Against Preemption: How Federalism Can Improve the National Legislative Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bernard Magee's Acol Bidding Quiz

Number One Hundred and Fifty June 2015 Bernard Magee’s Acol Bidding Quiz BRIDGEYou are West in the auctions below, playing ‘Standard Acol’ with a weak no-trump (12-14 points) and 4-card majors. 1. Dealer West. Love All. 4. Dealer East. Game All. 7. Dealer North. E/W Game. 10. Dealer East. Love All. ♠ A K 7 6 4 3 2 ♠ 7 6 ♠ A 8 7 ♠ K Q 10 4 3 ♥ 6 N ♥ K 10 3 N ♥ 7 6 5 4 N ♥ 7 6 N W E ♦ K 2 W E ♦ J 5 4 ♦ Q 10 8 6 W E ♦ 5 4 W E S ♣ 7 6 5 S ♣ A Q 7 6 3 ♣ 4 2 S ♣ Q J 10 7 S West North East South West North East South West North East South West North East South ? 1♠ 1NT 1NT Dbl 2♦ 1♥ Pass ? ? 1♠ Pass 1NT Pass ? 2. Dealer East. E/W Game. 5. Dealer East. Game All. 8. Dealer West. E/W Game. 11. Dealer East. Love All. ♠ Q J 3 ♠ 7 6 ♠ A 8 5 3 ♠ 9 8 2 ♥ 7 N ♥ K 10 3 N ♥ A 9 8 7 N ♥ Q J 10 N W E W E W E W E ♦ A K 8 7 6 5 4 ♦ 5 4 ♦ K 6 4 ♦ 8 3 S S S S ♣ A 8 ♣ Q J 7 6 4 3 ♣ A 2 ♣ A 9 6 4 3 West North East South West North East South West North East South West North East South 3♠ Pass 1♠ 1NT 1♥ 1♠ Pass Pass 1♣ Pass ? ? ? 2♣ Pass 2♦ Pass ? 3. -

Saturday, 4/18 Bulletin

Volume 1, Issue 8 April 18, 2015 USBF President Results at the Half... Howie Weinstein USBF Vice President Cheri Bjerkan USBF Secretary & COO Jan Martel TEAM TOTAL 1-15 16-30 31-45 46-60 61-75 USBF CFO Stan Subeck 2 Goldberg 116 30 13 46 27 Director - WUSBC Bernie Gorkin Operations Manager 3 Moss 109 19 42 21 27 Shannon Cappelletti Appeals Administrators Robb Gordon Appeals Committee: Allan Falk The Past Comes Alive Doug Doub Bart Bramley Dutch players Frank van Wezel and Hans van de Konijnenberg Bruce Rogoff both collect books, magazines and Daily Bulletins about Josh Parker bridge. They especially enjoy reading Daily Bulletins from the Danny Sprung pre-internet era because these bulletins are a treasure trove of Peggy Kaplan wonderful photographs, marvellous sketches, splendid deals, Adam Wildavsky and tremendous stories and anecdotes. Howie Weinstein Ron Gerard Steve Robinson Frank and Hans decided that this material should be at the Tom Carmichael disposal of all bridge players. At the same time, they want to save the history of bridge from oblivion. Therefore they VuGraph Organizers launched a free website www.bridgedailybulletins.nl. On this Shannon Cappelletti S BRIDGE CHAMPIONSHIPS site you can find thousands of scanned bulletins, both from Bulletin Editor the digital era and before. They posted WBF, EBL and ACBL Suzi Subeck championship bulletins, as well as many from miscellaneous tournaments around the world. Photographer Peg Kaplan Local Hospitality Chairs And if you have bulletins that they are missing, please contact Barbara -

A Framework for Preemption Analysis

A Framework for Preemption Analysis The decisions of the Supreme Court in cases involving preemption of state law by federal statutes have often produced considerable con- fusion' and criticism. 2 This Note argues that those decisions can be rationalized according to the protection afforded by the state law in question. Laws that protect the people inside state borders from physical injury have received the greatest deference from the Court. Laws that protect the people inside state borders from other dangers have received less deference. State laws that purport to protect people mostly outside state borders have received little deference. Recogni- tion of these categories, as they are set out in this Note, can assist courts as they deal with future preemption cases. I. Categories for Preemption Analysis It is useful to distinguish four possible relationships between na- tional and state laws, which may conveniently be called "express pre- emption," "express saving," "prohibition of dutiful conduct," and "hindrance." Express preemption and express saving are direct rela- tionships between national and state law. Express preemption occurs when a national statute expressly forbids state regulation of a certain type or expressly requires that national regulation be exclusive. Ex- press saving is present when a national statute expressly forbids courts to preempt state laws. Prohibition of dutiful conduct and hindrance are indirect relationships, which involve more complex interactions between state and national law. Prohibition of dutiful conduct is present when state law requires someone to breach duties imposed by national law. Hindrance occurs when state law interferes with op- portunities created by national law, or with the performance of federal duties. -

Preemption Under the Controlled Substances Act Robert A

Journal of Health Care Law and Policy Volume 16 | Issue 1 Article 2 Preemption Under the Controlled Substances Act Robert A. Mikos Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/jhclp Part of the Health Law Commons, Policy Design, Analysis, and Evaluation Commons, Public Policy Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Recommended Citation Robert A. Mikos, Preemption Under the Controlled Substances Act, 16 J. Health Care L. & Pol'y 5 (2013). Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/jhclp/vol16/iss1/2 This Conference is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Health Care Law and Policy by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PREEMPTION UNDER THE CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES ACT ROBERT A. MIKOS States are conducting bold experiments with marijuana law. Since 1996, eighteen states and the District of Columbia have legalized the drug for medical purposes, and two of them have legalized it for recreational purposes as well.1 These states have also promulgated a growing body of civil regulations to replace prohibition. The regulations cover nearly every facet of the marijuana market. Colorado, for example, has adopted more than seventy pages of regulations governing just the distribution of medical marijuana.2 Among many other things, Colorado‘s regulations require medical marijuana vendors to apply for a special Copyright © 2013 by Robert A. Mikos. Professor of Law and Director of the Program in Law & Government, Vanderbilt University Law School. -

Today's Vugraph Matches APBF Bridge Congress on The

Tuesday, August 28, 2012 Editors: Rich Colker, Barry Rigal Bulletin Number 4 Rank Group A VPs Rank Group B VPs Rank Women VPs 1 Beijing Jinghua 63 1 Japan well fitted 57 1 Japan SHIMAMURA 61 2 Pan-China Constr. 56 2 AUSTRALIA KLINGER 55 2 Shenyang Olystar BC 58 3 Beijing BEIH 54 3 SHENZHEN NANGANG 54 3 Japan TAKEUCHI 54 4/5 Japan SAYN 50 4/5 Beijing Dazhong Inv 53 4 Japan Merci 53 4/5 China Geely Auto 50 4/5 CBLT2 53 5 Japan SUGINO 50 6 Japan NON PROBLEM 47 6/7 China H K VICO 52 6 Australia BOURKE 49 7 Japan welcome Kyushu 46 6/7 HYX CHINA 52 7 Japan Naito 47 8 CBLT1 45 8 Japan TANAKA 46 8 Australia WOMEN 36 9 China H K Spark 44 9/10 Japan sacrum 44 9 Japan Misotoma 35 10 Japan City Bridge 43 9/10 Beijing Evertrust 44 10 Japan Evolution 34 11 Japan C'est si bon 42 11 Japan MIURA 37 11 Korea Alpha 27 12/13 Singapore RYLAI 37 12 Korea GLPD 36 12/13 Australia Yarralumla 37 13 Japan Gahhahha H 35 14 Japan KM AT 33 14 Singapore SMJ 34 15 Kuwait 30 15 Japan Papas&Puppies 32 Rank Youth VPs Rank Seniors VPs 1 CHN RDFZ 1 71 1 Japan NOSE 63 2 Shanghai Weiyu BC 65 2 Japan YAMADA 52 3 Beijing Yindi Junior 61 3 Japan Lycaon 50 4 Japan Youth K 53 4 AUSSIES 47 5 CHN RDFZ 2 43 5 MAGIC EYES THAI 46 6 Chinese Taipei Youth 25 6 Chinese Taipei Senior 38 7 Japan Youth A 24 7 China Shanxi elderly 34 8 Japan Youth B 16 8 Japan PSbridge 30 Today’s VuGraph Matches Match 4 (10:00) Match 5 (14:00) Match 6 (16:40) Japan KM AT Australia KLINGER Kuwait vs vs vs Beijing BEIH Japan well fitted CBLT1 Singapore SMJ Beijing Dazhong Investment China Geely Automobile vs vs -

Student Handbook

JOAQUIN ELEMENTARY Joaquin ISD 2017-2018 Student Handbook 1 Joaquin Elementary Mailing address – 11109 Hwy. 84 East, Joaquin, TX 75954 Physical address – 120 Southern Avenue, Joaquin, TX 75954 Fax (936)269-3324 Phone (936)269-3128 Sherry Scruggs, Principal [email protected] ext. 241 Bert Coan, Assistant Principal [email protected] ext. 333 www.joaquinisd.net, school web site Phone Extensions Superintendent’s Office…………………………………………………221 Elementary Office……………………………………………………….321 Food Service Director…………………………………………………...287 Athletic Offices………………………………………………………….428 Band Room……………………………………………………………...427 Maintenance (bus barn)………………………………………………….336 Administration Superintendent………………………………………..…….….Phil Worsham Elementary Principal……………………………………....….Sherry Scruggs Elementary Assistant Principal……………………………….…....Bert Coan Special Education Director………………………….……..Kathy Carrington Transportation Director…………………………………...….Jimmy Jackson Food Service Director……………………………………………Judy Strong Maintenance Director……..……………………………………Mark Bonner Technology Director…………………………………..………Landon Oliver 2 JOAQUIN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL DIRECTORY PK Kathy Brittain [email protected] Aide Kaitlin Lawson [email protected] Aide Julie Bass [email protected] Kindergarten Debbie Barr [email protected] Taylor Fitts [email protected] Aide Joyce Cockrell [email protected] 1st Grade Holly Bonner [email protected] Rachel Bagley [email protected] Shelli Vaughn [email protected] 2nd Grade Deborah Derbonne [email protected] -

Games Are Opened

Editor: Brian Senior • Co-Editor: Ron Klinger Bulletin 1 Layout-Editor: George Georgopoulos Monday, 8 August 2005 GAMES ARE OPENED Her Excellency, Professor Marie Bashir, Governor of New South Wales, being presented with flowers by Brazilian team-member, Paula David The 10th World Youth Team Championship was officially opened by Her Excellency, Professor Marie Bashir, the Governor of the state of New South Wales, at yesterday's Opening Ceremo- ny in the vugraph theatre at the Sydney Showground. Professor Bashir is the first womant to become Governor of New South Wales. She welcomed us all to Sydney and spoke of all the teams as being part of one big family. Professor Bashir also told of her own love for the game of bridge and how she used to play as a student, plus the fact that her Aunt was still an active player at the age of 94 years – truly, bridge is a game for our whole lives. John Wignall, 1st Vice-President of the World Bridge Federation and WBF representative of Zone 7, then officially opened the Championship on behalf of the Zone. Panos Gerontopoulos, WBF Youth Committee Chairman,welcomed all the players and team officials and encouraged everyone to enjoy not only the Championship, but also both Sydney and Australia. Finally, our masters of ceremony, Stefan Back and Kim Neale, introduced each of the teams in turn, to an impressive backdrop of scenes from their countries followed by their photographs. Passport Check Players' passports must be checked by WBF Youth Committee member,Stefan Back, be- fore they play in the Championship. -

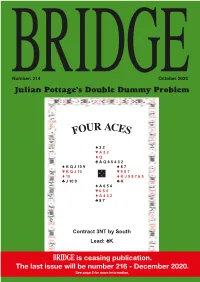

FOUR ACES Could Have Done More Safely

Number: 214 October 2020 BRIDGEJulian Pottage’s Double Dummy Problem UR ACE FO S ♠ 3 2 ♥ A 3 2 ♦ Q ♣ A Q 6 5 4 3 2 ♠ K Q J 10 9 ♠ 8 7 ♥ N ♥ K Q J 10 W E 9 8 7 ♦ 10 S ♦ K J 9 8 7 6 5 ♣ J 10 9 ♣ K ♠ A 6 5 4 ♥ 6 5 4 ♦ A 4 3 2 ♣ 8 7 Contract 3NT by South Lead: ♠K BRIDGE is ceasing publication. The last issueThe will answer be will benumber published on page 216 4 next - month.December 2020. See page 5 for more information. A Sally Brock Looks At Your Slam Bidding Sally’s Slam Clinic Where did we go wrong? Slam of the month Another regular contributor to these Playing standard Acol, South would This month’s hand was sent in by pages, Alex Mathers, sent in the open 2♣, but whatever system was Roger Harris who played it with his following deal which he bid with played it is likely that he would then partner Alan Patel at the Stratford- his partner playing their version of rebid 2NT showing 23-24 points. It is upon-Avon online bridge club. Benjaminised Acol: normal to play the same system after 2♣/2♦ – negative – 2NT as over an opening 2NT, so I was surprised North Dealer South. Game All. Dealer West. Game All. did not use Stayman. In my view the ♠ A 9 4 ♠ J 9 8 correct Acol sequence is: ♥ K 7 6 ♥ A J 10 6 ♦ 2 ♦ K J 7 2 West North East South ♣ A 9 7 6 4 2 ♣ 8 6 Pass Pass Pass 2♣ ♠ Q 10 8 6 3 ♠ J 7 N ♠ Q 4 3 ♠ 10 7 5 2 Pass 2♦ Pass 2NT ♥ Q 9 ♥ 10 8 5 4 2 W E ♥ 7 4 3 N ♥ 9 8 5 2 Pass 3♣ Pass 3♦ ♦ Q J 10 9 5 ♦ K 8 7 3 S W E ♦ 8 5 4 ♦ Q 9 3 Pass 6NT All Pass ♣ 8 ♣ Q 5 S ♣ Q 10 9 4 ♣ J 5 Once South has shown 23 HCP or so, ♠ K 5 2 ♠ A K 6 North knows the values are there for ♥ A J 3 ♥ K Q slam. -

2017 Volume IX No. 14 Federal Preemption and the Bankruptcy Code

Federal Preemption and the Bankruptcy Code: At what Point does State Law Cease to Apply during the Claims Allowance Process? 2017 Volume IX No. 14 Federal Preemption and the Bankruptcy Code: At what Point does State Law Cease to Apply during the Claims Allowance Process? Dylan Lackowitz, J.D. Candidate 2018 Cite as: Federal Preemption and the Bankruptcy Code: At what Point does State Law Cease to Apply during the Claims Allowance Process?, 9 ST. JOHN’S BANKR. RESEARCH LIBR. NO. 14 (2017). Introduction Anything you do in bankruptcy can and will be used against you in bankruptcy. Prior to the commencement of a bankruptcy case, perhaps courts should issue this Miranda-esque warning to the parties. At least, if the bankruptcy court had, Plymouth LLC (“Plymouth”) might have saved approximately $800,000 that it spent acquiring a lien against Princeton LP’s (“Princeton”) vacant office park in the Township of Lawrence, New Jersey.1 Recently, the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit held that Plymouth’s claim against Princeton in Princeton’s bankruptcy case was disallowed for violating New Jersey’s tax sale law pursuant to section 502(b)(1) of the United States Bankruptcy Code (the “Code”).2 There, Plymouth unsuccessfully argued that the claims allowance process in bankruptcy preempted New Jersey’s tax sale law.3 As this case illustrates, the application of the preemption doctrine in bankruptcy can have a dramatic effect on the outcome of a bankruptcy case. A court’s decision regarding the applicability of preemption in the claims allowance context can mean the difference between a creditor receiving the total value of their claim, or nothing at all. -

Federal Preemption of State Tort Claims

The Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law CUA Law Scholarship Repository Scholarly Articles and Other Contributions Faculty Scholarship 2001 Federal Preemption of State Tort Claims Marin Roger Scordato The Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/scholar Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, State and Local Government Law Commons, and the Torts Commons Recommended Citation Marin Roger Scordato, Federal Preemption of State Tort Claims, 35 U.C. DAVIS L. REV. 1 (2001). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarly Articles and Other Contributions by an authorized administrator of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. .I University of California U.C. DAVIS LAW REVIEW ' / Davis VOLUME 35 NOVEMBER 2001 NUMBER 1 Federal Preemption of State Tort Claims Marin R. Scordato TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................2 I. INTRODUCTION TO FEDERAL PREEMPTION ........................................9 A. Sources of FederalPreemption ....................................................9 B. Categories of Federal Preemption .............................................11 II. GEIER V. AMERICAN HONDA MOTOR COMPANY ................. 14 III. APPROACHES TO PREEMPTION JURISPRUDENCE ...............................20 A. -

Federal Preemption, the FDA, and Prescription Drugs After Wyeth V

Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy Volume 25 Issue 2 Symposium On Health Care: Health, Ethics, & Article 19 the Law January 2014 The Other War on Drugs: Federal Preemption, the FDA, and Prescription Drugs after Wyeth v. Levine Joseph F. Petros III Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndjlepp Recommended Citation Joseph F. Petros III, The Other War on Drugs: Federal Preemption, the FDA, and Prescription Drugs after Wyeth v. Levine, 25 Notre Dame J.L. Ethics & Pub. Pol'y 637 (2012). Available at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndjlepp/vol25/iss2/19 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTES THE OTHER WAR ON DRUGS: FEDERAL PREEMPTION, THE FDA, AND PRESCRIPTION DRUGS AFTER WYETH V. LEVINE JOSEPH F. PETROS 111* INTRODUCTION Amidst the debates over health care reform in the United States, there are several common desires that most Americans share: lower costs, greater availability, and continued innovation. Yet as Americans have fixed their attentions on reform legisla- tion, few outside academia have noticed a recent and potent blow to these desires in one of the major sectors of the health care industry. This is, perhaps, because the blow came from the "least dangerous"' branch of the federal government. The case was Wyeth v. Levine,2 and the issue was the doctrine of federal preemption as it applies to the regulation of prescription drug warning labels by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). -

Conjosé Restaurant Guide the 60Th World Science Fiction Convention

ConJosé Restaurant Guide The 60th World Science Fiction Convention McEnery Convention Center San José, California Codes Used in this Guide Distance: Amounts: A Short walk $ Cheap B Walking distance $$ Reasonable C Car required $$$ Expensive D Long car ride $$$$ Very expensive E In another city Codes: B Breakfast NCC No Credit Cards BW Beer & Wine Only NR No Reservations D Dinner OS Outdoor Seating DL Delivers PP Pay Parking FB Full Bar R Romantic FP Free Parking RE Reservations Essential GG Good for Groups RL Reservations Recommended IWL Impressive Wine List for Large Parties KF Kid Friendly RR Reservations Recommended L Lunch SF Smoke Free TO Take Out LL Open Late (11:00 PM) TOO Take Out Only LLL Open Very Late (12:30 AM) LM Live Music VP Valet Parking ConJosé Restaurant Guide The 60th World Science Fiction Convention 29 August through 2 September 2002 McEnery Convention Center San José, California Karen Cooper & Bruce Schneier Restaurant Guide Reviews by Karen Cooper and Bruce Schneier Cover Art: David Cherry Copyediting & Proofreading: Beth Friedman Layout & Design: Mary Cooper © 2002 San Francisco Science Fiction Conventions, Inc., with applicable rights reverting to creators upon publication. “Worldcon,” “World Science Fiction Convention,” “WSFS,” “World Science Fiction Society, “NASFIC,” and “Hugo Award” are registered service marks of the World Science Fiction Society, an unincorporated literary society. ConJosé is a service mark of San Francisco Science Fiction Conventions, Inc. Table of Contents Welcome ......................................................................................................7