Or Adat) Cannot Be Separated Due to Tradition Had to Be Evolved Based on Islamic Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Did America Inspire Indonesian Revolution?

How Did America Inspire Indonesian Revolution? I Basis Susilo & Annisa Pratamasari Universitas Airlangga ABSTRACT This paper examines the American Revolution as an inspiration for Indonesia’s founding fathers to fight for their nation’s independence in 1945. This paper was sparked by the existence of the pamphlet ‘It’s 1776 in Indonesia’ published in 1948 in the United States which presupposes the link between Indonesian Revolution and the American Revolution. The basic assumption of this paper is that Indonesian founding fathers were inspired by the experiences of other nations, including the Americans who abolished the British colonization of 13 colonies in North American continent in the eigthenth century. American inspiration on the struggle for Indonesian independence was examined from the spoken dan written words of three Indonesian founding fathers: Achmad Soekarno, Mohamad Hatta, and Soetan Sjahrir. This examination produced two findings. First, the two Indonesian founding fathers were inspired by the United States in different capacities. Compared to Hatta and Sjahrir, Soekarno referred and mentioned the United States more frequent. Second, compared to the inspirations from other nations, American inspiration for the three figures was not so strong. This was because the liberal democratic system and the American-chosen capitalist system were not the best alternative for Soekarno, Hatta, and Sjahrir. Therefore, the massive exposition of the 1776 Revolution in 1948 was more of a tactic on the Indonesian struggle to achieve its national objectives at that time, as it considered the United States as the most decisive international post-World War II political arena. Keywords: United States, Indonesia, Revolution, Inspiration, Soekarno, Hatta, Sjahrir. -

Review the Mind of Mohammad Hatta for the Contemporary of Indonesian Democracy

Review the Mind of Mohammad Hatta for the Contemporary of Indonesian Democracy Farid Luthfi Assidiqi 1 {[email protected]} 1 Universitas Diponegoro, Indonesia 1 Abstract. Mohammad Hatta is one of the founders of the nation, as well as a thinker who controls various Western disciplines, but still adheres to Indonesian values. His thoughts on democracy include popular democracy and economic democracy with the principle of popular sovereignty. The results of this study are that all elements of the nation need to actualize the thinking of Mohammad Hatta trying to apply the concept of Democratic Democracy and Economic Democracy by re-learning his concept of thought and making policies that enable Mohammad Hatta's democratic concept to be implemented. Keywords: People's Sovereignty, Popular Democracy, Economic Democracy. 1 Introduction Mohammad Hatta or familiarly called Bung Hatta was one of the thinkers who became the founding father of the Indonesian nation. Bung Hatta, the first hero of the Indonesian Proclamator and Deputy President, has laid the foundations of nation and state through struggle and thought enshrined in the form of written works. Bung Hatta had been educated in the Netherlands but because Nationalism and his understanding of Indonesia made his work very feasible to study theoretically. Bung Hatta devoted his thoughts by writing various books and writing columns in various newspapers both at home and abroad. It has been known together that Bung Hatta's work was so diverse, his thinking about nationalism, Hatta implemented the idea of nationalism that had arisen since school through his politics of movement and leadership in the movement organization at the Indonesian Association and Indonesian National Education. -

The Islamic Traditions of Cirebon

the islamic traditions of cirebon Ibadat and adat among javanese muslims A. G. Muhaimin Department of Anthropology Division of Society and Environment Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies July 1995 Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Muhaimin, Abdul Ghoffir. The Islamic traditions of Cirebon : ibadat and adat among Javanese muslims. Bibliography. ISBN 1 920942 30 0 (pbk.) ISBN 1 920942 31 9 (online) 1. Islam - Indonesia - Cirebon - Rituals. 2. Muslims - Indonesia - Cirebon. 3. Rites and ceremonies - Indonesia - Cirebon. I. Title. 297.5095982 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Teresa Prowse Printed by University Printing Services, ANU This edition © 2006 ANU E Press the islamic traditions of cirebon Ibadat and adat among javanese muslims Islam in Southeast Asia Series Theses at The Australian National University are assessed by external examiners and students are expected to take into account the advice of their examiners before they submit to the University Library the final versions of their theses. For this series, this final version of the thesis has been used as the basis for publication, taking into account other changes that the author may have decided to undertake. In some cases, a few minor editorial revisions have made to the work. The acknowledgements in each of these publications provide information on the supervisors of the thesis and those who contributed to its development. -

A Note on the Sources for the 1945 Constitutional Debates in Indonesia

Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde Vol. 167, no. 2-3 (2011), pp. 196-209 URL: http://www.kitlv-journals.nl/index.php/btlv URN:NBN:NL:UI:10-1-101387 Copyright: content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License ISSN: 0006-2294 A.B. KUSUMA AND R.E. ELSON A note on the sources for the 1945 constitutional debates in Indonesia In 1962 J.H.A. Logemann published an article entitled ‘Nieuwe gegevens over het ontstaan van de Indonesische grondwet van 1945’ (New data on the creation of the Indonesian Constitution of 1945).1 Logemann’s analysis, presented 48 years ago, needs revisiting since it was based upon a single work compiled by Muhammad Yamin (1903-1962), Naskah persiapan Undang-undang Dasar 1945 (Documents for the preparation of the 1945 Constitution).2 Yamin’s work was purportedly an edition of the debates conducted by the Badan Penyelidik Usaha Persiapan Kemerdekaan (BPUPK, Committee to Investigate Preparations for Independence)3 between 29 May and 17 July 1945, and by the 1 Research for this article was assisted by funding from the Australian Research Council’s Dis- covery Grant Program. The writers wish to thank K.J.P.F.M. Jeurgens for his generous assistance in researching this article. 2 Yamin 1959-60. Logemann (1962:691) thought that the book comprised just two volumes, as Yamin himself had suggested in the preface to his first volume (Yamin 1959-60, I:9-10). Volumes 2 and 3 were published in 1960. 3 The official (Indonesian) name of this body was Badan oentoek Menjelidiki Oesaha-oesaha Persiapan Kemerdekaan (Committee to Investigate Preparations for Independence) (see Soeara Asia, 1-3-1945; Pandji Poestaka, 15-3-1945; Asia Raya, 28-5-1945), but it was often called the Badan Penjelidik Oesaha(-oesaha) Persiapan Kemerdekaan (see Asia Raya, 28-5-1945 and 30-5-1945; Sinar Baroe, 28-5-1945). -

Another Look at the Jakarta Charter Controversy of 1945

Another Look at the Jakarta Charter Controversy of 1945 R. E. Elson* On the morning of August 18, 1945, three days after the Japanese surrender and just a day after Indonesia's proclamation of independence, Mohammad Hatta, soon to be elected as vice-president of the infant republic, prevailed upon delegates at the first meeting of the Panitia Persiapan Kemerdekaan Indonesia (PPKI, Committee for the Preparation of Indonesian Independence) to adjust key aspects of the republic's draft constitution, notably its preamble. The changes enjoined by Hatta on members of the Preparation Committee, charged with finalizing and promulgating the constitution, were made quickly and with little dispute. Their effect, however, particularly the removal of seven words stipulating that all Muslims should observe Islamic law, was significantly to reduce the proposed formal role of Islam in Indonesian political and social life. Episodically thereafter, the actions of the PPKI that day came to be castigated by some Muslims as catastrophic for Islam in Indonesia—indeed, as an act of treason* 1—and efforts were put in train to restore the seven words to the constitution.2 In retracing the history of the drafting of the Jakarta Charter in June 1945, * This research was supported under the Australian Research Council's Discovery Projects funding scheme. I am grateful for the helpful comments on and assistance with an earlier draft of this article that I received from John Butcher, Ananda B. Kusuma, Gerry van Klinken, Tomoko Aoyama, Akh Muzakki, and especially an anonymous reviewer. 1 Anonymous, "Naskah Proklamasi 17 Agustus 1945: Pengkhianatan Pertama terhadap Piagam Jakarta?," Suara Hidayatullah 13,5 (2000): 13-14. -

Danilyn Rutherford

U n p a c k in g a N a t io n a l H e r o in e : T w o K a r t in is a n d T h e ir P e o p l e Danilyn Rutherford As Head of the Country, I deeply regret that among the people there are still those who doubt the heroism of Kartini___Haven't we already unanimously decided that Kartini is a National Heroine?1 On August 11,1986, as Dr. Frederick George Peter Jaquet cycled from Den Haag to his office in Leiden, no one would have guessed that he was transporting an Indonesian nation al treasure. The wooden box strapped to his bicycle looked perfectly ordinary. When he arrived at the Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, the scholar opened the box to view the Institute's long-awaited prize: a cache of postcards, photographs, and scraps of letters sent by Raden Adjeng Kartini and her sisters to the family of Mr. J. H. Abendanon, the colonial official who was both her patron and publisher. From this box so grudgingly surrendered by Abendanon's family spilled new light on the life of this Javanese nobleman's daughter, new clues to the mystery of her struggle. Dr. Jaquet's discovery, glowingly reported in the Indonesian press, was but the latest episode in a long series of attempts to liberate Kartini from the boxes which have contained her. For decades, Indonesian and foreign scholars alike have sought to penetrate the veils obscuring the real Kartini in order to reach the core of a personality repressed by colonial officials, Dutch artists and intellectuals, the strictures of tradition, and the tragedy of her untimely death. -

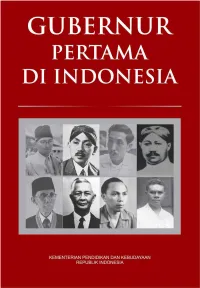

Teuku Mohammad Hasan (Sumatra), Soetardjo Kartohadikoesoemo (Jawa Barat), R

GUBERNUR PERTAMA DI INDONESIA GUBERNUR PERTAMA DI INDONESIA KEMENTERIAN PENDIDIKAN DAN KEBUDAYAAN REPUBLIK INDONESIA GUBERNUR PERTAMA DI INDONESIA PENGARAH Hilmar Farid (Direktur Jenderal Kebudayaan) Triana Wulandari (Direktur Sejarah) NARASUMBER Suharja, Mohammad Iskandar, Mirwan Andan EDITOR Mukhlis PaEni, Kasijanto Sastrodinomo PEMBACA UTAMA Anhar Gonggong, Susanto Zuhdi, Triana Wulandari PENULIS Andi Lili Evita, Helen, Hendi Johari, I Gusti Agung Ayu Ratih Linda Sunarti, Martin Sitompul, Raisa Kamila, Taufik Ahmad SEKRETARIAT DAN PRODUKSI Tirmizi, Isak Purba, Bariyo, Haryanto Maemunah, Dwi Artiningsih Budi Harjo Sayoga, Esti Warastika, Martina Safitry, Dirga Fawakih TATA LETAK DAN GRAFIS Rawan Kurniawan, M Abduh Husain PENERBIT: Direktorat Sejarah Direktorat Jenderal Kebudayaan Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan Jalan Jenderal Sudirman, Senayan Jakarta 10270 Tlp/Fax: 021-572504 2017 ISBN: 978-602-1289-72-3 SAMBUTAN Direktur Sejarah Dalam sejarah perjalanan bangsa, Indonesia telah melahirkan banyak tokoh yang kiprah dan pemikirannya tetap hidup, menginspirasi dan relevan hingga kini. Mereka adalah para tokoh yang dengan gigih berjuang menegakkan kedaulatan bangsa. Kisah perjuangan mereka penting untuk dicatat dan diabadikan sebagai bahan inspirasi generasi bangsa kini, dan akan datang, agar generasi bangsa yang tumbuh kelak tidak hanya cerdas, tetapi juga berkarakter. Oleh karena itu, dalam upaya mengabadikan nilai-nilai inspiratif para tokoh pahlawan tersebut Direktorat Sejarah, Direktorat Jenderal Kebudayaan, Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan menyelenggarakan kegiatan penulisan sejarah pahlawan nasional. Kisah pahlawan nasional secara umum telah banyak ditulis. Namun penulisan kisah pahlawan nasional kali ini akan menekankan peranan tokoh gubernur pertama Republik Indonesia yang menjabat pasca proklamasi kemerdekaan Indonesia. Para tokoh tersebut adalah Teuku Mohammad Hasan (Sumatra), Soetardjo Kartohadikoesoemo (Jawa Barat), R. Pandji Soeroso (Jawa Tengah), R. -

Bab Ii Kondisi Bangsa Indonesia Sebelum Sidang Bpupki A

BAB II KONDISI BANGSA INDONESIA SEBELUM SIDANG BPUPKI A.Masa Sebelum Sidang BPUPKI Setiap negara memiliki konstitusi. Demikian halnya bangsa Indonesia sebagai suatu negara juga memiliki konstitusi, yaitu Undang-Undang Dasar 1945. Pembentukan atau perumusan Undang-Undang Dasar 1945 ini menjadi konstitusi Indonesia melalui beberapa tahap.Pembuatan konstitusi ini diawali dengan proses perumusan Pancasila. Pancasila adalah dasar Negara Kesatuan Republik Indonesia. Pancasila berasal dari kata panca yang berarti lima, dan sila yang berarti dasar. Jadi, Pancasila memiliki arti lima dasar. Maksudnya, Pancasila memuat lima hal pokok yang diwujudkan dalam kelima silanya.1 Menjelang kemerdekaan Indonesia, tokoh-tokoh pendiri bangsa merumuskan dasar negara untuk pijakan dalam penyelenggaraan negara. Awal kelahiran Pancasila dimulai pada saat penjajahan Jepang di Indonesia hampir berakhir.Jepang yang mulai terdesak saat Perang Pasifik menjanjikan kemerdekaan kepada bangsa Indonesia. Untuk memenuhi janji tersebut, maka dibentuklah Badan Penyelidik Usaha-Usaha Persiapan Kemerdekaan Indonesia (BPUPKI) pada tanggal 28 Mei 1945. Badan ini beranggotakan 63 orang dan diketuai oleh dr. Radjiman Widyodiningrat. BPUPKI bertugas untuk mempersiapkan dan merumuskan hal-hal mengenai tata pemerintahan Indonesia jika merdeka. Untuk memperlancar tugasnya, BPUPKI membentuk beberapa panitia kerja, di antaranya sebagai berikut: 1. Panitia sembilan yang diketuai oleh Ir. Sukarno. Tugas panitia ini adalah merumuskan naskah rancangan pembukaan undang-undang dasar. 2. Panitia perancang UUD, juga diketuai oleh Ir. Sukarno. Di dalam panitia tersebut dibentuk lagi panitia kecil yang diketuai Prof. Dr. Supomo. 3. Panitia Ekonomi dan Keuangan yang diketuai Drs. Moh. Hatta. 4. Panitia Pembela Tanah Air, yang diketuai Abikusno Tjokrosuyoso. BPUPKI mengadakan sidang sebanyak dua kali. Sidang pertama BPUPKI terselenggara pada tanggal 29 Mei-1 Juni 1945. -

Pemikiran Soekarno Dalam Perumusan Pancasila

PEMIKIRAN SOEKARNO DALAM PERUMUSAN PANCASILA Paisol Burlian Guru Besar Ilmu Hukum Fakultas Syari’ah dan Hukum UIN Raden FatahPalembang Email : [email protected] Abstrak Dalam proses perumusan Pancasila dilakukan melalui beberapa tahapan persidangan, banyak tokoh yang dimasukkan di dalamnya seperti Muh. Yamin, Soepomo, dan Soekarno. Namun dari ketiga tokoh tersebut, hanya pemikiran Soekarno yang mendapat apresiasi dari peserta secara aklamasi dan pancasila yang dianggap sebagai keunggulan pemikiran Soekarno menjadi sesuatu yang berbeda dalam tatanan dan terminologi. Padahal sebelum Soekarno berpidato pada tanggal 1 Juni 1945, Muh. Yamin dan Soepomo sebelumnya pernah berpidato dan memiliki kemiripan satu sama lain. Penelitian ini menggunakan jenis fenomenologi kualitatif dengan studi pustaka, dengan menganalisis secara detail pada beberapa literatur yang relevan. Dengan menggunakan teori dekonstruksi milik Jacques Derrida dengan konsep trace, difference, recontruction, dan iterability. Sedangkan sumber data diambil dari sumber data primer dan sekunder. Adapun teknik yang digunakan dalam penelitian ini adalah heuristik, verifikasi, interpretasi, dan historiografi. Rumusan Pancasila Soekarno terdiri dari lima prinsip sebagai berikut; 1) Pemikiran nasionalisme, Soekarno bermaksud untuk membangkitkan jiwa nasionalisme di kalangan masyarakat Indonesia agar dapat berdiri tegak. 2) Pemikiran internasionalisme, Soekarno bermaksud mengaitkan erat antara pemikiran internasionalisme dengan nasionalisme. 3) Pemikiran demokrasi, dengan demikian -

SETTING HISTORY STRAIGHT? INDONESIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY in the NEW ORDER a Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Center for Inte

SETTING HISTORY STRAIGHT? INDONESIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY IN THE NEW ORDER A thesis presented to the faculty of the Center for International Studies of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Sony Karsono August 2005 This thesis entitled SETTING HISTORY STRAIGHT? INDONESIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY IN THE NEW ORDER by Sony Karsono has been approved for the Department of Southeast Asian Studies and the Center for International Studies by William H. Frederick Associate Professor of History Josep Rota Director of International Studies KARSONO, SONY. M.A. August 2005. International Studies Setting History Straight? Indonesian Historiography in the New Order (274 pp.) Director of Thesis: William H. Frederick This thesis discusses one central problem: What happened to Indonesian historiography in the New Order (1966-98)? To analyze the problem, the author studies the connections between the major themes in his intellectual autobiography and those in the metahistory of the regime. Proceeding in chronological and thematic manner, the thesis comes in three parts. Part One presents the author’s intellectual autobiography, which illustrates how, as a member of the generation of people who grew up in the New Order, he came into contact with history. Part Two examines the genealogy of and the major issues at stake in the post-New Order controversy over the rectification of history. Part Three ends with several concluding observations. First, the historiographical engineering that the New Order committed was not effective. Second, the regime created the tools for people to criticize itself, which shows that it misunderstood its own society. Third, Indonesian contemporary culture is such that people abhor the idea that there is no single truth. -

Perdebatan Tentang Dasar Negara Pada Sidang Badan Penyelidik Usaha-Usaha Persiapan Kemerdekaan (Bpupk) 29 Mei—17 Juli 1945

PERDEBATAN TENTANG DASAR NEGARA PADA SIDANG BADAN PENYELIDIK USAHA-USAHA PERSIAPAN KEMERDEKAAN (BPUPK) 29 MEI—17 JULI 1945 WIDY ROSSANI RAHAYU NPM 0702040354 FAKULTAS ILMU PENGETAHUAN BUDAYA UNIVERSITAS INDONESIA 2008 Perdebatan dasar..., Widy Rossani Rahayu, FIB UI, 2008 1 PERDEBATAN TENTANG DASAR NEGARA PADA SIDANG BADAN PENYELIDIK USAHA-USAHA PERSIAPAN KEMERDEKAAN (BPUPK) 29 MEI–17 JULI 1945 Skripsi diajukan untuk melengkapi persyaratan mencapai gelar Sarjana Humaniora Oleh WIDY ROSSANI RAHAYU NPM 0702040354 Program Studi Ilmu Sejarah FAKULTAS ILMU PENGETAHUAN BUDAYA UNIVERSITAS INDONESIA 2008 Perdebatan dasar..., Widy Rossani Rahayu, FIB UI, 2008 2 KATA PENGANTAR Puji serta syukur tiada terkira penulis panjatkan kepada Allah SWT, yang sungguh hanya karena rahmat dan kasih sayang-Nya, akhirnya penulis dapat menyelesaikan skripsi ini ditengah berbagai kendala yang dihadapi. Ucapan terima kasih dan salam takzim penulis haturkan kepada kedua orang tua, yang telah dengan sabar tetap mendukung putrinya, walaupun putrinya ini sempat melalaikan amanah yang diberikan dalam menyelesaikan masa studinya. Semoga Allah membalas dengan balasan yang jauh lebih baik. Kepada bapak Abdurrakhman M. Hum selaku pembimbing, yang tetap sabar membimbing penulis dan memberikan semangat di saat penulis mendapatkan kendala dalam penulisan. Kepada Ibu Dwi Mulyatari M. A., sebagai pembaca yang telah memberikan banyak saran untuk penulis, sehingga kekurangan-kekurangan dalam penulisan dapat diperbaiki. Kepada Ibu Siswantari M. Hum selaku koordinator skripsi dan bapak Muhammad Iskandar M. Hum selaku ketua Program Studi Sejarah yang juga telah memberikan banyak saran untuk penulisan skripsi ini. Kepada seluruh pengajar Program Studi Sejarah, penulis ucapakan terima kasih untuk bimbingan dan ilmu-ilmu yang telah diberikan. Kepada Bapak RM. A. B. -

Comparison Between the Position of Adopted Children in Islamic Law Inheritance Based on Islamic Law Compilation (KHI) with the Book of Civil Law

Comparison Between The Position Of Adopted Children... (Agil Aladdin) Volume 6 Issue 3, September 2019 Comparison Between The Position Of Adopted Children In Islamic Law Inheritance Based On Islamic Law Compilation (KHI) With The Book Of Civil Law Agil Aladdin1 and Akhmad Khisni2 Abstract. This research aims to knowing position adopted child in Islamic Law Compilation with the Book of Civil Law; and Similarities and Differences position adopted children in inheritance of Islamic Law Compilation with the Book of Civil Law; This research method using normative juridical research with comparative approach (comparative). The results were obtained conclusions from Islamic Law Compilation in terms of inheritance, uninterrupted lineage adopted children with biological parents, who turned just the responsibility of the biological parents to the adoptive parents. The adopted child does not become heir of adopted parents. In Gazette No. 129 Of 1917. In Article 5 through Article 15. The position adopted child found in Article 12 to equate a child with a legitimate child of the marriage of the lift. According to the Civil Law for the adopted child the same as for biological children. While in KHI adopted children get as much as 1/3 of the estate left by his adoptive parents (Article 209 KHI) exception has been assigned the consent of all the heirs. Keywords: Heritage; Adopted; Testament. 1. Introduction In a marriage between husband and wife are expected to get a good descent and is a beacon of hope for both parents. The presence of children is a form of continuity of a family and the offspring as an investment in the future, but a marriage will be is not yet complete when the couple no children.