Blue of Knowledge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

D and Work Plentiful in Java the East Sy Manufacturing Company

Vol.9 September, 19 2 2 *o.i Our Front Cover and Center Pases EAVING in September of 1921 Mr. and Mrs. Frederick in Java. The pictures and the copy on the center pages Shedd and their two daughters, Marion and Elizabeth, were also contributed by Mr. Shedd, most of the copy being L started on a tour around the globe, which was not taken from letters which he had sent to members of his completed until June of 1922. They visited France, Italy family and friends. We have not had a more interesting and the European countries, then Egypt, Burma, India, center-page spread. Mr. Shedd is one of the directors of the Ceylon, Straits Settlement. Java, China and Japan. Jeffrey Mfg. Co., and has always shown a keen appreciation The picture on the front cover is of a plantation scene ot our employees' publication. KEYBOARD KLIPPINGS A HEART BREAKER—LOST IN THE 10th INNING since their move to the gallc By Poll'janna Wigginton Jeffrey Team Occupies Second Place in League to become a part of Dcpt. 9. One of our girls recently had Ten innings of good baseball were required to decide the cham Mr .Bierly is- back again a letter for a Coal Company in pionship in the Industrial Twilight League when the American Rail looking fine after his vacation. 'est Vriginia for the attention way Express team played our Jeffrey team on Saturday, August Uda Schall spent part of 1 Mr. "Beans," Secretary, and 12th, on the Northwood diamonds. The boys played a hard game vacation at Indian Lake, Oh e noticed another executive of but they finally lost by a score of 5 to 4. -

Nowyes632475.Pdf

Published by PEACHTREE PUBLISHING COMPANY INC. 1700 Chattahoochee Avenue Atlanta, Georgia 30318-2112 www.peachtree-online.com Text © 2021 by Bill Harley Cover and interior illustrations © by Pierre-Emmanuel Lyet All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. Edited by Vicky Holifield Cover design by Kate Gartner Interior design and composition by Adela Pons Printed in February 2021 by LSC Communications in Harrisonburg, VA in the United States of America. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 First Edition ISBN 978-1-68263-247-5 Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress. BILL H ARLEY To Debbie Block in all ways, always —B. H. Chapter ONE “The barbecue ones,” Conor says. “I know,” Mari says for the fourth time. “I don’t like the other ones. Especially not the vinegar ones. They’re bad.” Conor is standing sideways to the rows of snacks, facing the aisle that leads away from the meat section. His head is down—he’s not looking at her. He never looks at her. He’s not looking at anything except his fingers, which are opening and closing like they’re on the inside of a puppet and the puppet is talking. But the puppet is silent. It’s the motion of the hand that fascinates him, that has always fascinated him. -

Medeski Martin & Wood Last Chance to Dance Trance

Medeski Martin & Wood Last Chance To Dance Trance (Perhaps) Best Of (1991-1996) mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Jazz Album: Last Chance To Dance Trance (Perhaps) Best Of (1991-1996) Country: Canada Released: 1999 Style: Breakbeat, Jazz-Rock, Future Jazz, Drum n Bass MP3 version RAR size: 1859 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1238 mb WMA version RAR size: 1713 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 516 Other Formats: AA MP3 DMF MP2 WAV APE MP1 Tracklist Hide Credits Chubb Sub Edited By – Bob WardEdited By [With] – Bob WardMastered By – Dr. Toby 1 5:21 Mountain*Producer – David Baker, Jim Payne, MMW*Recorded By – David BakerWritten-By – Medeski Martin & Wood Bubblehouse Engineer [Assistant] – Carl Green, Mark KindermanEngineer [Recording] – David 2 4:28 BakerExecutive Producer – Hans WendlMastered By – Dr. Toby Mountain*Mixed By [With] – David Baker, Katsu NaitoProducer – db*, MMW*Written-By – MMW* Last Chance To Dance Trance (Perhaps) 3 Edited By – Bob WardMastered By – Dr. Toby Mountain*Producer – David Baker, Jim 7:38 Payne, MMW*Recorded By – David BakerWritten-By – Medeski Martin & Wood Hermeto's Daydream Edited By – Bob WardMastered By – Bob AppelMixed By – David Baker, John SiketRecorded 4 7:11 By [Baby Monster] – David BakerRecorded By [Water Music] – Roger TeltzmanWritten-By – Billy Martin, John Medeski Is There Anybody Here That Love My Jesus Arranged By – MMW*Edited By [With] – Bob WardEngineer [Assistant] – Carl Green, Mark 5 KindermanEngineer [Recording] – David BakerExecutive Producer – Hans WendlMastered 4:26 By – Dr. Toby Mountain*Mixed By [With] – David Baker, Katsu NaitoProducer – db*, MMW*Written-By – Traditional The Lover 6 Edited By – Bob WardMastered By – Dr. -

MAY BE ONE MORE. Clubs

TRADEMARKS!) BY THE SPORTINO LIFE PtTB. CO. ENTERED AT PHILA. P. O. AS SECOND CLASS MATTER VOLUME 26, NO. 7. PHILADELPHIA, NOVEMBER 9, 1895. PRICE, TEN CENTS. TRANSFERRING BALL PLAYERS. A REGULAR BILL NYE. Minor League Men Put Into the Big Such Appears to be Scrappy Joyce MAY BE ONE MORE. Clubs. of the Washingtons. Washington, D. C., Nov. 3. Nick E. As a base ball player, Billy Joyce, the A NEW CALIFORNIA LEAGUE FOR Young, president and secretary of the Senator's third baseman, does not need an BALL LEAGUE BEING National Base Ball League, is engaged in introduction, but unless, the "Washington ANOTHER negotiating the transfer of a number of Post" has given credit where it is not due. NEXT SEASON. minor league players to the clubs of the Scrappy is a regular Bill Nye. He is sup FIGURED ON. National League, under the rules per posed to have written the following gem; mitting this to be done upon the payment "I am back in St. Louis again. Some one in of $500 to the minor club as soon as the player Washington sent me the "Post," which says Six Cities, With San Francisco as a signs a League cor tract. The list of men thus I am looking for a political job. I am looking A New Tri-State Organization With far drafted for the season of 1896 include tbt for it, but 1 guess I will be cross-eyed before I following: find it. Alderman Cronin says he can get me a Central Point, Will Compose the Hulen, of Minneapolis, with Philadelphia: Yor- job on the police force, but I decline. -

XENIA and Other Classics

XENIA and other classics by CAROLINE HENLEY M.S. in Applied Analytics, Columbia University, 2018 B.A. in American History and Classical Studies, University of Pennsylvania, 2007 A CREATIVE THESIS submitted to Southern New Hampshire University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing School of Liberal Arts October 17, 2020 This thesis has been examined and approved. _____________________________________ Faculty name Thesis Director ______________________________________ Second reader Faculty name 2 XENIA and other classics Spring Breakers … 3 Middle School Adventure A … 18 Dog Taxi … 35 Country Club … 53 Last Day … 67 Josie, the Wrath of God … 73 Who Else Is Coming to the House? … 93 That’s Halifax … 111 Xenia … 123 3 SPRING BREAKERS Allison stooped with her knee to the ground, studying the earliest coins displayed, silver and bulky at three inches wide. The relief of a gorgon stared back from behind the glass, tongue out, teeth bared, the circular edges of the coin stretched so much like Play-Doh she imagined the Greeks entrusting its minting to a child. She stood back up and was startled by a tall red-haired young man hovering over her. She knew his face from the opposite end of a scratched-up wooden table on the ground floor of Logan Hall. He apologized, but lingered as if they were already in the midst of a conversation. He explained that drachmae were made of electrum, an alloy of silver and gold, but only made with a wee bit of gold once circulated under the Roman Empire. -

DROP ME in the WATER a Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty

DROP ME IN THE WATER A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Fine Arts Tara Kaloz May, 2011 DROP ME IN THE WATER Tara Kaloz Thesis Approved: Accepted: _________________________ _________________________ Advisor Dean of the College Imad Rahman Dr. Chand Midha _________________________ _________________________ Committee Member Dean of the Graduate School Eric Wasserman Dr. George R. Newkome _________________________ _________________________ Committee Member Date Robert Pope ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER PROLOGUE. CARRIE ANNE (AFTERLIFE) . iv I. OLSON . 1 II. GEORGE . 20 III. CARRIE ANNE . 43 IV. TOMMY . .64 V. OLSON . 82 VI. DANI . 102 VII. JOE . 116 VIII. OLSON . .. .135 iii PROLOGUE CARRIE ANNE (AFTERLIFE) The water takes me in like breath and I resonate with the saturated inhale-exhale, exist as a hiccup that chokes out the lungs, drowns them. Foam lines the banks of the river, laps at the root systems of trees like the spittle that lines the mouths of newborns and the lips of seizure victims. I am the fragment that gets stuck in the throat, but the whole process lacks the constriction. Instead, I am snuffed, deprived of oxygen until the ability to glow gets extinguished. Then there's just the wick. The charred-up stick figure remains of what was once a viable vessel. I'm naked. Leaves press themselves slick against my skin. They stick close to my humilities, yet never provide sufficient enough cover. Fact is, I don't care. I don't question how I came to be clothes-less, who did the undressing. -

20210824 Recensieoverzichtplaten69tmheden

ARTIEST PLAAT LABEL RECENSENT NR. 1000+1 Butterfly Garden El Negocito Fluitman 224 3 Brave Souls 3 Brave Souls Challenge Korten 191 3/4 Peace 3/4 Peace El Negocito Loo, te 207 3/4 Peace Rainy Days On The Common Land El Negocito Loo, te 250 37 Fern 37 Fern TryTone Loo, te 348 3Hands Clapping Shaman Dance Juice Junk Records Korten 99 3times7 Squeeze The Lemon Eigen Beheer Hollebrandse 281 4Beat6 Plays The Music Of Benny Goodman Vol. 1 Eigen Beheer Lammen 85 4tet Different Song Leo Records Loo, te 178 5 Up High 5 Up High Timeless Fluitman 273 6 Spoons, 1 Kitchen Blend LopLop Beetz 201 6ix Almost Even Further Leo Records Loo, te 187 A A.G.N.Z. (Azzolina, Govoni, Nussbaum & Zinno) Chance Meeting Whaling City Sound Fluitman 264 Aagre, Froy Cycle Of Silence ACT Fluitman 133 Aardvark Jazz Orchestra American Agonistes Leo Records Loo, te 100 Aardvark Jazz Orchestra Evocations Leo Records Loo, te 181 Aardvark Jazz Orchestra Impressions Leo Records Loo, te 226 Abate, Greg Magic Dance Whaling City Sound Valk, de 353 Abate, Greg & Phil Woods Kindred Spirits Live At Chan's Whaling City Sound Fluitman 257 Abate, Greg & Tim Ray Trio Road To Forever Whaling City Sound Fluitman 274 Abdelnour/Schild La Louve Wide Ear Loo, te 322 Abercrombie Quartet, John Wait Till You See Her ECM Korten 128 Abercrombie Quartet, John Within A Song ECM Korten 183 Abercrombie Quartet, John 39 Steps ECM Beetz 209 Abercrombie, John The Third Quartet ECM Korten 76 Abercrombie, John & John Ruocco Topics Challenge Fluitman 90 Ablanedo, Pablo ReContraDoble Creative Nation Music Fluitman 197 Abou-Khalil, Rabih Em Português Enja Loo, te 101 Abou-Khalil, Rabih Selection Enja Loo, te 131 Abou-Khalil, Rabih Trouble In Jerusalem Enja Loo, te 150 Abrams, Jess Growing Up Challenge Huser 93 Abrams, Muhal Richard Sound Dance Pi Recordings Loo, te 161 Absolute Ensemble (ft. -

'Scofield's Probing, Groove-Infused Licks and MMW's Future-Funk

NOVEMBER 2011 ISSUE MMUSICMAG.COM REVIEWS HOLE MNobody’sEDESKI, DaughterSCOFIELD, MARTIN & WOOD [Universal] Live: In Case the World Changes Its Mind [Indirecto] The first album released under the Hole moniker since 1998’s Celebrity Skin is really frontwoman Courtney Love’sMedeski, Martin & Wood, who’ve been redefining the jazz keyboard trio second solo album—co-founder,for a remarkable two decades now, first collaborated with guitar dynamo songwriter and lead guitarist Eric Erlandson isn’t involved,John Scofield in 1997 on the latter’s A Go Go album. Even then the match nor is any other previous Hole member. So it’s Love andwas three ideal: Scofield’s probing, groove-infused licks and MMW’s future-funk ringers on 11 new songs—10 of which Love wroteworship with made one another whole. Nearly a decade later, MSMW made its collaborators like Billy Corgan,official Linda debut Perry as and a newstandalone (if sporadic) unit when Scofield linked with guitarist Micko Larkin. (Perry gets full credit on one tune, “Letter to God.”) keyboardist John Medeski, bassist Chris Wood and drummer Billy Martin on Much of the riveting intensity of the group’s 1990s heyday appears to havetheir left 2006along with Out her Louder former andDaniel Jackson subsequent tour. In Case the World Changes bandmates, but there are fl ashes here of the snarling Too often, though, the slower songs trip her up. While once fury Love deployed to suchIts devastatingMind was effect culled back from in the those day. theylive weredates, showcases and not for unexpectedly—MMWharrowing displays of naked emotion,are She spits out her vocals lovedwith vengeful by the disdain jam-band on “Skinny crowd Little asLove well sounds as morejazzers—there’s dispassionate thesea whole days. -

The Unguarded House

First}.. thlished r9r7 Set in ten point Bas\ •rville one point leaded and J*i(ltedl i.n Great Britain b.JI Taylor Garnett Evans- & Co . .k!d Watrord, H�rifordshire WHEN his mother !lift the electric fa n running at pight, it kept him awake, although the rubber blades made only a very slight noise: a flapping whirr and sometimes a click wben the curtains �t C'\j-lght in tie blades. Then Mother got up, swearing softly to he�lf, pulled the curtains out of the fa n and pinned them between the doors of the bookcase. Mother's bedside lamp ll!.d a green silk shade-a watery gree'n, flecked with yellow-and the glass of red wine standing on the night-table looked as though � were ink, a dark slow pois� which Mother drank in small sips. Sh�ead and smoked and occasionally took a sip of wine. Lying as still as a mouse, so that she would pa)lno attention to him, he watched her through half-closed lids and fo llowed the cigarette smoke as it rose to the fa n: white and grey layers of smoke which were sucked up, absorbed and spewed out by the soft green rubbe�b.la:tts. The fa n was nearly as large as those in th6\�i.uehouses; it had a peaceful drone and cleansed the air in the room within a few minutes. Then Mother pressed the button on the wall near her bed, not fa r fr om where hung the picture of Father-a young, smiling man with a pipe in his mouth, fa r too young to be the fa ther of an eleven-year-old boy. -

Chick Corea, Cassandra Wilson, Bill Frisell and More

Headliners revealed for Copenhagen Jazz Festival 2013, July 5-14 - Chick Corea, Cassandra Wilson, Bill Frisell and more Copenhagen Jazz Festival has revealed this year's festival poster and named the first batch of the headliners that will be performing this July. Already the outlines of the 35th edition of Copenhagen’s huge annual music celebration of all sorts of jazz, world, funk, avant-garde and a lot more are beginning to form. Copenhagen’s unique jazz history is a key factor in the exceptionally high artistic level of the Copenhagen Jazz Festival, something that can be experienced at the historic jazz venues, theaters and many free open- air stages strategically located throughout the city. Together with Copenhagen’s record number of cafés and other venues, these stages create a unique atmosphere, bringing the city alive with jazz from early morning to late at night. People don’t only come for a fantastic musical experience, but for the unique atmosphere throughout Copenhagen when jazz for ten days every year takes over the culture- and family-friendly city. First headliners ready for Copenhagen Jazz Festival 2013: - Chick Corea and the Vigil (US) - Cassandra Wilson (US) - Medeski Martin & Wood (US) - David Murray Infinity Quartet feat. Macy Gray (US) - Bill Frisell & The Big Sur Sextet (US) - Marcus Miller (US) - Charles Lloyd, Zakir Hussein & Eric Harland (US/IN) - Branford Marsalis (US) - Laura Mvula (UK) This year's festival poster is made by painter and street artist Søren Behncke Friday April 19th the festival unveiled this year’s festival poster at a combined poster release party and concert at Statens Museum for Kunst. -

Portland Daily Press

PORTLAND DAILY PRESS. Established, June 23, 1862. Vol. 6. PORTLAND, SATURDA Y MORNING, JUNE 29, 1867, Terms Eight Dollarsper annum, in advance* ___ — -___ _ w*—^_ REMOVALS. THE PORTLAND DAILY PRESS is published BUSINESS CAKUM. MISCELLANEOUS. lASEIUANCfc The Ckampugne District. ev-rytlay, at No. I Printers’ (Sunday excepted,i Robert Tomes Exchange, Comma rial Street, Portland. has written a book entitled R DAILY PRESS. N. A. FOSTER, PROPRIETOR. BKABBUliY* BR1DBCBY. the E MOV AL. INSURANCE NOTICE. “The Champagne Country.” Mr. Tomes was 'Ihkms: —Eight Dollar!' a year in advance* PORTLAND. consular agent of the United States in uu \ Counsellors at W. D. LITTLE & CO„ ancient city of Sheims, the chief commercial THE MAINE STATE PRESS,is published at the Lair, BENEFIT a MUTUAL removed their Insurance and Katlwav FOYE, COFFIN & centre of the district. This dis- Same place every Thursday morning at $-.00 year. linn It SWAN, M Champagne Having* Vuildiug, Excbaafic Si, HAVETicket 01)1 res tYom Commercial Slrect and Mai- Saturi*/ mine;, June 29, 18o7. Invariably in advance. trict is remote from the usual lines of Amerk Biou Bradbury, J ket Square, to their new office in the Deerlng Block, UNDEBWKITEKS, of inch of A. Life Insurance —AND— but its famous wine attracts for- Rates advertising.—One space,tn W. Bradbury, j PORTLAND. Company, uYo. can travel, length oi June 27-dtt 40 1-2 Exchange column, coii.MiiuteP a •■square." Street, as all want to the arti- : 76 NOMINATION. eign tourists, try pure 'V1 5<» per square daily IIwt week cents per 1ST. J. Second over store of William D. -

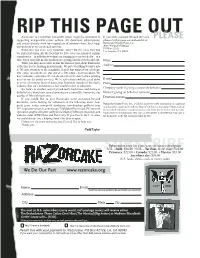

Read Razorcake Issue #48 As a PDF

RIP THIS PAGE OUT Razorcake LV D ERQD¿GH QRQSUR¿W PXVLF PDJD]LQH GHGLFDWHG WR If you wish to donate through the mail, PLEASE supporting independent music culture. All donations, subscriptions, please rip this page out and send it to: and orders directly from us—regardless of amount—have been large Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc. components to our continued survival. $WWQ1RQSUR¿W0DQDJHU PO Box 42129 Razorcake has been very fortunate. Why? By the mere fact that Los Angeles, CA 90042 we still exist today. By the fact that we have over one hundred regular contributors—in addition to volunteers coming in every week day—at a time when our print media brethren are getting knocked down and out. Name What you may not realize is that the fanciest part about Razorcake is the zine you’re holding in your hands. We put everything we have into Address it. We pay attention to the pragmatic details that support our ideology. Our entire operations are run out of a 500 square foot basement. We don’t outsource any labor we can do ourselves (we don’t own a printing press or run the postal service). We’re self-reliant and take great pains E-mail WRFRYHUDERRPLQJIRUPRIPXVLFWKDWÀRXULVKHVRXWVLGHRIWKHPXVLF Phone industry, that isn’t locked into a fair weather scene or subgenre. Company name if giving a corporate donation 6RKHUH¶VWRDQRWKHU\HDURIJULWWHGWHHWKKLJK¿YHVDQGVWDULQJDW disbelief at a brand new record spinning on a turntable, improving our Name if giving on behalf of someone quality of life with each spin. Donation amount If you would like to give Razorcake some