Revolutionary Years

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The New Link Easter 2013

Georgian 69 PeCarsel Setreaetn. Teel: r67s 1 0747 (We have moved 3 Doors Down) Dry Cleaning • Alterations • Launderette DRY CLEANING Cost per Item Tie . .€4.00 Cost per Item Shirt . .€4.50 Trousers . .€6.50 Service Wash Jacket . .€6.50 5kg . €11.00 Suit 2 Piece . .€13.00 8kg . €16.00 Suit 3 Piece . .€16.00 10kg . €20.00 Skirt . .€6.50 15kg . €30.00 Overcoat . .€12.00 Duvet (Double) . €18.00 Dress . .€12.00 Duvet (Single) . €14.00 Jumper . .€4.50 Duvet (King Size) . €22.00 Open: Monday to Friday 8.30 a.m. – 6 p.m. Saturday 8.30 a.m. – 5 p.m. DID YOU KNOW WE STOCK: Weschem Buster Cleaning Products – a guaranteed Irish Company. Ask Alan for details Wishing the Community a Very Happy Easter from Albert, Family and Staff New Link 2 THE NEW LINK CELEBRATING EASTER HOPE CONTENTS Page Celebrating Easter Hope .................................3 As you read this, Lent is drawing to a close and we look forward to the hope Ghosts of the Lancaster by and assurance of Easter. The name Lent comes from the old word to Denis Ranaghan ...........................................4-5 lengthen, because the approach to Easter is marked by longer days and The Accident by Tony Rooney ........................7 brighter evenings. As Easter comes early this year, the longer days are Dr. O’Cleirigh Medical Matters .......................8 particularly noticeable and welcome. Christy Bolton’s Retirement / Homelessness by Ann Curran .........................9 This year the post-Christmas gloom seemed longer and more miserable Horoscopes for Easter ...................................11 than usual. Apart from the dark mornings and evenings, the continuing South Docks Festival 2013 ............................12 economic and employment difficulties have been pressing down on many The Floating Chapel in Ringsend people. -

Conference Programme

@LIBERconference #LIBER2019 48th LIBER Annual Conference Research Libraries Trinityfor College Society Dublin, Ireland 26-28 June 2019 consortium of national & university libraries While the world benefits from what’s new, IEEE can focus you on what’s next. IEEE Xplore can power your research and help develop Esploro new ideas faster with access to trusted content: • Journals and Magazines • eLearning The Library at the • Conference Proceedings • Analytics Solutions • Standards • Plus content from Heart of Research • eBooks select partners LEVERAGE LIBRARY EXPERTISE FOR MANAGING IEEE Xplore® Digital Library Information Driving Innovation AND EXPOSING INSTITUTIONAL RESEARCH See how IEEE Xplore can add value to your institution’s research collection. Learn More innovate.ieee.org Connect with IEEE Xplore One place for all Intelligent capture of research output data from internal & and data, across all external sources disciplines Improve visitor experience by providing real-time occupancy data Metadata Automated Analysis & and booking services. enrichment for update of measurement improved researcher profiles of research discoverability performance 2 N°1 mobile services for libraries Learn More: http://bit.ly/EXLEsploro www.affluences.com 48th LIBER Annual Conference Research Libraries for Society Trinity College Dublin, the University of Dublin 26-28 June 2019 @LIBERconference #LIBER2019 5 Table of Contents 4 LIBER 2019 Main Programme at a Glance 6 Welcome from the President of LIBER 8 Welcome to Trinity College Dublin 10 Welcome to Ireland 11 Venue Information 14 Conference Essentials 15 Social Programme 22 Pre-Conference Programme 25 Annual Conference Programme 39 Exhibition and Posters 41 Workshops 59 Abstracts and Presenter Profiles 153 Invitation to LIBER 2020 154 LIBER Annual Conference Fund 155 LIBER Award for Library Innovation 160 Exhibition Floor Plan 162 LIBER Organisation 166 Acknowledgements & Thanks All contents (text and images), except where otherwise noted, are licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence. -

A Few Words from the Editor Welcome to Our Winter Issue of Irish Roots

Irish Roots 2015 Number 4 Irish Roots A few words from the editor Welcome to our Winter issue of Irish Roots. Where Issue No 4 2015 ISSN 0791-6329 on earth did that year disappear to? As the 1916 commemorations get ready to rumble CONTENTS we mark this centenary year with a new series by Sean Murphy who presents family histories of leaders of the 1916 Easter Rising, page 6. We 4 News introduce another fascinating series featuring sacred sites of Ireland and we begin with a visit to the Hill of Uisneach in County Westmeath, a place of great significance in 5 And Another Thing the history and folklore of Ireland, page 8. Patrick Roycroft fuses genealogy and geology on page 16 and Judith Eccles Wight helps to keep you on track with researching your railroad ancestors 6 1916 Leaders Family Histories in the US, page 22. We remember the Cullen brothers who journeyed from the small townland of Ballynastockan in Co. Wicklow to Minneapolis, US, 8 Sacred Sites Of Ireland bringing with them their remarkable stone cutting skills, their legacy lives on in beautiful sculptures to this day and for generations to come, page 24. Staying in Co. Wicklow we share the story of how the lost WW1 medals of a young 10 Tracing Your Roscommon Ancestors soldier were finally reunited with his granddaughter many years later, page 30. Our regular features include, ‘And another Thing’ with Steven Smyrl on the saga of the release of the Irish 1926 census, page 5. James Ryan helps us to 12 ACE Summer Schools trace our Roscommon ancestors, page 10 and Claire Santry keeps us posted with all the latest in Irish genealogy, page 18. -

“This Cemetery Is a Treacherous Place”. the Appropriation of Political, Cultural and Class Ownership of Glasnevin Cemetery, 1832 to 1909

Studi irlandesi. A Journal of Irish Studies, n. 9 (2019), pp. 251-270 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.13128/SIJIS-2239-3978-25516 “This cemetery is a treacherous place”. The Appropriation of Political, Cultural and Class Ownership of Glasnevin Cemetery, 1832 to 1909 Patrick Callan Trinity College Dublin (<[email protected]>) Abstract: Dublin’s Glasnevin Cemetery became a focus of nationalist com- memoration after 1832. The Irish diaspora in America celebrated it as the resting place of nationalist heroes, including Parnell, O’Connell and others linked with Irish Catholicity or culture. American news- papers reported on commemorations for the Manchester Martyrs and Parnell. The Dublin Cemeteries Committee (DCC) managed the cemetery. In the early 1900s, the DCC lost a political battle over who should act as guardian of the republican tradition in a tiny ar- ea of political property within the cemetery. A critical sequence of Young Irelander or Fenian funerals (Charles Gavan Duffy, James Stephens, and John O’Leary) marked the transfer of authority from the DCC to advanced nationalists. The DCC’s public profile also suffered during the 1900s as Dublin city councillors severely criti- cised the fees charged for interments, rejecting the patriarchal au- thority of the cemetery’s governing body. Keywords: Commemoration, Diaspora, Glasnevin Cemetery, Parnell 1. Introduction Dublin’s Glasnevin Cemetery opened in 1832 as an ideal of the nine- teenth-century garden cemetery. Daniel O’Connell’s Catholic Association successfully worked to repeal the surviving Penal Laws against Irish Catho- lics, leading to Catholic Emancipation in 1829. In part, the campaign had focused on the need for new regulations to allow for the establishment of Catholic cemeteries such as Glasnevin, formally known as Prospect Cem- etery. -

Westland Row

Westland Row Origins of the Parish, Church and School In this section we set out a brief history of the origins and development of Westland Row:- The Parish The Church of Saint Andrew The School founded by The Christian Brothers 1 Table of Contents 1 THE PARISH ........................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Dublin - the walled city .............................................................................................................. 4 1.2 Outside the walls ......................................................................................................................... 5 1.3 The Parish takes shape ................................................................................................................. 8 1.4 The real property crash ................................................................................................................ 9 1.5 From Trinity to Ringsend ............................................................................................................ 12 1.6 Dublin to Kingstown Rail terminal ............................................................................................. 14 2 ST. ANDREW’S CHURCH ...................................................................................................................... 16 2.1 Townsend Street ........................................................................................................................ 16 2.2 New Home in Westland -

ITA/206 Turner Collection: Micheál Mac Liammóir Papers

Irish Theatre Archive: ITA/206 Turner Collection/Mac Liammoir Papers DUBLIN CITY ARCHIVES ITA/206 Turner Collection: Micheál Mac Liammóir Papers Irish Theatre Archive at Dublin City Archives Descriptive List by Dr. Mary Clarke Irish Theatre Archive @ Dublin City Archives Dublin City Library and Archive 138-144 Pearse Street, Dublin 2 1 Irish Theatre Archive: ITA/206 Turner Collection/Mac Liammoir Papers Tel: 00 353-1-674 4996/4997 Email: [email protected] 2 Irish Theatre Archive: ITA/206 Turner Collection/Mac Liammoir Papers CATALOGUING SYSTEM FOR TURNER COLLECTION/MAC LIAMMOIR ARCHIVES 01: Programmes/Gate 3 02: Programmes/not Gate 53 03: Playbills 57 04: Playscripts 61 05: Scripts in Irish language 63 06: Press cuttings 65 07: Photographs 68 08: Set designs 78 09: Costume designs 84 10: Graphic designs 89 11: Correspondence 91 12: Notes 102 13: Publications 107 14: Miscellaneous 110 3 Irish Theatre Archive: ITA/206 Turner Collection/Mac Liammoir Papers Irish Theatre Archive Turner Collection: Micheál Mac Liammóir Papers ITA/206/1: Programmes/ Dublin Gate Theatre 4 Irish Theatre Archive: ITA/206 Turner Collection/Mac Liammoir Papers Ref No: ITA/206/01/01 Document type: Programme Date: 28 October 1928 Production: The Hairy Ape Author: Eugene O’Neill Producer/Director: Hilton Edwards Stage Design: Micheal Mac Liammóir/executed by Dom Bowe Costume Design: Micheal Mac Liammóir Theatre: Peacock Inserts: Press cutting, Irish Times, 29 October 1928 AFH Ref: 2 Ref No: ITA/206/01/02 Document type: Programme Date: 18 November 1928 Production: -

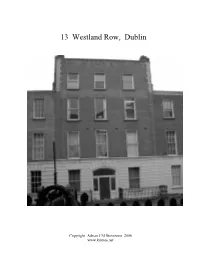

13 Westland Row, Dublin

13 Westland Row, Dublin Copyright Adrian J M Stevenson 2006 www.kintree.net 1847 (above), detail from Ordnance Survey map. This image is taken from 'The 1851 Dublin City Census' CD-ROM and online publication at www.irishorigins.com. It is reproduced with the permission of Eneclann Ltd and Origins.net. 2006 (below). This image is taken from online publication at www.tcd.ie. It is reproduced with the permission of Trinity College Dublin and ERA-Maptec Ltd. 13 Westland Row, Dublin: its occupants from 1842 to 2006 page 3 of 10 Introduction Westland Row was laid out as a street in 17731; maps of 17802 and 17973 show the Vice Provost’s Garden of Trinity College extending to the very carriageway of Westland Row. The freehold of No 13 Westland Row can be shown to belong to Trinity College from at least 19094; a history of the College suggests ownership by the College at an earlier date5. Possibly the property falls within the limits of the original grant of land to the College6. The street was first known as Westland’s Row, and was not recorded as Westland Row until 17927. Building is thought to have started at the southern end, at Westland Row’s junction with Lincoln Place (earlier Park Street, earlier Patricks Well Lane). Research into earlier years is complicated by a re-numbering of Westland Row in 1841, probably reflecting substantial reconstruction. This re-numbering appears to have remained unaltered in subsequent years: the western side of the street is numbered consecutively, odd and even, from 1 to 32, starting from the northern end (Pearse Street, earlier Great Brunswick Street, earlier Moll’s Lane, before drastic widening and extension by the Wide Streets Commission). -

Anne Yeats Gift, 1996 (Fonds)

Anne Yeats gift (1996) National Gallery of Ireland: Yeats Archive IE/NGI/Y1 Anne Yeats gift, 1996 (fonds) 1. Identity statement area ................................................................................................ 6 2. Context area ................................................................................................................ 6 3. Content and structure area ........................................................................................... 7 4. Conditions of access and use ........................................................................................ 8 5. Allied materials area .................................................................................................... 8 6. Description control area ............................................................................................... 8 1. Anne Yeats’s catalogues to the collection .......................................................................... 10 Jack Butler Yeats archives (sub-fonds) 1. Identity statement area .............................................................................................. 12 2. Context area .............................................................................................................. 12 3. Content and structure area ......................................................................................... 14 4. Allied materials area .................................................................................................. 15 1. Original art by Jack Butler -

Patrick Pearse

Patrick Pearse Memorial Discourse Trinity Monday 11 April, 2016 Dr Anne Dolan Associate Professor in Modern Irish History 1 Provost, Fellows, Scholars, Colleagues, and Friends, I cannot quite decide if Patrick Pearse would be appalled or delighted to be the subject of a Trinity Monday discourse. No doubt he would be overjoyed to be keeping company with Robert Emmet, Thomas Davis and Theobald Wolfe Tone; he would probably be content to join his old Gaelic League colleague, Douglas Hyde again, and maybe even gratified by the kind of republicanism that came after him in Mairtin Ó Cadhain.1 He will be testy at best with Edmund Burke, downright unpleasant with Edward Carson, and it is bound to get nasty with Luce, with Joly, men who were on this side, defending these walls, during Easter week 1916.2 Provost Mahaffy’s outrage will certainly please him, because all the certainties of Trinity that Mahaffy stood for are gone if ‘a man called Pearse’, as Mahaffy once dismissed him, gets his discourse, gets to be spoken of, on this day, in here.3 If there is a place somewhere in the extremities of the heavens for the recipients of Trinity discourses we are about to barge in with an unlikely and, for most there, an unwelcome guest. We are about to start a row; so don’t be surprised if a few chairs get thrown. You see, Pearse is just not a Trinity man, at least not in any obvious or usual sense. Good Trinity men, and they usually are men when it comes to discourses, are honoured for their scholarship, their service, their life’s work shaped in or by or for this College. -

Westland Row Dublin 2

WESTLAND ROW DUBLIN 2 WESTLAND ROW DUBLIN 2 The Ideal HQ Building WESTLAND ROW DUBLIN 2 WESTLAND ROW DUBLIN 2 10,894 sq ft Carefully restored period 2.7m ground to Feature glazed atrium Grade A building with new build floor ceiling heights linking period and Office Building office extension modern Less than 100 metres 200 metres from 700 metres from Less than 1km from from Pearse Street Trinity University Grafton Street Grand Canal Dock DART Station WESTLAND ROW MARLBOROUGH ST GARDINER ST L CONNOLLY O WER STATION RNELL ST PA AMIENS STREET BUS STATION LUAS AD Y STREET HENR ALL RO OWER CUSTOM LUAS GUILD STREET W CAPEL STREET ABBEY ST L HOUSE Y STREET MAR LUAS CUSTOM HOUSE QUAY EAST 3 ABBEY ST MIDDLE AY Arena EDEN QU R I V E R L I F F E Y GEORGE'S QUAY RA STREET RA TA AY CITY QUAY ABBEY ST UPPER BURGH QU ALK TARA STREET S W OR STATION CHEL SIR JOHN ROGERSON’S QU BA D'OLIER ST AY Y RIVER LIFFEY SIR JOHN ROGERSON’S QU ASTON QUA AY Y LOWER ORMOND QUA TOWNSEND STREET Ri ve r L iff e y Ri ve r L i AY f f e y AY ON QU 6 min ORMOND QU WELLINGT ET INN'S QUAY PEARSE STREET AY Walk ESSEX QU MERCHANTS QU AY AY WOOD QU WESTLAND ROW BENSON STRE HANOVER QU DUBLIN 2 3 min AY PEARSE STREET Walk BORD GÁIS TRINITY AY G R A N DAME ST THEATRE D COLLEGE C A N A L PEARSE STREET STATION DUBLIN GRAND CANAL QU ESTATE PEARSE STREET WESTLAND ROW NASSA DUBLIN 2 CKEN STREET U STREET MA FENIAN ST FRANCES STREET T ON STREET MERRION SQ Shelbourne Park W STREET Greyhound GRAFT LO WSON STREET TRICK STREE TRICK WER GRAND CANAL ST Stadium UARE N DA PA BARRO ARE STREET MERRION GRAND CANAL KILD LO SQUARE WER MOUNT ST DOCK STATION ST STEPHENS GREEN NORTH ME RRION SQUARE . -

138 Pearse Street, Dublin 2 Tel: 677 5559 Fax: 677 0684

Georgian 69 PeCarsel Setreaetn. Teel: r67s 1 0747 (We have moved 3 Doors Down) Dry Cleaning • Alterations • Launderette DRY CLEANING Cost per Item Tie . .€4.00 Cost per Item Shirt . .€3.00 Trousers . .€6.50 Service Wash Jacket . .€6.50 5kg . €11.00 Suit 2 Piece . .€13.00 8kg . €16.00 Suit 3 Piece . .€18.00 10kg . €21.00 Skirt . .€6.50 15kg . €31.00 Overcoat . .€12.00 Duvet (Double) . €14.00 Dress . .€12.00 Duvet (Single) . €14.00 Jumper . .€4.50 Duvet (King Size) . €16.00 Open: Monday to Friday 8.30 a.m. – 6 p.m. Saturday 8.30 a.m. – 5 p.m. ASK ABOUT OUR NEW LOYALTY CARD Wishing the Community a Very Happy Christmas and a Peaceful New Year from Albert, Family and Staff New Link 2 THE NEW LINK Change and Continuity Mark Another Year CONTENTS Page Change and Continuity Mark Another Year ....3 A pretty good summer and a long and mild autumn have made the passing of the year Legal and Correct by Tony Rooney ................5 St. Andrew’s Day Centre News .......................7 seem a little slower than usual. But it seems that Christmas has crept up on us, and St. Andrew’s Resource Centre / 2014 is about to join all our yesterdays, fading into memory. Cyber Links ......................................................8 But each year is worthy of its own reflection. We can recall and relive the happy An Irish Clown – A History by Johnnie ...........9 times and events of 2014 that have been life-giving for us. And we can revisit and The Loneliest Christmas by Denis Ranaghan ....11 process those experiences which have tested us, and forced us to acknowledge how Nobel Laureates Visit Pearse Street .............12 fragile our lives are, and how uncertain our plans. -

Yeats Notes 2014

YEATS LOVE POLITICS LIFE ART Cian Hogan English Notes 2014 1 Cian Hogan English Notes 2014 Yeats stands like a colossus on the world’s literary landscape. His influence extends to nearly every facet of Irish political and cultural identity. Since his death, Yeats’s work has been viewed as nationalistic, occultist, radically right wing, modern, romantic and postcolonial. He is a very difficult poet to interpret and such varied critical opinions of his poetry stem in large part from the diverse and complex nature of his life. Yeats looked to the people and events of his time to provide him with the raw material for his poetry. He had a long and, for the most part, unrequited love affair with the beautiful and ardent patriot, Maud Gonne. He became a leading figure in the European esoteric movement, was a founding member of the Abbey Theatre and his wife was a clairvoyant who communicated with the spirit world. Yet despite the poet’s obsession with the afterlife, he was also deeply engaged with the political reality that confronted him in his native country. In fact, Yeats, more than any other writer of his day, sought to influence the course of his country’s destiny through his writing. And influence it he did. At various points in his life he attacked British rule, the narrow-mindedness of his fellow Irishmen and the democratic institutions of the postcolonial government. Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of Yeats’s career is his refusal to give in to the inevitability of old age. Some of his most insightful and profound poetry was written when the poet was nearing the end of his life.