Built with Empty Fists: the Rise and Circulation of Black Power Martial Artistry During the Cold War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Use This Guide

How to Use this Guide The New-York Historical Society, one of America’s pre-eminent cultural institutions, is dedicated to fostering research, presenting history and art exhibitions, and public programs that reveal the dynamism of history and its influence on the world of today. Founded in 1804, New-York Historical has a mission to explore the richly layered political, cultural and social history of New York City and State and the nation, and to serve as a national forum for the discussion of issues surrounding the making and meaning of history. Student Historians are high school interns at New-York Historical who explore our museum and library collection and conduct research using the resources available to them within a museum setting. Their project this academic year was to create a guide for fellow high school students preparing for U.S. History Exams, particularly the U.S. History & Government Regents Exam. Each Student Historian chose a piece from our collection that represents a historical event or theme often tested on the exam, collected and organized their research, and wrote about their piece within its historic context. The intent is that this catalog will provide a valuable supplemental review material for high school students preparing for U.S. History Exams. The following summative essays are all researched and written by the 2015-16 Student Historians, compiled in chronological order, and organized by unit. Each essay includes an image of the object or artwork from the N-YHS collection that serves as the foundation for the U.S. History content reviewed. Additional educational supplementary materials include a glossary of frequently used terms, review activities including a crossword puzzle as well as questions and answers taken from past U.S. -

2021 Record Book 5 Single-Season Records

PROGRAM RECORDS TEAM INDIVIDUAL Game Game Goals .......................................................11 vs. Old Dominion, 10/1/71 Goals .................................................. 5, Bill Hodill vs. Davidson, 10/17/42 ............................................................11 vs. Richmond, 10/20/81 Assists ................................................. 4, Damian Silvera vs. UNC, 9/27/92 Assists ......................................................11 vs. Virginia Tech, 9/14/94 ..................................................... 4, Richie Williams vs. VCU, 9/13/89 Points .................................................................... 30 vs. VCU, 9/13/89 ........................................... 4, Kris Kelderman vs. Charleston, 9/10/89 Goals Allowed .................................................12 vs. Maryland, 10/8/41 ...........................................4, Chick Cudlip vs. Wash. & Lee, 11/13/62 Margin of Victory ....................................11-0 vs. Old Dominion, 10/1/71 Points ................................................ 10, Bill Hodill vs. Davidson, 10/17/42 Fastest Goal to Start Match .........................................................11-0 vs. Richmond, 10/20/81 .................................:09, Alecko Eskandarian vs. American, 10/26/02* Margin of Defeat ..........................................12-0 vs. Maryland, 10/8/41 Largest Crowd (Scott) .......................................7,311 vs. Duke, 10/8/88 *Tied for 3rd fastest in an NCAA Soccer Game Largest Crowd (Klöckner) ......................7,906 -

1St Annual Walter Rodney Speakers Series (2013)

Groundings Volume 1 | Issue 1 Article 4 September 2014 1st Annual Walter Rodney Speakers Series (2013) Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/groundings Part of the African History Commons, African Studies Commons, Growth and Development Commons, International Relations Commons, Labor Economics Commons, Political Economy Commons, Political Theory Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, and the Work, Economy and Organizations Commons Recommended Citation (2014) "1st Annual Walter Rodney Speakers Series (2013)," Groundings: Vol. 1 : Iss. 1 , Article 4. Available at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/groundings/vol1/iss1/4 This Front Matter is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Groundings by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Groundings (2014) 1(1) : Page 6 WALTER RODNEY SPEAKER’S SERIES ---- REPORT The 1st Annual Walter Rodney Speaker’s Series January - May, 2013 Thursdays, 5-7pm at the Atlanta University Center Robert W. Woodruff Library OVERVIEW Professor Jesse Benjamin, with generous base-support from a Georgia Humanities Council Grant, the AUC Robert W. Woodruff Library, the Walter Rodney Foundation, Kennesaw State University, and Clark Atlanta University, established a (now annual) public lecture series that explores the life and work of Dr. Walter Rodney and his core contributions to Pan-Africanism, development theory, emancipatory pedagogy, and theories of race and class in the Caribbean, Africa and the rest of the world. This project seeks to keep Dr. -

Copyright by Jacob Charles Maguire 2011

Copyright by Jacob Charles Maguire 2011 The Report Committee for Jacob Charles Maguire Certifies that this is the approved version of the following report: “Though It Blasts Their Eyes”: Slavery and Citizenship in New York City, 1790-1821 APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Shirley Thompson Jeffrey Meikle “Though It Blasts Their Eyes”: Slavery and Citizenship in New York City, 1790-1821 by Jacob Charles Maguire, B.A. Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2011 Dedication For my dad, who always taught me about citizenship Abstract “Thought It Blasts Their Eyes”: Slavery and Citizenship in New York City, 1790-1821 Jacob Charles Maguire, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2011 Supervisor: Shirley Thompson Between 1790 and 1821, New York City underwent a dramatic transformation as slavery slowly died. Throughout the 1790s, a massive influx of runaways from the hinterland and black refugees from the Caribbean led to the rapid expansion of the city’s free black population. At the same time, white agitation for abolition reached a fever pitch. The legislature’s decision in 1799 to enact a program of gradual emancipation set off a wave of arranged manumissions that filled city streets with black bodies at all stages of transition from slavery to freedom. As blacks began to organize politically and develop a distinct social, economic and cultural life, they both conformed to and defied white expectations of republican citizenship. -

To View the Sankofa African Heritage Book List

A B C D E F COPY- TITLE AUTHORS ED PUBLISHER(S) COVER ANNOTATION 1 RIGHT African Origins of the Majors Yosef Ben jochannan 1970- All Western religions had 2 Western Religions Yosef Ben Jochannan Publishing 360pp Paper their beginnings in Africa The Encyclopedia of the 1999- African and African American 3 AFRICANA Kwame-Gates, editors Basic Civitas Books 2045pp Cloth Experience 2002- 4 Africans Americans David Boyle Barrons 127pp Cloth Coming to America Today, we live in a changed Al on America, The Right Reverend Kingsenton Publishing 2002- America, changed by people 5 Al Sharpton Karen Hunter Group 280pp Cloth who risk their own lives. 2009- What Should Black People Do 6 America I Am Legends Foreword : Tavis Smiley Smiley books 180pp Paper Now? Untold Tales of the First Pilgrims, Fighting Women, 2008- and Forgotten Founders who 7 America's Hidden History Kenneth C. Davis Smithsonian Books 265pp Cloth shaped a Nation Ancient Egypt, The Light of the 1990- A work of reclamation and 8 World,Vol 1-B and vol.2--A Gerald Massey ECA Associates 750pp Paper restitution in twelve volumes The teaching and prophetic wisdom of the Seven 1999- Hermetic laws of Ancient 9 Ancient Future Wayne B. Chandler Black Classic Press 246pp Paper Egypt 2009- The U.S. Commission on Civil 10 And Justice For All Mary Frances Berry Knopf Publishers 425pp Cloth Rights 1995- Everyday liife ritual and court 11 Art and Craft in Africa Laure Meyer Terrial Publishers, Montreal 208pp Paper art B.B. King and Dick 2005- Collection of treasures of 12 B.B.King- Treasures Waterman Bulfinch Press 160pp cloth B.B. -

World Latin American Agenda 2016

World Latin American Agenda 2016 In its category, the Latin American book most widely distributed inside and outside the Americas each year. A sign of continental and global communion among individuals and communities excited by and committed to the Great Causes of the Patria Grande. An Agenda that expresses the hope of the world’s poor from a Latin American perspective. A manual for creating a different kind of globalization. A collection of the historical memories of militancy. An anthology of solidarity and creativity. A pedagogical tool for popular education, communication and social action. From the Great Homeland to the Greater Homeland. Our cover image by Maximino CEREZO BARREDO. See all our history, 25 years long, through our covers, at: latinoamericana.org/digital /desde1992.jpg and through the PDF files, at: latinoamericana.org/digital This year we remind you... We put the accent on vision, on attitude, on awareness, on education... Obviously, we aim at practice. However our “charisma” is to provoke the transformations of awareness necessary so that radically new practices might arise from another systemic vision and not just reforms or patches. We want to ally ourselves with all those who search for that transformation of conscience. We are at its service. This Agenda wants to be, as always and even more than at other times, a box of materials and tools for popular education. latinoamericana.org/2016/info is the web site we have set up on the network in order to offer and circulate more material, ideas and pedagogical resources than can economically be accommo- dated in this paper version. -

Student Evaluations of Experiences in African-Centered Educational Institutions

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University African-American Studies Theses Department of African-American Studies 5-7-2016 Looking Back to Go Forward: Student Evaluations of Experiences in African-Centered Educational Institutions Ivan N. Vassall III Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses Recommended Citation Vassall, Ivan N. III, "Looking Back to Go Forward: Student Evaluations of Experiences in African-Centered Educational Institutions." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2016. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses/34 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of African-American Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in African-American Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LOOKING BACK TO GO FORWARD: STUDENT EVALUATIONS OF EXPERIENCES IN AFRICAN-CENTERED EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS by IVAN N. VASSALL III Under the Direction of Makungu Akinyela, PhD ABSTRACT In educational research, a prevalent topic of discussion is African-centered pedagogy. This phenomenological study records the unique perspectives of adults who specifically grew up in African-centered learning environments from a young age. The sample includes 10 African American adults, aged 18-45, from various cities in the United States. Mixed methods are applied in this study: group concept mapping strategies are implemented to yield both qualitative and quantitative results for analysis. Data is further supplemented with one-on-one interviews, and a review of themes from interview transcripts using multiple coding processes. Findings from this particular demographic can add another dimension to the current literature on the relevancy and need for culturally relevant pedagogical practice for African-American children. -

The Terena and the Caduveo of Southern Mato Grosso, Brazil

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION n INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL ANTHROPOLOQY H PUBLICATION NO. 9 THE TERENA AND THE CADUVEO OF SOUTHERN MATO GROSSO, BRAZIL by KALERVO OBERG Digitalizado pelo Internet Archive. Disponível na Biblioteca Digital Curt Nimuendaju: http://biblio.etnolinguistica.org/oberg_1949_terena SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL ANTHROPOLOGY PUBLICATION NO. 9 THE TERENA AND THE CADUVEO OF SOUTHERN MATO GROSSO, BRAZIL by KALERVO OBERG Prepared in Cooperation tiith the United States Department of State as a Project of the Interdrpartmental Committee on Scientific and Cultural Cooperation UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PIIINTING OFFICE-WASHINGTON:1949 For Bale by the Superintendent of Documenn, U.^S. Government Printing Office, WaohinBton 25, D. C. • Price 60 c LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL Smithsonian Institution, Institute of Social Anthropology, WashinfftonSS, D. C, May 6, 1948 Sir: I have the honor to transmit herewith a manuscript entitled "The Terena and the Caduveo of Soutliern Mato Grosso, Brazil," by Kalervo Oberg, and to recommend that it be published as Publication Number 9 of the Institute of Social Anthropologj'. Very respectfully yours, George M. Foster, Director. Dr. Alexander Wetmore, Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. CONTENTS PAGE The Terena—Continued page Introduction 1 The hfe cycle 38 The Terena 6 Birth (ipuhicoti-hiuki) 38 Terena economy in the Chaco 6 Puberty 39 Habitat 6 Marriage (koyendti) 39 Shelter 8 Burial 40 Clothing and ornaments 9 Collecting, hunting, and fishing 9 Modern changes 41 Agriculture 10 Religion 41 Domestic animals and birds 12 Rehgious beliefs 41 Manufactures 12 Shamanism 43 Raiding 13 Present-day religion 45 Property and inheritance 13 Secular entertainment 47 Organization of labor 13 Dances and games 47 Present-day economy of the Terena 13 General description 13 Football 51 Sources of income in a typical village. -

Fitment Chart (Pdf)

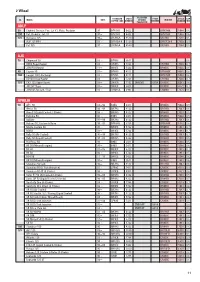

2 Wheel PLATINUM CC MODEL DATE STANDARD STOCK OR GOLD STOCK IRIDIUM STOCK GAP COPPER CORE NUMBER PALLADIUM NUMBER NUMBER MM ADLY 50 Citybird, Crosser, Fox, Jet X1, Pista, Predator 97 BPR7HS 6422 BPR7HIX 5944 0.6 100 Cat, Predator, Jet, X1 97 BPR7HS 6422 BPR7HIX 5944 0.6 125 Activator 125 99 CR7HSA 4549 CR7HIX 7544 0.5 AJP 125 PR4 03 DPR7EA-9 5129 DPR7EIX-9 7803 0.9 Cat 125 97 CR7HSA 4549 CR7HIX 7544 0.5 AJS 50 Chipmunk 50 03 BP4HS 3611 0.6 DD50 Regal Raptor 03 CR7HS 7223 CR7HIX 7544 0.7 JSM 50 Motard 11 BR8ES 5422 BR8EIX 5044 0.6 80 Coyote 80 03 BP6HS 4511 BPR6HIX 4085 0.6 100 Cougar 100 (Jincheng) 03 BP7HS 5111 BPR7HIX 5944 0.6 DD100 Regal Raptor 03 CR7HS 7223 CR7HIX 7544 0.7 125 CR3-125 Super Sports 08 DR8EA 7162 DR8EVX 6354 DR8EIX 6681 0.6 JS125Y Tiger 03 DR8ES 5423 DR9EIX 4772 0.7 JSM125 Motard / Trail 10 CR6HSA 2983 CR6HIX 7274 0.6 APRILIA 50 AF1 50 8892 B8ES 2411 BR8EIX 5044 0.5 Amico 50 9294 BR7HS 4122 BR7HIX 7067 0.6 Area 51 (Liquid Cooled 2-Stroke) 98 BR8HS 4322 BR8HIX 7001 0.5 Extrema 50 93 B8ES 2411 BR8EIX 5044 0.5 Gulliver 9799 BR7HS 4122 BR7HIX 7067 0.6 Habana 50, Custom & Retro 9905 BPR8HS 3725 BPR8HIX 6742 0.6 Mojito Custom 50 05 BR9ES 5722 BR9EIX 3981 0.7 MX50 03 BR9ES 5722 BR9EIX 3981 0.7 Rally 50 (Air Cooled) 9599 BR7HS 4122 BR7HIX 7067 0.7 Rally 50 (Liquid Cooled) 9703 BR8HS 4322 BR8HIX 7001 0.5 Red Rose 50 93 B8ES 2411 BR8EIX 5044 0.5 RS 50 (Minarelli engine) 93 B8ES 2411 BR8EIX 5044 0.6 RS 50 0105 BR9ES 5722 BR9EIX 3981 0.7 RS 50 06 BR9ES 5722 BR9EIX 3981 0.5 RS4 50 1113 BR8ES 5422 BR8EIX 5044 0.6 ‡ Early Ducati Testastretta bikes (749, 998, 999 models) can have very little clearance between the plug hex and the RX 50 (Minarelli engine) 97 B9ES 2611 BR9EIX 3981 0.6 cylinder head that may require a thin walled socket, no larger than 20.5mm OD to allow the plug to be fitted. -

Political Art of the Black Panther Party: Cultural Contrasts in the Nineteen Sixties Countermovement

Journal of Undergraduate Research at Minnesota State University, Mankato Volume 9 Article 15 2009 Political Art of the Black Panther Party: Cultural Contrasts in the Nineteen Sixties Countermovement Melissa Seifert Minnesota State University, Mankato Follow this and additional works at: https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/jur Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, and the Modern Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Seifert, Melissa (2009) "Political Art of the Black Panther Party: Cultural Contrasts in the Nineteen Sixties Countermovement," Journal of Undergraduate Research at Minnesota State University, Mankato: Vol. 9 , Article 15. Available at: https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/jur/vol9/iss1/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Research Center at Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Undergraduate Research at Minnesota State University, Mankato by an authorized editor of Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. Seifert: Political Art of the Black Panther Party: Cultural Contrasts in t Political Art of the Black Panther Party: Cultural Contrasts in the Nineteen Sixties Countermovement By: Melissa Seifert The origins of the Black Power Movement can be traced back to the civil rights movement’s sit-ins and freedom rides of the late nineteen fifties which conveyed a new racial consciousness within the black community. The initial forms of popular protest led by Martin Luther King Jr. were generally non-violent. However, by the mid-1960s many blacks were becoming increasingly frustrated with the slow pace and limited extent of progressive change. -

Suspect Until Proven Guilty, a Problematization of State Dossier Systems Via Two Case Studies: the United States and China

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations Fall 2009 Suspect Until Proven Guilty, a Problematization of State Dossier Systems via Two Case Studies: The United States and China Kenneth N. Farrall University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Communication Technology and New Media Commons, International and Intercultural Communication Commons, and the Social Influence and oliticalP Communication Commons Recommended Citation Farrall, Kenneth N., "Suspect Until Proven Guilty, a Problematization of State Dossier Systems via Two Case Studies: The United States and China" (2009). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 51. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/51 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/51 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Suspect Until Proven Guilty, a Problematization of State Dossier Systems via Two Case Studies: The United States and China Abstract This dissertation problematizes the "state dossier system" (SDS): the production and accumulation of personal information on citizen subjects exceeding the reasonable bounds of risk management. SDS - comprising interconnecting subsystems of records and identification - damage individual autonomy and self-determination, impacting not only human rights, but also the viability of the social system. The research, a hybrid of case-study and cross-national comparison, was guided in part by a theoretical model of four primary SDS driving forces: technology, political economy, law and public sentiment. Data sources included government documents, academic texts, investigative journalism, NGO reports and industry white papers. The primary analytical instrument was the juxtaposition of two individual cases: the U.S. -

June 2010 Newsletter

June 2010 – Volume 2, Issue 6 THE DRAGON’S LAIR NEWSLETTER OF THE IRON DRAGON KUNG FU AND KICKBOXING CLUB 91 STATION STREET, UNIT 8, AJAX, ONTARIO L1S 3H2 June 2010 VOLUME 2, ISSUE 6 (905) 427-7370 / [email protected] / www.iron-dragon.ca COMMENTARY As I sit here writing this newsletter in the sweltering heat of an amazing Victoria Day weekend I am overcome by a sense of nostalgia. Can it be that the Bruce Lee film “Enter the Dragon” was released some 37 years ago?!!! It was a trip down memory lane as I prepared the articles related to that film! I will be thrilled if just one of my students discovers this film for the very first time! June 2010 will prove to be a milestone in the competitive aspirations of our club. We have no fewer than 5 competitive events scheduled this month! Our fighter Shawn Nanay will be fighting for an unprecedented 3 times in one month! Our Lil and Young Dragons are competing in the Canada Cup Continuous Sparring Competition and Julian Dias, Chris DiGiovanni and Kevin Lee will be fighting in the Ontario Jiu Jitsu Championships. Competitions in 3 disciplines – Kickboxing , Continuous Fighting and Grappling all in one month!!! We have come a long, long way baby! MARTIAL ARTS IN THE MEDIA “Enter the Dragon” – Bruce Lee’s film masterpiece Enter the Dragon was a groundbreaking film that was released in North America in the summer of 1973, shortly after the death of its star, Bruce Lee. The release of this film was the highlight of the Kung Fu Mania that swept the North American continent in the early 1970’s.