUDO Second Eight Throws Page 1 of 5 KOSOTO GARI Tori breaks uke’s balance towards his rear or his right rear corner, then he reaps uke’s right heel (which carries his weight) from behind with his left foot so that he falls on his back. KOUCHI GARI Tori reaps the inside of uke’s right heel with the sole of his right foot so that he falls backwards. DC JUDO Second Eight Throws Page 2 of 5 KOSHI GURUMA Tori holds and controls uke’s neck with his right (left) arm, enters his waist deep, and, loading uke onto it, throws him in a circle around the fulcrum of his torso. (Illustrated on the right side) TSURIKOMI GOSHI Tori breaks uke’s balance straight forward, or to his right (left) front corner, lifts and pulls him onto the back of his waist, and throws him. (Illustrated on the right side in the picture) DC JUDO Second Eight Throws Page 3 of 5 OKURI ASHI HARAI Tori sweeps (or sends) uke’s right (left) foot to uke’s left (right) with his left (right) foot, and sweeps both legs up to complete the throw. (Illustrated on the left side) TAI OTOSHI Tori breaks uke’s balance to his right (or left) front corner, opens his body to the left, steps his right (left) foot in front of uke’s right (left) foot, pulls uke forward, and throws him down. (Illustrated on the right side) DC JUDO Second Eight Throws Page 4 of 5 HARAI GOSHI Tori breaks uke’s balance straight forwards, or to his right (left) front corner, pulls him onto the back of his his right (left) hip, and sweeps him up with the right (left) leg. -

Nokido Ju-Jitsu & Judo Student Handbook

Nokido Ju-Jitsu & Judo Student Handbook North Port, Florida Shihan Earl DelValle HISTORY OF JU-JITSU AND NOKIDO JU-JITSU Ju-Jitsu (Japanese: 柔術), is a Japanese Martial Art and a method of self defense. The word Ju- Jitsu is often spelled as Jujutsu, Jujitsu, Jiu-jutsu or Jiu-jitsu. "Jū" can be translated to mean "gentle, supple, flexible, pliable, or yielding." "Jitsu" can be translated to mean "art" or "technique" and represents manipulating the opponent's force against himself rather than directly opposing it. Ju-Jitsu was developed among the samurai of feudal Japan as a method for defeating an armed and unarmed opponent in which one uses no weapon. There are many styles (ryu) and variations of the art, which leads to a diversity of approaches, but you will find that the different styles have similar, if not the same techniques incorporated into their particular style. Ju-Jitsu schools (ryū) may utilize all forms of grappling techniques to some degree (i.e. throwing, trapping, restraining, joint locks, and hold downs, disengagements, escaping, blocking, striking, and kicking). Japanese Ju-Jitsu grew during the Feudal era of Japan and was expanded by the Samurai Warriors. The first written record of Ju-Jitsu was in 1532 by Hisamori Takeuchi. Takenouchi Ryu Ju-Jitsu is the oldest style of Ju-jitsu and is still practiced in Japan. There are hundreds of different Ju-Jitsu styles that have been documented and are practiced today, one of which is our modern style of Ju-Jitsu, Nokido Ju-Jitsu. Ju-Jitsu is said to be the father of all Japanese Martial Arts. -

WD PG Kyu Grading Syllabus

Western University Judo Club Kyu Grading Syllabus A Trail Form White Belt To Brown Belt Western University Judo Club Kyu Grading Syllabus 5th Kyu YELLOW Belt KIHON (Basics) REI (Bow) Ritsu-rei: Standing bow Za-rei: Sitting bow SHISEI (Postions) Shizen-hon-tai: Basic natural guard (Migi/Hidari-shizen-tai: Right/Left) Jigo-hon-tai: Basic defensive guard (Migi/Hidari-jigo-tai: Right/Left) SHINTAI (walks, movements) Tsuri-ashi: Feet shuffling (in common with Ayumi-ashi, Tsugi-ashi and Tai-sabaki) Ayumi-ashi: Normal walk, “foot passes foot” (Mae/Ushiro: Forwards/Backwards) Tsugi-ashi: Walk “foot chases foot” (Mae/Ushiro, Migi/Hidari) Tai-sabaki: Pivot (90/180°, Mae-Migi/Hidari, Ushiro-Migi/Hidari); KUMI-KATA: Grips (Hon-Kumi-Kata, Basic grip, Migi/Hidari-K.-K., Right/Left) WAZA: Technique KUZUSHI, TSUKURI, KAKE: Unbalancing, Positioning, Throw (Phases of the techniques) HAPPO-NO-KUZUSHI: The eight directions of unbalancing UKEMI (Break-falls) Ushiro-ukemi: Backwards break-fall Yoko-ukemi: Side break-fall (Migi/Hidari-yoko-ukemi) Mae-ukemi: Forward break-fall Mae-mawari-ukemi: Rolling break-fall Zempo-kaiten-ukemi: Leaping rolling break-fall KEIKO (Training exercises) Uchi-komi: Repetitions of entrances (lifting) Butsukari: Repetitions of impacts (no lifting) Kakke-ai: Repetitions of throws Yakusoku-geiko: One technique each without any reaction from Uke Kakari-geiko: One attacking, the other defending using the gentle way Randori: Free training exercise Shiai: Competition fight 2 Western University Judo Club Kyu Grading Syllabus NAGE-WAZA -

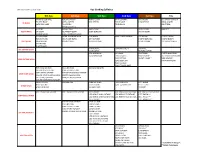

Kyu Grading Syllabus Summary

Western University Judo Club Kyu Grading Syllabus 5th Kyu 4th Kyu 3rd Kyu 2nd Kyu 1st Kyu Extra MOROTE SEOI NAGE KUCHIKI DAOSHI MOROTE GARI KATA GURUMA UKI OTOSHI UCHI MATA SUKASHI ERI SEOI NAGE KIBISU GAESHI SEOI OTOSHI SUKUI NAGE SUMI OTOSHI YAMA ARASHI TE WAZA KATA SEOI NAGE TAI OTOSHI TE GURUMA OBI OTOSHI IPPON SEOI NAGE O GOSHI HARAI GOSHI HANE GOSHI TSURI GOSHI DAKI AGE KOSHI WAZA UKI GOSHI TSURIKOMI GOSHI KOSHI GURUMA UTSURI GOSHI USHIRO GOSHI SODE TSURIKOMI GOSHI DE ASHI BARAI SASAE TSURIKOMI ASHI UCHI MATA ARAI TSURIKOMI ASHI O GURUMA O UCHI GAESHI HIZA GURUMA OKURI ASHI BARAI ASHI GURUMA O SOTO GURUMA O SOTO GAESHI ASHI WAZA KO UCHI GARI KO SOTO GARI O SOTO OTOSHI KO SOTO GAKE UCHI MATA GAESHI O UCHI GARI O SOTO GARI TOMOE NAGE HIKIKOMI GAESHI URA NAGE MA SUTEMI WAZA SUMI GAESHI TAWARA GAESHI UCHI MAKIKOMI UKI WAZA YOKO GAKE O SOTO MAKIKOMI SOTO MAKIKOMI TANI OTOSHI KANI BASAMI * UCHI MATA MAKIKOMI YOKO OTOSHI KAWAZU GAKE * DAKI WAKARE YOKO SUTEMI WAZA YOKO GURUMA HARAI MAKIKOMI YOKO WAKARE YOKO TOMOE NAGE HON KESA GATAME KATA GATAME SANKAKU GATAME KUZURE KESA GATAME KAMI SHIHO GATAME YOKO SHIHO GATAME KUZURE KAMI SHIHO GATAME OSAE KOMI WAZA KUZURE YOKO SHIHO GATAME USHIRO KESA GATAME TATE SHIHO GATAME MAKURA KESA GATAME KUZURE TATE SHIHO GATAME KATA JUJI JIME HADAKA JIME OKURI ERI JUME TSUKKOMI JIME RYO TE JIME NAMI JUJI JIME KATA HA JIME SODE GURUMA JIME KATA TE JIME SHIME WAZA GYAKU JUJI JIME SANKAKU JIME DO JIME * UDE HISHIGI JUJI GATAME UDE HISHIGI HARA GATAME UDE GARAMI UDE HISHIGI UDE GATAME UDE HISHIGI ASHI GATAME UDE -

Seishin Judo Promotion Requirements

SEISHINJUDO AT SANDIA JUDO CLUB LINDA YIANNAKIS, 5TH DAN (USA-TKJ); 5TH DAN (USA JUDO) Requirements for Promotion The serious study of judo requires regular attendance, much persistence, an understanding of principles both physical and philosophical, and practice, practice, practice. Seishin Judo is committed to the study of the larger judo: judo as a way of life and a path as well as a powerful martial way. Classes focus on the principles that drive techniques and their application in various contexts. Students may advance in rank by meeting time in grade criteria and by demonstrating technical competence and theoretical and background knowledge. Randori, kata (formal and informal) and competition are the three main areas of judo application. Expectations and requirements in all three areas are stated at each grade level. In addition, attending clinics and seminars and providing supervised teaching (when appropriate) are required. Each test below includes a representative sampling of principles and techniques from judo. The tests do not represent a complete syllabus of judo. They also include techniques that are outside of the standard Kodokan program. This document is intended as a reference and study guide for the student. GOKYU (5th Kyu) Yellow Belt (All Testing is from Japanese Terminology) 1. Sound character and maturity 2. Minimum age of 14 years 3. Minimum time practicing Judo: 3 months 4. Regular dojo attendance 5. Good dojo hygiene 6. Good Judo/Jujutsu etiquette 7. Demonstrate competence in basic breakfalls 8. Demonstrate kiai and understanding of Judo spirit 9. Proper wearing and folding of the Judogi 10. Demonstrate standing and kneeling bows (ritsurei and zarei) 11. -

Midwest Academy Fundamentals Kihon Glossary

Midwest Academy of Martial Arts (630) 836 – 3600 Naperville, Il www.TheMidwestAcademy.com Seizan Ryu Kempo Jujutsu Fundamentals / Kihon English Japanese Positioning Tsukuri Notes Stances Shisei 1. Neutral stance 1. Chuitsu dachi 1. 2. Foundation stance 2. Kiso dachi 2. 3. Natural ready stance 3. Shizen yoi dachi 3. 4. Forward stance 4. Zenkutsu dachi 4. 5. Forward hook stance 5. Manji dachi 5. 6. Back stance 6. Kokutsu dachi 6. 7. Cat stance 7. Neko ashi dachi 7. 8. Crane Stance 8. Tsuru dachi 8. 9. Cross Stance 9. Juji dachi 9. 10. Hourglass Stance 10. Sunadokei dachi 10. 11. Pyramid 11. Shiho shisei 11. 12. Triangle/Offset triangle 12. Sankaku shisei 12. 13. Hurdler 13. Shogai shisei 13. Postures / Guards Kamae 1. Salutation Posture 1. Gassho gamae 1. 2. Standing attention posture 2. Kiritsu chumoku gamae 2. 3. Standing bow 3. Kiritsu rei 3. 4. Seated attention posture 4. Suwari chumoku gamae 4. 5. Seated bow 5. Suwari rei 5. 6. Meditation posture 6. Seiza gamae 6. 7. Fundamental posture 7. Kihon gamae 7. 8. High ready guard 8. Jodan yoi gamae 8. 9. Middle ready guard 9. Chudan yoi gamae 9. 10. Low ready guard 10. Gedan yoi gamae 10. 11. Single knee guard 11. Ippon hizamazuki gamae 11. Dodges Sorashi 1. Side dodge 1. Yoko sorashi 1. 2. Circular dodge 2. Marui sorashi 2. 3. Half Turn 3. Han tenkan 3. 4. Leg wave 4. Nami ashi 4. 5. Backwards dodge 5. Sorimi 5. 6. Pull in dodge 6. Hikimi 6. Footwork Ashi waza 1. Gliding step 1. -

Junior First (1St) Degree – Yellow

Junior Fifth (5th) Degree – Green Requirements (Minimum) Age – 8 Name __________________ Time in Previous Degree – 4 months Date Started ____________ Class Attendance – 32 classes Date Completed __________ Promotions Points – 8 points (see point calculation sheet) Previous Degree Requirements All of this Degree Requirements signed off by a Sensei General Information 1. List three of the seven men who attained 10th degree black belt while they were still alive? Nagaoka, Mifune, Yamashita, Isogai, Iizuka, Samura, Tornita 2. What is Kata? A formal prearranged practice routine 3. How many Kata are there in Kodokan Judo? Nine 4. Which Kata is considered most useful for learning throwing techniques? Nage no Kata 5. Which Kata is considered most useful for learning grappling techniques? Gatame no Kata Judo Vocabulary 1. Technique = Waza 13. Body = Tai 2. Hand Technique = Te Waza 14. Body movement = Shintai 3. Foot Technique = Ashi Waza 15. Pivoting or turning the body = Tai Sabaki 4. Holding Technique = Osaekomi Waza 16. To Drop = Otoshi 5. Counter Technique = Kaeshi Waza 17. Valley = Tani 6. Judo Uniform = Judogi 18. Forth degree black belt = Yodan 7. Judo Uniform Sleeve = Sode 19. Valley Drop = Tani Otoshi 8. Judo Uniform Belt = Obi 20. Floating drop = Uki Otoshi 9. Judo Practitioner or Player = Judoka 21. Body drop = Tai Otoshi 10. Practice hall for Judo = Dojo 22. Shoulder Wheel = Kata Guruma 11. Rolling = Kaiten 23. Shoulder hold = Kata Gatame 12. Front rolling falls = Zempo Kaiten Ukemi 24. Straddling hold = Tate Shiho Gatame Page 1 of -

What You Will Be Tested on for Each Rank

What you will be tested on for each rank White 1S Osoto Otoshi Ogoshi Yellow Osoto Otoshi Ogoshi Ippon Seoi Nage Osoto Gari Kesa Gatame Kuzure Kesa Gatame Yellow 1S Ippon Seoi Nage Osoto Gari Kesa Gatame Kuzure Kesa Gatame Tai otoshi Koshi Guruma Makura Kesa Gatame Ushiro Kesa Gatame Yellow 2S Tai otoshi Koshi Guruma Makura Kesa Gatame Ushiro Kesa Gatame Morote Seoi Nage Uki Goshi Yoko Shiho Gatame Kuzure Yoko Shihi Gatame Orange Morote Seoi Nage Uki Goshi Yoko Shiho Gatame Kuzure Yoko Shihi Gatame Ouchi Gari Hiza Guruma Kami Shiho Gatame Kazure Kami Shiho Gatame Orange 1S Ouchi Gari Hiza Guruma Kami Shiho Gatame Kazure Kami Shiho Gatame Kouchi Gari Sasae Tsurikomi Ashi Tate Shiho Gatame Kuzure Tate Shiho Gatame Orange 2S Kouchi Gari Sasae Tsurikomi Ashi Tate Shiho Gatame Kuzure Tate Shiho Gatame Tsurikomi Goshi Sode Tsurikomi Goshi Kata Gatame Green Tsurikomi Goshi Sode Tsurikomi Goshi Kata Gatame Harai Goshi Okuri Ashi Barai Hadaka Jime Green 1S Harai Goshi Okuri Ashi Barai Hadaka Jime Uchi Mata Deashi Barai Okuri Eri Jime Kata Ha Jime Green 2S Uchi Mata Deashi Barai Okuri Eri Jime Kata Ha Jime Kosoto Gari Harai Tsurikomi Ashi Ryote Jime Blue Kosoto Gari Harai Tsurikomi Ashi Ryote Jime Hane Goshi Ushiro Goshi Gyaku Juji Jime Nami Juji Jime Kata Juji Jime Blue 1S Hane Goshi Ushiro Goshi Gyaku Juji Jime Nami Juji Jime Kata Juji Jime Ashi Guruma Tomoe Nage Ashi Gatame Jime Sode Guruma Jime Blue 2S Ashi Guruma Tomoe Nage Ashi Gatame Jime Sode Guruma Jime Kata Guruma Oguruma Ude Gatame Purple Kata Guruma Oguruma Ude Gatame Uki Waza Yoko Guruma Juji Gatame Ude Garami Purple 1S Uki Waza Yoko Guruma Juji Gatame Ude Garami Soto Makikomi Yoko Otoshi Hiza Gatame Purple 2S Soto Makikomi Yoko Otoshi Hiza Gatame Sukui Nage Utsuri Goshi Waki Gatame Hara Gatame. -

Japanese Judo Vocabulary

Japanese Judo Vocabulary Principles of Judo Ju the principle of gentleness, yielding, or giving way Do way, path, or principle Judo the gentle way Seiryoku Zenyo maximum efficiency (through minimum effort) Jita Kyoei mutual benefit and welfare General Vocabulary Sensei teacher or instructor Dojo place or club where Judo is practiced Gi (Judogi) Judo uniform Seiza kneeling position Anza sitting position with legs crossed Ritsurei standing bow Zarei kneeling bow Kiotsuke! (come to) attention! Rei! bow! Sensei Ni Rei! bow! (to Sensei) Uke person receiving a judo technique Tori person performing a judo technique Ukemi falling practice (side, back, forward) Uchi Komi repetition practice without throwing Randori free practice Kiai shout during execution of technique Gripping, Posture and Throwing Principles Kumi Kata methods of gripping an opponent Shizen Hontai fundamental natural posture Jigo Hontai (Jigotai) fundamental defensive posture Tsugi Ashi sliding foot walking (kata technique) Tai Sabaki pivoting or turning the body Kuzushi off balance (first element of a throw) Tsukuri entry into a throw Kake execution of a throw Vocabulary Related to Names of Judo Techniques Ashi foot or leg (as in Okuri-Ashi-Harai) Barai sweeping action with the leg or foot (as in Deashi-Barai) Dori grab (as in Kata-Ashi-Dori) Dojime body scissors/squeeze (illegal in competition) Eri lapel of the Judo gi (as in Okuri-Eri-Jime) Gaeshi (Kaeshi) counter or reversal (as in Sumi-Gaeshi) Gake hook (as in Ko-Soto-Gake) Garami entangle or twist (as in Ude-Garami) Gari -

Posters JUDO - KU

KFVIDEO ??? ???????? ????? Mr ??????? ?????? ?????????? 124460 ?????? Russian Federation ?????? +7-916-124-59-49 Posters JUDO - KU. Set of 18 pieces.The technique of judo. Page 1/4 KFVIDEO ??? ???????? ????? Mr ??????? ?????? ?????????? 124460 ?????? Russian Federation ?????? +7-916-124-59-49 Page 2/4 KFVIDEO ??? ???????? ????? Mr ??????? ?????? ?????????? 124460 ?????? Russian Federation ?????? +7-916-124-59-49 Posters Judo - KU.Set of 18 pieces. A2-420 × 594 mm White belt 6 Kyu 1 poster. Yellow belt 5 Kyu 3 poster. Orange belt 4 Kyu 3 poster. Green belt 3 Kyu 4 poster. Blue belt 2 Kyu 4 poster. Brown belt 1 Kyu 2 poster. 1 poster. Material: prohibited methods Rating:PriceBase price Not withRated tax Yet 3500,00 ??? 3500,00 ??? Ask a question about this product PostersDescription Judo - KU.Set of 18 pieces. A2-420 × 594 mm Judo techniques list. Page 3/4 KFVIDEO ??? ???????? ????? Mr ??????? ?????? ?????????? 124460 ?????? Russian Federation ?????? +7-916-124-59-49 Judo posters for sale. White belt 6 Kyu 1 poster. Yellow belt 5 Kyu 3 poster. Orange belt 4 Kyu 3 poster. Green belt 3 Kyu 4 poster. Blue belt 2 Kyu 4 poster. Brown belt 1 Kyu 2 poster. 1 poster. Material: prohibited methods Posters Judo -KU. Set of 18 pieces.A4. size A4- 210 × 297 mm White belt 6 Kyu 1 poster. Rei. Obi. Shisei. Shintai. Tai-sabaki. Kumi-kata. Kuzushi. Ukemi. Yellow belt 5 Kyu 3 poster. NAGE WAZA De-ashi-barai,Hiza-guruma,Sasae-tsurikomi-ashi,Uki-goshi,O-soto-gari,O-goshi,O-uchi- gari,Seoi-nage,O-soto-otoshi,O-soto-gaeshi,O-uchi-gaeshi,Morote-seoi-nage. KATAME-WAZA Hon-kesa-gatame,Kata-gatame,Yoko-shiho-gatame,Kami-shiho-gatame,Tate-shiho-gatami. -

Gokyo-No-Waza Throwing Techniques Gokyo

Gokyo-No-Waza Throwing Techniques Gokyo - Yellow Belt De Ashi Barai Advanced foot sweep Osoto Gari Major outer reaping O Goshi Major Hip Ouchi Gari Major inner reaping Morote Seoi Nage Two arm shoulder Ippon Seoi Nage One arm shoulder Yonkyu - Orange Belt Uki Goshi Floating hip Ko Soto Gari Minor outer reaping Kouchi Gari Minor inner reaping Tai Otoshi Body drop Harai Goshi Sweeping loin Kosoto Gake Minor outer block Tomoe Nage Stomach throw Utsuri goshi Changing hip Sankyu - Green Belt Hiza Guruma Knee wheel Koshi Guruma Hip wheel Sasae Tsurikomi Ashi Drawing propping ankle Tsurikomi Goshi Lifting propping hip Okuri Ashi Barai Double foot sweep Hane Goshi Spring hip Kata Guruma* Shoulder wheel Tani Otoshi Valley drop Yoko Gake Side body drop Morote gari Two hand reap Nikyu - Blue Belt Seoi Otoshi Shoulder drop Eri Seoi Nage Collar shoulder Ippon Goshi One arm hip Uchi Mata Inner thigh Otsuri Goshi Major lifting hip Kotsuri Goshi Minor lifting hip Yoko Otoshi Side drop Sumi Gaeshi Corner throw O Guruma Major wheel Uki Otoshi Floating drop Yoko Wakare Side separation Kuchiki Taoshi One hand drop Yama Arashi Mountain storm Obi Tori Gaeshi Belt grab Ko Ouchi Makikomi Minor inner wraparound Kibisu Gaeshi Heel trip Ikkyu - Brown Belt Ashi Guruma Leg Wheel Sumi Otoshi Corner Drop Hane Makikomi Springing wraparound Sukuinage Scooping throw Soto Makikomi Outer wraparound Osoto Guruma Major outer wheel Ushiro Goshi Rear hip Ura Nage Rear throw Harai Tsurikomi Ashi Sweeping propping ankle Tsubame Gaeshi Swallow throw Uchi Mata Sukashi Inner thigh