The Making of the White Middle-Class Radical: a Discourse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Latin American Agenda 2016

World Latin American Agenda 2016 In its category, the Latin American book most widely distributed inside and outside the Americas each year. A sign of continental and global communion among individuals and communities excited by and committed to the Great Causes of the Patria Grande. An Agenda that expresses the hope of the world’s poor from a Latin American perspective. A manual for creating a different kind of globalization. A collection of the historical memories of militancy. An anthology of solidarity and creativity. A pedagogical tool for popular education, communication and social action. From the Great Homeland to the Greater Homeland. Our cover image by Maximino CEREZO BARREDO. See all our history, 25 years long, through our covers, at: latinoamericana.org/digital /desde1992.jpg and through the PDF files, at: latinoamericana.org/digital This year we remind you... We put the accent on vision, on attitude, on awareness, on education... Obviously, we aim at practice. However our “charisma” is to provoke the transformations of awareness necessary so that radically new practices might arise from another systemic vision and not just reforms or patches. We want to ally ourselves with all those who search for that transformation of conscience. We are at its service. This Agenda wants to be, as always and even more than at other times, a box of materials and tools for popular education. latinoamericana.org/2016/info is the web site we have set up on the network in order to offer and circulate more material, ideas and pedagogical resources than can economically be accommo- dated in this paper version. -

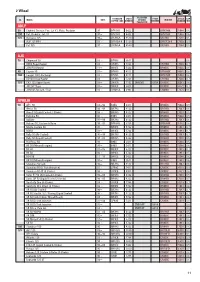

Fitment Chart (Pdf)

2 Wheel PLATINUM CC MODEL DATE STANDARD STOCK OR GOLD STOCK IRIDIUM STOCK GAP COPPER CORE NUMBER PALLADIUM NUMBER NUMBER MM ADLY 50 Citybird, Crosser, Fox, Jet X1, Pista, Predator 97 BPR7HS 6422 BPR7HIX 5944 0.6 100 Cat, Predator, Jet, X1 97 BPR7HS 6422 BPR7HIX 5944 0.6 125 Activator 125 99 CR7HSA 4549 CR7HIX 7544 0.5 AJP 125 PR4 03 DPR7EA-9 5129 DPR7EIX-9 7803 0.9 Cat 125 97 CR7HSA 4549 CR7HIX 7544 0.5 AJS 50 Chipmunk 50 03 BP4HS 3611 0.6 DD50 Regal Raptor 03 CR7HS 7223 CR7HIX 7544 0.7 JSM 50 Motard 11 BR8ES 5422 BR8EIX 5044 0.6 80 Coyote 80 03 BP6HS 4511 BPR6HIX 4085 0.6 100 Cougar 100 (Jincheng) 03 BP7HS 5111 BPR7HIX 5944 0.6 DD100 Regal Raptor 03 CR7HS 7223 CR7HIX 7544 0.7 125 CR3-125 Super Sports 08 DR8EA 7162 DR8EVX 6354 DR8EIX 6681 0.6 JS125Y Tiger 03 DR8ES 5423 DR9EIX 4772 0.7 JSM125 Motard / Trail 10 CR6HSA 2983 CR6HIX 7274 0.6 APRILIA 50 AF1 50 8892 B8ES 2411 BR8EIX 5044 0.5 Amico 50 9294 BR7HS 4122 BR7HIX 7067 0.6 Area 51 (Liquid Cooled 2-Stroke) 98 BR8HS 4322 BR8HIX 7001 0.5 Extrema 50 93 B8ES 2411 BR8EIX 5044 0.5 Gulliver 9799 BR7HS 4122 BR7HIX 7067 0.6 Habana 50, Custom & Retro 9905 BPR8HS 3725 BPR8HIX 6742 0.6 Mojito Custom 50 05 BR9ES 5722 BR9EIX 3981 0.7 MX50 03 BR9ES 5722 BR9EIX 3981 0.7 Rally 50 (Air Cooled) 9599 BR7HS 4122 BR7HIX 7067 0.7 Rally 50 (Liquid Cooled) 9703 BR8HS 4322 BR8HIX 7001 0.5 Red Rose 50 93 B8ES 2411 BR8EIX 5044 0.5 RS 50 (Minarelli engine) 93 B8ES 2411 BR8EIX 5044 0.6 RS 50 0105 BR9ES 5722 BR9EIX 3981 0.7 RS 50 06 BR9ES 5722 BR9EIX 3981 0.5 RS4 50 1113 BR8ES 5422 BR8EIX 5044 0.6 ‡ Early Ducati Testastretta bikes (749, 998, 999 models) can have very little clearance between the plug hex and the RX 50 (Minarelli engine) 97 B9ES 2611 BR9EIX 3981 0.6 cylinder head that may require a thin walled socket, no larger than 20.5mm OD to allow the plug to be fitted. -

In Pursuit of Magic Vol 1 / Issue 2 / July 2021 Dear Readers

community writing project journal vol 1 / issue 2 / July 2021 in pursuit of magic vol 1 / issue 2 / July 2021 Dear Readers As one of my favorite blues singer, Etta James delivered, “At Last,” we are ready with Issue #2 of the Community Writing Project Journal. The overwhelming response to our submis- sion call was delightful. Thank to all of you who gave generously with words and art. Special recognition to ArtSpeak/From Page to Performance participants who continue to regularly submit and support our efforts. A super special thanks to Marcia Klein, Grant Ex- plorer for the CWPJ. She pointed us in the direction of Arts Westchester. All writ- golda Solomon co-editor ers from our premiere issue will be represented in their Spring Exhibition -projects that were initiated during the pandemic. This issue is dedicated to my colleague at Borough of Man- hattan Community College Robert Lapides my first editor, who recently passed away. He saw my potential. “You can talk Golda; how about writing down some of your stories.” I am still talking and writing. Cover art: In Pursuit of Magic (2020) We are proud to introduce a new section, ‘Kidz Roar/Raw, Ysabella Hincapie-Gara unedited contributions from young writers and artists. Our youngest writer is 14 and our youngest artist, four. Editors: Golda Solomon & Jacqueline Reason Artspeak/From Page to Performance Karim Ahmed: Technical Assistant Enjoy our labor of love, Artspeak/From Page to Performance lead a supportive community of Marcia Klein: Grant Hunter meets of each monthly on 2nd writers in exploring poetry, music golda Michele Amaro: Blue Door Art Center Gallery Director Saturdays. -

El Joven Bergoglio, El Adorador 9.195

Georg Gänswein SEMANARIO «Ningún Papa CATÓLICO es sucesor de su DE INFORMACIÓN predecesor, sino Del 8 al 14 de sucesor del apóstol abril de 2021 Pedro» Nº 1.209 Pág. 23 Edición Nacional www.alfayomega.es El Papa Francisco escribe a Alfa y Omega Así fue la Semana Santa del Vaticano MUNDO Francisco celebró por segun- da vez el Triduo Pascual para un aforo reducido de fieles, aunque en strea- El joven Bergoglio, ming para el mundo. Lo hizo acompa- ñado por niños en el vía crucis y por Cantalamessa el Viernes Santo, y fue notable su ausencia del acto litúrgico de la Cena del Señor, ya que lo realizó en privado en la capilla del excardenal el adorador 9.195 Becciu. Editorial y págs. 10-11 MUNDO Los jóvenes hermanos Bergoglio, Jorge Mario y Ós- cionó la fotocopia del libro sobre la adoración nocturna», car, pasaron muchas noches de sábado junto al Santísimo. escribe Francisco de su puño y letra en una carta dirigida a El hoy Papa era el adorador 9.195, según consta en los ar- nuestro colaborador Lucas Schaerer. El Pontífice recuerda Pandemia y cárceles, chivos de la basílica del Santísimo Sacramento de Buenos que la adoración arrancaba «después de la predicación del doble condena Aires, a los que ha tenido acceso Alfa y Omega. «Me emo- padre Aristi», de quien todavía guarda un rosario. Págs. 6-7 MUNDO «Hacinamiento, falta de higie- ne, de atención médica…». A la Comi- sión vaticana COVID-19 llegan con fre- cuencia noticias de la cruda realidad de las cárceles, afirma George Harri- son, del Dicasterio para el Servicio del Desarrollo Humano Integral. -

WITHDRAWN from SALE Hip No

Hip No. Hip No. 561 561 WITHDRAWN FROM SALE Hip No. Consigned by Cleo Harlow Hip No. 562 Streakin Shad 562 February 26, 2012 Bay Filly Smoke Glacken {Two Punch Afrashad TB { Majesty’s Crown Flo White {Whitesburg Streakin Shad Floating Home X0704288 Heza Fast Man SI 111 {The Signature SI 107 Diamonds For Casey SI 87 Fast Copy SI 103 (2000) { Patsy Patrick SI 102 {Hempen TB Easy Verona SI 85 By AFRASHAD TB (2002). Stakes winner of 6 races in 10 starts, ($243,723 USA), in U.S and England, Fall Highweight H. [L], James B. Moseley H. [L], 3rd Sport Page Brdrs’ Cup H. [G3]. His first foals are 3-year-olds of 2013, incl. My Bandera Beauty SI 86 (winner, $17,018, fnl. Remington Park Dis- tance Chlg. [G3]), Flyin Smoak SI 87 (winner, $10,535), Mr Bigtime Gator SI 98 (winner, $6,578), BP Butch SI 89 (winner, $4,725), Believe This SI 86. 1st dam DIAMONDS FOR CASEY SI 87, by Heza Fast Man. Winner to 4, $5,157. Dam of 5 foals of racing age, 3 to race, all winners, including– Ellens Regard SI 90 (f. by Chicks Regard). Winner in 2 starts at 2, 2013, $87,484, 3rd Remington Park Oklahoma Bred Futurity [R]. Volcom Jr SI 90 (g. by Volcom). Winner to 4, 2013, $35,095. 2nd dam Patsy Patrick SI 102, by Hempen TB. 5 wins to 3, $39,916, 2nd Bluestem Downs Spring Futurity, finalist in the Heritage Place Futurity [R] [G2]. Dam of 8 foals, 7 to race, all winners, including– Patsys Patriot SI 95 (g. -

The Popular Culture Studies Journal Volume 8 Number 2

BLACK POPULAR CULTURE THE POPULAR CULTURE STUDIES JOURNAL Volume 8 | Number 2 | September 2020 Special Issue Editor: Dr. Angela Spence Nelson Cover Art: “Wakanda Forever” Dr. Michelle Ferrier POPULAR CULTURE STUDIES JOURNAL VOLUME 8 NUMBER 2 2020 Editor Lead Copy Editor CARRIELYNN D. REINHARD AMY DREES Dominican University Northwest State Community College Managing Editor Associate Copy Editor JULIA LARGENT AMANDA KONKLE McPherson College Georgia Southern University Associate Editor Associate Copy Editor GARRET L. CASTLEBERRY PETER CULLEN BRYAN Mid-America Christian University The Pennsylvania State University Associate Editor Reviews Editor MALYNNDA JOHNSON CHRISTOPHER J. OLSON Indiana State University University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Associate Editor Assistant Reviews Editor KATHLEEN TURNER LEDGERWOOD SARAH PAWLAK STANLEY Lincoln University Marquette University Associate Editor Graphics Editor RUTH ANN JONES ETHAN CHITTY Michigan State University Purdue University Please visit the PCSJ at: mpcaaca.org/the-popular-culture-studies-journal. Popular Culture Studies Journal is the official journal of the Midwest Popular Culture Association and American Culture Association (MPCA/ACA), ISSN 2691-8617. Copyright © 2020 MPCA. All rights reserved. MPCA/ACA, 421 W. Huron St Unit 1304, Chicago, IL 60654 EDITORIAL BOARD CORTNEY BARKO KATIE WILSON PAUL BOOTH West Virginia University University of Louisville DePaul University AMANDA PICHE CARYN NEUMANN ALLISON R. LEVIN Ryerson University Miami University Webster University ZACHARY MATUSHESKI BRADY SIMENSON CARLOS MORRISON Ohio State University Northern Illinois University Alabama State University KATHLEEN KOLLMAN RAYMOND SCHUCK ROBIN HERSHKOWITZ Bowling Green State Bowling Green State Bowling Green State University University University JUDITH FATHALLAH KATIE FREDRICKS KIT MEDJESKY Solent University Rutgers University University of Findlay JESSE KAVADLO ANGELA M. -

¡Sacan a Dos De Su Casa

Página 24 El Mejor Periodismo Diario Zacatecas, Zac. Director General: Ramiro Luévano López Sábado 25 de Septiembre de 2021 Año 22 Número 7632 La Sociedad Zacatecana Merece una Explicación: Ernesto González COVID-19 ya Suma Tres mil 349 Víctimas Página 8 “ Solicitamos a la ASE Haga un En la Búsqueda de Personas Desaparecidas Informe Público Sobre los nos Acompañan la GN, PEP y Sedena: Aguayo Responsables de la Crisis Financiera” * “Nos Sentimos Tranquilos Ante el Tema de Inseguridad Página 6 que Azota a Zacatecas” Página 8 “Monreal Anuncia un Plan de Contingencia Salarial” La CDHEZ Insta Impulsará Gobernador David Monreal la a Autoridades Buscar Descentralización de la Cultura en Zacatecas una Solución a la Problemática de Falta de Pago a Docentes * Es un Tema Complejo, se Requiere el Esfuerzo de To- dos los Órdenes de Gobierno: Luz Domínguez Página 12 Para Proteger a la Población La Vacuna Contra el Covid-19 Llega a los Municipios de Zacatecas Las Brigadas Correcaminos acudieron a los municipios de Jerez, Tepechitlán, Florencia de Benito Juárez... Página 9 Reitera su decisión de lograr una solución de fondo en el tema de la nómina magisterial y del Issstezac Página 4 Mi Jardín de Flores Hablando Ya lo Dijo la Corte Ya es Tiempo de Poner Denuncias Contra Tello de Jorge Por la Madre Teresa de Chalchihuites Por Leticia Bonifaz* Por Silvia Montes Montañez Página 5 y 6 Página 2 Página 7 2 Local/Opinión Sábado 25 de Septiembre de 2021 Página 24 Ya lo Dijo la Corte Por Juan Fernando Reyes Ortega Por Leticia Bonifaz* LA SUPREMA Corte de Justicia de la Na- derecho, pero en otros no. -

Indignación Masiva En Contra De Comisión De Edificios Públicos En La Reunión De La Junta El Miércoles, 80 Personas Se Apuntaron a Tomar La Palabra

AdelitaLa Prensa Noticias Comunitarias Latinas Latino Community News Domingo 30 octubre de 1994 This Edition Completely Bilingual/ Esta edición Completamente Bilingüe Indignación Masiva en Contra de Comisión de Edificios Públicos En la reunión de la Junta el Miércoles, 80 personas se apuntaron a tomar la palabra. De ellos, 56, siendo mayor mente padres de familia y miembros de Concilios Escolares Locales (CEL), hablaban de problemas de sobre población escolar, uso de terreno, y problemas de reparaciones de plantel, todo lo cual se relaciona directamente a la falta de acción por parte de la PBC, o a lo que ellos mismos califi caron como favoritismo por parte de su presidente, el alcalde Richard Daley. Página 3 Public Building Commission Under Fire • At Wednesday’s Board of Education meeting, 80 people Junta de registered to speak to the Board members in the public ses sion. Fifty-six of these, mostly parents and LSC members, Educación Dobla la were speaking about overcrowding, land use, and repair problems which related directly to action or inaction of the Public Building Commission, or to what they labeled polit Rodilla Ante ical favoritism by its chairman, Mayor Daley. ... Page 2 Presión del Board Buckles Under Alcalde en Asunto Mayoral Pressure on de la Escuela Lozano School.. PageLozano 4 ... Página 5 Reunión Tumultuosa de la Junta Directiva de la Policía ... Página 9 Raucous Meeting at the Police Board ... Page 8 Convención Nacional Democrática de México- Cecilia Rodríguez ... Página 15 National Democratic Convention of Mexico - Cecilia Rodriguez ... Page 14 Página 13 — 30 de Octubre de 1994 — Page 13 Medida Anti Inmigrante en California Atrae Atención Mundial Propaganda Abiertamente Fascista Domina las Elecciones en Noviembre La iniciativa anti inmigrante en Al nivel de la base, han sucedido huel California que se conoce como gas escolares en todo el estado. -

NPRC) VIP List, 2009

Description of document: National Archives National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) VIP list, 2009 Requested date: December 2007 Released date: March 2008 Posted date: 04-January-2010 Source of document: National Personnel Records Center Military Personnel Records 9700 Page Avenue St. Louis, MO 63132-5100 Note: NPRC staff has compiled a list of prominent persons whose military records files they hold. They call this their VIP Listing. You can ask for a copy of any of these files simply by submitting a Freedom of Information Act request to the address above. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. -

A Critical Analysis of the Black President in Film and Television

“WELL, IT IS BECAUSE HE’S BLACK”: A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF THE BLACK PRESIDENT IN FILM AND TELEVISION Phillip Lamarr Cunningham A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2011 Committee: Dr. Angela M. Nelson, Advisor Dr. Ashutosh Sohoni Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Michael Butterworth Dr. Susana Peña Dr. Maisha Wester © 2011 Phillip Lamarr Cunningham All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Ph.D., Advisor With the election of the United States’ first black president Barack Obama, scholars have begun to examine the myriad of ways Obama has been represented in popular culture. However, before Obama’s election, a black American president had already appeared in popular culture, especially in comedic and sci-fi/disaster films and television series. Thus far, scholars have tread lightly on fictional black presidents in popular culture; however, those who have tend to suggest that these presidents—and the apparent unimportance of their race in these films—are evidence of the post-racial nature of these texts. However, this dissertation argues the contrary. This study’s contention is that, though the black president appears in films and televisions series in which his presidency is presented as evidence of a post-racial America, he actually fails to transcend race. Instead, these black cinematic presidents reaffirm race’s primacy in American culture through consistent portrayals and continued involvement in comedies and disasters. In order to support these assertions, this study first constructs a critical history of the fears of a black presidency, tracing those fears from this nation’s formative years to the present. -

List of Arcade Games

List of Arcade Games 1) '88 Games 28) Alex Kidd: The Lost Stars 2) 1941: Counter Attack 29) Alien Storm 3) 1942 30) Alien Syndrome 4) 1943: The Battle of Midway 31) Alien vs. Predator 5) 1944: The Loop Master 32) Alien3: The Gun 6) 19XX: The War Against Destiny 33) Aliens 7) 2 on 2 Open Ice Challenge 34) All American Football 8) 2020 Super Baseball 35) Alley Master 9) 3 Count Bout 36) Alligator Hunt 10) 4-D Warriors 37) Alpha Mission 11) 720 Degrees 38) Alpha Mission II 12) 8 Ball Action 39) Alpine Ski 13) APB All-Points Bulletin 40) Altered Beast 14) ASO - Armored Scrum Object 41) Amazing Maze 15) Acrobat Mission 42) Ambush 16) Acrobatic Dog-Fight 43) American Horseshoes 17) Act-Fancer: Cybernetick Hyper Weapon 44) American Speedway 18) Aero Fighters 45) Amidar 19) Aero Fighters 2 / Sonic Wings 2 46) Andro Dunos 20) Aero Fighters 3 / Sonic Wings 3 47) Anteater 21) After Burner 48) Appoooh 22) After Burner II 49) Aqua Jack 23) Aggressors of Dark Kombat 50) Aquarium 24) Air Duel 51) Arabian 25) Air Gallet 52) Arabian Fight 26) Airwolf 53) Arabian Magic 27) Ajax 54) Arbalester 55) Arch Rivals 84) Azurian Attack 56) Argus 85) Back Street Soccer 57) Ark Area 86) Bad Dudes Vs. DragonNinja 58) Arkanoid 87) Bad Lands 59) Arkanoid Returns 88) Bagman 60) Arkanoid: Revenge of DOH 89) Balloon Bomber 61) Arm Wrestling 90) Balloon Brothers 62) Armed Formation F 91) Bang 63) Armed Police Batrider 92) Bang Bead 64) Armor Attack 93) Barrier 65) Armored Car 94) Baseball Stars 2 66) Armored Warriors 95) Baseball Stars Professional 67) Art Of Fighting 96) Basketball 68) Art of Fighting 2 97) Batman 69) Ashura Blaster 98) Batsugun 70) Assault 99) Battle Balls 71) Asterix 100) Battle Chopper 72) Asteroids 101) Battle Circuit 73) Asteroids Deluxe 102) Battle City 74) Astro Blaster 103) Battle Cross 75) Astro Fighter 104) Battle Flip Shot 76) Astro Invader 105) Battle K-Road 77) Asuka & Asuka 106) Battle Lane Vol. -

Print Format

Paideia High School Summer Reading 2021 © Paideia School Library, 1509 Ponce de Leon Avenue, NE. Atlanta, Georgia 30307 (404) 377-3491 PAIDEIA HIGH SCHOOL Summer Reading Program Marianne Hines – All High School students should read a minimum of THREE books “Standing at the Crossroads” – Read THREE books by American over the summer. See below for any specific books assigned for your authors (of any racial or ethnic background) and be prepared to write grade and/or by your fall term English teacher. You will write about your first paper on one of these books. your summer reading at the beginning of the year. Free choice books can be chosen from the High School summer Tally Johnson – Read this book, plus TWO free choice books = reading booklet, or choose any other books that intrigue you. THREE total Need help deciding on a book, or have other questions? “The Ties That Bind Us” – Little Fires Everywhere by Celeste Ng Email English teacher Marianne Hines at [email protected] Sarah Schiff – Read this book plus TWO free choice books = THREE total or librarian Anna Watkins at [email protected]. "Yearning to Breathe Free” – Kindred by Octavia Butler. 9th & 10th grade summer reading Jim Veal – Read the assigned book plus TWO free choice books = THREE total Read any THREE fiction or non-fiction books of your own choosing. “The American West” – Shane by Jack Schaefer “Coming Across” – The Best We Could Do by Thi Bui 11th & 12th grade summer reading by teacher and class If your fall term English teacher has not listed specific assignments, read a total of THREE fiction or non-fiction books of your own choice.