2010 Outstanding First-Year Student Advocates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CASID Designated National Resource Center for International Studies By

CENTER FOR ADVANCED STUDY OF INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT FALL 2006 From the Director’s Desk CASID Designated National Resource Center The core faculty and staff for International Studies by U.S. Department of the Center for Advanced Study of International of Education for 2006–2010 Development (CASID) We are pleased to announce that MSU’s Center for Advanced Study of International at Michigan State Univer- Development, with the Women and International Development Program, has been sity are pleased to present designated by the U.S. Department of Education as a National Resource Center (NRC) the Fall 2006 issue of the for international development studies for the four-year cycle 2006–2010. This award will CASID Update, a com- provide support at MSU for programmatic activities related to international development prehensive newsletter on our programmatic and foreign language studies in the areas of teaching, research and outreach. The NRC activities. award is in addition to the four-year Foreign Language and Areas Studies (FLAS) Fellow- CASID is a multidisciplinary unit housed ship Program award that CASID and WID have received for 2006–2010. The NRC and in the College of Social Science and organized FLAS awards are in recognition of the strength, depth and breadth of MSU faculty in the in cooperation with the Office of the Dean of various fields of international development and institutional commitment to these areas. International Studies and Programs. CASID promotes and coordinates the study of issues related to international development from the perspective of the social sciences and liberal CASID Receives U.S. Department of State Funding for Nigeria arts. -

Student-Centered Teaching Practices We Choose to Teach College Students Because We Are Committed to the Proposition That Education Can Indeed Be Liberating

Student-Centered Teaching Practices We choose to teach college students because we are committed to the proposition that education can indeed be liberating. How we teach the students who enter our classrooms can make the difference between students who realize their potential and those who leave us discouraged about their possibilities. These resources, organized by topic, offer frameworks and strategies faculty can use to make their classrooms vibrant learning spaces for every student who walks through the door. Equity AAC&U (2018). A Vision for Equity: Results from AAC&U’s Project Committing to Equity and Inclusive Excellence: Campus-Based Strategies for Student Success. Available at: https://www.aacu.org/publications/vision-equity Gay, G. (2010). Culturally Responsive Teaching: Theory, Research and Practice (2nd Ed). New York: Teachers College Press. Hammond, Zaretta. Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain: Promoting Authentic Engagement and Rigor Among Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Students. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin. 2015. Delpit, Lisa. Other People’s Children : Cultural Conflict in the Classroom. New York : New Press ; York : Signature Book Services [distributor], 2006. Delpit, Lisa D. Multiplication Is for White People : Raising Expectations for Other People’s Children. New York : New Press ; London : Turnaround [distributor], 2013. McGuire, S. (2015). Teach Students How to Learn: Strategies You Can Incorporate into Any Course to Improve Student Metacognition, Study Skills and Motivation. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing. Pell Institute (2018). Indicators of Higher Education Equity in the United States – 2018 Historical Trend Report. Available at: http://pellinstitute.org/indicators/ Verschelden, C. (2017). Bandwidth Recovery: Helping Students Reclaim Cognitive Resources Lost to Poverty, Racism, and Social Marginalization. -

2021 Virtual Annual Meeting Program Meeting Program

NATIONAL HUMANITIES ALLIANCE 2021 Virtual Annual Meeting Program Meeting Program Monday, March 8th, 2021 All times are listed in Eastern Time. 12:00 - 12:15 p.m. Annual Meeting Welcome Join us to kick off the Annual Meeting with the launch of our new report, Strategies for Recruiting Students to the Humanities: A Comprehensive Resource. We will provide a brief overview of the report and the Annual Meeting’s offerings on advocating for the humanities on campus, in communities, and on Capitol Hill. Stephen Kidd, Executive Director, National Humanities Alliance; Beatrice Gurwitz, Deputy Director, National Humanities Alliance 12:30 - 1:30 p.m. Concurrent Sessions Defending Departments Under Review: Turning a Threat Into an Opportunity Learn from humanities faculty and administrators who have successfully navigated threats to humanities departments, rallied support for humanities education, and leveraged that support to launch initiatives to strengthen humanities programs. Jill Peterfeso, Chair, Religious Studies Department, Guilford College; Stephanie Patridge, Professor of Philosophy and Coordinator Liaison to the Arts and the Humanities, Otterbein University; Jessica Starling, Associate Professor of Religious Studies, Lewis & Clark College; Glenn Whitehouse, Associate Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, Florida Gulf Coast University Facilitator: Stephen Kidd, Executive Director, National Humanities Alliance Understanding the Impact of Humanities Programs on Community Life NHA’s Impact Survey Toolkit provides tools to document the impact of humanities work in communities, with an emphasis on the impacts that are most compelling to federal, state, and local policymakers. Learn more about how humanities programs strengthen communities as well as new additions to the toolkit that you can use in your own work. -

Document Attendance

PATHWAYS TO SOUTH ASIA: BUILDING GLOBAL STUDIES CAPACITIES AND OPPORTUNITIES RELATED TO SOUTH ASIA AND THE HINDI AND URDU LANGUAGES AT OAKTON COMMUNITY COLLEGE A multi-year intensive examination, expansion and revision of curriculum, faculty and staff professional development, and student study abroad opportunities to reflect the importance of South Asian content within global competency initiatives at Oakton Community College. INTRODUCTION Oakton Community College (“Oakton”), an open-access public community college serving 18 diverse communities in northern Cook County, Illinois, maintains a profound commitment to global studies, reflected in its Mission, Vision and Values statement, developed in 1998: “We challenge our students to be capable global citizens, guided by knowledge and ethical principles, who will shape the future.” This commitment also can be seen in the College’s strategic goals, “Change Matters,” which state: Figure 1: Change Matters: 2007-2012 Oakton Community College Strategic Goals Innovative learning for local and global citizenship. We will evaluate and change our academic programs and learning opportunities foster local and global citizenship and to meet clearly identified student and community needs. Oakton offers a comprehensive Global Studies (GS) Program, including an academic concentration in GS, on-campus GS special programming, various study abroad opportunities, two-year course of study in 11 modern languages, and a commitment to on-going international professional development for faculty, administrators and staff. The GS academic concentration allows for broad-based, interdisciplinary teaching and infusion of content across the spectrum of general education courses, thereby reaching students outside the GS concentration. GS students also may tailor their own program to focus on a particular area of the world or a particular issue, such as sustainable development. -

322-4176 (Office) Barbara.Clinton@ Vanderbilt.Edu PROFESSIONAL

Barbara Clinton (615) 322-4176 (office) barbara.clinton@ vanderbilt.edu PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE July 1988 - Present Director, Center for Health Services, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee. Responsible for four programs of service learning and community assistance. Supervise professional staff members, raise and manage annual budget of more than$1,000,000. Design, supervise and evaluate programs addressing maternal and child health, geriatric health, environment, cancer and nutrition. July 2002 – Present Adjunct Assistant Professor, Vanderbilt School of Medicine. April 1986 - Present Adjunct Assistant Professor, Vanderbilt University School of Nursing. July 1987 - June 1988 Acting Director, Center for Health Services. April 1981 - July 1987 Associate Director, Center for Health Services. October 1982 - August 1990 Director, Maternal Infant Health Outreach Worker (MIHOW) Project, a regional early intervention program in six states which identifies and trains local leaders as outreach workers. Supervised a professional staff of 32. March 1980 - April 1981 Senior Social Worker, Georgia Department of Medical Assistance, Athens, Georgia. Supervised the provision of community-based services to elderly clients in a ten-county rural area. Supervised casework staff. Provided training and consultation to service providers. March 1979 - January 1980 Intern, Northeast Georgia Community Mental Health Center, Athens, Georgia. Trained volunteers and professional clinical staff in working with ethnic and racial minorities. Authored a Family Life education curriculum for use in county school system. February 1977 - August 1978 Therapist, Buffalo Children's Hospital, Buffalo, New York. Therapy practice with children adjusting to growth and endocrine disorders. Provided individual, family and group treatment. Provided consultation to medical personnel. Lecturer, State University of New York at Buffalo, School of Medicine, Buffalo, New York. -

Georgia Tech, Georgia State University A0072 B0072

U.S. Department of Education Washington, D.C. 20202-5335 APPLICATION FOR GRANTS UNDER THE National Resource Centers and Foreign Language and Area Studies Fellowships CFDA # 84.015A PR/Award # P015A180072 Gramts.gov Tracking#: GRANT12659313 OMB No. , Expiration Date: Closing Date: Jun 25, 2018 PR/Award # P015A180072 **Table of Contents** Form Page 1. Application for Federal Assistance SF-424 e3 2. Standard Budget Sheet (ED 524) e6 3. Assurances Non-Construction Programs (SF 424B) e8 4. Disclosure Of Lobbying Activities (SF-LLL) e10 5. ED GEPA427 Form e11 Attachment - 1 (GT_GSU_GEPA_Section427_FINAL_19June20181021842892) e12 6. Grants.gov Lobbying Form e16 7. Dept of Education Supplemental Information for SF-424 e17 8. ED Abstract Narrative Form e18 Attachment - 1 (ABSTRACT_FINAL_22June20181021842932) e19 9. Project Narrative Form e20 Attachment - 1 (Table_of_contents___Narrative_1_1021842955) e21 10. Other Narrative Form e96 Attachment - 1 (Appendix_1_faculty_list_combined__6_20_18_FINAL_1021842934) e97 Attachment - 2 (Appendix_2_Course_list___6_20_18__FINAL1021842935) e335 Attachment - 3 (Appendix_3_PMFs_AGSC_FINAL_19June20181021842936) e435 Attachment - 4 (Appendix_4_letters_of_endorsement__FINAL_1021842937) e438 Attachment - 5 (Appendix_5_GT_AbsolutePriority_1_2_Statement_FINAL1021842968) e456 Attachment - 6 (Appendix_6_GSU_AbsolutePriority_1_2_Statement_FINAL1021842939) e459 Attachment - 7 (Appendix_7_FY2018_ProfileForm_GeorgiaTech_FINAL_22June20181021842940) e462 11. Budget Narrative Form e463 Attachment - 1 (Combined_Budget1021842933) -

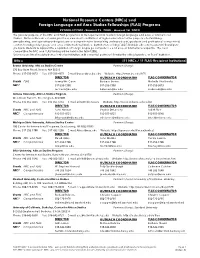

Nrcs) and Foreign Language and Area Studies Fellowships (FLAS

National Resource Centers (NRCs) and Foreign Language and Area Studies Fellowships (FLAS) Programs FY2000-FY2002 (August 15, 2000 - August 14, 2003) The general purpose of the NRC and FLAS programs is to train specialists in modern foreign language and area or international studies. National Resource Center grants are awarded to institutions of higher education for the purpose of establishing, strengthening, and operating undergraduate or comprehensive (containing undergraduate, graduate and professional components) centers focusing on language and area or international studies. Institutions receiving FLAS Fellowship allocations award fellowships to graduate students to support the acquisition of foreign language competence and area or international expertise. The next competition for NRC and FLAS funding will be held in the fall of 2002. Grantees are listed in alphabetical order by institution, with consortial partners following the official grantee, or "lead" institution. Africa [11 NRCs / 11 FLAS-Recipient Institutions] Boston University, African Studies Center Partners (if any): 270 Bay State Road, Boston, MA 02215- Phone 617-353-3673 Fax: 617-353-4975 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.bu.edu/AFR DIRECTOR OUTREACH COORDINATOR FLAS COORDINATOR Grants FLAS James Mc Cann Barbara Brown Michelle Uter Brooks NRC? 617-353-7308 6173537308 617-353-7303 617-353-3673 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Indiana University, African Studies Program Partners (if any): Woodburn Hall 221, Bloomington, IN 47405 Phone 812-855-6825 -

CLAS Designated a National Resource Center • Carlos Jáuregui Mines the Treasures of the Eduardo Lozano Lati

UNI VE RSI TY OF P I TTSBURGH UNI VE RSI TY CE NTE R FOR I NTE RNATI ONAL STUDI E S CENTER FOR LATIN AMERICAN STUDIES SUMME R 2003 54 INSIDE: • CLAS Designated a National Resource Center • Carlos Jáuregui Mines the Treasures of the Eduardo Lozano Latin American Library Collection • Brazil Business Briefing • Graduate Student Conference on Latin American Social and Public Policy 02 SUMMER 2003 Designated a National Resource Center on Latin American Studies The Center for Latin American Studies (CLAS) at the University of Comprehensive NRCs (Consortia) Pittsburgh has again been recognized as one of the top programs • UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA, Center for Latin American on the region in the United States. Every three years, major area Studies, with ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY, Center for studies programs at universities throughout the U.S. enter a Latin American Studies formidable competition conducted by the U.S. Department of • UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA, Center for Latin American Education for the distinction of being named a National Resource Studies, with FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY, C e n t e r ( N R C ) . S i x t e e n N R C s o n t h e L a t i n A m e r i c a n a n d Latin American and Caribbean Center Caribbean region were selected for 2003 through 2006, and • UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN, CLAS—in consortium with the Latin American Studies Program Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies, with at Cornell University—continues to be counted among these UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO, Center for Latin American distinguished programs. -

Thelatinamericanist

The LATINAMERICANIST University of Florida Center for Latin American Studies | Volume 49, Number 2 | Fall 2018 Inside this Issue 2 Director’s Corner 7 Center News 11 Student Spotlight 15 LAS Alumni Awards 1 DIRECTOR’S Corner The LATINAMERICANIST Volume 49, Number 2 | Fall 2018 e began students from underrepresented Center for Latin American Studies the groups with expanded area and 319 Grinter Hall W PO Box 115530 fall semester language studies opportunities will Gainesville, FL 32611-5530 with some contribute to preparing more and (352) 392-0375 exciting news. better-qualified LAS specialists in www.latam.ufl.edu The Center areas of national need. Center-Based Faculty for Latin American In addition, the Center will be able Philip Williams Susan Paulson Studies to enhance its outreach to K-12 Director Assoc. Director, was again pre-service and in-service teachers, Academic Programs Efraín Barradas (LAS) designated as a Title VI National strengthen collaborations with (LAS/SPS) Resource Center (NRC) by the Minority-Serving Institutions and Rosana Resende Department of Education and community colleges, and expand Emilio Bruna Assoc. Director, FBLI Director, FBLI (LAS) received Foreign Language and outreach to business, media, and (LAS/WEC) Area Studies (FLAS) fellowship the general public. The FLAS Mary Risner funding for 2018-22. The Center will fellowship grant will support Joel Correia Assoc. Director, (LAS) Outreach & LABE receive approximately $1.9 million in graduate and undergraduate (LAS) funding during the four-year cycle. students to pursue language Jonathan Dain training in Portuguese and Haitian (LAS/SFRC) Tanya Saunders (LAS/CWSGR) With Title VI NRC support, Latin Creole during the academic year Glenn Galloway American Studies (LAS) faculty while supporting the study of these Director, MDP Marianne Schmink at UF will benefit from increased and other less commonly taught (LAS) (LAS) research and training opportunities languages during the summer. -

National Resource Center for the First-Year Experience and Students in Transition

VITAE DATE: 12.17.18 NAME: Jean M. Henscheid ORGANIZATION: National Resource Center for The First-Year Experience and Students in Transition TITLE: Fellow CONTACT: [email protected] c/o 12200 West Seven Lakes Lane Star, Idaho 83669 EDUCATION: 1996 Ph.D. in Education, Washington State University (Dorothy B. Cook outstanding graduate student). Emphasis: Sociology of college student learning. 1992 Master of Public Administration (Phi Kappa Phi), Idaho State University. 1983 Bachelor of Arts, Idaho State University. History major, English minor. CERTIFICATE: Human Subjects Research online course, sponsored by the Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative, completed January 7, 2015. DOCTORAL DISSERTATION: Henscheid, J. M. (1996). Residential learning communities and the freshman year. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Washington State University, Pullman. EDUCATION EXPERIENCE: Higher education teaching, research, and administrative appointments 2001-Present Fellow, National Resource Center for The First-Year Experience and Students in Transition University of South Carolina, Columbia. 2017-2018 Principal Policy Analyst, Idaho State Board of Education, Boise, ID J. M. HENSCHEID, Page 2 of 16 2017 Interim Director, James A. and Louise McClure Center for Public Policy Research, University of Idaho. 2016-2017 Research Scientist, James A. and Louise McClure Center for Public Policy Research, University of Idaho. 2013-2016 Clinical Assistant Professor and Program Co-Coordinator, Adult, Organizational Learning and Leadership, Department of Leadership and Counseling, University of Idaho. 2013-2014 Program Co-Coordinator, Professional Practices Doctorate, College of Education, University of Idaho. 2011-2013 Fixed-Term Associate Professor and Senior Scholar, Department of Educational Leadership and Policy, Portland State University. 2008-2014 Executive Editor, About Campus, ACPA/College Student Educators International. -

News from Sponsoring Organizations

News From Our Sponsors NEWS FROM SPONSORING ORGANIZATIONS Sponsors University of Hawai`i National Foreign Language Resource Center (NFLRC) Michigan State University Center for Language Education and Research (CLEAR) Co-Sponsor Center for Applied Linguistics (CAL) University of Hawai'i National Foreign Language Resource Center (NFLRC) The University of Hawai‘i National Foreign Language Resource Center engages in research and materials development projects and conducts workshops and conferences for language professionals among its many activities. 2008 SECOND LANGUAGE RESEARCH FORUM With the theme, Exploring SLA: Perspectives, Positions, and Practices, the Second Language Research Forum (SLRF) returns to the University of Hawai‘i at Manoa for the third time on October 17-19, 2008 (with the NFLRC serving as co-sponsor). Highlights include plenary talks by Harald Clahsen (University of Essex), Alan Firth (Newcastle University), Carmen Muñoz (Universitat de Barcelona), & Richard Schmidt (University of Hawai‘i at Manoa); 4 colloquia; and over 150 paper and poster sessions. Visit our website for more information. 1ST INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON LANGUAGE DOCUMENTATION & CONSERVATION: SUPPORTING SMALL LANGUAGES The 1st International Conference on Language Documentation and Conservation (ICLDC) will be held at the University of Hawai‘i at Manoa from March 12-14, 2009. There will also be an optional opportunity to visit Hilo, on the Big Island of Hawai'i, in an extension of the conference that will focus on the Hawaiian language revitalization program, March 16-17. Conference sponsors include the UH National Foreign Language Resource Center, National Resource Center East Asia, and Center for Pacific Island Studies. It has been a decade since Himmelmann's article on language documentation appeared and focused the field into thinking in terms of creating a lasting record of a language that could be used by speakers as well as by academics. -

The Macmillan Center for International and Area Studies at Editor: David J

September 10, 2006 ale university 2007 – Number 15 bulletin of y Series 102 The MacMillan Center for International and Area Studies 2006 bulletin of yale university September 10, 2006 MacMillan Center Periodicals postage paid New Haven, Connecticut 06520-8227 ct bulletin of yale university bulletin of yale New Haven Bulletin of Yale University The University is committed to basing judgments concerning the admission, education, and employment of individuals upon their qualifications and abilities and affirmatively seeks to attract Postmaster: Send address changes to Bulletin of Yale University, to its faculty, staff, and student body qualified persons of diverse backgrounds. In accordance with PO Box 208227, New Haven ct 06520-8227 this policy and as delineated by federal and Connecticut law, Yale does not discriminate in admis- sions, educational programs, or employment against any individual on account of that individual’s PO Box 208230, New Haven ct 06520-8230 Periodicals postage paid at New Haven, Connecticut sex, race, color, religion, age, disability, status as a special disabled veteran, veteran of the Vietnam era, or other covered veteran, or national or ethnic origin; nor does Yale discriminate on the basis Issued seventeen times a year: one time a year in May, November, and December; two times of sexual orientation. a year in June; three times a year in July and September; six times a year in August University policy is committed to affirmative action under law in employment of women, minority group members, individuals with disabilities, special disabled veterans, veterans of the Managing Editor: Linda Koch Lorimer Vietnam era, and other covered veterans.