ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: SISTERS in the SPIRIT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Latin American Agenda 2016

World Latin American Agenda 2016 In its category, the Latin American book most widely distributed inside and outside the Americas each year. A sign of continental and global communion among individuals and communities excited by and committed to the Great Causes of the Patria Grande. An Agenda that expresses the hope of the world’s poor from a Latin American perspective. A manual for creating a different kind of globalization. A collection of the historical memories of militancy. An anthology of solidarity and creativity. A pedagogical tool for popular education, communication and social action. From the Great Homeland to the Greater Homeland. Our cover image by Maximino CEREZO BARREDO. See all our history, 25 years long, through our covers, at: latinoamericana.org/digital /desde1992.jpg and through the PDF files, at: latinoamericana.org/digital This year we remind you... We put the accent on vision, on attitude, on awareness, on education... Obviously, we aim at practice. However our “charisma” is to provoke the transformations of awareness necessary so that radically new practices might arise from another systemic vision and not just reforms or patches. We want to ally ourselves with all those who search for that transformation of conscience. We are at its service. This Agenda wants to be, as always and even more than at other times, a box of materials and tools for popular education. latinoamericana.org/2016/info is the web site we have set up on the network in order to offer and circulate more material, ideas and pedagogical resources than can economically be accommo- dated in this paper version. -

Fitment Chart (Pdf)

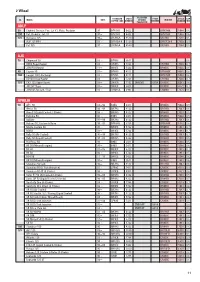

2 Wheel PLATINUM CC MODEL DATE STANDARD STOCK OR GOLD STOCK IRIDIUM STOCK GAP COPPER CORE NUMBER PALLADIUM NUMBER NUMBER MM ADLY 50 Citybird, Crosser, Fox, Jet X1, Pista, Predator 97 BPR7HS 6422 BPR7HIX 5944 0.6 100 Cat, Predator, Jet, X1 97 BPR7HS 6422 BPR7HIX 5944 0.6 125 Activator 125 99 CR7HSA 4549 CR7HIX 7544 0.5 AJP 125 PR4 03 DPR7EA-9 5129 DPR7EIX-9 7803 0.9 Cat 125 97 CR7HSA 4549 CR7HIX 7544 0.5 AJS 50 Chipmunk 50 03 BP4HS 3611 0.6 DD50 Regal Raptor 03 CR7HS 7223 CR7HIX 7544 0.7 JSM 50 Motard 11 BR8ES 5422 BR8EIX 5044 0.6 80 Coyote 80 03 BP6HS 4511 BPR6HIX 4085 0.6 100 Cougar 100 (Jincheng) 03 BP7HS 5111 BPR7HIX 5944 0.6 DD100 Regal Raptor 03 CR7HS 7223 CR7HIX 7544 0.7 125 CR3-125 Super Sports 08 DR8EA 7162 DR8EVX 6354 DR8EIX 6681 0.6 JS125Y Tiger 03 DR8ES 5423 DR9EIX 4772 0.7 JSM125 Motard / Trail 10 CR6HSA 2983 CR6HIX 7274 0.6 APRILIA 50 AF1 50 8892 B8ES 2411 BR8EIX 5044 0.5 Amico 50 9294 BR7HS 4122 BR7HIX 7067 0.6 Area 51 (Liquid Cooled 2-Stroke) 98 BR8HS 4322 BR8HIX 7001 0.5 Extrema 50 93 B8ES 2411 BR8EIX 5044 0.5 Gulliver 9799 BR7HS 4122 BR7HIX 7067 0.6 Habana 50, Custom & Retro 9905 BPR8HS 3725 BPR8HIX 6742 0.6 Mojito Custom 50 05 BR9ES 5722 BR9EIX 3981 0.7 MX50 03 BR9ES 5722 BR9EIX 3981 0.7 Rally 50 (Air Cooled) 9599 BR7HS 4122 BR7HIX 7067 0.7 Rally 50 (Liquid Cooled) 9703 BR8HS 4322 BR8HIX 7001 0.5 Red Rose 50 93 B8ES 2411 BR8EIX 5044 0.5 RS 50 (Minarelli engine) 93 B8ES 2411 BR8EIX 5044 0.6 RS 50 0105 BR9ES 5722 BR9EIX 3981 0.7 RS 50 06 BR9ES 5722 BR9EIX 3981 0.5 RS4 50 1113 BR8ES 5422 BR8EIX 5044 0.6 ‡ Early Ducati Testastretta bikes (749, 998, 999 models) can have very little clearance between the plug hex and the RX 50 (Minarelli engine) 97 B9ES 2611 BR9EIX 3981 0.6 cylinder head that may require a thin walled socket, no larger than 20.5mm OD to allow the plug to be fitted. -

Literature As History; History in Literature

MEJO The MELOW Journal of World Literature February 2018 ISSN: Applied For A peer refereed journal published annually by MELOW (The Society for the Study of the Multi-Ethnic Literatures of the World) Facts, Distortions and Erasures: Literature as History; History in Literature Editor Manpreet Kaur Kang 1 Editor Manpreet Kaur Kang, Professor of English, Guru Gobind Singh IP University, Delhi Email: [email protected] Editorial Board: Anil Raina, Professor of English, Panjab University Email: [email protected] Debarati Bandyopadhyay, Professor of English, Viswa Bharati, Santiniketan Email: [email protected] Himadri Lahiri, Professor of English, University of Burdwan Email: [email protected] Manju Jaidka, Professor of English, Panjab University Email: [email protected] Neela Sarkar, Associate Professor, New Alipore College, W.B. Email: [email protected] Rimika Singhvi, Associate Professor, IIS University, Jaipur Email: [email protected] Roshan Lal Sharma, Dean and Associate Professor, Central University of Himachal Pradesh, Dharamshala Email: [email protected] 2 EDITORIAL NOTE MEJO, or the MELOW Journal of World Literature, is a peer-refereed Ejournal brought out biannually by MELOW, the Society for the Study of the Multi-Ethnic Literatures of the World. It is a reincarnation of the previous publications brought out in book or printed form by the Society right since its inception in 1998. MELOW is an academic organization, one of the foremost of its kind in India. The members are college and university teachers, scholars and critics interested in literature, particularly in World Literatures. The Organization meets almost every year over an international conference. -

A Study of Similarities Between Dalit Literature and African-American Literature

A STUDY OF SIMILARITIES BETWEEN DALIT LITERATURE AND AFRICAN-AMERICAN LITERATURE J. KAVI KALPANA K. SARANYA Ph.D Research Scholars Ph.D Research Scholars Department of English Department of English Presidency College Presidency College Chennai. (TN) INDIA Chennai. (TN) INDIA Dalit literature is the literature which artistically portrays the sorrows, tribulations, slavery degradation, ridicule and poverty endured by Dalits. Dalit literature has a great historical significance. Its form and objective were different from those of the other post-independence literatures. The mobilization of the oppressed and exploited sections of the society- the peasants, Dalits, women and low caste occurred on a large scale in the 1920s and 1930s,under varying leaderships and with varying ideologies. Its presence was noted in India and abroad. On the other hand African American writing primarily focused on the issue of slavery, as indicated by the subgenre of slave narratives. The movement of the African Americans led by Martin Luther King and the activities of black panthers as also the “Little Magazine” movement as the voice of the marginalized proved to be a background trigger for resistance literature of Dalits in India. In this research paper the main objective is to draw similarities between the politics of Caste and Race in Indian Dalit literature and the Black American writing with reference to Bama’s Karukku and Alice Walker’s The Color Purple. Keywords: Dalit Literature, African American writings, marginalized, Slave narratives, Black panthers, Untouchable, Exploitation INTRODUCTION In the words of Arjun Dangle, “Dalit literature is one which acquaints people with the caste system and untouchability in India. -

The Speculative Fiction of Octavia Butler and Tananarive Due

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Digital Commons@Wayne State University Wayne State University DigitalCommons@WayneState Wayne State University Dissertations 1-1-2010 An Africentric Reading Protocol: The pS eculative Fiction Of Octavia Butler And Tananarive Due Tonja Lawrence Wayne State University, Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Recommended Citation Lawrence, Tonja, "An Africentric Reading Protocol: The peS culative Fiction Of Octavia Butler And Tananarive Due" (2010). Wayne State University Dissertations. Paper 198. This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. AN AFRICENTRIC READING PROTOCOL: THE SPECULATIVE FICTION OF OCTAVIA BUTLER AND TANANARIVE DUE by TONJA LAWRENCE DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2011 MAJOR: COMMUNICATION Approved by: __________________________________________ Advisor Date __________________________________________ __________________________________________ __________________________________________ __________________________________________ © COPYRIGHT BY TONJA LAWRENCE 2011 All Rights Reserved DEDICATION To my children, Taliesin and Taevon, who have sacrificed so much on my journey of self-discovery. I have learned so much from you; and without that knowledge, I could never have come this far. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am deeply grateful for the direction of my dissertation director, help from my friends, and support from my children and extended family. I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my dissertation director, Dr. Mary Garrett, for exceptional support, care, patience, and an unwavering belief in my ability to complete this rigorous task. -

In Pursuit of Magic Vol 1 / Issue 2 / July 2021 Dear Readers

community writing project journal vol 1 / issue 2 / July 2021 in pursuit of magic vol 1 / issue 2 / July 2021 Dear Readers As one of my favorite blues singer, Etta James delivered, “At Last,” we are ready with Issue #2 of the Community Writing Project Journal. The overwhelming response to our submis- sion call was delightful. Thank to all of you who gave generously with words and art. Special recognition to ArtSpeak/From Page to Performance participants who continue to regularly submit and support our efforts. A super special thanks to Marcia Klein, Grant Ex- plorer for the CWPJ. She pointed us in the direction of Arts Westchester. All writ- golda Solomon co-editor ers from our premiere issue will be represented in their Spring Exhibition -projects that were initiated during the pandemic. This issue is dedicated to my colleague at Borough of Man- hattan Community College Robert Lapides my first editor, who recently passed away. He saw my potential. “You can talk Golda; how about writing down some of your stories.” I am still talking and writing. Cover art: In Pursuit of Magic (2020) We are proud to introduce a new section, ‘Kidz Roar/Raw, Ysabella Hincapie-Gara unedited contributions from young writers and artists. Our youngest writer is 14 and our youngest artist, four. Editors: Golda Solomon & Jacqueline Reason Artspeak/From Page to Performance Karim Ahmed: Technical Assistant Enjoy our labor of love, Artspeak/From Page to Performance lead a supportive community of Marcia Klein: Grant Hunter meets of each monthly on 2nd writers in exploring poetry, music golda Michele Amaro: Blue Door Art Center Gallery Director Saturdays. -

Towards a Dialogic Understanding of Print Media Stories About

TOWARDS A DIALOGIC UNDERSTANDING OF PRINT MEDIA STORIES ABOUT BLACK/WHITE INTERRACIAL FAMILIES by VICTOR KULKOSKY (Under the Direction of Dwight E. Brooks) ABSTRACT This thesis examines print media news stories about Black/White interracial families from 1990-2003. Using the concept of dialogism, I conduct a textual analysis of selected newspaper and news magazine stories to examine the dialogic interaction between dominant and resistant discourses of racial identity. My findings suggest that a multiracial identity project can be seen emerging in print media stories about interracial families, but the degree to which this project is visible depends on each journalist’s placement of individual voices and discourses within the narrative of each story. I find some evidence of a move from placing interracial families within narratives of conflict toward a more optimistic view of such families’ position in society. INDEX WORDS: Interracial marriage, Multiracial identity, Multiracial families, Race relations, Dialogism, Bakhtin, Media discourse, Newspapers, African American media, Interracial sexuality, Baha’i Faith TOWARDS A DIALOGIC UNDERSTANDING OF PRINT MEDIA STORIES ABOUT BLACK/WHITE INTERRACIAL FAMILIES by VICTOR KULKOSKY B.A., Fort Valley State University, 1998 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2003 © 2003 Victor Kulkosky All Rights Reserved TOWARDS A DIALOGIC UNDERSTANDING OF PRINT MEDIA STORIES ABOUT BLACK/WHITE INTERRACIAL FAMILIES by VICTOR KULKOSKY Major Professor: Dwight E. Brooks Committee: Carolina Acosta- Alzuru Ruth Ann Lariscy Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia December 2003 iv DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my wife, Terri Lenisa Earl-Kulkosky, my son, Gregory Badi Earl-Kulkosky, and my niece, Alyson Simone Nicole Allen. -

Racial Hybridity in Danzy Senna’S Caucasia

Arnett 1 Alyx Arnett Dr. Eva White E304 16 December 2009 Racial Attitudes in the United States: Racial Hybridity in Danzy Senna’s Caucasia The United States, once a slave-owning society, has made substantial progress in decreasing the injustices and mistreatment toward black racial minorities and hybrids since the early 1900s. In the 1880s, Jim Crow laws were passed, legalizing segregation between blacks and whites. Then, in 1896, the Supreme Court case Plessy v. Ferguson ruled that “separate facilities for whites and blacks were constitutional” (“Jim Crow Laws”). Afterward, virtually every part of society was segregated, and new institutions such as schools and hospitals had to be created specifically for blacks. But in 1965, a turning point came in American society when another Supreme Court case, Brown v. Board of Education, declared that facilities separated on the basis of race were unconstitutional. During that time, the Civil Rights Act was passed along with the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the Fair Housing Act of 1968 to provide blacks with rights that they had previously been denied (“Jim Crow Laws”). It is during this shift in American society that Birdie Lee is born. Through the perspective of this biracial speaker growing up in the liminal space between racism and acceptance, Danzy Senna’s Caucasia provides readers with a view of the shifting attitudes and increased tolerance of racial hybridity in the United States. In the beginning of the novel, Birdie makes it clear that racial relations are about to change in Boston. She says: Arnett 2 A long time ago I disappeared . -

El Joven Bergoglio, El Adorador 9.195

Georg Gänswein SEMANARIO «Ningún Papa CATÓLICO es sucesor de su DE INFORMACIÓN predecesor, sino Del 8 al 14 de sucesor del apóstol abril de 2021 Pedro» Nº 1.209 Pág. 23 Edición Nacional www.alfayomega.es El Papa Francisco escribe a Alfa y Omega Así fue la Semana Santa del Vaticano MUNDO Francisco celebró por segun- da vez el Triduo Pascual para un aforo reducido de fieles, aunque en strea- El joven Bergoglio, ming para el mundo. Lo hizo acompa- ñado por niños en el vía crucis y por Cantalamessa el Viernes Santo, y fue notable su ausencia del acto litúrgico de la Cena del Señor, ya que lo realizó en privado en la capilla del excardenal el adorador 9.195 Becciu. Editorial y págs. 10-11 MUNDO Los jóvenes hermanos Bergoglio, Jorge Mario y Ós- cionó la fotocopia del libro sobre la adoración nocturna», car, pasaron muchas noches de sábado junto al Santísimo. escribe Francisco de su puño y letra en una carta dirigida a El hoy Papa era el adorador 9.195, según consta en los ar- nuestro colaborador Lucas Schaerer. El Pontífice recuerda Pandemia y cárceles, chivos de la basílica del Santísimo Sacramento de Buenos que la adoración arrancaba «después de la predicación del doble condena Aires, a los que ha tenido acceso Alfa y Omega. «Me emo- padre Aristi», de quien todavía guarda un rosario. Págs. 6-7 MUNDO «Hacinamiento, falta de higie- ne, de atención médica…». A la Comi- sión vaticana COVID-19 llegan con fre- cuencia noticias de la cruda realidad de las cárceles, afirma George Harri- son, del Dicasterio para el Servicio del Desarrollo Humano Integral. -

WITHDRAWN from SALE Hip No

Hip No. Hip No. 561 561 WITHDRAWN FROM SALE Hip No. Consigned by Cleo Harlow Hip No. 562 Streakin Shad 562 February 26, 2012 Bay Filly Smoke Glacken {Two Punch Afrashad TB { Majesty’s Crown Flo White {Whitesburg Streakin Shad Floating Home X0704288 Heza Fast Man SI 111 {The Signature SI 107 Diamonds For Casey SI 87 Fast Copy SI 103 (2000) { Patsy Patrick SI 102 {Hempen TB Easy Verona SI 85 By AFRASHAD TB (2002). Stakes winner of 6 races in 10 starts, ($243,723 USA), in U.S and England, Fall Highweight H. [L], James B. Moseley H. [L], 3rd Sport Page Brdrs’ Cup H. [G3]. His first foals are 3-year-olds of 2013, incl. My Bandera Beauty SI 86 (winner, $17,018, fnl. Remington Park Dis- tance Chlg. [G3]), Flyin Smoak SI 87 (winner, $10,535), Mr Bigtime Gator SI 98 (winner, $6,578), BP Butch SI 89 (winner, $4,725), Believe This SI 86. 1st dam DIAMONDS FOR CASEY SI 87, by Heza Fast Man. Winner to 4, $5,157. Dam of 5 foals of racing age, 3 to race, all winners, including– Ellens Regard SI 90 (f. by Chicks Regard). Winner in 2 starts at 2, 2013, $87,484, 3rd Remington Park Oklahoma Bred Futurity [R]. Volcom Jr SI 90 (g. by Volcom). Winner to 4, 2013, $35,095. 2nd dam Patsy Patrick SI 102, by Hempen TB. 5 wins to 3, $39,916, 2nd Bluestem Downs Spring Futurity, finalist in the Heritage Place Futurity [R] [G2]. Dam of 8 foals, 7 to race, all winners, including– Patsys Patriot SI 95 (g. -

The Popular Culture Studies Journal Volume 8 Number 2

BLACK POPULAR CULTURE THE POPULAR CULTURE STUDIES JOURNAL Volume 8 | Number 2 | September 2020 Special Issue Editor: Dr. Angela Spence Nelson Cover Art: “Wakanda Forever” Dr. Michelle Ferrier POPULAR CULTURE STUDIES JOURNAL VOLUME 8 NUMBER 2 2020 Editor Lead Copy Editor CARRIELYNN D. REINHARD AMY DREES Dominican University Northwest State Community College Managing Editor Associate Copy Editor JULIA LARGENT AMANDA KONKLE McPherson College Georgia Southern University Associate Editor Associate Copy Editor GARRET L. CASTLEBERRY PETER CULLEN BRYAN Mid-America Christian University The Pennsylvania State University Associate Editor Reviews Editor MALYNNDA JOHNSON CHRISTOPHER J. OLSON Indiana State University University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Associate Editor Assistant Reviews Editor KATHLEEN TURNER LEDGERWOOD SARAH PAWLAK STANLEY Lincoln University Marquette University Associate Editor Graphics Editor RUTH ANN JONES ETHAN CHITTY Michigan State University Purdue University Please visit the PCSJ at: mpcaaca.org/the-popular-culture-studies-journal. Popular Culture Studies Journal is the official journal of the Midwest Popular Culture Association and American Culture Association (MPCA/ACA), ISSN 2691-8617. Copyright © 2020 MPCA. All rights reserved. MPCA/ACA, 421 W. Huron St Unit 1304, Chicago, IL 60654 EDITORIAL BOARD CORTNEY BARKO KATIE WILSON PAUL BOOTH West Virginia University University of Louisville DePaul University AMANDA PICHE CARYN NEUMANN ALLISON R. LEVIN Ryerson University Miami University Webster University ZACHARY MATUSHESKI BRADY SIMENSON CARLOS MORRISON Ohio State University Northern Illinois University Alabama State University KATHLEEN KOLLMAN RAYMOND SCHUCK ROBIN HERSHKOWITZ Bowling Green State Bowling Green State Bowling Green State University University University JUDITH FATHALLAH KATIE FREDRICKS KIT MEDJESKY Solent University Rutgers University University of Findlay JESSE KAVADLO ANGELA M. -

¡Sacan a Dos De Su Casa

Página 24 El Mejor Periodismo Diario Zacatecas, Zac. Director General: Ramiro Luévano López Sábado 25 de Septiembre de 2021 Año 22 Número 7632 La Sociedad Zacatecana Merece una Explicación: Ernesto González COVID-19 ya Suma Tres mil 349 Víctimas Página 8 “ Solicitamos a la ASE Haga un En la Búsqueda de Personas Desaparecidas Informe Público Sobre los nos Acompañan la GN, PEP y Sedena: Aguayo Responsables de la Crisis Financiera” * “Nos Sentimos Tranquilos Ante el Tema de Inseguridad Página 6 que Azota a Zacatecas” Página 8 “Monreal Anuncia un Plan de Contingencia Salarial” La CDHEZ Insta Impulsará Gobernador David Monreal la a Autoridades Buscar Descentralización de la Cultura en Zacatecas una Solución a la Problemática de Falta de Pago a Docentes * Es un Tema Complejo, se Requiere el Esfuerzo de To- dos los Órdenes de Gobierno: Luz Domínguez Página 12 Para Proteger a la Población La Vacuna Contra el Covid-19 Llega a los Municipios de Zacatecas Las Brigadas Correcaminos acudieron a los municipios de Jerez, Tepechitlán, Florencia de Benito Juárez... Página 9 Reitera su decisión de lograr una solución de fondo en el tema de la nómina magisterial y del Issstezac Página 4 Mi Jardín de Flores Hablando Ya lo Dijo la Corte Ya es Tiempo de Poner Denuncias Contra Tello de Jorge Por la Madre Teresa de Chalchihuites Por Leticia Bonifaz* Por Silvia Montes Montañez Página 5 y 6 Página 2 Página 7 2 Local/Opinión Sábado 25 de Septiembre de 2021 Página 24 Ya lo Dijo la Corte Por Juan Fernando Reyes Ortega Por Leticia Bonifaz* LA SUPREMA Corte de Justicia de la Na- derecho, pero en otros no.