Understanding VIA's Role in History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Make Downtown Travel Downright Fun!

FROM DOWNTOWN YOU CAN ALSO RIDE VIA BUS ROUTES TO OTHER GREAT ATTRACTIONS. Route 7 – to Brackenridge Park Japanese Tea Garden San Antonio Botanical Garden *San Antonio Museum of Art *San Antonio Zoo *Witte Museum WELCOME ABOARD! It’s fun. Downtown San Antonio has so much to offer, and there is no better way to see the sights than on VIA’s downtown transit service. And for those who want to venture beyond downtown, there is a good chance VIA can get you there, too. It’s convenient. Our service runs from early morning until late evening, Make and our circulator routes come by every 10 minutes — at stops located throughout downtown. Downtown It’s fast. Go from Alamo Plaza to just about anywhere in downtown San Antonio within 10 minutes. VIA Primo Route 100 – to Travel South Texas Medical Center and It’s thrifty. University of Texas at San Antonio 1604 Just $1.20 a ride ($2.50 for Express), with discounts Downright for seniors, children, the mobility impaired and Route 5 – to Medicare recipients with VIA Reduced Fare ID. Pay San Antonio International Airport Fun! by cash or ride all you want with a VIA Day Pass or monthly Big Pass. Route 64 – to Sea World of Texas Riders using Primo 100 to circulate within the down- town area may request a special free transfer from Route 94 – to the operator upon arrival at the Westside Multimodal Six Flags Fiesta Texas Transit Center. This transfer can only be used for boarding the next Primo going towards Ellis Alley Pick up individual route schedules at the downtown VIA Information Center, on the bus, or online at viainfo.net. -

City Response to DART Downtown Transit Study

Oak Cliff Gateway Community Meeting TIGER Streetcar Project Update Bicycle and Pedestrian Projects TIGER Streetcar Project Initial Dallas streetcar planning efforts grew out of CBD Comprehensive Transportation Plan and D2 light rail analysis Focused within downtown loop NCTCOG received a grant on behalf of the City of Dallas from the Federal Transit Administration for the streetcar starter line to serve the CBD and North Oak Cliff workforce The 1.6 mile base project runs from Union Station to Methodist Hospital at a cost of approximately $48.6M including vehicles $26M in federal funding $12.8M in local funding (Regional Toll-road Revenue) $9M from DART for vehicles 2 TIGER Streetcar Project 3 TIGER Streetcar Project Stacey and Witbeck/Carcon were given notice to proceed with final design and construction in September 2012 and bridge demolition is currently underway Base project has been enhanced to provide double track operation along Zang and Colorado Completion of base project is scheduled for October 2014 Brookville Equipment Corporation was given notice to proceed with production of two vehicles in March 2013 First American made off-wire modern streetcar vehicle The Dallas streetcar will be 8’ wide, 66.5’ long with capacity to carry 41 passenger seated and maximum 170 standees Anticipated vehicle delivery is late summer 2014 4 TIGER Streetcar Project Extension The Regional Transportation Council (RTC) recently reprogrammed $30.87M in Texas Mobility Funds to the Dallas Streetcar Project The funds are proposed to extend the base project an additional 1.25 miles and provide two additional vehicles .75 miles south from Methodist Hospital to the Bishop Arts District ($15M) .5 miles north to the Dallas Convention Center/Omni Hotel ($7.87M) Streetcar Vehicles ($8M) 5 TIGER Streetcar Project Extension 6 TIGER Streetcar Project Extension Operation and Maintenance Cost Operation for base Streetcar Project funded by Dallas Area Rapid Transit Base project assumes weekday service only 5:00 a.m. -

Fy 2018 Business Plan

Dallas Area Rapid Transit FY 2018 BUSINESS PLAN Including FY 2018 Annual Budget and Twenty-Year Financial Plan FY 2018 Business Plan L4.indd 1 7/31/17 9:40 AM DART BOARD MEMBERS Sue Bauman Dallas Catherine Cuellar Dallas and Cockrell Hill Mark C. Enoch Garland, Rowlett and Glenn Heights Tim A. Hayden Carrollton and Irving Ray Jackson Dallas Jonathan R. Kelly Garland Patrick Kennedy Dallas Jon-Bertrell Killen Dallas Michele Wong Krause Dallas Amanda Moreno Dallas Gary Slagel Richardson, University Park, Addison and Highland Park Rick Stopfer Irving Dominique Torres Dallas Paul N. Wageman Plano Faye Moses Wilkins Plano and Farmers Branch FY 2018 Business Plan L4.indd 2 7/31/17 9:40 AM FY 2018 Business Plan (09/26/17) How to Use This Book What’s in this Book This book contains the Business Plan for Fiscal Year 2018 (FY 2018 – which ends September 30, 2018) for Dallas Area Rapid Transit (DART or the Agency). The Business Plan provides the DART Board of Directors, customers, taxpayers, elected officials, and other stakeholder groups of our region with a comprehensive summary of the Agency's plans and commitments to improve regional mobility, enhance the quality of life, and stimulate economic development. This document consolidates the key elements of the FY 2018 Annual Budget, the FY 2018 Twenty-Year Financial Plan, the Transit System Plan, and the Agency's Strategic Plan. A summary of the information contained in the various sections follows. The formal Letter of Transmittal summarizes priorities and issues for the upcoming year. The section titled Who We Are should help those not familiar with DART to understand the basis from which the Agency operates. -

Living in Dallas, Texas Demographics Dallas Is the Third-Largest City in Texas and the Ninth-Largest in the United States

Living in Dallas, Texas Demographics Dallas is the third-largest city in Texas and the ninth-largest in the United States. Dallas forms the heart of the large metropolitan area in north central Texas, commonly referred to as the “metroplex”. The metroplex, a 12-county area encompassing more than 120 cities, is anchored by the City of Dallas in the east and the City of Fort Worth in the west. The population of Dallas is around 1.3 million according to the US Census Bureau. This ultra- modern and sophisticated city is the largest economic center of the 12-county Dallas-Fort Worth metropolitan area, which is the fourth-largest metropolitan area in the United States. The Dallas community is world-class with a diverse population located on a total land area of 384 square miles. Dallas is centrally located within the US and serves as a commercial and cultural hub of the Southwest region. Within a four-hour flight from most North American destinations, the travel possibilities are endless. Dallas is also a leading business and meeting city. Dallas-Fort Worth is home to 24 Fortune 500 companies and has become a hotspot in recent years for corporate relocations. Notable Fortune 500 companies include: Exxon Mobil, AT&T, Energy Transfer Equity, American Airlines Group, Southwest Airlines, Texas Instruments, GameStop, D.R. Horton, and Dr. Pepper Snapple Group. Entertainment/Culture With many entertainment districts within a short distance of downtown, Dallas is a unique melting pot which mixes local history with arts, culture, dining, and more. Dallas is stylish and cosmopolitan, a city with a well-earned reputation for fashion, shopping, and prosperity. -

Free to Ride!

FREE TO RIDE! NO SUNDAY SERVICE UPTOWN PEARL ST OLIVE & E McKINNEY 722 OLIVE ST 21 K WOODALL D-LINK RODGERS FWY PEARL/ARTS B 20 D 21 FLORA ST DISTRICT STATION CEDAR RD SPRINGS 19 MAP NOT TO SCALE DALLAS ARTS 20 Pearl/Arts District DISTRICT 18 17 LEGEND 19 East Transfer D-Link Route & Stop Center MCKINNEY AVE Dallas Streetcar & Stop FIELD ST Victory DART Light Rail and Station FEDERAL ST. BROOM ST PEARL ST M-Line Trolley West Transfer St.HARWOOD Paul Trinity Railway Express Center CESAR CHAVEZ BLVD MAIN & Commuter Rail and Station ST. PAUL ST Akard ST. PAUL C 12 LAMAR ST 11 15 13 ELM ST 14 WEST END MAIN ST HISTORIC MAIN STREET YOUNG ST DISTRICTRECORD DISTRICT 16 West End LAMAR ST G ROSS AVE FIELD ST TRINITY RIVER DALLAS FARMERS G ST 10 MARKET ST MARKET DISTRICT PACIFIC AVE ELM ST 4 BC HOUSTON & HOUSTON ST MAIN ST 3 MARILLA ELM 9 2 COMMERCE ST 5 1 CONVENTION CENTER E A WOOD ST B STATION 8 Union Convention Center Station 6 YOUNG ST LAMAR ST 7 Cedars 2 MIN-WALK REUNION DALLAS STREETCAR 5 MIN-WALK DISTRICT TO BISHOP ARTS DISTRICT Route 722 Serves All Local Bus Stops POWHATTAN STBELLEVIEW ST Stop Numbers and Places of Interest 620 NO SUNDAY SERVICE 1. Convention Center Station 8. Dealey Plaza 15. Main Street Garden No Holiday Service on days observed for Memorial Day, 2. Kay Bailey Hutchison 9. Sixth Floor Museum at 16. Dallas Farmers Market July 4, Labor Day, Thanksgiving DALLAS TRINITY RIVER HOUSTON ST Convention Center Dealey Plaza Day, Christmas Day and New Year’s Day. -

Stakeholder Involvement Summary With

Prepared for Volume 2: Developing Vision 2040 Prepared by Phase 3 Stakeholder Involvement Summary with November 2016 Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................ 1 1.0 Introduction ............................................................................................................... 1 2.0 Community Outreach .................................................................................................. 3 2.1 Targeted Outreach and Community Events ............................................................ 3 2.2 Social Media, News Media, and Paid Advertising ..................................................... 5 2.3 Print and Digital Survey Outreach ........................................................................ 7 2.4 Vision 2040 Open Houses ................................................................................... 7 3.0 Survey Summary ...................................................................................................... 11 3.1 Survey Questions and Responses ........................................................................ 11 3.2 General Comments ........................................................................................... 21 3.3 Respondent Characteristics ................................................................................ 22 4.0 Project Prioritization Workshops .............................................................................. 27 4.1 VTAC Workshop -

REFERENCE BOOK March 2019

DALLAS AREA RAPID TRANSIT REFERENCE BOOK March 2019 Version 10.0 WHAT The Dallas Area Rapid Transit (DART) Reference Book is a convenient and easy to use compilation of information on the DART system. It provides staff with key data, maps and contacts. The objective is to allow staff to respond to inquiries, with consistent, accurate information in a timely manner. WHO The DART Reference Book was compiled by the Capital Planning Division of the Growth/Regional Development Department. Numerous DART departments provide input and assist Capital Planning with annual updates. WHEN DART Capital Planning coordinates an update after each fiscal year ending September 30. Because some financial information does not become immediately available, the Reference Book update is completed by the second quarter (March) of the following fiscal year. AVAILABILITY A limited number of printed copies are made for senior management. A PDF version of the Reference Book is available for DART staff on DART InfoStation, and also on www.DART.org under About DART. VERSION CONTROL VERSION NUMBER VERSION DATE DESCRIPTION OF CHANGES 1 8.2010 DRAFT 2 3.2011 FY10 Actual/FY11 Budget Update 3 4.2012 FY11 Actual/FY12 Budget Update 4 4.2013 FY12 Actual/FY13 Budget Update 5 3.2014 FY13 Actual/FY14 Budget Update New Board Member committee 5.1 5.2014 assignments/minor edits 6 3.2015 FY14 Actual/FY15 Budget Update Corrected LRT on-time performance for 6.1 7.2015 PDF version only. 7 3.2016 FY15 Actual/FY16 Budget Update 8 3.2017 FY16 Actual/FY17 Budget Update 9 3.2018 FY17 Actual/FY18 Budget Update 10 3.2019 FY18 Actual/FY19 Budget Update II DART REFERENCE BOOK – MARCH 2019 DART POINTS-OF-CONTACT ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICES DART MAILING/PHYSICAL ADDRESS 214-749-3278 DALLAS AREA RAPID TRANSIT P.O. -

Community Streetcar Coalition News Clips

April 19 – April 26, 2018 COMMUNITY STREETCAR COALITION NEWS CLIPS COMPILED BY BROADCAST CLIPS Dallas CBS11 April 24, 2018 LINK: https://bit.ly/2JotrqF Riding the streetcar in Dallas could soon cost riders a small fee. It currently runs from Union Station to the Bishop Arts District, and DART is suggesting a $1 fare starting in September. City council will consider the matter tomorrow. El Paso KVIA April 20, 2018 LINK: https://bit.ly/2Fkxx0y In El Paso the Camino Real Regional Mobility Authority is adding the region’s first two-way bike lane, part of the ongoing El Paso streetcar project. As the project is closer to becoming finalized, drivers are learning to adjust to the change in traffic, and so are bicyclists. ABC7’s Josie Ortegon has more. We’re having to come back at this point and look at the infrastructure on our roads and say how can we make them safer? Scott White has been keeping a close eye on the El Paso streetcar project. As part of the addition of streetcars, the Camino Real Regional Mobility Authority is adding new two-way bike lanes, a designated green crossing lane for bicyclists, bicycle signals and four-foot-high delineators. It looks like protection, but if a car goes out of control, if you fall and hit this thing. Martin Bartlett with the El Paso streetcar project says engineers chose the delineators specifically because the height allows for maximum reflectivity from a vehicle’s headlights. White is also worried about the amount of space within the bike lanes. -

Dlinkdowntowndallas29jan18.Pdf

FREE TO RIDE! DART AROUND DOWNTOWN DART RAIL MAP ROUTH DART AROUNROSSD AVE DOWNTOWN DDTC MedPark to Denton FREE TO RIDE! PEARL ST HV/LL M-LINE TO GASTON ELM PEARL & A OLIVE ST UPTOWN SAN JACINTO CEDAR DOWNTOWN D-LINK SPRINGS RD Old Town Deep Ellum MAIN ST DART AROUNRDoute DO W722NTOWN DALLAS ARTS Hebron DALLAS RODGERS FWYDISTRICT DEEP N. CARROLLTON/ PARKER ROAD DART AROUND DOWNTOWN A 19 FRANKFORD 17 ELLUM Terminal Downtown Effective January 29, 2018 WOODALL Plano COMMERCEGOOD LATIMER A DFW AIRPORT MCKINNEY 18 & ELM ST B CityLine/Bush Trinity Mills Downtown GOOD LATIMER ROWLETT Victory KLYDE WARREN PARK Galatyn Park ST East Transfer Belt Line Downtown Center Downtown Arapaho BROOM ST CESAR CHAVEZ BLVD Carrollton Garland FEDERALSt. Paul CANTON HARWOOD ST Only Peak Weekday ORANGE LINE Spring Valley PEARL ST North Lake ST. PAUL MAIN ST College Forest/Jupiter ROSS JACINTOAVE ST Akard Farmers LBJ/Central West Transfer FIELD Branch SAN GRIFFIN Irving Center Forest Lane LBJ/Skillman ST 14 Convention 15 Center ST 13 FARMERS C MARKET Royal Lane Walnut Hill West End LAMAR ST Lake CANTON ST Las Colinas Highlands RECORD STWEST END MAIN STREET 16 Urban Center Park Lane AKARD ST DISTRICT Walnut Hill/ HOUSTON DALLAS FARMERS 12 Denton Lovers Lane White Rock MARKET DISTRICT 11 FIELD ST Univ. Dallas MAIN & MARILLA ST ST PACIFIC AVE ST. PAUL D MAIN 10 Hop on for FREE. Bachman Hop on for FREE. Mockingbird E & LAMAR MARKET STCOMMERCE ST ELM ST MAIN ST WOOD ST Kay Bailey Hutchison Cityplace/Uptown 9 4 Convention Center Burbank 2 CONVENTION CENTER 3 MAP NOT TO SCALE Deep Ellum F 1 Inwood/ Pearl/Arts STATION Love Field District Hop off for FUN. -

Dallas Streetcar Mapa

PEARL ST OLIVE ST WOODALL RODGERS FWY MAP NOT TO SCALE CEDAR RD SPRINGS FLORA Pearl/Arts District East Transfer Center MCKINNEY AVE FIELD BROOM FEDERAL ST. ELM ST PEARL ST St. Paul CHAVEZ CESAR HARWOOD ST Akard ST. PAUL ST AKARD ST LAMAR ST 620_Streetcar_July27-2020.indd 2 FIELD ST OPERATION • HOURS: 7 days a week, 5:30 a.m. - midnight West Transfer RECORD ST Center WOOD ST 400-013-0520 400-013-0520 • FREQUENCY: 20 minutes G ROSS AVE West End LAMAR ST GRIFFIN ST G YOUNG ST • TRIP LENGTH: 2.45 miles PACIFIC AVE MARILLA ST • COST: $1 One – Way Fare ELM ST Included with any valid DART pass MARKET ST C MAIN ST One-Way pass available in DART’s GoPass® app Tap and go with a reloadable GoPass® Tap card HOUSTON STCOMMERCE ST (PU: No cash accepted onboard vehicleB WOOD ST Convention Center Visit DART.org/DallasStreetcar for more information LAMAR ST 374-005-1120 FROM 12-28-2019) YOUNG ST RULES: DART’s Code of Conduct 3 MIN-WALK Cedars FUNCIONAMIENTO EBJ • HORARIO: 7 días a la semana, de 5:30 a.m. Union Station hasta la medianoche. POWHATTAN ST • FRECUENCIA: Cada 20 minutos BELLEVIEW ST • DURACION DE VIAJE: 2.45 millas DALLAS • TARIFA: $1 por tarifa de ida o vuelta STREETCAR Incluido con cualquier pase válido de DART TRINITY RIVER Pase de ida o vuelta disponible en la aplicación GoPass® de DART STREETCAR SCHEDULE INSIDE UPDATED: JULY 27, 2020 L5 DESIGNER; AJ AE: AREYES JULY STREETCAR SCHEDULE INSIDE UPDATED: HOUSTON VIADUCT UNION STATION STOP Toca y viaja con una tarjeta recargable GoPass® Tap A Board DART Rail, TRE and No se acepta efectivo a bordo del vehículo Amtrak at EBJ Union Station Visite DART.org/DallasStreetcar para más (Corner of Houston & Young) información REGLAS: Código de Conducta de DART. -

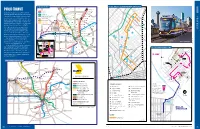

Public Transit

to Denton (operated by DCTA) DFW RAIL SYSTEM M-LINE TROLLEY - UPTOWN AND DOWNTOWN DALLAS ACCESS PLANO LEMMON AVE BLACKBURN ST PUBLIC TRANSIT PARKER ROAD RED LINE President George Bush Turnpike Downtown Plano OAK LAWN AVE | Dallas Area Rapid Transit (DART), which BLUE LINE NORTH CARROLLTON/FRANKFORD CityLine/Bush President Ge org e GREEN LINE CARROLLTON Bu includes light rail and bus service, features RICHARDSON Galatyn Park s h T ADDISON u r n CARLISLE ST TRINITY RAILWAY EXPRESS p Trinity Mills PUBLIC TRANSIT i the nation’s longest light-rail network and Arapaho Center k (No Sunday service on TRE) e CITYPLACE BLVD ORANGE LINE Weekday Peak Only 1 Downtown Carrollton Tollway Dallas North enables easy access to key job centers in TEXRAIL LINE FARMERS BRANCH Spring Valley ROWLETT GARLAND LEMMON AVE E Dallas and its suburbs. DART also provides DCTA A-TRAIN Farmers Branch LBJ/Central Downtown DOWNTOWN LEMMON AVE W convenient light-rail access to Dallas Fort ORANGE LINE Forest Lane Garland GRAPEVINE XX Royal Lane ROWLETT Worth International Airport and interfaces ORANGE LINE Belt Irving (Peak hours on weekdays only) Line Convention Walnut Hill/Denton Walnut Hill Forest/Jupiter 2 DFW LBJ/Skillman HALL ST with the Texas Railway Express (TRE). Center Las Colinas FARE ZONE BOUNDARY Airport Bachman Park Lane Lake Highlands Urban UNIVERSITY The TRE is an intercity commuter train COLE AVE PARKINGNORTH AVAILABLE Terminal A North Lake Center PARK Lovers White Rock 3 Burbank RICHLAND College HIGHLAND Lane that transports passengers between HILLS LOVE DALLAS DFW University FIELD PARK XX IRVING of Dallas Inwood/ 4 downtown Dallas and Fort Worth, with Love Field Mockingbird West MESQUITE KATY TRAIL stops at several “mid-cities” suburbs in FORT WORTH Bell Irving Southwestern 5 Richland Hills Medical District/ Cityplace/Uptown between. -

The Transfer Fall 2016 Rev2.Cdr

Oregon Electric Railway Historical Society Volume 21 503 Issue 3 Fall 2016 Reminder to members: Please be sure your dues In this issue: are up to date. 2016 dues were due Jan 1, 2016. Bring Home Locomotive #21 - John Nagy, Don Evans.................1 Oregon Railway Historical Society News...................................2 If it has been longer than one year since you renewed, Powerland Operations - Kenneth Peters.................................2 go to our website: oerhs.org and download an Thanks to Recent Donors ........................................................4 application by clicking: Become a Member Museum Director’s Report - Greg Bonn...............................5 MAX Light Rail Destination Sign Conversion - Steve Morgan ....6 Restoration & Maintenance WST - Dave Rowe..........................8 See this issue in color on line OERHS Annual Meeting & Banquet..........................................8 at oerhs.org/transfer Dallas, Transit Mecca of Texas, Part 3 - Mark Kavanagh..............9 OERHS Wish List and Project Donations - John Nagy.............12 Bring it Home to Oregon – The Oregon Electric Locomotive #21 Project By John Nagy, Don Evans and the Board The Bring the 21 Home to Oregon project provides a the next 34 years it could be found moving freight from very rare opportunity to be able to repatriate a tangible Portland south to Eugene and west to Forest Grove. piece of Oregon history to a place that was its actual operating home over 100 years ago. And to finally have a In 1946, all four of these locomotives were sold to the piece of Oregon Electric Railway equipment at the Oregon British Columbia Electric Railway (BCER). Oregon Electric Railway Museum. Electric #21 became BCER #961 for another 34 year career of service until 1980.