XENIA and Other Classics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

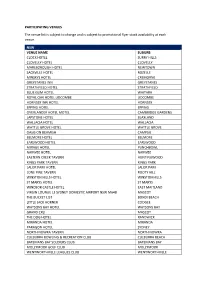

PARTICIPATING VENUES the Venue List Is Subject to Change and Is

PARTICIPATING VENUES The venue list is subject to change and is subject to promotional flyer stock availability at each venue. NSW VENUE NAME SUBURB CLOCK HOTEL SURRY HILLS CLOVELLY HOTEL CLOVELLY MARLBOROUGH HOTEL NEWTOWN SACKVILLE HOTEL ROZELLE MINSKYS HOTEL CREMORNE GREYSTANES INN GREYSTANES STRATHFIELD HOTEL STRATHFIELD BLUE GUM HOTEL WAITARA ROYAL OAK HOTEL LIDCOMBE LIDCOMBE HORNSBY INN HOTEL HORNSBY EPPING HOTEL EPPING OVERLANDER HOTEL MOTEL CAMBRIDGE GARDENS LAPSTONE HOTEL BLAXLAND WALLACIA HOTEL WALLACIA WATTLE GROVE HOTEL WATTLE GROVE OASIS ON BEAMISH CAMPSIE BELMORE HOTEL BELMORE EARLWOOD HOTEL EARLWOOD MIRAGE HOTEL PUNCHBOWL NARWEE HOTEL NARWEE EASTERN CREEK TAVERN HUNTINGWOOD KINGS PARK TAVERN KINGS PARK LALOR PARK HOTEL LALOR PARK LONE PINE TAVERN ROOTY HILL WINSTON HILLS HOTEL WINSTON HILLS ST MARYS HOTEL ST MARYS WINDSOR CASTLE HOTEL EAST MAITLAND VIRGIN LOUNGE L3 SYDNEY DOMESTIC AIRPORT NSW M648 MASCOT THE BUCKET LIST BONDI BEACH LITTLE JACK HORNER COOGEE WATSONS BAY HOTEL WATSONS BAY GRAND CRU MASCOT THE DOG HOTEL RANDWICK MIRANDA HOTEL MIRANDA PARAGON HOTEL SYDNEY NORTH NOWRA TAVERN NORTH NOWRA CULBURRA BOWLING & RECREATION CLUB CULBURRA BEACH BATEMANS BAY SOLDIERS CLUB BATEMANS BAY MOLLYMOOK GOLF CLUB MOLLYMOOK WENTWORTHVILLE LEAGUES CLUB WENTWORTHVILLE BLACKTOWN WORKERS CLUB BLACKTOWN ROOTY HILL RSL CLUB ROOTY HILL ST MARYS RUGBY LEAGUE CLUB ST MARYS ST JOHNS PARK BOWLING CLUB LTD ST JOHNS PARK CASTLE HILL RSL CLUB CASTLE HILL MORUYA BOWLING & REC CLUB LTD MORUYA COBARGO HOTEL COBARGO CRONULLA RSL MEMORIAL CLUB CRONULLA -

Westside Seattle 7-7-17

FRIDAY, JULY 7, 2017 | Vol. 99, No. 27 Westside Seattle Your neighborhood weekly serving Ballard, Burien/Highline, SeaTac, Des Moines, West Seattle and White Center SUMMER IS FINALLY HERE GET OUTSIDE!See West Seattle Summer Fest Schedule » P. 11 Photo by Kimberly Robinson Photos by Patrick Robinson See our listings on page 14 4700 42nd S.W. • 206-932-4500 • BHHSNWRealEstate.com © 2017 HSF Aliates LLC. 2 FRIDAY, JULY 7, 2017 WESTSIDE SEATTLE FRIDAY, JULY 7, 2017 | Vol. 99, No. 27 Borderlines (revisited) Editor’s note: Here is an offering by last Saturday and quoth, “The kids have and on arriving he organized us into a Lee Robinson, who my four brothers and I been bugging me to take them fishing work crew. While we were spreading called Mom, from one of her periodic col- Sunday and I don’t really want to go my- out camp in a lovely gravel pit, he dis- umns. This one from Aug. 15, 1962. There self but you know how it is. They’re little appeared, as was to be expected. But was a family rumor that Mom often wrote for such a short time.” we didn’t mind, we had food, the sun Ballard News-Tribune, Highline Times, West Seattle Herald, Dad’s weekly column, Borderlines, after he We have heard this blarney so often we was shining, the river rippled peaceful- Des Moines News, SeaTac News, White Center News fell asleep in the chair when he had typed a just went about our duties and said noth- ly and all was right with the world for single word, then groggily schlepped off to ing. -

Blaze Damages Ceramic Building

• ev1e Voi.106No.59 University of Delaware, Newqrk. DE Financial aid expecte to be awarded in July By BARBARA ROWLAND To deal with the budgetary The Office of Financial Aid impasse, the university's is anticipating a "bottleneck" financial aid office will send in processing Guaranteed out estimated and unofficial Student Loans (GSLs) as soon award notices on the basis as the federal budget is pass- that the prog19ms will re- ed by-Congr.ess. main the same'-- Because Lhe==amount-oL __- M_ac!)_o_!!ald does 11:0t expect federal funding for both Pell to receive an indication on the Grants and the GSL program amount of. f~ding for Pell has not yet been determined Grants untll this July. the university has not bee~ In an effort to alleviate the - able to award financial aid pressure students may feel packages, according to Direc- -about tuition payments, Mac tor of Financial Aid Douglas Donald said the university MacDonald. will allow students to pay their tuition a quarter at a MacDonald emphasized the time, instead of a half and problem of funding student half installment plan. assistance is not as serious as The university has the problem with delivering also established a $50,000 aid in time for the fall scholarship progr.ani to semester. award students on the basis of MacDonald believes it is both merit and need. unlikely Congress will imple Some of tne changes the ment any changes in the two financial aid office has pro , . _ . Review Photo by Leigh Clifton programs in 1982-83 because jected for next year include: FIREMEN' RESPOND TO A BLAZE at the university's cer'amic building Wednesday night which of the late date. -

February 2017

城市漫步上海 英文版 2 月份 国内统一刊号: CN 11-5233/GO China Intercontinental Press FEBRUARY 2017 that’s Shanghai 《城市漫步》上海版 英文月刊 主管单位 : 中华人民共和国国务院新闻办公室 Supervised by the State Council Information Office of the People's Republic of China 主办单位 : 五洲传播出版社 地址 : 中国北京 北京西城月坛北街 26 号恒华国际商务中心南楼 11 层文化交流中心 邮编 100045 Published by China Intercontinental Press Address: 11th Floor South Building, HengHua linternational Business Center, 26 Yuetan North Street, Xicheng District, Beijing 100045, PRC http://www.cicc.org.cn 总编辑 Editor in Chief of China Intercontinental Press: 慈爱民 Ci Aimin 期刊部负责人 Supervisor of Magazine Department: 邓锦辉 Deng Jinhui 主编 Executive Editor: 袁保安 Yuan Baoan 编辑 Editor: 王妍霖 Wang Yanlin 发行 / 市场 Circulation/Marketing: 黄静 Huang Jing, 李若琳 Li Ruolin 广告 Advertising: 林煜宸 Lin Yuchen Chief Editor Dominic Ngai Section Editors Andrew Chin, Betty Richardson, Alyssa Wieting Senior Editor Tongfei Zhang Events Editor Zoey Zha Production Manager Ivy Zhang Designer Joan Dai, Aries Ji Contributors Mario Grey, Mia Li, Ian Walker, Timothy Parent, Logan Brouse, Tristin Zhang, Sky Thomas Gidge, Amy Fabris-Shi, Catherine Lee, Jonty Dixon, Dr Daniel Meng Copy Editor Frances Arnold HK FOCUS MEDIA Shanghai (Head office) 上海和舟广告有限公司 上海市蒙自路 169 号智造局 2 号楼 305-306 室 邮政编码 : 200023 Room 305-306, Building 2, No.169 Mengzi Lu, Shanghai 200023 电话 : 021-8023 2199 传真 : 021-8023 2190 Guangzhou 上海和舟广告有限公司广州分公司 广州市越秀区麓苑路 42 号大院 2 号楼 610 室 邮政编码 : 510095 Room 610, No. 2 Building, Area 42, Luyuan Lu, Yuexiu District, Guangzhou 510095 电话 : 020-8358 6125, 传真 : 020-8357 3859-800 Shenzhen 广告代理 : -

D and Work Plentiful in Java the East Sy Manufacturing Company

Vol.9 September, 19 2 2 *o.i Our Front Cover and Center Pases EAVING in September of 1921 Mr. and Mrs. Frederick in Java. The pictures and the copy on the center pages Shedd and their two daughters, Marion and Elizabeth, were also contributed by Mr. Shedd, most of the copy being L started on a tour around the globe, which was not taken from letters which he had sent to members of his completed until June of 1922. They visited France, Italy family and friends. We have not had a more interesting and the European countries, then Egypt, Burma, India, center-page spread. Mr. Shedd is one of the directors of the Ceylon, Straits Settlement. Java, China and Japan. Jeffrey Mfg. Co., and has always shown a keen appreciation The picture on the front cover is of a plantation scene ot our employees' publication. KEYBOARD KLIPPINGS A HEART BREAKER—LOST IN THE 10th INNING since their move to the gallc By Poll'janna Wigginton Jeffrey Team Occupies Second Place in League to become a part of Dcpt. 9. One of our girls recently had Ten innings of good baseball were required to decide the cham Mr .Bierly is- back again a letter for a Coal Company in pionship in the Industrial Twilight League when the American Rail looking fine after his vacation. 'est Vriginia for the attention way Express team played our Jeffrey team on Saturday, August Uda Schall spent part of 1 Mr. "Beans," Secretary, and 12th, on the Northwood diamonds. The boys played a hard game vacation at Indian Lake, Oh e noticed another executive of but they finally lost by a score of 5 to 4. -

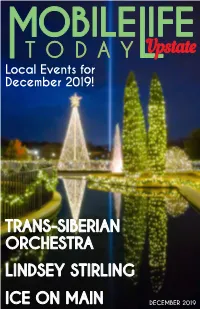

Mobilelife Today

T O D A Y Local Events for December 2019! TRANS-SIBERIAN ORCHESTRA LINDSEY STIRLING ICE ON MAIN DECEMBER 2019 CONTENTS LOCAL EVENTS Arts & Cultural Events 2-3 5 Concerts 3-4 Food Events 4 Festivals & Fairs 5-6 Sports 6 Other Events 7 New Year’s Eve Events 7-8 Recurring Events 9 6 ACTIVITIES FOR KIDS Just for Fun 10-11 SPEEDWAY Drop-Off Events 11 CHRISTMAS DAY TRIPS 12 PUBLISHER David Nichols 12 EDITOR Katie Nichols DESIGNER Kelly Vervaet COVER PHOTO Derek Eckenroth Bob Jones University Christmas Lights 5 LINDSEY Sales and freelance writer opportunities are STIRLING available. Send inquiries to: [email protected] If you would like your business featured in MobileLife Today Upstate, 4 please contact us at: [email protected] If you would like your event featured, please contact: [email protected] Comments and suggestions are always 3 welcome at: ©2019, All Rights Reserved [email protected] Reproduction without permission is prohibited MobileLife Today is published by 1 upstate.mobilelifetoday.com ModernLife publishing LOCAL EVENTS Arts & Cultural Events ArtBreak: Illuminations A Holly Jolly Christmas Date/Time: Dec. 12th, 12pm Date/Time: Dec. 5th-21st, Various Times Location: Applied Studies Building Location: Centre Stage Bob Jones University Cost: $23.50-$36.50 Cost: $10 for lunch and lecture Description: “Have a cup of cheer” and cel- Description: Let there be light—a single ebrate the holiday season with a hilarious phrase, an unleashed beauty. By light’s illu- and heartwarming Christmas variety show mination we discern all the colors, contours, perfect for the entire family! Featuring your shapes, forms, and textures of our world. -

ENDER's GAME by Orson Scott Card Chapter 1 -- Third

ENDER'S GAME by Orson Scott Card Chapter 1 -- Third "I've watched through his eyes, I've listened through his ears, and tell you he's the one. Or at least as close as we're going to get." "That's what you said about the brother." "The brother tested out impossible. For other reasons. Nothing to do with his ability." "Same with the sister. And there are doubts about him. He's too malleable. Too willing to submerge himself in someone else's will." "Not if the other person is his enemy." "So what do we do? Surround him with enemies all the time?" "If we have to." "I thought you said you liked this kid." "If the buggers get him, they'll make me look like his favorite uncle." "All right. We're saving the world, after all. Take him." *** The monitor lady smiled very nicely and tousled his hair and said, "Andrew, I suppose by now you're just absolutely sick of having that horrid monitor. Well, I have good news for you. That monitor is going to come out today. We're going to just take it right out, and it won't hurt a bit." Ender nodded. It was a lie, of course, that it wouldn't hurt a bit. But since adults always said it when it was going to hurt, he could count on that statement as an accurate prediction of the future. Sometimes lies were more dependable than the truth. "So if you'll just come over here, Andrew, just sit right up here on the examining table. -

Nowyes632475.Pdf

Published by PEACHTREE PUBLISHING COMPANY INC. 1700 Chattahoochee Avenue Atlanta, Georgia 30318-2112 www.peachtree-online.com Text © 2021 by Bill Harley Cover and interior illustrations © by Pierre-Emmanuel Lyet All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. Edited by Vicky Holifield Cover design by Kate Gartner Interior design and composition by Adela Pons Printed in February 2021 by LSC Communications in Harrisonburg, VA in the United States of America. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 First Edition ISBN 978-1-68263-247-5 Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress. BILL H ARLEY To Debbie Block in all ways, always —B. H. Chapter ONE “The barbecue ones,” Conor says. “I know,” Mari says for the fourth time. “I don’t like the other ones. Especially not the vinegar ones. They’re bad.” Conor is standing sideways to the rows of snacks, facing the aisle that leads away from the meat section. His head is down—he’s not looking at her. He never looks at her. He’s not looking at anything except his fingers, which are opening and closing like they’re on the inside of a puppet and the puppet is talking. But the puppet is silent. It’s the motion of the hand that fascinates him, that has always fascinated him. -

Large Whale Restraint – Page 1 of 108 REPORT of LARGE WHALE

Large Whale Restraint – Page 1 of 108 REPORT OF LARGE WHALE RESTRAINT WORKSHOP Feb 7th & 8th 2006 AT CARRIAGE HOUSE WOODS HOLE OCEANOGRAPHIC INSTITUTION WOODS HOLE MA 02543 SPONSORED BY NATIONAL MARINE FISHERIES SERVICE Order # EM133F05SE5824 Requisition/ Reference # NFFM5100-5-00800 AUTHORS Andrea Bogomolni1, Regina Campbell-Malone1, Nadine Lysiak1 and Michael Moore2 1Rapporteurs, 2Chair Biology Department, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Woods Hole MA 02543 Large Whale Restraint – Page 2 of 108 Executive Summary The Problem: until large whale entanglements can be avoided, disentanglement is a necessary stop gap measure to enhance the survival of critically endangered large whales. Cases that are refractory to the standard protocols developed and used by the Provincetown Center for Coastal Studies (PCCS) are especially head and flipper wraps in right whales. There is a need both for immediately deployable solutions and development of better technology and techniques. Such advances must avoid proliferation of at sea personnel and include plans for next steps in each possible contingency. These are not currently supported within the Disentanglement Network or NOAA. History: two prior workshops resulted in a focus on the potential for sedation to enhance tractability, the delivery of hyper-concentrated Meperidine and Midazolam via a pole delivered, gas powered syringe to an entangled right whale, the acquisition of a working right whale tail model and its use to develop tail harness systems, and the conceptualization of a suction cup tag that could deliver drugs on demand and monitor the status of the individual. Experience from sedating marine mammals in captivity, and observation of sleeping right whales suggests that adequate tractability might be achieved in free swimming animals without significant loss of equilibrium. -

Enter the Cube by Nicholas and Daniel Dobkin January 2002 to December 2004

Enter the Cube by Nicholas and Daniel Dobkin January 2002 to December 2004 Table of Contents: Chapter 1: Playtime, Paytime ..............................................................................................................................................1 Chapter 2: Not in Kansas Any More....................................................................................................................................6 Chapter 3: A Quiz in Time Saves Six................................................................................................................................18 Chapter 4: Peach Pitstop....................................................................................................................................................22 Chapter 5: Copter, Copter, Overhead, I Choose Fourside for my Bed...........................................................................35 Chapter 6: EZ Phone Home ..............................................................................................................................................47 Chapter 7: Ghost Busted....................................................................................................................................................58 Chapter 8: Pipe Dreams......................................................................................................................................................75 Chapter 9: Victual Reality................................................................................................................................................102 -

Medeski Martin & Wood Last Chance to Dance Trance

Medeski Martin & Wood Last Chance To Dance Trance (Perhaps) Best Of (1991-1996) mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Jazz Album: Last Chance To Dance Trance (Perhaps) Best Of (1991-1996) Country: Canada Released: 1999 Style: Breakbeat, Jazz-Rock, Future Jazz, Drum n Bass MP3 version RAR size: 1859 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1238 mb WMA version RAR size: 1713 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 516 Other Formats: AA MP3 DMF MP2 WAV APE MP1 Tracklist Hide Credits Chubb Sub Edited By – Bob WardEdited By [With] – Bob WardMastered By – Dr. Toby 1 5:21 Mountain*Producer – David Baker, Jim Payne, MMW*Recorded By – David BakerWritten-By – Medeski Martin & Wood Bubblehouse Engineer [Assistant] – Carl Green, Mark KindermanEngineer [Recording] – David 2 4:28 BakerExecutive Producer – Hans WendlMastered By – Dr. Toby Mountain*Mixed By [With] – David Baker, Katsu NaitoProducer – db*, MMW*Written-By – MMW* Last Chance To Dance Trance (Perhaps) 3 Edited By – Bob WardMastered By – Dr. Toby Mountain*Producer – David Baker, Jim 7:38 Payne, MMW*Recorded By – David BakerWritten-By – Medeski Martin & Wood Hermeto's Daydream Edited By – Bob WardMastered By – Bob AppelMixed By – David Baker, John SiketRecorded 4 7:11 By [Baby Monster] – David BakerRecorded By [Water Music] – Roger TeltzmanWritten-By – Billy Martin, John Medeski Is There Anybody Here That Love My Jesus Arranged By – MMW*Edited By [With] – Bob WardEngineer [Assistant] – Carl Green, Mark 5 KindermanEngineer [Recording] – David BakerExecutive Producer – Hans WendlMastered 4:26 By – Dr. Toby Mountain*Mixed By [With] – David Baker, Katsu NaitoProducer – db*, MMW*Written-By – Traditional The Lover 6 Edited By – Bob WardMastered By – Dr.