1 the Politics of Extension of State Power in Karamoja

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Karamoja Rapid Crop and Food Security Assessment

KARAMOJA RAPID CROP AND FOOD SECURITY ASSESSMENT KAMPALA, AUGUST 2013 This Rapid Assessment was conducted by: World Food Programme (WFP) - Elliot Vhurumuku; Hamidu Tusiime; Eunice Twanza; Alex Ogenrwoth; Swaleh Gule; James Odong; and Joseph Ndawula Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) - Bernard Onzima; Joseph Egabu; Paddy Namurebire; and Michael Lokiru Office of the Prime Minister (OPM) - Johnson Oworo; Timothy Ojwi; Jimmy Ogwang; and Catherine Nakalembe Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries (MAAIF) - James Obo; and Stephen Kataama Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. 2 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 3 1.1. Background .............................................................................................................................. 3 1.2. Objectives ................................................................................................................................ 4 1.3. Methodology ........................................................................................................................... 4 1.3.1. Sampling methodology .................................................................................................... 4 1.3.2. Selection of respondents ................................................................................................ -

The Charcoal Grey Market in Kenya, Uganda and South Sudan (2021)

COMMODITY REPORT BLACK GOLD The charcoal grey market in Kenya, Uganda and South Sudan SIMONE HAYSOM I MICHAEL McLAGGAN JULIUS KAKA I LUCY MODI I KEN OPALA MARCH 2021 BLACK GOLD The charcoal grey market in Kenya, Uganda and South Sudan ww Simone Haysom I Michael McLaggan Julius Kaka I Lucy Modi I Ken Opala March 2021 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors would like to thank everyone who gave their time to be interviewed for this study. They would like to extend particular thanks to Dr Catherine Nabukalu, at the University of Pennsylvania, and Bryan Adkins, at UNEP, for playing an invaluable role in correcting our misperceptions and deepening our analysis. We would also like to thank Nhial Tiitmamer, at the Sudd Institute, for providing us with additional interviews and information from South Sudan at short notice. Finally, we thank Alex Goodwin for excel- lent editing. Interviews were conducted in South Sudan, Uganda and Kenya between February 2020 and November 2020. ABOUT THE AUTHORS Simone Haysom is a senior analyst at the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime (GI-TOC), with expertise in urban development, corruption and organized crime, and over a decade of experience conducting qualitative fieldwork in challenging environments. She is currently an associate of the Oceanic Humanities for the Global South research project based at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. Ken Opala is the GI-TOC analyst for Kenya. He previously worked at Nation Media Group as deputy investigative editor and as editor-in-chief at the Nairobi Law Monthly. He has won several journalistic awards in his career. -

Status of Karamoja Land

TENURE IN MYSTERY : Status of Land under Wildlife, Forestry and Mining Concessions in Karamoja Region, Uganda By; Margaret A. Rugadya, Herbert Kamusiime and Eddie Nsamba-Gayiiya This study was undertaken with support from TROCAIRE Uganda and Oxfam GB in Uganda to Associates Research Uganda August 2010 i About the Authors: Margaret A. Rugadya is a public policy analyst with bias to socio-economic and legal fields relating to land and natural resources management. Currently is a PhD research fellow at the University of Maastricht, the Netherlands. Herbert Kamusiime is an agricultural economist, widely experienced in socio-economic research, holding a Master degree. Currently is the Executive Director of Associates Research Uganda, a policy research trust. Eddie Nsamba-Gayiiya is a land economist, holding a Master degree and 25 years of service in the field of valuation with the Government of Uganda. Currently is the Executive Director of Consultant Surveyors and Planners, a private consultancy firm. Christine Kajumba is a research manager at Associates Research Uganda, with 6 years of coordinating the field surveys and data collection in different parts of Uganda. MAP OF KARAMOJA ii Source: Archives, 2010 iii OVERVIEW Tenure in Mystery collates information on land under conservation, forestry and mining in the Karamoja region. Whereas significant changes in the status of land tenure took place with the Parliamentary approval for degazettement of approximately 54% of the land area under wildlife conservation in 2002, little else happened to deliver this update to the beneficiary communities in the region. Instead enclaves of information emerged within the elite and political leadership, by means of which personal interests and rewards were being secured and protected. -

Trees and Livelihoods in Karamoja, Uganda

Trees and Livelihoods in Karamoja, Uganda Anthony Egeru, Clement Okia and Jan de Leeuw December 2014 This report has been produced by the World Agroforestry Centre for Evidence on Demand with the assistance of the UK Department for International Development (DFID) contracted through the Climate, Environment, Infrastructure and Livelihoods Professional Evidence and Applied Knowledge Services (CEIL PEAKS) programme, jointly managed by DAI (which incorporates HTSPE Limited) and IMC Worldwide Limited. The views expressed in the report are entirely those of the author and do not necessarily represent DFID’s own views or policies, or those of Evidence on Demand. Comments and discussion on items related to content and opinion should be addressed to the author, via [email protected] Your feedback helps us ensure the quality and usefulness of all knowledge products. Please email [email protected] and let us know whether or not you have found this material useful; in what ways it has helped build your knowledge base and informed your work; or how it could be improved. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12774/eod_hd.december2014.egeruaetal First published February 2015 © CROWN COPYRIGHT Trees forming bushlands that provide hunting grounds for young people and trees shielding a water pan in Nadunget Moroto district. Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................... iii SECTION 1............................................................................................... -

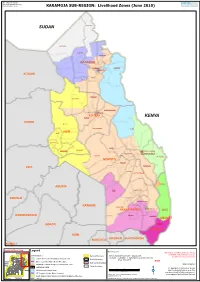

MOROTO DISTRICT: Livelihood Zones KAABONG Uganda Overview Kothoniok (! Jie �)(! Lothagam Sudan Kotido (! !

IMU, UNOCHA Uganda http://www.ugandaclusters.ug http://ochaonline.un.org KARAMOJA SUB-REGION: Livelihood Zones (June 2010) SUDAN KATHILE KARENGA KAPEDO KALAPATA KAABONG KAABONG LOYORO KAABONG TC KITGUM SIDOK LOLELIA RENGEN KACHERI NAKAPELIMORU KOTIDO TC KOTIDO KOTIDO KENYA PADER ALEREK PANYANGARA RUPA ABIM ABIM LOTUKEI LOPEI NYAKWAE MORULEM NORTHERN DIVISION NGOLERIET SOUTHERN DIVISION LOKOPO KATIKEKILE MOROTO MATANY LIRA NADUNGET LOTOME LORENGEDWAT LOROO AMURIA IRIIRI NABILATUK DOKOLO KAKOMONGOLE KATAKWI LOLACHAT NAKAPIRIPIRIT NAKAPIRIPIRIT TC AMUDAT KABERAMAIDO NAMALU MORUITA AMUDAT SOROTI KARITA AMUDAT KUMI SIRONKO KAPCHORWA BUKEDEA KAMULI Uganda Overview Legend Data Sources: This map is a work in progress. Please Sudan contact the IMU/Ocha as soon as Livelihood Zones Admin Boundaries/Centers - UBOS 2006 National Boundary possible with any corrections. Thematic - FEWSNET, FAO/District Local Government, Central and Southern Karamoja Pastoral Zone District Boundary DAO, May 2010 Draft Congo Eastern Lowland Maize Beans Rice Zone Label Sub-County Boundary (Dem. Karamoja Livestock Sorghum Bulrush Millet Zone Map Disclaimer: Rep) Parish Boundary NATIONAL PARK 010 20 40 The boundaries and names shown Kenya NE Karamoja Pastoral Zone and the designations used on this Kilometers map do not imply official endorsement NE Sorghum Simsim Maize Livestock Map Prepare: 9 June, 2010 (IMU/UNOCHA, Kampala) K or acceptance by the United Nations. South Kitgum Pader Simsim Groundnuts Sorghum Cattle Zone Updated: 10 June, 2010 Tanzania Rwanda URBAN FileUG-Livelihood-06_A3_10June2010_Karamoja -

Community Perspectives on Natural Resources and Conflict in Southern Karamoja

Save the Children in Uganda Foraging and Fighting: Community Perspectives on Natural Resources and Conflict in Southern Karamoja Elizabeth Stites Feinstein International Center, Tufts University Lorin Fries Save the Children in Uganda Darlington Akabwai Feinstein International Center, Tufts University August 2010 Foraging and Fighting: Community Perspectives on Natural Resources and Conflict in Southern Karamoja Elizabeth Stites Feinstein International Center, Tufts University Lorin Fries Save the Children in Uganda Darlington Akabwai Feinstein International Center, Tufts University August 2010 Design and Layout: Calvin R. Armstrong/Save the Children Foraging and Fighting Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 About the Feinstein International Center 3 About Save the Children in Uganda 3 Introduction 4 Methodology 4 Natural Resources for Lives and Livelihoods 7 Natural Resource Priorities 7 Demographic Differences in Natural Resource Prioritization 9 Available but Inaccessible: Barriers to Natural Resource Utilization 9 Availability of Resources 9 Accessibility of Resources 9 Reinforcing Cycles of Insecurity, Resource Distance, and Clustered Settlements 11 Natural Resource Governance 12 Gender, Natural Resources, and Survival Strategies 14 Shifts toward Foraged Resources and Resulting Governance Gaps 15 Role of the Official System 17 Natural Resource Protection 19 Natural Resource Exploitation 19 Natural Resource Protection Strategies 19 Responsibility for Resource Protection 20 Cutting Akiriket 21 Natural Resources: Drivers of Conflict? 22 Site-specific Conflict versus Conflict over Sites 23 Peace and Natural Resource Access 25 Conclusion and Recommendations 28 Conclusions 28 Recommendations 30 Sources Cited 32 Stites, Fries and Akabwai 2 Feinstein International Center and Save the Children in Uganda August 2010 Foraging and Fighting Acknowledgements The authors greatly appreciate the support and collaboration of Save the Children in Uganda. -

The State of Radio in Uganda: a 2020 Review and the New Reality of COVID-19 March 2021

March 2021 The State of Radio in Uganda: A 2020 Review and the New Reality of COVID-19 March 2021 About Internews Internews is an international nonprofit organization that empowers people worldwide with trustworthy, high quality news, and information, the ability to make informed decisions, participate in their communities, and hold power to account. For nearly 40 years, in more than 120 countries, Internews has worked to build healthy media and information environments where they are most needed. Acknowledgements This comprehensive study was carried out by Internews Regional Team from October 2020 – February 2021 under the guidance of Kenneth Okwir, Internews Uganda Country Director and Brice Rambaud, Regional Director for Sub-Saharan Africa. We are particularly grateful to the Uganda Communications Commission, media associations, and radio stations from central, western, eastern, and northern parts of the country who provided invaluable insights and inputs into the complex history and on the current state of the media sector in Uganda. Without their invaluable service to continually inform and engage communities across Uganda and the rich engagement and feedback that they provided throughout this process, this report would not have been possible. We also want to recognize the following organizations and individuals for their time, deep insights and critical feedback throughout this process: • Monica B. Chibita, Dean, Faculty of Journalism, Media and Communication, Uganda Christian University, • Margaret B. Sentamu, Executive Director, Uganda Media Women’s Association, an umbrella Media Association for female journalists who own and operate 101.7 Mama FM. • Dr. Peter G. Mwesige, Executive Director, African Centre for Media Excellence • John Okande, National Programme Officer- Communication and Information Sector and the UNESCO Regional Office for Eastern Africa All photos are the property of Internews except where otherwise noted. -

AMUDAT District

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA KARAMOJA AMUDAT District HAzArd, risk And VulnerAbility Profile August 2014 AMUDAT HAZARD, RISK AND VULNERABILITY PROFILE | i With support from: United Nations Development Programme Plot 11, Yusuf Lule Road P.O. Box 7184 Kampala, Uganda For more information: www.undp.org ii | AMUDAT HAZARD, RISK AND VULNERABILITY PROFILE Contents Acronyms ................................................................................................................... iv Acknowledgement .......................................................................................................1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................2 INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................................3 Objectives ...................................................................................................................3 Methodology ................................................................................................................3 Overview of the District ...............................................................................................6 Location ...................................................................................................................6 Administration ..........................................................................................................6 District profile ...........................................................................................................6 -

Economic Contributions of Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining in Uganda: Gold and Clay

Economic Contributions of Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining in Uganda: Gold and Clay January 2018 This document is an output from a project funded by the UK Department for International Development (DFID) through the Research for Evidence Division (RED) for the benefit of developing countries. However, the views expressed and information contained in it is not necessarily those of, or endorsed by DFID, which can accept no responsibility for such views or information or for any reliance placed on them. Contacts: Pact Global UK Ravenswood, Baileys Lane Westcombe, Somerset BA4 6EN UK +44 (0) 7584651984 [email protected] [email protected] Alliance for Responsible Mining Calle 32 B SUR # 44 A 61 Envigado – Colombia +57 (4) 332 47 11 [email protected] [email protected] Authorship: This report was prepared by Dr Maria Laura Barreto (team leader, legal aspects), Patrick Schein (economic aspects), Dr Jennifer Hinton (technical and social aspects), and Dr Felix Hruschka (context, mapping and compilation) as part of the EARF project ‘Understanding the Economic Contribution of Small-scale Mining in East Africa’ covering Kenya, Rwanda, and Uganda. The authors wish to acknowledge the important research assistance of Elizabeth Echavarria and Marina Ruete from ARM. Special thanks are extended to the project’s Expert Advisors Majala Mlagui (Kenya), Stephen Turyahikayo (Uganda), and Augustin Bida (Rwanda); Pact staff Jacqueline Ndirangu and Ildephonse Niyonsaba; Project Co-Managers Cristina Villegas of Pact and Géraud Brunel of ARM; the DFID EARF leadership who funded this study; and the in-country DFID representatives of Uganda, Kenya, and Rwanda, with whom the researchers met while conducting in-country assessments. -

(Fgm) in Uganda Key Findings

FEMALE GENITAL MUTILATION (FGM) IN UGANDA KEY FINDINGS 1• Support for abandonment is widespread •6 Potential intergenerational effects: Mutilated but persistent social norms hamper women are less supportive of abandonment discontinuation: 95% of women in eastern than uncut women and more likely to support Uganda support abandonment of FGM but their sons’ marriage only with mutilated girls. strong social influences and peer pressure limit Mothers also play a key role in influencing women’s ability to abandon the practice and their daughters’ decision to undergo FGM. This influence others against it. may result in some form of intergenerational perpetuation of FGM whereby mutilated 2• Male circumcision as a driver of FGM: women act as promoters for the continuation Women’s desire to participate at male of the practice among younger generations. circumcision ceremonies and celebrations – a key community social event that only mutilated women are allowed to attend – remains an important driver of FGM, especially among older married women. 3• Age at cutting: Nowadays, girls tend to be mutilated at a younger age than in the past. Age at cutting appears to be lower among Pokot communities in Karamoja (around 14–15 years) than among the Sabiny in Sebei (17–19 years). Among Pokot women, FGM is still being carried out mostly on adolescent girls as a rite of passage before marriage. Among the Sabiny, FGM is increasingly performed among older uncut married women. 4• Changes in the practice Nowadays, girls undergo the (illegal) practice in secret, often in remote locations and unsafe conditions. Cross-border FGM is also becoming increasingly common given perceived weaker anti-FGM law enforcement on the border with Kenya. -

Final Report New Roads for Resilience Reconnaissance

NEW ROADS FOR RESILIENCE Reconnaissance report from Uganda Authors: Hilary Galiwango Enock Kajubi September 2016 “New Roads for Resilience: Connecting Roads, Water and Livelihoods” Table of Contents LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................................................. 2 LIST OF FIGURES ................................................................................................................................................................ 2 LIST OF ABRREVIATIONS ................................................................................................................................................ 3 1 Introduction and objectives ................................................................................................................................ 4 1.1 Project Background ........................................................................................................................................ 4 2 Identifying pilot roads ........................................................................................................................................... 5 2.1 General ............................................................................................................................................................... 5 2.2 Methodology .................................................................................................................................................... 5 2.2.1 Preparing district -

Karamoja, Uganda Enhanced Market Analysis 2016

FEWS NET Uganda Enhanced Market Analysis 2016 KARAMOJA, UGANDA ENHANCED MARKET ANALYSIS 2016 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Chemonics International Inc. for the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET), contract number AID-OAA-I-12-00006. The authors’ views Famineexpressed Early in Warningthis publication Systems do Network not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency i for International Development or the United States government. FEWS NET Uganda Enhanced Market Analysis 2016 About FEWS NET Created in response to the 1984 famines in East and West Africa, the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) provides early warning and integrated, forward-looking analysis of the many factors that contribute to food insecurity. FEWS NET aims to inform decision makers and contribute to their emergency response planning; support partners in conducting early warning analysis and forecasting; and, provide technical assistance to partner-led initiatives. To learn more about the FEWS NET project, please visit http://www.fews.net Acknowledgments FEWS NET gratefully acknowledges the network of partners in Uganda who contributed time, analysis, and data to make this report possible. See the list of participants and their organizations in Annexes 1 and 3. Famine Early Warning Systems Network ii FEWS NET Uganda Enhanced Market Analysis 2016 Table of Contents Preface ............................................................................................................................................................................................................