Anthropology of the Weird L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historical Perspective

Journal of Scientific Exploration, Vol. 34, No. 4, pp. 717–754, 2020 0892-3310/20 HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE Early Psychical Research Reference Works: Remarks on Nandor Fodor’s Encyclopaedia of Psychic Science Carlos S. Alvarado [email protected] Submitted March 11, 2020; Accepted July 5, 2020; Published December 15, 2020 DOI: 10.31275/20201785 Creative Commons License CC-BY-NC Abstract—Some early reference works about psychic phenomena have included bibliographies, dictionaries, encyclopedias, and general over- view books. A particularly useful one, and the focus of the present article, is Nandor Fodor’s Encyclopaedia of Psychic Science (Fodor, n.d., circa 1933 or 1934). The encyclopedia has more than 900 alphabetically arranged entries. These cover such phenomena as apparitions, auras, automatic writing, clairvoyance, hauntings, materialization, poltergeists, premoni- tions, psychometry, and telepathy, but also mediums and psychics, re- searchers and writers, magazines and journals, organizations, theoretical ideas, and other topics. In addition to the content of this work, and some information about its author, it is argued that the Encyclopaedia is a good reference work for the study of developments from before 1933, even though it has some omissions and bibliographical problems. Keywords: Encyclopaedia of Psychic Science; Nandor Fodor; psychical re- search reference works; history of psychical research INTRODUCTION The work discussed in this article, Nandor Fodor’s Encyclopaedia of Psychic Science (Fodor, n.d., circa 1933 or 1934), is a unique compilation of information about psychical research and related topics up to around 1933. Widely used by writers interested in overviews of the literature, Fodor’s work is part of a reference literature developed over the years to facilitate the acquisition of knowledge about the early publications of the field by students of psychic phenomena. -

Modern Spiritualism: Its Quest to Become a Science Creative Works

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Modern Spiritualism: Its Quest to Become A Science Creative Works 2021 Modern Spiritualism: Its Quest to Become A Science John Haller Jr Follow this and additional works at: https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/histcw_ms Copyright © 2020, John S. Haller, Jr. All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN (print): 9798651505449 Interior design by booknook.biz This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Creative Works at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Modern Spiritualism: Its Quest to Become A Science by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Modern Spiritualism: Its Quest to Become A Science By John S. Haller, Jr. Copyright © 2020, John S. Haller, Jr. All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN (print): 9798651505449 Interior design by booknook.biz Spiritualism, then, is a science, by authority of self-evident truth, observed fact, and inevitable deduction, having within itself all the elements upon which any science can found a claim. (R. T. Hallock, The Road to Spiritualism, 1858) TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 Chapters 1. Awakening 11 2. Rappings 41 3. Poughkeepsie Seer 69 4. Architect of the Spirit World 95 5. Esoteric Wisdom 121 6. American Portraits 153 7. -

Hours with the Ghosts, Or, Nineteenth Century Witchcraft : Illustrated

&* \3 1<* .• J& ^ *ti ._$& - C> * *> v .'* v %. & «\ : - ^ • ^ r o. **?CT* A • Av 0* »°JL** "*b * . 4* V ,>^>- V%T' , >*."• xWV/,.aA :- ^d* • ,*- **'*0n« .'j w e$^ ,v^. .c, tfv -.- <r% i^^ V S\ r «^ ••«•" ^ ** ' V ^ ** \& ..**' t?' .'J&l-*** V > G°* .^>>o ^o< • * ^ **•:? 0* • L^L'* '^TVi* A o, **T.T« A <> * *£_ %\ % 4» ^-\y V^-'V \y*l*z>\# Sir.- ^% ^ r-\ ..«, A* 1 • o > Ao * ^ i> v;^>°u>;; ^\^^'^, f-' y A C *• #°+ / aO v*^?r- # -^ ,» *. "%/' % ^ i^ /js |: V** :*»t ;*; — Hours With the Ghosts OR NINETEENTH CENTURY WITCHCRAFT Ltf ILLUSTRATED INVESTIGATIONS Phenomena of Spiritualism and Theosophy Henry Ridgely' Evans The first duty we owe to the world is Truth—all the Truth—nothing but the Truth. "Ancient Wisdom." CHICAGO LAIRD & LEE, PUBLISHERS £681 LZ 100 rA *<V Entered according to act of Congress, in the year eighteen hundred and ninety-seven. By WILLIAM H. LEE, In the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington. TO MY WIFE — ' " It is no proof of wisdom to refuse to examine certain phe- nomena because we think it certain that they are impossible, as if our knowledge of the universe were already completed. ' —Prof. Lodge. ' ' The most ardent Spiritist should welcome a searching in- quiry into the potential faculties of spirits still in the flesh. Until we know more of these, those other phenomena to which he appeals must remain unintelligible because isolated, and are likely to be obstinately disbelieved because they are impos- sible to understand." F. W. H. Myers: "Proceedings of the Societyfor Psychical Research^ Part XVIII, April, 1891. TABLE OF CONTENTS. -

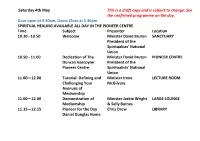

Saturday 4Th May Open Week Draft Programme

Saturday 4th May This is a draft copy and is subject to change. See the confirmed programme on the day. Door open at 9.30am, Doors Close at 5.30pm SPIRITUAL HEALING AVAILABLE ALL DAY IN THE PIONEER CENTRE Time Subject Presenter Location 10.30 –10.50 Welcome Minister David Bruton SANCTUARY President of the Spiritualists' National Union 10.50 - 11.00 Dedication of The Minister David Bruton PIONEER CENTRE Duncan Gascoyne President of the Pioneer Centre Spiritualists' National Union 11.00—12.00 Tutorial: Defining and Minister Irene LECTURE ROOM Challenging Your McGilvary Avenues of Mediumship 11.00—12.00 Demonstration of Minister Jackie Wright LARGE LOUNGE Mediumship & Sally Barnes 11.15—12.15 Pioneer for the Day Chris Drew LIBRARY Daniel Dunglas Home 12.15 - 1.15 Demonstration of Minister Colin Bates LECTURE ROOM Mediumship and Lynn Parker 11.30 - 12.30 Trance Demonstration Minister Judith Seaman SANCTUARY 12.30—1.30 An appointment with Libby Clarke OSNU LARGE LOUNGE Dr. James Trance Healing 12.30—1.30 The Saturday debate - Minister David R LIBRARY Search for the True Bruton, Minister Jackie message of Spiritualism Wright & John Blackwood OSNU 12.45—1.45 Demonstration of GORDON HIGGINSON SANCTUARY Mediumship Scholarship Students 1.30 - 2.30 Trance Healing Minister Steven Upton LECTURE ROOM Demonstration 2.45 - 3.45 Lecture: Shamanic soul Maureen Murnan LECTURE ROOM 2.00 - 300 Demonstration of Penny Hayward & Julie LIBRARY Mediumship Grist 2.15 - 315 "Branching out - Alv Hirst GARDEN Subject to philosophy to take us weather further.' 2.00—3.00 -

Georgiana Houghton Spirit Drawings Georgiana Houghton Spirit Drawings

GEORGIANA HOUGHTON SPIRIT DRAWINGS GEORGIANA HOUGHTON SPIRIT DRAWINGS Simon Grant, Lars Bang Larsen and Marco Pasi edited by Ernst Vegelin van Claerbergen and Barnaby Wright First published to accompany GEORGIANA HOUGHTON: SPIRIT DRAWINGS The Courtauld Gallery, London, 16 June – 11 September 2016 Organised in collaboration with Monash University Museum of Art CONTENTS The Courtauld Gallery is supported by the Higher Education Funding Council for England (hefce) 6 Director’s Foreword 8 “Works of art without parallel in the world” Georgiana Houghton’s Spirit Drawings Copyright © 2016 simon grant and marco pasi Texts copyright © the authors All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any storage or retrieval system, without the 24 Spectres of Art prior permission in writing from the copyright holder and publisher. lars bang larsen and marco pasi isbn 9781 911300 02 1 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library 34 CATALOGUE Produced by Paul Holberton publishing 89 Borough High Street, London se1 1nl 36 Catalogue Introduction www.paul-holberton.net Designed by Laura Parker ernst vegelin van claerbergen and barnaby wright Printing by Gomer Press, Llandysul front cover: Detail of cat. 7, The Eye of God; frontispiece: Detail of cat. 19, The Eye of the Lord; page 7: Detail of cat. 4, 82 List of Works Flower of William Harman Butler; page 8: Detail of cat. 12, The Risen Lord; page 17: Detail of verso of cat. 15, The Eye of the Lord; page 24: Detail of cat. -

Florence Cook

Florence Cook Florence Eliza Cook (ca 1856 – 22 April 1904) was a medium who claimed to materialise a spirit, "Katie King". The question of whether the spirit was real or a fraud was a notable public controversy of the mid-1870s. Her abilities were endorsed by Sir William Crookes but many observers were skeptical of Crookes's investigations, both at the time and subsequently. Contents Biography Notes References External links Katie King, Florence Cook and Sir Biography William Crookes Cook was a teenage girl who started to claim mediumistic abilities in 1870 and in 1871–2 she developed her abilities under the established mediums Frank Herne and Charles Williams. Herne was associated with the spirit "John King", and Florence became associated with "Katie King", stated to be John King's daughter. Herne was exposed as a fraud in 1875.[1] Katie King developed from appearing as a disembodied face to a fully physical materialisation.[2] The spirit was said to have appeared first between 1871 and 1874 in séances conducted by Florence Cook in London, and later in 1874–1875 in New York in séances held by the mediums Jennie Holmes and her husband Nelson Holmes. Katie King was believed by Spiritualists to be the daughter of John King, a spirit control of the 1850s through the 1870s that appeared in many séances involving materialised spirits. A spirit control is a powerful and communicative spirit that organises the appearance of other spirits at a séance. John King claimed to be the spirit of Henry Morgan, the buccaneer (Doyle 1926: volume 1, 241, 277). -

The Return of the Victorian Occult in Contemporary Fiction

The Return of the Victorian Occult 1 in Contemporary Fiction Rosario Arias The 1990s have witnessed the flourishing of a language suffused with ghosts, revenants and spectral forms. In fact, Roger Luck- hurst2 suggests that the relevance of spectrality in a wide variety of literary contexts involves, what he calls, a “spectral turn”.3 In this paper I undertake the examination of this idea of spectrality or haunting as the persistent presence of the Victorian occult, and, more specifically, spiritualism, in contemporary narratives like A. S. Byatt’s “The Conjugial Angel” (1992)4, Sarah Waters’s Affinity (1999)5 and Julian Barnes’s Arthur and George (2005),6 among others. While the neo-Victorian novel has recently become the subject of many critical studies, a literary type of the neo-Victorian novel that revisits the Victorian past through its involvement with the occult has received relatively little exploration. Accordingly, the return of the Victorian occult in twentieth- and twenty-first century fiction will be analysed against the backdrop of notions of spectrality, haunting and ghostly returns, which are now being privileged in critical and literary discourses, as well as in the light of recent scholarship about the Victorian occult. Lastly, I would like to demonstrate that the spectral visitation of the Victorian occult in 1 The research carried out for the writing of this article has been financed by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Technology: BFF2003-05143 / FEDER. This article is an expanded version of a paper delivered at the Conference “The Twentieth Century and the Victorians”, held at Trinity and All Saints College (University of Leeds) in July 2005. -

Edinburgh Research Explorer

Edinburgh Research Explorer Spiritualism and a mid-Victorian crisis of evidence Citation for published version: Lamont, P 2004, 'Spiritualism and a mid-Victorian crisis of evidence' Historical Journal, vol 47, no. 4, pp. 897-920., 10.1017/S0018246X04004030 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1017/S0018246X04004030 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher final version (usually the publisher pdf) Published In: Historical Journal Publisher Rights Statement: © Lamont, P. (2004). Spiritualism and a mid-Victorian crisis of evidence. Historical Journal, 47(4), 897-920doi: 10.1017/S0018246X04004030 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 11. Jun. 2015 The Historical Journal http://journals.cambridge.org/HIS Additional services for The Historical Journal: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here SPIRITUALISM AND A MID-VICTORIAN CRISIS OF EVIDENCE PETER LAMONT The Historical Journal / Volume 47 / Issue 04 / December 2004, pp 897 - 920 DOI: 10.1017/S0018246X04004030, Published online: 29 November 2004 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0018246X04004030 How to cite this article: PETER LAMONT (2004). -

Hamiltont.Pdf

1 A critical examination of the methodology and evidence of the first and second generation elite leaders of the Society for Psychical Research with particular reference to the life, work and ideas of Frederic WH Myers and his colleagues and to the assessment of the automatic writings allegedly produced post-mortem by him and others (the cross- correspondences). Submitted by Trevor John Hamilton to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by Publication (PT) in June 2019.This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and no material has been previously submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature…………………………… 2 Abstract This thesis outlines the canons of evidence developed by the elite Cambridge- based and educated leaders of the Society for Psychical Research to assess anomalous phenomena, and second, describes the gradual shift away from that approach, by their successors and the reasons for such a partial weakening of those standards, and the consequences for the general health of the SPR .It argues that, for a variety of reasons, this methodology has not always been fully appreciated or described accurately. Partly this is to do with the complex personality of Myers who provoked a range of contradictory responses from both contemporaries and later scholars who studied his life and work; partly to do with the highly selective criticisms of his and his colleagues’ work by TH Hall (which criticisms have entered general discourse without proper examination and challenge); and partly to a failure fully to appreciate how centrally derived their concepts and approaches were from the general concerns of late-Victorian science and social science. -

Spreading the Spirit Word: Print Media, Storytelling, and Popular Culture

communication +1 Volume 4 Issue 1 Occult Communications: On Article 12 Instrumentation, Esotericism, and Epistemology September 2015 Spreading the Spirit Word: Print Media, Storytelling, and Popular Culture in Nineteenth-Century Spiritualism Simone Natale Loughborough University, [email protected] Abstract Spiritualists in the nineteenth century gave much emphasis to the collection of evidences of scientific meaning. During séances, they used instruments similar to those employed in scientific practice to substantiate their claims. However, these were not the only source of legitimization offered in support of the spiritualist claims. In fact, writers who aimed to provide beliefs in spiritualism with a reliable support relied very often on the testimonies of eyewitness that were reported in a narrative fashion. This article interrogates the role of such anecdotal testimonies in nineteenth-century spiritualism. It argues that they played a twofold role: on one side, they offered a form of evidentiary proof that was complementary to the collection of mechanical-based evidences; on the other side, they circulated in spiritualist publications, creating opportunities to reach a wide public of readers that was made available by the emergence of a mass market for print media. Able to convince, but also to entertain the reader, anecdotal testimonies were perfectly suited for publications in spiritualist books and periodicals. The proliferation of anecdotal testimonies in spiritualist texts, in this regard, hints at the relevance of storytelling in the diffusion of beliefs about religious matters as well as scientific issues within the public sphere. By reporting and disseminating narrative testimonies, print media acted as a channel through which spiritualism’s religious and scientific endeavors entered the field of a burgeoning popular culture. -

Bibliography of Occult and Fantastic Beliefs Vol.2: E-K

Bruno Antonio Buike, editor / undercover-collective „Paul Smith“, alias University of Melbourne, Australia Bibliography of Occult and Fantastic Beliefs vol.2: E-K © Neuss / Germany: Bruno Buike 2017 Buike Music and Science [email protected] BBWV E28 Bruno Antonio Buike, editor / undercover-collective „Paul Smith, alias University of Melbourne, Australia Bibliography of Occult and Fantastic Beliefs - vol.2: E-K Neuss: Bruno Buike 2017 CONTENT Vol. 1 A-D 273 p. Vol. 2 E-K 271 p. Vol. 3 L-R 263 p. Vol. 4 S-Z 239 p. Appr. 21.000 title entries - total 1046 p. ---xxx--- 1. Dies ist ein wissenschaftliches Projekt ohne kommerzielle Interessen. 2. Wer finanzielle Forderungen gegen dieses Projekt erhebt, dessen Beitrag und Name werden in der nächsten Auflage gelöscht. 3. Das Projekt wurde gefördert von der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Sozialamt Neuss. 4. Rechtschreibfehler zu unterlassen, konnte ich meinem Computer trotz jahrelanger Versuche nicht beibringen. Im Gegenteil: Das Biest fügt immer wieder neue Fehler ein, wo vorher keine waren! 1. This is a scientific project without commercial interests, that is not in bookstores, but free in Internet. 2. Financial and legal claims against this project, will result in the contribution and the name of contributor in the next edition canceled. 3. This project has been sponsored by the Federal Republic of Germany, Department for Social Benefits, city of Neuss. 4. Correct spelling and orthography is subject of a constant fight between me and my computer – AND THE SOFTWARE in use – and normally the other side is the winning party! Editor`s note – Vorwort des Herausgebers preface 1 ENGLISH SHORT PREFACE „Paul Smith“ is a FAKE-IDENTY behind which very probably is a COLLCETIVE of writers and researchers, using a more RATIONAL and SOBER approach towards the complex of Rennes-le-Chateau and to related complex of „Priory of Sion“ (Prieure de Sion of Pierre Plantard, Geradrd de Sede, Phlippe de Cherisey, Jean-Luc Chaumeil and others). -

Spiritualist Ritual and the Performance of Belief: Spirit Communication in Twenty-First Century America

ABSTRACT Title of Document: SPIRITUALIST RITUAL AND THE PERFORMANCE OF BELIEF: SPIRIT COMMUNICATION IN TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY AMERICA Robert C. Thompson, Doctor of Philosophy, 2013 Directed By: Assistant Professor, Dr. Laurie Frederik Meer, School of Theatre, Dance, and Performance Studies Spiritualism is an alternative religion focused on establishing contact between living participants and the spirits of the dead, dating to the mid nineteenth century. Drawing on eighteen months of ethnographic research at the Center for Spiritual Enlightenment in Falls Church, Virginia, I analyze the three primary rituals of Spiritualist practice—spirit messages, spirit healing, and unfoldment—and argue that performance is central to Spiritualists' ability to connect with the spirit world in a way that can be intersubjectively confirmed by more than one participant. Spirit messages are performed by mediums to a congregation or audience in order to prove to individual spectators that their deceased loved ones have continued to exist as disembodied spirits after their deaths. Spirit healing is performed by healers who channel the energy of the spirits into participants in order to improve the participant's mental, physical, and spiritual condition. And unfoldment is the process whereby Spiritualists study and practice to be able to make their own direct personal contact with the spirit world. Spiritualism purports to be a science, religion, and philosophy. I consider the intersection between criticism of empirical evidence and entertainment in order to establish how Spiritualists attract newcomers and the intersection between religious belief and ritual participation in order to establish why newcomers choose to become converts. I consider Spiritualism's early history in order to discover the nature of the delicate balance that criticism and belief have established in Spiritualist practice.