Westland Row

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The New Link Easter 2013

Georgian 69 PeCarsel Setreaetn. Teel: r67s 1 0747 (We have moved 3 Doors Down) Dry Cleaning • Alterations • Launderette DRY CLEANING Cost per Item Tie . .€4.00 Cost per Item Shirt . .€4.50 Trousers . .€6.50 Service Wash Jacket . .€6.50 5kg . €11.00 Suit 2 Piece . .€13.00 8kg . €16.00 Suit 3 Piece . .€16.00 10kg . €20.00 Skirt . .€6.50 15kg . €30.00 Overcoat . .€12.00 Duvet (Double) . €18.00 Dress . .€12.00 Duvet (Single) . €14.00 Jumper . .€4.50 Duvet (King Size) . €22.00 Open: Monday to Friday 8.30 a.m. – 6 p.m. Saturday 8.30 a.m. – 5 p.m. DID YOU KNOW WE STOCK: Weschem Buster Cleaning Products – a guaranteed Irish Company. Ask Alan for details Wishing the Community a Very Happy Easter from Albert, Family and Staff New Link 2 THE NEW LINK CELEBRATING EASTER HOPE CONTENTS Page Celebrating Easter Hope .................................3 As you read this, Lent is drawing to a close and we look forward to the hope Ghosts of the Lancaster by and assurance of Easter. The name Lent comes from the old word to Denis Ranaghan ...........................................4-5 lengthen, because the approach to Easter is marked by longer days and The Accident by Tony Rooney ........................7 brighter evenings. As Easter comes early this year, the longer days are Dr. O’Cleirigh Medical Matters .......................8 particularly noticeable and welcome. Christy Bolton’s Retirement / Homelessness by Ann Curran .........................9 This year the post-Christmas gloom seemed longer and more miserable Horoscopes for Easter ...................................11 than usual. Apart from the dark mornings and evenings, the continuing South Docks Festival 2013 ............................12 economic and employment difficulties have been pressing down on many The Floating Chapel in Ringsend people. -

Draft Dublin City Development Plan 2016-2022 Record of Protected Structures - Volume 4 DRAFT Record of Protected Structures

Draft Dublin City Development Plan 2016-2022 Record of Protected Structures - Volume 4 DRAFT Record of Protected Structures Ref Number Address Description RPS_1 7-8 Abbey Street Lower, Dublin 1 Veritas House RPS_2 9 Abbey Street Lower, Dublin 1 Licensed premises. (Return - 108 Marlborough Street) RPS_39cAbbey Street Lower, Dublin 1 Dublin Central Mission RPS_410Abbey Street Lower, Dublin 1 Commercial premises RPS_5 12b Abbey Street Lower, Dublin 1 TSB Bank (former Dublin Savings Bank) RPS_6 Abbey Street Lower, Dublin 1 Ormond Quay and Scots Presbyterian Church. RPS_735Abbey Street Lower, Dublin 1 CIE offices RPS_8 36-38 Abbey Street Lower, Dublin 1 Hotel (Wynn's) RPS_946Abbey Street Middle, Dublin 1 Upper floors RPS_10 47 Abbey Street Middle, Dublin 1 House RPS_11 48 Abbey Street Middle, Dublin 1 House RPS_12 50 Abbey Street Middle, Dublin 1 Georgian-style house RPS_13 51 Abbey Street Middle, Dublin 1 Georgian-style house RPS_14 59 Abbey Street Middle, Dublin 1 Georgian-style house/commercial premises. RPS_15 69 Abbey Street Middle, Dublin 1 Upper floors of commercial premises; faience surrounding central pedimented Venetian-type window; faience parapet mouldings RPS_16 70 Abbey Street Middle, Dublin 1 Upper floors of commercial premises; faience surrounding central pedimented Venetian-type window; faience parapet mouldings RPS_17 78 Abbey Street Middle, Dublin 1 The Oval licensed premises - façade only RPS_18 87-90 Abbey Street Middle, Dublin 1 Independent House, including roof and roof pavilions RPS_19 94-96 Abbey Street Middle, Dublin -

Conference Programme

@LIBERconference #LIBER2019 48th LIBER Annual Conference Research Libraries Trinityfor College Society Dublin, Ireland 26-28 June 2019 consortium of national & university libraries While the world benefits from what’s new, IEEE can focus you on what’s next. IEEE Xplore can power your research and help develop Esploro new ideas faster with access to trusted content: • Journals and Magazines • eLearning The Library at the • Conference Proceedings • Analytics Solutions • Standards • Plus content from Heart of Research • eBooks select partners LEVERAGE LIBRARY EXPERTISE FOR MANAGING IEEE Xplore® Digital Library Information Driving Innovation AND EXPOSING INSTITUTIONAL RESEARCH See how IEEE Xplore can add value to your institution’s research collection. Learn More innovate.ieee.org Connect with IEEE Xplore One place for all Intelligent capture of research output data from internal & and data, across all external sources disciplines Improve visitor experience by providing real-time occupancy data Metadata Automated Analysis & and booking services. enrichment for update of measurement improved researcher profiles of research discoverability performance 2 N°1 mobile services for libraries Learn More: http://bit.ly/EXLEsploro www.affluences.com 48th LIBER Annual Conference Research Libraries for Society Trinity College Dublin, the University of Dublin 26-28 June 2019 @LIBERconference #LIBER2019 5 Table of Contents 4 LIBER 2019 Main Programme at a Glance 6 Welcome from the President of LIBER 8 Welcome to Trinity College Dublin 10 Welcome to Ireland 11 Venue Information 14 Conference Essentials 15 Social Programme 22 Pre-Conference Programme 25 Annual Conference Programme 39 Exhibition and Posters 41 Workshops 59 Abstracts and Presenter Profiles 153 Invitation to LIBER 2020 154 LIBER Annual Conference Fund 155 LIBER Award for Library Innovation 160 Exhibition Floor Plan 162 LIBER Organisation 166 Acknowledgements & Thanks All contents (text and images), except where otherwise noted, are licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence. -

A Few Words from the Editor Welcome to Our Winter Issue of Irish Roots

Irish Roots 2015 Number 4 Irish Roots A few words from the editor Welcome to our Winter issue of Irish Roots. Where Issue No 4 2015 ISSN 0791-6329 on earth did that year disappear to? As the 1916 commemorations get ready to rumble CONTENTS we mark this centenary year with a new series by Sean Murphy who presents family histories of leaders of the 1916 Easter Rising, page 6. We 4 News introduce another fascinating series featuring sacred sites of Ireland and we begin with a visit to the Hill of Uisneach in County Westmeath, a place of great significance in 5 And Another Thing the history and folklore of Ireland, page 8. Patrick Roycroft fuses genealogy and geology on page 16 and Judith Eccles Wight helps to keep you on track with researching your railroad ancestors 6 1916 Leaders Family Histories in the US, page 22. We remember the Cullen brothers who journeyed from the small townland of Ballynastockan in Co. Wicklow to Minneapolis, US, 8 Sacred Sites Of Ireland bringing with them their remarkable stone cutting skills, their legacy lives on in beautiful sculptures to this day and for generations to come, page 24. Staying in Co. Wicklow we share the story of how the lost WW1 medals of a young 10 Tracing Your Roscommon Ancestors soldier were finally reunited with his granddaughter many years later, page 30. Our regular features include, ‘And another Thing’ with Steven Smyrl on the saga of the release of the Irish 1926 census, page 5. James Ryan helps us to 12 ACE Summer Schools trace our Roscommon ancestors, page 10 and Claire Santry keeps us posted with all the latest in Irish genealogy, page 18. -

Public Art in Parks Draft 28 03 14.Indd

Art in Parks A Guide to Sculpture in Dublin City Council Parks 2014 DUBLIN CITY COUNCIL We wish to thank all those who contributed material for this guide Prepared by the Arts Office and Parks and Landscape Services of the Culture, Recreation and Amenity Department Special thanks to: Emma Fallon Hayley Farrell Roisin Byrne William Burke For enquiries in relation to this guide please contact the Arts Office or Parks and Landscape Services Phone: (01) 222 2222 Email: [email protected] [email protected] VERSION 1 2014 1 Contents Map of Parks and Public Art 3 Introduction 5 1. Merrion Square Park 6 2. Pearse Square Park 14 3. St. Patrick’s Park 15 4. Peace Park 17 5. St. Catherine’s Park 18 6. Croppies Memorial Park 19 7. Wolfe Tone Park 20 8. St. Michan’s Park 21 9. Blessington Street Basin 22 10. Blessington Street Park 23 11. The Mater Plot 24 12. Sean Moore Park 25 13. Sandymount Promenade 26 14. Sandymount Green 27 15. Herbert Park 28 16. Ranelagh Gardens 29 17. Fairview Park 30 18. Clontarf Promenade 31 19. St. Anne’s Park 32 20. Father Collin’s Park 33 21. Stardust Memorial Park 34 22. Balcurris Park 35 2 20 Map of Parks and Public Art 20 22 21 22 21 19 19 17 18 10 17 10 18 11 11 9 9 8 6 7 8 6 7 2 2 5 4 5 4 1 3 12 1 3 12 14 14 15 13 16 13 16 15 3 20 Map of Parks and Public Art 20 22 21 22 21 19 19 1 Merrion Square Park 2 Pearse Square Park 17 18 St. -

“This Cemetery Is a Treacherous Place”. the Appropriation of Political, Cultural and Class Ownership of Glasnevin Cemetery, 1832 to 1909

Studi irlandesi. A Journal of Irish Studies, n. 9 (2019), pp. 251-270 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.13128/SIJIS-2239-3978-25516 “This cemetery is a treacherous place”. The Appropriation of Political, Cultural and Class Ownership of Glasnevin Cemetery, 1832 to 1909 Patrick Callan Trinity College Dublin (<[email protected]>) Abstract: Dublin’s Glasnevin Cemetery became a focus of nationalist com- memoration after 1832. The Irish diaspora in America celebrated it as the resting place of nationalist heroes, including Parnell, O’Connell and others linked with Irish Catholicity or culture. American news- papers reported on commemorations for the Manchester Martyrs and Parnell. The Dublin Cemeteries Committee (DCC) managed the cemetery. In the early 1900s, the DCC lost a political battle over who should act as guardian of the republican tradition in a tiny ar- ea of political property within the cemetery. A critical sequence of Young Irelander or Fenian funerals (Charles Gavan Duffy, James Stephens, and John O’Leary) marked the transfer of authority from the DCC to advanced nationalists. The DCC’s public profile also suffered during the 1900s as Dublin city councillors severely criti- cised the fees charged for interments, rejecting the patriarchal au- thority of the cemetery’s governing body. Keywords: Commemoration, Diaspora, Glasnevin Cemetery, Parnell 1. Introduction Dublin’s Glasnevin Cemetery opened in 1832 as an ideal of the nine- teenth-century garden cemetery. Daniel O’Connell’s Catholic Association successfully worked to repeal the surviving Penal Laws against Irish Catho- lics, leading to Catholic Emancipation in 1829. In part, the campaign had focused on the need for new regulations to allow for the establishment of Catholic cemeteries such as Glasnevin, formally known as Prospect Cem- etery. -

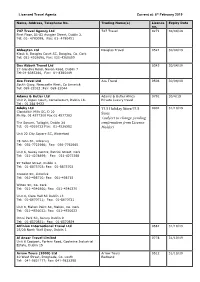

Current As of 6Th November 2008

Licensed Travel Agents Current at: 6th February 2019 Name, Address, Telephone No. Trading Name(s) Licence Expiry Date no. 747 Travel Agency Ltd 747 Travel 0271 30/04/19 First Floor, 81-82 Aungier Street, Dublin 2. Tel: 01- 4780099, Fax: 01- 4780451 Abbeytan Ltd Douglas Travel 0521 30/04/19 Kiosk 8, Douglas Court SC, Douglas, Co. Cork. Tel: 021-4365656, Fax: 021-4365659 Des Abbott Travel Ltd 0343 30/04/19 27 Glendhu Road, Navan Road, Dublin 7 Tel:01-8385266, Fax: 01-8385449 Ace Travel Ltd Ace Travel 0504 30/04/19 South Quay, Newcastle West, Co Limerick Tel: 069-22022 ;Fax: 069-22044 Adams & Butler Ltd Adams & Butler Africa 0792 30/4/19 Unit 2, Aspen Court, Cornelscourt, Dublin 18. Private Luxury travel Tel : 01 288 9433 Adehy Ltd TUI Holiday Store/TUI 0001 31/10/19 Clondalkin Mills SC, D 22 Store Ph No. 01 4577300 Fax 01 4577303 (subject to change pending The Square, Tallaght, Dublin 24 confirmation from Licence Tel: 01-4526722 Fax: 01-4526582 Holder) Unit 22 City Square SC, Waterford 78 John St., Kilkenny Tel: 056-7722966; Fax: 056-7762965 Unit 6, Savoy Centre, Patrick Street, Cork Tel: 021-4278899; Fax: 021-4273398 97 Talbot Street, Dublin 1. Tel: 01-8873703; Fax: 01-8873702 Cresent SC, Limerick Tel: 061-498710; Fax: 061-498715 Wilton SC, Co. Cork Tel: 021-4346566; Fax: 021-4346370 Unit 4, Clare Hall SC Dublin 13 Tel: 01-8670711; Fax: 01-8670721 Unit 8, Mahon Point SC, Mahon, Co. Cork Tel: 021-4536022; Fax: 021-4536023 Omni Park SC, Santry Dublin 9 Tel: 01-8570851; Fax: 01-8570854 Affinion International Travel Ltd 0681 31/10/19 25/28 North Wall Quay, Dublin 1 Al Ansar Travel Limited 0778 31/10/19 Unit 6 Coolport, Porters Road, Coolmine Industrial Estate, Dublin 15 Arrow Tours (2000) Ltd Arrow Tours 0512 31/10/19 40 West Street, Drogheda, Co. -

Here in Just a Few Minutes

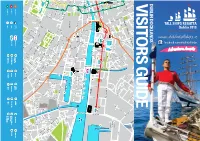

Crew NE facebook.com/dublintallships DAME STREET DAME WELLINGTON QUAY MARY STREET PARNELL S DIGGES ST UPR www.dublintallships.ie DAME LANE PARNELL SQ NTH PARNELL SQU PARNELL GEORGE'S ST FREDERICK NORTH NES LANE W W STREET UPPER CUFF GRANBY PLACE MONTAGUE LANE EAST LANE TREET DIG FADE ST FADE STR GES LANE EET G STREET LIFFEY HARDWICKE LANE E STR E ME REAT SOUTH STREET RCER ARE WEST ARE YORK STREET YORK HENRY STREET M EXCHEQUER STREET CAMDEN PLA CE ONTAGU DAME COURT DAME E L ALLEY GLOVERS STRE CROW STREET STREE LIFFEY A DRURY STREET HARDWICKE ST EET CUFFE LANE LOWER T ET EAST SQ PARNELL HA RCO URT S URT TREET C COPE STREET MARKET LONM S CASTLE MOORE STREET MOORE CROWN ALLEY CROWN DUBLIN DOCKLANDS SOUTH STREET KING WILLIAM STREET SOUT PROUD'S LANE PROUD'S GREAT DENMARK STREET TEM NORTH LOTTS EL ST EL CLARENDO MOORE LANE MOORE TRINITY ST TRINITY BACHELORS HATCH STREE HATCH H NORTH ST PLE STABLE LANE PRINCE'S STREET NORTH N STREET PLACE RUTLAND BEDFORD ROW BEDFORD ANGLESEA STREET ANGLESEA COLL NORTH GREAT GEORGE'S STREET GEORGE'S GREAT NORTH CHATHAM ST CHATHAM St. Andrew St SAINT STEPHEN'S GREEN SOUTH GREEN STEPHEN'S SAINT BALFE ST FOSTER PL FOSTER LITTON LA LITTON PARNELL JOHNSON’S CT JOHNSON’S ASTON QUAY HARRY ST HARRY - UPPER O’CONNELL EGE GR UPPER STREET O'CONNELL FLEET STREET SUFFOLK ST SUFFOLK WESTMORLAND WALK ST. STEPHENS ST. GARDINER PLAC WICKLOW ST WICKLOW HILL STREET HILL T UPPER T GREEN BACHEL ANNE ST ANNE GRAFTON STREET E WAY OR'S LEMON ST LEMON EN STREET O'CONNELL CATHEDRAL STREET LANE THOMAS BATH LANE GRENVILLE LA GRENVILLE N -

ITA/206 Turner Collection: Micheál Mac Liammóir Papers

Irish Theatre Archive: ITA/206 Turner Collection/Mac Liammoir Papers DUBLIN CITY ARCHIVES ITA/206 Turner Collection: Micheál Mac Liammóir Papers Irish Theatre Archive at Dublin City Archives Descriptive List by Dr. Mary Clarke Irish Theatre Archive @ Dublin City Archives Dublin City Library and Archive 138-144 Pearse Street, Dublin 2 1 Irish Theatre Archive: ITA/206 Turner Collection/Mac Liammoir Papers Tel: 00 353-1-674 4996/4997 Email: [email protected] 2 Irish Theatre Archive: ITA/206 Turner Collection/Mac Liammoir Papers CATALOGUING SYSTEM FOR TURNER COLLECTION/MAC LIAMMOIR ARCHIVES 01: Programmes/Gate 3 02: Programmes/not Gate 53 03: Playbills 57 04: Playscripts 61 05: Scripts in Irish language 63 06: Press cuttings 65 07: Photographs 68 08: Set designs 78 09: Costume designs 84 10: Graphic designs 89 11: Correspondence 91 12: Notes 102 13: Publications 107 14: Miscellaneous 110 3 Irish Theatre Archive: ITA/206 Turner Collection/Mac Liammoir Papers Irish Theatre Archive Turner Collection: Micheál Mac Liammóir Papers ITA/206/1: Programmes/ Dublin Gate Theatre 4 Irish Theatre Archive: ITA/206 Turner Collection/Mac Liammoir Papers Ref No: ITA/206/01/01 Document type: Programme Date: 28 October 1928 Production: The Hairy Ape Author: Eugene O’Neill Producer/Director: Hilton Edwards Stage Design: Micheal Mac Liammóir/executed by Dom Bowe Costume Design: Micheal Mac Liammóir Theatre: Peacock Inserts: Press cutting, Irish Times, 29 October 1928 AFH Ref: 2 Ref No: ITA/206/01/02 Document type: Programme Date: 18 November 1928 Production: -

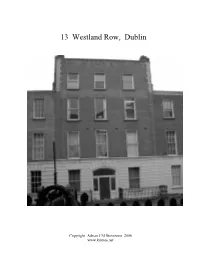

13 Westland Row, Dublin

13 Westland Row, Dublin Copyright Adrian J M Stevenson 2006 www.kintree.net 1847 (above), detail from Ordnance Survey map. This image is taken from 'The 1851 Dublin City Census' CD-ROM and online publication at www.irishorigins.com. It is reproduced with the permission of Eneclann Ltd and Origins.net. 2006 (below). This image is taken from online publication at www.tcd.ie. It is reproduced with the permission of Trinity College Dublin and ERA-Maptec Ltd. 13 Westland Row, Dublin: its occupants from 1842 to 2006 page 3 of 10 Introduction Westland Row was laid out as a street in 17731; maps of 17802 and 17973 show the Vice Provost’s Garden of Trinity College extending to the very carriageway of Westland Row. The freehold of No 13 Westland Row can be shown to belong to Trinity College from at least 19094; a history of the College suggests ownership by the College at an earlier date5. Possibly the property falls within the limits of the original grant of land to the College6. The street was first known as Westland’s Row, and was not recorded as Westland Row until 17927. Building is thought to have started at the southern end, at Westland Row’s junction with Lincoln Place (earlier Park Street, earlier Patricks Well Lane). Research into earlier years is complicated by a re-numbering of Westland Row in 1841, probably reflecting substantial reconstruction. This re-numbering appears to have remained unaltered in subsequent years: the western side of the street is numbered consecutively, odd and even, from 1 to 32, starting from the northern end (Pearse Street, earlier Great Brunswick Street, earlier Moll’s Lane, before drastic widening and extension by the Wide Streets Commission). -

RPS Ref No House No Full Address Description 1 7-8 Abbey Street Lower, Dublin 1 Veritas House 2 9 Abbey Street Lower, Dublin 1 Licensed Premises

RPS Ref No House No Full Address Description 1 7-8 Abbey Street Lower, Dublin 1 Veritas House 2 9 Abbey Street Lower, Dublin 1 Licensed premises. (Return - 108 Marlborough Street) 3 9c Abbey Street Lower, Dublin 1 Dublin Central Mission 4 10 Abbey Street Lower, Dublin 1 Commercial premises 5 12b Abbey Street Lower, Dublin 1 TSB Bank (former Dublin Savings Bank) 6 Abbey Street Lower, Dublin 1 Ormond Quay and Scots Presbyterian Church. 7 35 Abbey Street Lower, Dublin 1 CIE offices 8 36-38 Abbey Street Lower, Dublin 1 Hotel (Wynn's) 9 46 Abbey Street Middle, Dublin 1 Upper floors 10 47 Abbey Street Middle, Dublin 1 House 11 48 Abbey Street Middle, Dublin 1 House 12 50 Abbey Street Middle, Dublin 1 Georgian-style house 13 51 Abbey Street Middle, Dublin 1 Georgian-style house 8779 58 Abbey Street Middle, Dublin 1 Building 14 59 Abbey Street Middle, Dublin 1 Georgian-style house/commercial premises. 15 69 Abbey Street Middle, Dublin 1 Upper floors of commercial premises; faience surrounding central pedimented Venetian-type window; faience parapet mouldings 16 70 Abbey Street Middle, Dublin 1 Upper floors of commercial premises; faience surrounding central pedimented Venetian-type window; faience parapet mouldings 17 78 Abbey Street Middle, Dublin 1 The Oval licensed premises - façade only 18 87-90 Abbey Street Middle, Dublin 1 Independent House, including roof and roof pavilions 19 94-96 Abbey Street Middle, Dublin 1 Commercial premises 20 123-124 Abbey Street Upper, Dublin 1 Commercial premises/house 21 123a Abbey Street Upper, Dublin 1 Commercial -

69 Pearse Street. Tel: 671 0747

Georgian 69 PeCarsel Setreaetn. Teel: r67s 1 0747 Dry Cleaning • Alterations • Launderette DRY CLEANING Cost per Item Tie . .€4.00 Cost per Item Shirt . .€3.00 Trousers . .€6.50 Service Wash Jacket . .€6.50 5kg . €11.00 Suit 2 Piece . .€13.00 8kg . €16.00 Suit 3 Piece . .€18.00 10kg . €21.00 Skirt . .€6.50 15kg . €31.00 Overcoat . .€12.00 Duvet (Double) . €14.00 Dress . .€12.00 Duvet (Single) . €14.00 Jumper . .€4.50 Open: Monday to Friday 8.30 a.m. – 6 p.m. Saturday 8.30 a.m. – 5 p.m. ASK ABOUT OUR NEW LOYALTY CARD Wishing the Community a Very Happy Christmas and a Peaceful New Year from Albert, Family and Staff New Link 2 THE NEW LINK Page CHRISTMAS TIME ChrOistmNas TimEe ................................................3NTS I Don’t Know Much About Art by Rhonda .......................................................5 It’s hard to believe that Christmas is nearly upon Show The Picture by Tony Rooney .................6 us again. We had a lovely extended Autumn and Dr. O’Cleirigh’s Medical Matters .....................7 all of a sudden it’s December and the hustle and Past Nichols, the Undertakers by Gus Nichol ...................................................9 bustle is in full swing. The City has come alive with a fabulous array Personal Safety ......................................................10 of lights and colourful window displays with all the latest toys and The Last Rose by Monica Moffat .........................11 Raytown Angling Club ...................................12 gadgets for all ages. The Christmas buzz gives us all a sense of hope South Docks Festival Picture Special .................13 and cheer and helps to take our minds off the many tragic events The Ballad of Leo Fitzgerald that have taken place recently in our world.