Travel in London Report 13

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The London Congestion Charge

Journal of Economic Perspectives—Volume 20, Number 4—Fall 2006—Pages 157–176 The London Congestion Charge Jonathan Leape y the 1990s, the average speed of trips across London was below that at the beginning of the twentieth century—before the car was introduced (New- B bery, 1990, p. 35). Traffic speeds in central London had fallen more than 20 percent since the 1960s, from an average 12.7 mph for the morning peak period in 1968 (and a high of 14.2 mph in 1975) to 10 mph in 1998. Even in the larger area of inner London, drivers in 1998 spent almost 30 percent of their time stationary during peak periods and more than half their time traveling at speeds of less than 10 mph (Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions, 1998). By 2002, the all-day average travel speed in central London was just 8.6 mph (14.3 km/hour), compared to an uncongested (night-time or “free flow”) average speed of around 20 mph (32 km/hour). Congestion, measured in terms of minutes of delay per mile compared to uncongested conditions, averaged 3.7 minutes/mile (2.3 min/km) (Transport for London, 2003a, p. 11). With more than one million people entering central London between 7:00 and 10:00 a.m. on an average workday, and more than one-quarter of those by road, the cost of congestion was clearly considerable. Public concern over levels of traffic congestion was high. An independent survey in 1999 identified public transport and congestion as the two most “impor- tant problems requiring action”—selected by 46 and 33 percent of London resi- dents, respectively, compared to 20 percent for crime or law and order. -

Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--History History 2016 Minding the Gap: Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945 Danielle K. Dodson University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: http://dx.doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2016.339 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Dodson, Danielle K., "Minding the Gap: Uncovering the Underground's Role in the Formation of Modern London, 1855-1945" (2016). Theses and Dissertations--History. 40. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/history_etds/40 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the History at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--History by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Congestion Charges for Urban Transport

GOOD PRACTICES IN CITY ENERGY EFFICIENCY London, United Kingdom – Congestion Charges for Urban Transport Energy Sector Management Assistance Program (ESMAP) reports are published to communicate the results of ESMAP’s work to the development community. This document has not been prepared in accordance with the procedures appropriate to formal documents. Some sources cited in this paper may be informal documents that are not readily available. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this report are entirely those of the author(s) and should not be attributed in any manner to the World Bank, or its affiliated organizations, or to members of its board of executive directors for the countries they represent, or to ESMAP. London Transportation Case Study August 2011 Project title London Congestion Charges for Urban Transport Sector Urban Transport Type of project Congestion Charges City and country London, United Kingdom City population 8.59 million (in 2008) Capital Cost US$242.8 million (Phase 1, 2002/3) US$189.5 million (Phase 2, 2006/7)1 Annual % of energy reduction 3% (44-48 million liters annually) Project status Ongoing; Phase 1 completed 2003, Phase 2 completed 2007 Project Summary In February 2003, London, the capital city of the United Kingdom (U.K.), introduced a daily congestion fee for vehicles travelling in the city’s central district during weekdays. This fee was meant to ease traffic congestion, improve travel time and reliability, and make central London more attractive to businesses and visitors. According to analysis by the City, the program has largely met its objectives. After four years of operation, traffic entering the charge zone was reduced by 21 percent; congestion, measured as a travel rate (minutes per kilometer), was 8 percent lower; and annual fuel consumption fell by approximately 44-48 million liters or about 3 percent. -

Traffic Accidents and the London Congestion Charge

Economics Working Paper Series 2014/015 Traffic Accidents and the London Congestion Charge Colin P. Green, John. S. Heywood and Maria Navarro The Department of Economics Lancaster University Management School Lancaster LA1 4YX UK © Authors All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission, provided that full acknowledgement is given. LUMS home page: http://www.lums.lancs.ac.uk/ Traffic Accidents and the London Congestion Charge Colin P. Green1, John. S. Heywood2,1 and Maria Navarro1 1Lancaster University 2 University of Wisconsin - Milwaukee Abstract In a rare effort to internalize congestion costs, London recently instituted charges for traveling by car to the central city during peak hours. Although the theoretical influence on the number and severity of traffic accidents is ambiguous, we show that the policy generated a substantial reduction in both accidents and fatalities in the charged area and hours. At the same time, the spatial, temporal and vehicle specific nature of the charge may cause unintended substitutions as traffic and accidents shift to other proximate areas, times and to uncharged vehicles. We demonstrate that, to the contrary, the congestion charge reduced accidents and fatalities in adjacent areas, times and for uncharged vehicles. These results are consistent with the government's objective to use the congestion charge to more broadly promote public transport and change driving habits. JEL Codes: I18, R48, H27 Keywords: Traffic Congestion; Pricing; Vehicle Accidents The authors thank the Melvin Lurie Memorial Fund at UWM which allowed Heywood and Navarro to work together in the fall of 2013. -

Operators Route Contracts

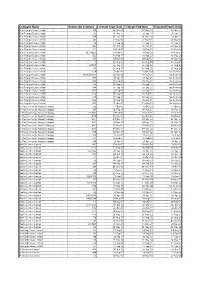

Company Name Routes On Contract Contract Start Date Contract End Date Extended Expiry Date Blue Triangle Buses Limited 300 06-Mar-10 07-Dec-18 03-Mar-17 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 193 01-Oct-11 28-Sep-18 28-Sep-18 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 364 01-Nov-14 01-Nov-19 29-Oct-21 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 147 07-May-16 07-May-21 05-May-23 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 376 17-Sep-16 17-Sep-21 15-Sep-23 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 346 01-Oct-16 01-Oct-21 29-Sep-23 Blue Triangle Buses Limited EL3 18-Feb-17 18-Feb-22 16-Feb-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited EL1/NEL1 18-Feb-17 18-Feb-22 16-Feb-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited EL2 18-Feb-17 18-Feb-22 16-Feb-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 101 04-Mar-17 04-Mar-22 01-Mar-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 5 26-Aug-17 26-Aug-22 23-Aug-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 15/N15 26-Aug-17 26-Aug-22 23-Aug-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 115 26-Aug-17 26-Aug-22 23-Aug-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 674 17-Oct-15 16-Oct-20 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 649/650/651 02-Jan-16 01-Jan-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 687 30-Apr-16 30-Apr-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 608 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 646 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 648 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 652 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 656 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 679 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 686 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote -

Understanding and Managing Congestion

Understanding and Managing Congestion For Transport for London On behalf of Greater London Authority Final Version 1-0 November 2017 Understanding and Managing Congestion Final Version 1-0 November 2017 Produced by: For: Transport for London On behalf of: Greater London Authority Contact: Jim Bradley Integrated Transport Planning Ltd. 6 Hay’s Lane London Bridge London SE1 2HB UNITED KINGDOM 0203 300 1810 [email protected] www.itpworld.net Understanding and Managing Congestion Project Information Sheet Client TfL Project Code 2398 Project Name Understanding and Managing Congestion Project Director Jim Bradley Project Manager Robin Kaenzig Quality Manager Jim Bradley Additional Team Members Jon Harris, Juan Sanclemente, Matt Cottam, Ruby Stringer, Georgia Corr, David Hicks File Location F:\2300-2399\2398 TfL Understanding and Managing Congestion\Technical\Final Report Document Control Sheet Ver. File Name Description Prep. Rev. App. Date V1-0 F:\ Understanding and Final Report RK JB JB 14/11/2017 Managing Congestion Final Report 141117 v1-0 Notice This report has been prepared for TfL and GLA in accordance with the terms and conditions of appointment. Integrated Transport Planning Ltd cannot accept any responsibility for any use of or reliance on the contents of this report by any third party. Understanding and Managing Congestion Acknowledgements An independent panel of experts was invited to provide advice and expertise to inform this study. The panel met four times over the course of the study’s development and comprised: • Dr Rachel Aldred; • Mr Terence Bendixson; • Dr Adrian Davis; and • Dr Lynn Sloman. We would like to extend our sincere thanks to all the panel members for their time and expertise. -

Transport with So Many Ways to Get to and Around London, Doing Business Here Has Never Been Easier

Transport With so many ways to get to and around London, doing business here has never been easier First Capital Connect runs up to four trains an hour to Blackfriars/London Bridge. Fares from £8.90 single; journey time 35 mins. firstcapitalconnect.co.uk To London by coach There is an hourly coach service to Victoria Coach Station run by National Express Airport. Fares from £7.30 single; journey time 1 hour 20 mins. nationalexpress.com London Heathrow Airport T: +44 (0)844 335 1801 baa.com To London by Tube The Piccadilly line connects all five terminals with central London. Fares from £4 single (from £2.20 with an Oyster card); journey time about an hour. tfl.gov.uk/tube To London by rail The Heathrow Express runs four non- Greater London & airport locations stop trains an hour to and from London Paddington station. Fares from £16.50 single; journey time 15-20 mins. Transport for London (TfL) Travelcards are not valid This section details the various types Getting here on this service. of transport available in London, providing heathrowexpress.com information on how to get to the city On arrival from the airports, and how to get around Heathrow Connect runs between once in town. There are also listings for London City Airport Heathrow and Paddington via five stations transport companies, whether travelling T: +44 (0)20 7646 0088 in west London. Fares from £7.40 single. by road, rail, river, or even by bike or on londoncityairport.com Trains run every 30 mins; journey time foot. See the Transport & Sightseeing around 25 mins. -

Passenger Focus' Response to C2c's Proposed Franchise Extension July

Passenger Focus’ response to c2c’s proposed franchise extension July 2008 Passenger Focus – who we are and what we do Passenger Focus is the independent national rail consumer watchdog. It is an executive non- departmental public body sponsored by the Department for Transport. Our mission is to get the best deal for Britain's rail passengers. We have two main aims: to influence both long and short term decisions and issues that affect passengers and to help passengers through advice, advocacy and empowerment. With a strong emphasis on evidence-based campaigning and research, we ensure that we know what is happening on the ground. We use our knowledge to influence decisions on behalf of rail passengers and we work with the rail industry, other passenger groups and Government to secure journey improvements. Our vision is to ensure that the rail industry and Government are always ‘putting rail passengers first’ This will be achieved through our mission of ‘getting the best deal for passengers’ 1 Contents 1. Introduction 3 2. Executive summary 3 3. Response to DfT consultation document 4 4. Appendix A: summary of consultation responses 10 5. Contact details 12 2 1. Introduction Passenger Focus welcomes the opportunity to comment on the Department for Transport’s (DfT) consultation on the proposal to extend c2c’s franchise by two years. Although the consultation process has not been formally set out we were aware of informal discussions for an extension since last year. We view the extension proposal as a very good opportunity for the c2c franchise to be revitalised with a fresh mandate to develop and improve operational performance as well as customer services. -

The Go-Ahead Group Plc Annual Report and Accounts 2019 1 Stable Cash Generative

Annual Report and Accounts for the year ended 29 June 2019 Taking care of every journey Taking care of every journey Regional bus Regional bus market share (%) We run fully owned commercial bus businesses through our eight bus operations in the UK. Our 8,550 people and 3,055 buses provide Stagecoach: 26% excellent services for our customers in towns and cities on the south FirstGroup: 21% coast of England, in north east England, East Yorkshire and East Anglia Arriva: 14% as well as in vibrant cities like Brighton, Oxford and Manchester. Go-Ahead’s bus customers are the most satisfied in the UK; recently Go-Ahead: 11% achieving our highest customer satisfaction score of 92%. One of our National Express: 7% key strengths in this market is our devolved operating model through Others: 21% which our experienced management teams deliver customer focused strategies in their local areas. We are proud of the role we play in improving the health and wellbeing of our communities through reducing carbon 2621+14+11+7+21L emissions with cleaner buses and taking cars off the road. London & International bus London bus market share (%) In London, we operate tendered bus contracts for Transport for London (TfL), running around 157 routes out of 16 depots. TfL specify the routes Go-Ahead: 23% and service frequency with the Mayor of London setting fares. Contracts Metroline: 18% are tendered for five years with a possible two year extension, based on Arriva: 18% performance against punctuality targets. In addition to earning revenue Stagecoach: 13% for the mileage we operate, we have the opportunity to earn Quality Incentive Contract bonuses if we meet these targets. -

Making Rail Accessible: Helping Older and Disabled Passengers

Making Rail Accessible: Helping Older and Disabled Passengers Valid from May 2016 Contents Page Introduction 2 About our services Policy Summary 4 Passenger Assistance 5-6 Turn Up and Go 7 Ramps Journeys with multiple operators Changes to facilities 8 Alternative accessible transport 9 Passenger Information Tickets and fares 10 At our stations 11-15 Station Entrance Aural and visual information Information points and displays Ticket machines Ticket Gates Luggage Left Luggage Ramps for boarding and alighting trains Facilities provided by third parties Aural and visual information On our trains 16-17 Seats on our trains Wheelchairs and Scooters Information about our trains Making Connections 18-19 Connection with other train services Intermodal connections Disruption to facilities and services Contact us 20 Station accessibility and key features 21-25 Route map 26 Introduction Welcome to Making rail accessible: helping older and disabled passengers. This guide provides information to help older or disabled passengers plan their journey with c2c, and makes up one half of our Disabled People’s Protection Policy (DPPP). The other half is called Making rail accessible: guide to policies and practices, which sets out c2c’s policies and strategies relating to accessibility. You can find Making rail accessible: helping older and disabled passengers in leaflet racks at all c2c stations, at the ticket office at other stations where c2c trains call, and on our website (in both PDF and Word formats). You can request a copy of either document from our Customer Relations team, who will send one within seven working days. About our services c2c operate passenger trains between London Fenchurch Street and Shoeburyness, calling at intermediate stations via Basildon, Tilbury Town and Grays. -

A Rail Manifesto for London

A Rail Manifesto for London The new covered walkway linking Hackney Central and Hackney Downs stations creates an interchange which provides a better connection and more journey opportunities March 2016 A Rail Manifesto for London Railfuture1 seeks to inform and influence the development of transport policies and practices nationally and locally. We offer candidates for the 2016 London Mayoral and Assembly elections this manifesto2, which represents a distillation of the electorate’s aspirations for a developing railway for London, for delivery during the next four years or to be prepared for delivery during the following period of office. Executive Summary Recognising the importance of all rail-based transport to the economy of London and to its residents, commuters and visitors alike, Railfuture wishes to see holistic and coherent rail services across all of London, integrated with all other public transport, with common fares and conditions. Achieving this is covered by the following 10 policy themes: 1. Services in London the Mayor should take over. The 2007 transfer of some National Rail services to TfL has been a huge success, transforming some of the worst services in London into some of the best performing. Railfuture believes it is right that the Mayor should take over responsibility for more rail services in London, either by transferring service operation to TfL or by TfL specifying service levels to the operator, and that this must benefit all of London. 2. Improved Services. Frequencies play an important role in the success of metro and suburban train services. We believe that the Mayor should set out the minimum standards of service levels across London seven days per week for all rail services. -

A Practical Guide to London's Transport Services for Disabled and Older

Get moving A practical guide to London’s transport services for disabled and older people 2 Get moving Information to help you make the most of London’s transport services Get moving Information to help you make the most of London’s transport services 3 Contents 4 About us and our services 33 Capital Call 34 Freedom Pass 6 London-wide transport 37 Blue Badge 7 Docklands Light Railway (DLR) 38 Non-emergency hospital transport 7 London Underground 11 London buses 39 National Express Coachcard 12 Riverboats 42 Community transport 12 Train services 43 Service providers’ contact details 16 Tramlink 46 Shopmobility information 17 Travel training 18 Personal transport 48 London Airports 19 Motoring 52 The Equality Act and transport Mobility scooters 21 55 Hate crime and anti-social behaviour 24 Cycling 56 Making a complaint 26 Door to door and concessionary travel 27 Railcards 58 London Borough Council contact details 29 Dial-a-Ride 60 Useful numbers 31 Taxicard 4 Get moving Information to help you make the most of London’s transport services About us and our services Get moving Information to help you make the most of London’s transport services 5 Transport for All passionately believes that all disabled We can also act as advocates on your behalf and and older people have the right to travel with freedom take up complaints when services let you down. and independence, and to live our lives to the full. Tel: 020 7737 2339 We specialise in providing the expert transport advice, Text: 07793 879643 information and advocacy to help you do just that.