Spiritualism, Science and the Su?€Rnatural in Rnid-Vi Cto Ri an Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historical Perspective

Journal of Scientific Exploration, Vol. 34, No. 4, pp. 717–754, 2020 0892-3310/20 HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE Early Psychical Research Reference Works: Remarks on Nandor Fodor’s Encyclopaedia of Psychic Science Carlos S. Alvarado [email protected] Submitted March 11, 2020; Accepted July 5, 2020; Published December 15, 2020 DOI: 10.31275/20201785 Creative Commons License CC-BY-NC Abstract—Some early reference works about psychic phenomena have included bibliographies, dictionaries, encyclopedias, and general over- view books. A particularly useful one, and the focus of the present article, is Nandor Fodor’s Encyclopaedia of Psychic Science (Fodor, n.d., circa 1933 or 1934). The encyclopedia has more than 900 alphabetically arranged entries. These cover such phenomena as apparitions, auras, automatic writing, clairvoyance, hauntings, materialization, poltergeists, premoni- tions, psychometry, and telepathy, but also mediums and psychics, re- searchers and writers, magazines and journals, organizations, theoretical ideas, and other topics. In addition to the content of this work, and some information about its author, it is argued that the Encyclopaedia is a good reference work for the study of developments from before 1933, even though it has some omissions and bibliographical problems. Keywords: Encyclopaedia of Psychic Science; Nandor Fodor; psychical re- search reference works; history of psychical research INTRODUCTION The work discussed in this article, Nandor Fodor’s Encyclopaedia of Psychic Science (Fodor, n.d., circa 1933 or 1934), is a unique compilation of information about psychical research and related topics up to around 1933. Widely used by writers interested in overviews of the literature, Fodor’s work is part of a reference literature developed over the years to facilitate the acquisition of knowledge about the early publications of the field by students of psychic phenomena. -

Palmistry: Science Or Hand-Jive?

the Skeptical Inquirer PALMISTRY: SCIENCE OR HAND-JIVE? SRI GELLER TEST / LOCHNESS TREE TRUNK / A PILOT'S UFO WHY SKEPTICS ARE SKEPTICAL VOL. VII No. 2 WINTER 191 Published by the Committee lor the Scientific Investigation of :of the Paranormal Skeptical Inquirer THE SKEPTICAL. INQUIRER is the official journal of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal. Editor Kendrick Frazier. Editorial Board George Abell. Martin Gardner. Ray Hyman. Philip J. Klass, Paul Kurtz, James Randi. Consulting Editors James E. Alcock, Isaac Asimov, William Sims Bainbridge. John Boardman, Milbourne Christopher. John R. Cole. Richard de Mille, C.E.M. Hansel, E.C. Krupp. James Oberg. Robert Sheaffer. Assistant Editor Doris Hawley Doyle. Production Editor Belsy Offermann. Business Manager Lynette Nisbet. Office Manager Mary Rose Hays Staff Idelle Abrams. Judy Hays. Alfreda Pidgeon Cartoonist Rob Pudim The Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal Paul Kurtz, Chairman; philosopher. State University of New York at Buffalo. Lee Nisbet, Executive Director; philosopher, Medaille College. Fellows of the Committee: George Abed, astronomer, UCLA; James E. Alcock, psychologist, York Univ., Toronto; Isaac Asimov, chemist, author; Irving Biederman, psychologist. SUNY at Buffalo; Brand Blanshard, philosopher, Yale; Bart J. Bok, astronomer. Steward Observatory, Univ. of Arizona; Bette Chambers, A.H.A.; Milbourne Christopher, magician, author; L. Sprague de Camp, author, engineer; Bernard Dixon, European Editor, Omni; Paul Edwards, philosopher. Editor, Encyclopedia of Philosophy; Charles Fair, author, Antony Flew, philosopher, Reading Univ., O.K.: Kendrick Frazier, science writer. Editor. THE SKEPTICAL. INQUIRER; Yves Galifret, Exec. Secretary, I'Union Rationaliste; Martin Gardner, author. -

Magicians on the Paranormal: an Essay with a Review of Three Books

Magicians on the Paranormal: An Essay with a Review of Three Books GEORGE P. HANSEN’ ABSTRACT: Conjurors have written books on the paranormal since the 1500s. A number of these books are listed and briefly discussed herein, including those of both skeptics and proponents. Lists of magicians on both sides of the psi controversy are provided. Although many people perceive conjurors to be skeptics and debunkers, some of the most prominent magicians in history have endorsed the reality of psychic phenomena. The reader is warned that conjurors’ public statements asserting the reality of psi are sometimes difficult to eval- uate. Some mentalists publicly claim psychic abilities but privately admit that they do not believe in them; others privately acknowledge their own psychic experiences. Thme current books are fully reviewed: EntraSensory Deception by Henry Gordon (1987), Forbidden Knowledge by Bob Couttie (1988), and Secrets of the Supernatural by Joe Nickel1 (with Fischer, 1988). The books by Gordon and Couttie contain serious errors and are of little value, but the work by Nickel1 is a worthwhile contribution, though only partially concerned with psi. Magicians have been involved with paranormal controversies for cen- turies, and their participation has been far more complex and multifaceted than the usual stereotype of magicians as skeptical debunkers. In this paper, I review three fairly recent skeptical books by magicians, but before these are discussed, some remarks are in order concerning conjurors’ in- volvement with psi and psi research because there has been little useful discussion of the topic in the parapsychology literature.’ It is important to understand this background because several magicians have had an impact on scientists’ and the general public’s perception of psychical research, and some have played a major role in the modem-day skeptical movement (Hansen, 1992). -

The 'World of the Infinitely Little'

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE The 'world of the infinitely little': connecting physical and psychical realities circa 1900 AUTHORS Noakes, Richard JOURNAL Studies In History and Philosophy of Science Part A DEPOSITED IN ORE 01 December 2008 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10036/41635 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication THE ‘WORLD OF THE INFINITELY LITTLE’: CONNECTING PHYSICAL AND PSYCHICAL REALITIES IN BRITAIN C. 1900 RICHARD NOAKES I: INTRODUCTION In 1918 the ageing American historian Henry Adams recalled that from the 1890s he had received a smattering of a scientific education from Samuel Pierpont Langley, the eminent astrophysicist and director of the Smithsonian Institution. Langley managed to instil in Adams his ‘scientific passion for doubt’ which undoubtedly included Langley’s sceptical view that all laws of nature were mere hypotheses and reflections of the limited and changing human perspective on the cosmos.1 Langley also pressed into the hands of his charge several works challenging the supposedly robust laws of ‘modern’ physics.2 These included the notorious critiques of mechanics, J. B. Stallo’s Concepts and Theories of Modern Physics (1881) [AND] Karl Pearson’s Grammar of Science (1892), and several recent numbers of the Smithsonian Institution’s -

Modern Spiritualism: Its Quest to Become a Science Creative Works

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Modern Spiritualism: Its Quest to Become A Science Creative Works 2021 Modern Spiritualism: Its Quest to Become A Science John Haller Jr Follow this and additional works at: https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/histcw_ms Copyright © 2020, John S. Haller, Jr. All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN (print): 9798651505449 Interior design by booknook.biz This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Creative Works at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Modern Spiritualism: Its Quest to Become A Science by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Modern Spiritualism: Its Quest to Become A Science By John S. Haller, Jr. Copyright © 2020, John S. Haller, Jr. All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN (print): 9798651505449 Interior design by booknook.biz Spiritualism, then, is a science, by authority of self-evident truth, observed fact, and inevitable deduction, having within itself all the elements upon which any science can found a claim. (R. T. Hallock, The Road to Spiritualism, 1858) TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 Chapters 1. Awakening 11 2. Rappings 41 3. Poughkeepsie Seer 69 4. Architect of the Spirit World 95 5. Esoteric Wisdom 121 6. American Portraits 153 7. -

Hours with the Ghosts, Or, Nineteenth Century Witchcraft : Illustrated

&* \3 1<* .• J& ^ *ti ._$& - C> * *> v .'* v %. & «\ : - ^ • ^ r o. **?CT* A • Av 0* »°JL** "*b * . 4* V ,>^>- V%T' , >*."• xWV/,.aA :- ^d* • ,*- **'*0n« .'j w e$^ ,v^. .c, tfv -.- <r% i^^ V S\ r «^ ••«•" ^ ** ' V ^ ** \& ..**' t?' .'J&l-*** V > G°* .^>>o ^o< • * ^ **•:? 0* • L^L'* '^TVi* A o, **T.T« A <> * *£_ %\ % 4» ^-\y V^-'V \y*l*z>\# Sir.- ^% ^ r-\ ..«, A* 1 • o > Ao * ^ i> v;^>°u>;; ^\^^'^, f-' y A C *• #°+ / aO v*^?r- # -^ ,» *. "%/' % ^ i^ /js |: V** :*»t ;*; — Hours With the Ghosts OR NINETEENTH CENTURY WITCHCRAFT Ltf ILLUSTRATED INVESTIGATIONS Phenomena of Spiritualism and Theosophy Henry Ridgely' Evans The first duty we owe to the world is Truth—all the Truth—nothing but the Truth. "Ancient Wisdom." CHICAGO LAIRD & LEE, PUBLISHERS £681 LZ 100 rA *<V Entered according to act of Congress, in the year eighteen hundred and ninety-seven. By WILLIAM H. LEE, In the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington. TO MY WIFE — ' " It is no proof of wisdom to refuse to examine certain phe- nomena because we think it certain that they are impossible, as if our knowledge of the universe were already completed. ' —Prof. Lodge. ' ' The most ardent Spiritist should welcome a searching in- quiry into the potential faculties of spirits still in the flesh. Until we know more of these, those other phenomena to which he appeals must remain unintelligible because isolated, and are likely to be obstinately disbelieved because they are impos- sible to understand." F. W. H. Myers: "Proceedings of the Societyfor Psychical Research^ Part XVIII, April, 1891. TABLE OF CONTENTS. -

The Forbidden Game

The Forbidden Game The Psychedelic Library Homepage Books Menu Page The Forbidden Game A Social History of Drugs Brian Inglis http://www.druglibrary.org/schaffer/lsd/inglis.htm (1 of 2)4/15/2004 11:52:52 AM The Forbidden Game Contents Introduction 1 Drugs and Shamanism 2 Drugs and the Priesthood 3 The Impact of Drugs on Civilisation 4 The Impact of Civilisation 5 Spirits 6 The Opium Wars 7 Indian Hemp 8 The Poet's Eye 9 Science 10 Prohibition 11 The International Anti-Drug Campaign 12 Heroin and Cannabis 13 The Collapse of Control Postscript Acknowledgements Sources Bibliography The Forbidden Game ©1975 by Brian Inglis Published by Charles Scribner's Sons, New York ISBN 0-684-14428-X Send e-mail to The Psychedelic Library: [email protected] The Psychedelic Library | Books Menu Page http://www.druglibrary.org/schaffer/lsd/inglis.htm (2 of 2)4/15/2004 11:52:52 AM The Forbidden Game - Introduction The Psychedelic Library Homepage Books Menu Page The Forbidden Game Brian Inglis Introduction WE TAKE DRUGS FOR TWO MAIN REASONS; EITHER TO RESTORE ourselves to the condition we regard as normal—to cure infections, and to take away pain; or to release us from normality—to enable us to feel more lively, or more relaxed; to alter our mood, or our perceptions. It is with this second category (of drug use, not of drugs; the drugs themselves may be the same) that I am concerned. For some reason, there is no generally accepted colloquial description. 'Narcotic' is quite familiar, but it has acquired a pejorative tinge, and in any case it should properly be used only about a drug used to induce drowsiness or stupor. -

Theoria to Theory

THEORIA TO THEORY VOLUME 8 NUMBER 1 Copied from this pdf at the EP’s web site The original is this pdf at the HathiTrust website For Copyright provisions, see the next page File dated 2017-09-14 15:28:52 Theoria to theory; an international journal of science, philosophy, and contemplative religion. London, Gordon and Breach Science Publishers. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015024591490 Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike http://www.hathitrust.org/access_use#cc-by-nc-sa-4.0 This work is protected by copyright law (which includes certain exceptions to the rights of the copyright holder that users may make, such as fair use where applicable under U.S. law), but made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike license. You must attribute this work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). This work may be copied, distributed, displayed, and performed - and derivative works based upon it - but for non-commercial purposes only (if you are unsure where a use is non-commercial, contact the rights holder for clarification). If you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under the same or similar license to this one. Please check the terms of the specific Creative Commons license as indicated at the item level. For details, see the full license deed at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0. THEORIA to theory VOLUME 8, NUMBER 1 (1974) CONTENTS Editorial -

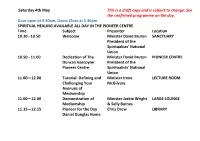

Saturday 4Th May Open Week Draft Programme

Saturday 4th May This is a draft copy and is subject to change. See the confirmed programme on the day. Door open at 9.30am, Doors Close at 5.30pm SPIRITUAL HEALING AVAILABLE ALL DAY IN THE PIONEER CENTRE Time Subject Presenter Location 10.30 –10.50 Welcome Minister David Bruton SANCTUARY President of the Spiritualists' National Union 10.50 - 11.00 Dedication of The Minister David Bruton PIONEER CENTRE Duncan Gascoyne President of the Pioneer Centre Spiritualists' National Union 11.00—12.00 Tutorial: Defining and Minister Irene LECTURE ROOM Challenging Your McGilvary Avenues of Mediumship 11.00—12.00 Demonstration of Minister Jackie Wright LARGE LOUNGE Mediumship & Sally Barnes 11.15—12.15 Pioneer for the Day Chris Drew LIBRARY Daniel Dunglas Home 12.15 - 1.15 Demonstration of Minister Colin Bates LECTURE ROOM Mediumship and Lynn Parker 11.30 - 12.30 Trance Demonstration Minister Judith Seaman SANCTUARY 12.30—1.30 An appointment with Libby Clarke OSNU LARGE LOUNGE Dr. James Trance Healing 12.30—1.30 The Saturday debate - Minister David R LIBRARY Search for the True Bruton, Minister Jackie message of Spiritualism Wright & John Blackwood OSNU 12.45—1.45 Demonstration of GORDON HIGGINSON SANCTUARY Mediumship Scholarship Students 1.30 - 2.30 Trance Healing Minister Steven Upton LECTURE ROOM Demonstration 2.45 - 3.45 Lecture: Shamanic soul Maureen Murnan LECTURE ROOM 2.00 - 300 Demonstration of Penny Hayward & Julie LIBRARY Mediumship Grist 2.15 - 315 "Branching out - Alv Hirst GARDEN Subject to philosophy to take us weather further.' 2.00—3.00 -

Anthropology of the Weird L

Anthropology of the Weird l Ethnographic Fieldwork and Anomalous Experience by Jack Hunter mmersing oneself in another culture is always going to be a strange experience, and most anthropologists will be expecting to encounter different ways of thinking about Ithe world when they first embark on their fieldwork. What they do not necessarily expect, however, is to start experiencing the world around them differently; to begin seeing and feeling things that, from the perspective of western science, simply cannot be possible. We might class such experiences, therefore, as “anomalous” because they do not sit comfortably with our rational scientific view of the world, but that is not to say such experiences are considered anomalous by the ethnographer’s host culture. Indeed while such experiences may not be particularly common or widespread amongst the population of the host culture, they may yet have a 244 DARKLORE Vol. 6 Anthropology of the Weird 245 place, and significant meaning, within that culture’s broader world- of human personality after death. Belief in spiritual beings was to view. In other cultures, therefore, experiences such as telepathic become the central theme of Tylor’s highly respected anthropological communication between two individuals, predicting the future theory for the origin of religion, and it has been suggested that his in dreams, seeing the dead reanimate, witnessing an apparition, ideas developed in parallel with his researches into the Spiritualist communicating with spirits through entranced mediums, or being movement.2 Tylor saw Spiritualism as a modern remnant, what he afflicted by witchcraft (amongst others) may be considered entirely termed a ‘survival,’ of primitive animist beliefs and as such was keen possible. -

Natural and Supernatural: a History of the Paranormal from the Earliest Times to 1914 Online

1m5hj (Ebook pdf) Natural and Supernatural: A History of the Paranormal from the Earliest Times to 1914 Online [1m5hj.ebook] Natural and Supernatural: A History of the Paranormal from the Earliest Times to 1914 Pdf Free Brian Inglis audiobook | *ebooks | Download PDF | ePub | DOC Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #2070960 in Books White Crow Books 2012-06-11Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 9.02 x 1.18 x 5.98l, 1.69 #File Name: 1908733209528 pages | File size: 47.Mb Brian Inglis : Natural and Supernatural: A History of the Paranormal from the Earliest Times to 1914 before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Natural and Supernatural: A History of the Paranormal from the Earliest Times to 1914: 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. An Excellent Overview of the Topic; Highly recommendedBy Ileana Grams-MoogA clear and remarkably thorough history of explorations of paranormal phenomena in the West. Inglis covers this extremely large field coherently and with dispassion and accuracy. In both this book and Inglis's equally good book, Trance, the coverage of Mesmerism, hypnotism, and "magnetism", is the best I've seen. These three overlapping phenomena--or three names for the same or similar phenomena-- remain shrouded in mystery not only in their natures, but in the way they are covered or glossed over in almost all works that touch on hypnotism. Inglis gives enough detail about Mesmer and his successors, and about their work, to make it clear that there are at least two techniques involved--physical passes over the subject, and the use of voice or a shiny object to focus on to put the subject into a trance--and that they are not the same thing. -

Georgiana Houghton Spirit Drawings Georgiana Houghton Spirit Drawings

GEORGIANA HOUGHTON SPIRIT DRAWINGS GEORGIANA HOUGHTON SPIRIT DRAWINGS Simon Grant, Lars Bang Larsen and Marco Pasi edited by Ernst Vegelin van Claerbergen and Barnaby Wright First published to accompany GEORGIANA HOUGHTON: SPIRIT DRAWINGS The Courtauld Gallery, London, 16 June – 11 September 2016 Organised in collaboration with Monash University Museum of Art CONTENTS The Courtauld Gallery is supported by the Higher Education Funding Council for England (hefce) 6 Director’s Foreword 8 “Works of art without parallel in the world” Georgiana Houghton’s Spirit Drawings Copyright © 2016 simon grant and marco pasi Texts copyright © the authors All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any storage or retrieval system, without the 24 Spectres of Art prior permission in writing from the copyright holder and publisher. lars bang larsen and marco pasi isbn 9781 911300 02 1 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library 34 CATALOGUE Produced by Paul Holberton publishing 89 Borough High Street, London se1 1nl 36 Catalogue Introduction www.paul-holberton.net Designed by Laura Parker ernst vegelin van claerbergen and barnaby wright Printing by Gomer Press, Llandysul front cover: Detail of cat. 7, The Eye of God; frontispiece: Detail of cat. 19, The Eye of the Lord; page 7: Detail of cat. 4, 82 List of Works Flower of William Harman Butler; page 8: Detail of cat. 12, The Risen Lord; page 17: Detail of verso of cat. 15, The Eye of the Lord; page 24: Detail of cat.