A Study of Ukiyo-E's Place in the Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Western Literature in Japanese Film (1910-1938) Alex Pinar

ADVERTIMENT. Lʼaccés als continguts dʼaquesta tesi doctoral i la seva utilització ha de respectar els drets de la persona autora. Pot ser utilitzada per a consulta o estudi personal, així com en activitats o materials dʼinvestigació i docència en els termes establerts a lʼart. 32 del Text Refós de la Llei de Propietat Intel·lectual (RDL 1/1996). Per altres utilitzacions es requereix lʼautorització prèvia i expressa de la persona autora. En qualsevol cas, en la utilització dels seus continguts caldrà indicar de forma clara el nom i cognoms de la persona autora i el títol de la tesi doctoral. No sʼautoritza la seva reproducció o altres formes dʼexplotació efectuades amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva comunicació pública des dʼun lloc aliè al servei TDX. Tampoc sʼautoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant als continguts de la tesi com als seus resums i índexs. ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis doctoral y su utilización debe respetar los derechos de la persona autora. Puede ser utilizada para consulta o estudio personal, así como en actividades o materiales de investigación y docencia en los términos establecidos en el art. 32 del Texto Refundido de la Ley de Propiedad Intelectual (RDL 1/1996). Para otros usos se requiere la autorización previa y expresa de la persona autora. En cualquier caso, en la utilización de sus contenidos se deberá indicar de forma clara el nombre y apellidos de la persona autora y el título de la tesis doctoral. -

Meta-Con-2014-FINAL.Pdf

Convention Operations and Answers General Rules Weapon and Large Prop Rules Our convention has a number of rules, policies, and regulations All weapons and large props must be inspected and approved by our that help make the convention run smoothly and be as fun as operations or security staff at the convention. We will then “peace mark” possible for everyone. We encourage you to read our rules to un- them, by affixing a ribbon or mark that indicates we have checked them, and, if necessary “peace bond” them by using ribbon or ties to keep derstand what is expected to help make the best, most success- your weapon from being drawn or used (for example, by someone who ful, and most fun weekend possible. In addition to these general doesn’t know the rules and sneaks up behind you and grabs it). Attend- conduct policies, we also have rules and guidelines for cosplay, ees must realize that it is a privilege to bring large props and weapons press, exhibitors, and others. Violations of these rules and respon- to the convention, and everyone must take great care to be careful not sibilities can result in loss of privileges, up to and including ejec- to damage things, whack people, or otherwise do anything that seems tion without refund, legal action, or involvement of the authorities. dangerous. We allow certain specific prop weapons and large prop items, but anything not listed below is not allowed. Please understand that due Rule Number One: Do not do anything that could make the to crowding, space, or safety issues, we may have to change the rules mid-convention at any time. -

Vaitoskirjascientific MASCULINITY and NATIONAL IMAGES IN

Faculty of Arts University of Helsinki, Finland SCIENTIFIC MASCULINITY AND NATIONAL IMAGES IN JAPANESE SPECULATIVE CINEMA Leena Eerolainen DOCTORAL DISSERTATION To be presented for public discussion with the permission of the Faculty of Arts of the University of Helsinki, in Room 230, Aurora Building, on the 20th of August, 2020 at 14 o’clock. Helsinki 2020 Supervisors Henry Bacon, University of Helsinki, Finland Bart Gaens, University of Helsinki, Finland Pre-examiners Dolores Martinez, SOAS, University of London, UK Rikke Schubart, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark Opponent Dolores Martinez, SOAS, University of London, UK Custos Henry Bacon, University of Helsinki, Finland Copyright © 2020 Leena Eerolainen ISBN 978-951-51-6273-1 (paperback) ISBN 978-951-51-6274-8 (PDF) Helsinki: Unigrafia, 2020 The Faculty of Arts uses the Urkund system (plagiarism recognition) to examine all doctoral dissertations. ABSTRACT Science and technology have been paramount features of any modernized nation. In Japan they played an important role in the modernization and militarization of the nation, as well as its democratization and subsequent economic growth. Science and technology highlight the promises of a better tomorrow and future utopia, but their application can also present ethical issues. In fiction, they have historically played a significant role. Fictions of science continue to exert power via important multimedia platforms for considerations of the role of science and technology in our world. And, because of their importance for the development, ideologies and policies of any nation, these considerations can be correlated with the deliberation of the role of a nation in the world, including its internal and external images and imaginings. -

Lone Wolf and Cub Volume 24: in These Small Hands Pdf, Epub, Ebook

LONE WOLF AND CUB VOLUME 24: IN THESE SMALL HANDS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Kazuo Koike,Goseki Kojima | 320 pages | 10 Sep 2002 | Dark Horse Comics,U.S. | 9781569715963 | English | Milwaukie, United States Lone Wolf and Cub Volume 24: In These Small Hands PDF Book The Yagyu letter plot has also advanced here. Jan 28, Ill D rated it it was amazing Recommends it for: Japanophiles. About the Author Kazuo Koike is a prolific Japanese manga writer, novelist, and entrepreneur. Randy Stradley. Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Ben Wong rated it really liked it Feb 12, Drug and Drop Volume 2. A samurai epic of staggering proportions, the acclaimed Lone Wolf and Cub begins its second Please try again later. Publisher: Dark Horse Comics. So, in these final days, a ronin and his young boy will visit the grave of their murdered wife and mother. Koike, along with artist Goseki Kojima, made the manga Kozure Okami Lone Wolf and Cub , and Koike also contributed to the scripts for the s film adaptations of the series, which starred famous Japanese actor Tomisaburo Wakayama. When you buy a book, we donate a book. Eventually, the two opposing master swordsmen dry off and go head to head in a sword fight of a thousand stances and couple of days length. Dark Horse respects your privacy. It just might be the last Spring the two will share, like the many petals falling from branches. Start your review of Lone Wolf and Cub, Vol. By using digital. Yoshiki Tanaka. For a better shopping experience, please upgrade now. -

Manga Book Club Handbook

MANGA BOOK CLUB HANDBOOK Starting and making the most of book clubs for manga! STAFF COMIC Director’sBOOK LEGAL Note Charles Brownstein, Executive Director DEFENSE FUND Alex Cox, Deputy Director Everything is changing in 2016, yet the familiar challenges of the past continueBetsy to Gomez, Editorial Director reverberate with great force. This isn’t just true in the broader world, but in comics,Maren Williams, Contributing Editor Comic Book Legal Defense Fund is a non-profit organization Caitlin McCabe, Contributing Editor too. While the boundaries defining representation and content in free expression are protectingexpanding, wethe continue freedom to see to biasedread comics!or outmoded Our viewpoints work protects stifling those advances.Robert Corn-Revere, Legal Counsel readers, creators, librarians, retailers, publishers, and educa- STAFF As you’ll see in this issue of CBLDF Defender, we are working on both ends of the Charles Brownstein, Executive Director torsspectrum who byface providing the threat vital educationof censorship. about the We people monitor whose worklegislation expanded free exBOARD- Alex OF Cox, DIRECTORS Deputy Director pression while simultaneously fighting all attempts to censor creative work in comics.Larry Marder,Betsy Gomez, President Editorial Director and challenge laws that would limit the First Amendment. Maren Williams, Contributing Editor In this issue, we work the former end of the spectrum with a pair of articles spotlightMilton- Griepp, Vice President We create resources that promote understanding of com- Jeff Abraham,Caitlin McCabe,Treasurer Contributing Editor ing the pioneers who advanced diverse content. On page 10, “Profiles in Black Cartoon- Dale Cendali,Robert SecretaryCorn-Revere, Legal Counsel icsing” and introduces the rights you toour some community of the cartoonists is guaranteed. -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

I TEAM JAPAN: THEMES of 'JAPANESENESS' in MASS MEDIA

i TEAM JAPAN: THEMES OF ‘JAPANESENESS’ IN MASS MEDIA SPORTS NARRATIVES A Dissertation submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Michael Plugh July 2015 Examining Committee Members: Fabienne Darling-Wolf, Advisory Chair, Media and Communication Doctoral Program Nancy Morris, Media and Communication Doctoral Program John Campbell, Media and Communication Doctoral Program Lance Strate, External Member, Fordham University ii © Copyright 2015 by MichaelPlugh All Rights Reserved iii Abstract This dissertation concerns the reproduction and negotiation of Japanese national identity at the intersection between sports, media, and globalization. The research includes the analysis of newspaper coverage of the most significant sporting events in recent Japanese history, including the 2014 Koshien National High School Baseball Championships, the awarding of the People’s Honor Award, the 2011 FIFA Women’s World Cup, wrestler Hakuho’s record breaking victories in the sumo ring, and the bidding process for the 2020 Olympic Games. 2054 Japanese language articles were examined by thematic analysis in order to identify the extent to which established themes of “Japaneseness” were reproduced or renegotiated in the coverage. The research contributes to a broader understanding of national identity negotiation by illustrating the manner in which established symbolic boundaries are reproduced in service of the nation, particularly via mass media. Furthermore, the manner in which change is negotiated through processes of assimilation and rejection was considered through the lens of hybridity theory. iv To my wife, Ari, and my children, Hiroto and Mia. Your love sustained me throughout this process. -

Univerzita Karlova V Praze Filozofická Fakulta

Univerzita Karlova v Praze Filozofická fakulta Ústav Dálného východu Bakalářská práce Kateřina Danišová Vztah umění a vytváření japonské národní identity v moderním období The Relation of Art and Japanese National Identity in the Modern Era Praha, 2011 vedoucí práce: Mgr. David Labus, Ph.D. Poděkování Tímto bych chtěla poděkovat Mgr. Davidu Labusovi, Ph.D., za vedení práce, užitečné rady a připomínky. Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalářskou práci vypracovala samostatně, že jsem řádně citovala všechny použité prameny a literaturu a že práce nebyla využita v rámci jiného vysokoškolského studia či k získání jiného nebo stejného titulu. V Praze dne 9.7.2011 podpis Anotace Bakalářská práce se zaměřuje na představení nových západních uměleckých technik, které se v Japonsku rozšířily během období Meidži, dále na způsob jejich interakce s tradičními žánry a formami. Soustřeďuje se na role jedinců, zejména Ernesta Fenollosy a Okakury Tenšina, spolků a institucí při vytváření vědomí národní identity a také na roli, kterou kultura zastala ve vznikající moderní ideologii. Annotation This bachelor dissertation concentrates on the introduction of the new artistic techniques, which spread out in Japan during the Meiji period, and on their interaction with the traditional genres and forms. It examines the role of individuals, particularly Ernest Fenollosa and Okakura Tenshin, societies and institutions in the process of creating a national identity. It also deals with the part of the culture in the developing of a modern ideology. Klíčová slova Japonsko, japonské umění, umění v období Meidži, národní identita, interakce tradičního a moderního umění, moderní japonské umění, Okakura, Fenollosa, Conder, jóga, nihonga. Keywords Japan, japanese art, Meiji period art, national identity, traditional and modern art interaction, japanese modern art, Okakura, Fenollosa, Conder, jōga, nihonga. -

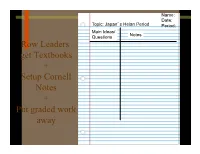

7.5 Heian Notes

Name: Date: Topic: Japan’s Heian Period Period: Main Ideas/ Questions Notes Row Leaders get Textbooks + Setup Cornell Notes + Put graded work away A New Capital • In 794, the Emperor Kammu built a new capital city for Japan, called Heian-Kyo. • Today, it is called Kyoto. • The Heian Period is called Japan’s “Golden Age” Essential Question: What does “Golden Age” mean? Inside the city • Wealthy families lived in mansions surrounded by gardens. A Powerful Family • The Fujiwara family controlled Japan for over 300 years. • They had more power than the emperor and made important decisions for Japan. Beauty and Fashion • Beauty was important in Heian society. • Men and women blackened their teeth. • Women plucked their eyebrows and painted them higher on their foreheads. Beauty and Fashion • Heian women wore as many as 12 silk robes at a time. • Long hair was also considered beautiful. Entertainment • The aristocracy had time for diversions such as go (a board game), kemari (keep the ball in play) and bugaku theater. Art • Yamato-e was a style of Japanese art that reflected nature from the Japanese religion of Shinto. Writing and Literature • The Tale of Genji was written by Murasaki Shikibu, a woman, and is considered the world’s first novel. Japanese Origami Book Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. . -

Manga) Market in the US

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Papers in Economics The Diffusion of Foreign Cultural Products: The Case Analysis of Japanese Comics (Manga) Market in the US Takeshi Matsui Working Paper #37, Spring 2009 The Diffusion of Foreign Cultural Products: The Case Analysis of Japanese Comics (Manga) Market in the US * Takeshi Matsui Graduate School Department of Sociology of Commerce and Management Princeton University Hitotsubashi University Princeton, NJ, US 08544 Tokyo, Japan 186-8601 [ Word Count: 8,230] January 2009 * I would like to thank Paul DiMaggio, Russell Belk, Jason Thompson, Stephanie Schacht, and Richard Cohn for helpful feedback and encouragement. This research project is supported by Abe Fellowship (SSRC/Japan Foundation), Josuikai (Alumni Society of Hitotsubashi University), and Japan Productivity Center for Socio-economic Development. Please address correspondence to Takeshi Matsui, Department of Sociology, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544. E-mail: [email protected]. The Diffusion of Foreign Cultural Products: The Case Analysis of Japanese Comics (Manga) Market in the US Takeshi Matsui Hitotsubashi University/Princeton University Abstract This paper outlines the historical development of the US manga (Japanese comics) industry from the 1980s through the present in order to address the question why foreign cultural products become popular in offshore markets in spite of cultural difference. This paper focuses on local publishers as “gatekeepers” in the introduction of foreign culture. Using complete data on manga titles published in the US market from 1980 to 2006 (n=1,058), this paper shows what kinds of manga have been translated, published, and distributed for over twenty years and how the competition between the two market leaders, Viz and Tokyopop, created the rapid market growth. -

I. Early Days Through 1960S A. Tezuka I. Series 1. Sunday A

I. Early days through 1960s a. Tezuka i. Series 1. Sunday a. Dr. Thrill (1959) b. Zero Man (1959) c. Captain Ken (1960-61) d. Shiroi Pilot (1961-62) e. Brave Dan (1962) f. Akuma no Oto (1963) g. The Amazing 3 (1965-66) h. The Vampires (1966-67) i. Dororo (1967-68) 2. Magazine a. W3 / The Amazing 3 (1965) i. Only six chapters ii. Assistants 1. Shotaro Ishinomori a. Sunday i. Tonkatsu-chan (1959) ii. Dynamic 3 (1959) iii. Kakedaze Dash (1960) iv. Sabu to Ichi Torimono Hikae (1966-68 / 68-72) v. Blue Zone (1968) vi. Yami no Kaze (1969) b. Magazine i. Cyborg 009 (1966, Shotaro Ishinomori) 1. 2nd series 2. Fujiko Fujio a. Penname of duo i. Hiroshi Fujimoto (Fujiko F. Fujio) ii. Moto Abiko (Fujiko Fujio A) b. Series i. Fujiko F. Fujio 1. Paaman (1967) 2. 21-emon (1968-69) 3. Ume-boshi no Denka (1969) ii. Fujiko Fujio A 1. Ninja Hattori-kun (1964-68) iii. Duo 1. Obake no Q-taro (1964-66) 3. Fujio Akatsuka a. Osomatsu-kun (1962-69) [Sunday] b. Mou Retsu Atarou (1967-70) [Sunday] c. Tensai Bakabon (1969-70) [Magazine] d. Akatsuka Gag Shotaiseki (1969-70) [Jump] b. Magazine i. Tetsuya Chiba 1. Chikai no Makyu (1961-62, Kazuya Fukumoto [story] / Chiba [art]) 2. Ashita no Joe (1968-72, Ikki Kajiwara [story] / Chiba [art]) ii. Former rental magazine artists 1. Sanpei Shirato, best known for Legend of Kamui 2. Takao Saito, best known for Golgo 13 3. Shigeru Mizuki a. GeGeGe no Kitaro (1959) c. Other notable mangaka i. -

The Drifting Classroom: Volume 2 Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE DRIFTING CLASSROOM: VOLUME 2 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Kazuo Umezu | 188 pages | 10 Oct 2006 | Viz Media | 9781421507231 | English | San Francisco, CA, United States The Drifting Classroom: Volume 2 PDF Book Still as good as ever. When he returns to the classroom, they team up to take down the delivery man when he shows up, hand out the food to everyone, but one of the teachers has gone mad and killed all of the other teachers. Finally, it is the mission of IJER to help readers to learn about key issues in school reform from movers and shakers who help to study and shape the power base directing educational reform in the U. Inazuman Dororon Enma-kun. Log in. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. I want! Jump to: Manga Series. Friend Reviews. The series follows a school that is mysteriously transported through time to a post-apocalyptic future. We at least find out how the school vanished, and holy wow. I did like, well at least at first, that they took a car to go an excursion. Honestly, this series is a wild ride. As the hopelessness of their situation becomes clear, many of the adults descend into insanity. You may block cookies via standard web-browser settings, but this site may not function correctly without cookies. This is a simple and durable all-purpose daily notebook. I think Lord of the Flies did it first, but hey whatever. In a world where cursed spirits feed on unsuspecting The high-pitched battle is on between powerful angels, sexy demons and innocent humans to dominate Other The Drifting Classroom volumes See all.