Ethics in Exile: a Comparative Study of Shinran and Maimonides

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Goethe, the Japanese National Identity Through Cultural Exchange, 1889 to 1989

Jahrbuch für Internationale Germanistik pen Jahrgang LI – Heft 1 | Peter Lang, Bern | S. 57–100 Goethe, the Japanese National Identity through Cultural Exchange, 1889 to 1989 By Stefan Keppler-Tasaki and Seiko Tasaki, Tokyo Dedicated to A . Charles Muller on the occasion of his retirement from the University of Tokyo This is a study of the alleged “singular reception career”1 that Goethe experi- enced in Japan from 1889 to 1989, i. e., from the first translation of theMi gnon song to the last issues of the Neo Faust manga series . In its path, we will high- light six areas of discourse which concern the most prominent historical figures resp. figurations involved here: (1) the distinct academic schools of thought aligned with the topic “Goethe in Japan” since Kimura Kinji 木村謹治, (2) the tentative Japanification of Goethe by Thomas Mann and Gottfried Benn, (3) the recognition of the (un-)German classical writer in the circle of the Japanese national author Mori Ōgai 森鴎外, as well as Goethe’s rich resonances in (4) Japanese suicide ideals since the early days of Wertherism (Ueruteru-zumu ウェル テルヅム), (5) the Zen Buddhist theories of Nishida Kitarō 西田幾多郎 and D . T . Suzuki 鈴木大拙, and lastly (6) works of popular culture by Kurosawa Akira 黒澤明 and Tezuka Osamu 手塚治虫 . Critical appraisal of these source materials supports the thesis that the polite violence and interesting deceits of the discursive history of “Goethe, the Japanese” can mostly be traced back, other than to a form of speech in German-Japanese cultural diplomacy, to internal questions of Japanese national identity . -

“Silence Is Your Praise” Maimonides' Approach To

Rabbi Rafael Salber “Silence is your praise” Maimonides’ Approach to Knowing God: An Introduction to Negative Theology Rabbi Rafael Salber The prophet Isaiah tells us, For my thoughts are not your thoughts, neither are my ways your ways, saith the Lord. For as the heavens are higher than the earth, so are my ways higher than your ways. 73 The content of this verse suggests the inability of mankind to comprehend the knowledge and thoughts of God, as well as the 73 Isaiah 55: 8- 9. The context of the verse is that Isaiah is conveying the message to the people of Israel that the ability to return to God (Teshuvah) is available to them, since the “traits” of God are conducive to this. See Moreh Nevuchim ( The Guide to the Perplexed ) 3:20 and the Sefer haIkkarim Maamar 2, Ch. 3. 65 “Silence is your praise”: Maimonides’ Approach to Knowing God: An Introduction to Negative Theology divergence of “the ways” of God and the ways of man. The extent of this dissimilarity is clarified in the second statement, i.e. that it is not merely a distance in relation, but rather it is as if they are of a different category altogether, like the difference that exists between heaven and earth 74 . What then is the relationship between mankind and God? What does the prophet mean when he describes God as having thoughts and ways; how is it even possible to describe God as having thoughts and ways? These perplexing implications are further compounded when one is introduced to the Magnum Opus of Maimonides 75 , the Mishneh Torah . -

Download the Full Edition

Meorot A Forum of Modern Orthodox Discourse (formerly Edah Journal) Marheshvan 5768 CONTENTS Editor’s Introduction to the Marheshvan 5768 Edition Eugene Korn ARTICLES Farteitcht un Farbessert (On “Correcting” Maimonides) Menachem Kellner Ethics and Warfare Revisited Gerald J. Blidstein Michael J. Broyde Women's Eligibility to Write Sifrei Torah Jen Taylor Friedman Dov Linzer Authority and Validity: Why Tanakh Requires Interpretation, and What Makes an Interpretation Legitimate? Moshe Sokolow REVIEW ESSAY Maimonides Contra Kabbalah: A Review of Maimonides’ Confrontation with Mysticism by Menachem Kellner James A. Diamond Meorot 6:2 Marheshvan 5768 A Publication of Yeshivat Chovevei Torah Rabbini cal School © 2007 STATEMENT OF PURPOSE t Meorot: A Forum of Modern Orthodox Discourse (formerly The Edah Journal) Statement of Purpose Meorot is a forum for discussion of Orthodox Judaism’s engagement with modernity, o published by Yeshivat Chovevei Torah Rabbinical School. It is the conviction of Meorot that this discourse is vital to nurturing the spiritual and religious experiences of Modern Orthodox Jews. Committed to the norms of halakhah and Torah, Meorot is dedicated to free inquiry and will be ever mindful that “Truth is the seal of the Holy One, Blessed be He.” r Editors Eugene Korn, Editor Nathaniel Helfgot, Associate Editor Joel Linsider, Text Editor o Editorial Board Dov Linzer (YCT Rabbinical School), Chair Michael Berger Moshe Halbertal (Israel) e Naftali Harcsztark Norma Baumel Joseph Simcha Krauss Barry Levy Adam Mintz Tamar Ross (Israel) A Forum of Modern Orthodox Discourse M Meorot will publish two online editions per year, and will be available periodically in hard- copy editions. -

REL 444/544 Medieval Japanese Buddhism, Fall 2019 CRN16061/2 Mark Unno

REL 444/544 Medieval Japanese Buddhism, Fall 2019 CRN16061/2 Mark Unno Instructor: Mark T. Unno, Office: SCH 334 TEL 6-4973, munno (at) uoregon.edu http://pages.uoregon.edu/munno/ Wed. 2:00 p.m. - 4:50 p.m., Condon 330; Office Hours: Mon 10:00-10:45 a.m.; Tues 1:00-1:45 p.m. No Canvas site. Overview REL 444/544 Medieval Japanese Buddhism focuses on selected strains of Japanese Buddhism during the medieval period, especially the Kamakura (1185-1333), but also traces influences on later developments including the modern period. The course weaves together the examination of religious thought and cultural developments in historical context. We begin with an overview of key Buddhist concepts for those without prior exposure and go onto examine the formative matrix of early Japanese religion. Once some of the outlines of the intellectual and cultural framework of medieval Japanese Buddhism have been brought into relief, we will proceed to examine in depth examples of significant medieval developments. In particular, we will delve into the work of three contemporary figures: Eihei Dōgen (1200-1253), Zen master and founding figure of the Sōtō sect; Myōe of the Shingon and Kegon sects, focusing on his Shingon practices; and Shinran, founding figure of Jōdo Shinshū, the largest Pure Land sect, more simply known as Shin Buddhism. We conclude with the study of some modern examples that nonetheless are grounded in classical and medieval sources, thus revealing the ongoing influence and transformations of medieval Japanese Buddhism. Themes of the course include: Buddhism as state religion; the relation between institutional practices and individual religious cultivation; ritual practices and transgression; gender roles and relations; relations between ordained and lay; religious authority and enlightenment; and two-fold truth and religious practice. -

Against the Heteronomy of Halakhah: Hermann Cohen's Implicit Rejection of Kant's Critique of Judaism

Against the Heteronomy of Halakhah: Hermann Cohen’s Implicit Rejection of Kant’s Critique of Judaism George Y. Kohler* “Moses did not make religion a part of virtue, but he saw and ordained the virtues to be part of religion…” Josephus, Against Apion 2.17 Hermann Cohen (1842–1918) was arguably the only Jewish philosopher of modernity whose standing within the general philosophical developments of the West equals his enormous impact on Jewish thought. Cohen founded the influential Marburg school of Neo-Kantianism, the leading trend in German Kathederphilosophie in the second half of the nineteenth and the first decade of the twentieth century. Marburg Neo-Kantianism cultivated an overtly ethical, that is, anti-Marxist, and anti-materialist socialism that for Cohen increasingly concurred with his philosophical reading of messianic Judaism. Cohen’s Jewish philosophical theology, elaborated during the last decades of his life, culminated in his famous Religion of Reason out of the Sources of Judaism, published posthumously in 1919.1 Here, Cohen translated his neo-Kantian philosophical position back into classical Jewish terms that he had extracted from Judaism with the help of the progressive line of thought running from * Bar-Ilan University, Department of Jewish Thought. 1 Hermann Cohen, Religion der Vernunft aus den Quellen des Judentums, first edition, Leipzig: Fock, 1919. I refer to the second edition, Frankfurt: Kaufmann, 1929. English translation by Simon Kaplan, Religion of Reason out of the Sources of Judaism (New York: Ungar, 1972). Henceforth this book will be referred to as RR, with reference to the English translation by Kaplan given after the German in square brackets. -

Shinjin, Faith, and Entrusting Heart: Notes on the Presentation of Shin Buddhism in English

Shinjin, Faith, and Entrusting Heart: Notes on the Presentation of Shin Buddhism in English Daniel G. Friedrich 浄土真宗の「信心」をいかに英語で伝えるか? ―ローマ字表記と英語訳をめぐる論考― フリードリック・ダニエル・G Abstract In 1978 with the publication of the Letters of Shinran: A translation of the Mattōshō, translators working at the Hongwanji International Center sparked a debate that continues at present regarding the translation or transliteration of the term shinjin. That this debate continues into the present day is not surprising when we consider that shinjin is the cornerstone of Shin Buddhist paths of awakening. This paper begins by analyzing shinjin within Shinran’s writings and the Shin Buddhist tradition. Second, it examines arguments for and against either the transliteration or translation of shinjin. This paper then concludes by arguing that depending on context it is necessary to employ both strategies in order to properly communicate Shin Buddhism in English. Key words : shinjin, faith, entrusting heart, translation, transliteration, Jōdo Shin-shū (Received September 30, 2008) 抄 録 1978 年に『末灯鈔』(親鸞の書簡)の英訳を出版するにあたり、本願寺国際センター翻 訳部では、「信心」という用語を英語に翻訳するか、そのままローマ字表記にするかにつ いて論争が起こった。この問題に関する議論は現在も継続中である。「信心」が浄土真宗 の要の概念であることを考えれば、議論が今も続いていること自体は驚くにはあたらない。 本論は、まず親鸞の著書と真宗教学における「信心」の意味を分析し、次に「信心」を英 語の用語で言い換える立場とローマ字表記にする立場の両者の主張を検証する。結論では、 英語圏の人々に浄土真宗を伝えるためには、文脈に応じて二通りの方法を使い分けること が必要だと述べる。 キーワード:信心、翻訳、ローマ字表記、浄土真宗 (2008 年 9 月 30 日受理) - 107 - 大阪女学院大学紀要5号(2008) Introduction In 1978 with the publication of the Letters of Shinran: A translation of the Mattōshō1, the Hongwanji International -

H E a R T B E

HEARTBEAT heartbeatAmerican Committee for Shaare Zedek Medical Center in Jerusalem 49 West 45th Street • New York, NY 10036 212-354-8801 • www.acsz.org I SRAEL IS COUNTING ON US...TO CARE AND TO CURE SPRING 2011 KESTENBAUM FAMILY MAKES LEADERSHIP GIFT TO DEDICATE ECHOCARDIOGRAPHY MACHINE IN THE PEDIATRIC CARDIOLOGY DEPARTMENT Alan and Deborah Kestenbaum have been involved with Shaare HEARTBEAT Zedek for more than two decades. Deborah’s father, Hal Beretz, served as the chair of the Hospital’s International Board of Highlights Governors, her mother Anita is a member of the National Women’s Division and Deborah currently serves as the Chair of the Development Board of the Women’s Division. PAGE 8 In recent years, Deborah, who has always metals with Glencore and Philipp Brothers in Profiles in Giving been involved in countless charitable endeavors, New York. Dr. Jack and Mildred Mishkin her local synagogue and her children’s schools, Recently, the Kestenbaums decided to Dr. Monique and Mordecai Katz has taken on a more prominent leadership take their leadership to the next level by mak- role in the Shaare Zedek Women’s Division. ing a magnanimous gift to purchase a new PAGE 4-7 A graduate of Queens College with a BA in Echocardiography machine for the Pediatric Economics, Deborah explains, “Shaare Zedek Cardiology Department. Highlights from the Hospital has always been a part of my family and I am looking forward to increasing my involvement While advanced cardiac care is not typ- Hospital Opens New Cosmetic with this incredible Hospital.” ically associated with younger patients, the Care Center and New Digestive reality is that a large number of children do Diseases Institute Alan, holds a BA in Economics from indeed face serious cardiac problems. -

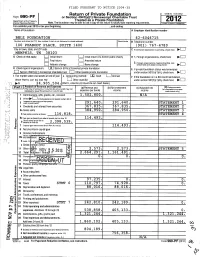

Return of Private Foundation Form 990-PF

' FILED PURSUANT TO NOTICE 2004-35 Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust ^O Department of the Treasury Treated as a Private Foundation Internal Revenue Service Note. The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements. For calendar year 2012 or tax year beginning , and ending Name of foundation A Employer identification number BELZ FOUNDATION 62-6046715 Number and street (or P O box number if mail is not delivered to street address ) Room/suite B Telephone number 100 PEABODY PLACE, SUITE 1400 (901) 767-4780 City or town, state, and ZIP code C If exemption application is pending , check here ► MEMPHIS, TN 38103 G Check all that apply: L_J Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations , check here Final return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, Add ress chan ge Name c hange check here and attach computation ► H Check type of organization . LXJ Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated = Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust = Other taxable private foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here Fair market value X I of all assets at end of year J Accounting method: Cash L_J Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination (from Part 11, col (c), line 16) = Other (specify) under section 507(b)(1)(B), check here ► s 2 4 , 9 0 5 , 5 0 4 . -

The Purple Robe Incident and the Formation of the Early Modern Sōtō Zen Institution

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 36/1: 27–43 © 2009 Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture Duncan Williams The Purple Robe Incident and the Formation of the Early Modern Sōtō Zen Institution The transition from the medieval to the early modern Buddhist order was directed in large measure by a new regulatory regime instituted by the Toku- gawa bakufu. These new directives issued from Edo increasingly regulated every aspect of both political and religious life during the first half of the seventeenth century. As the bakufu extended its control over domains through a pyramidal hierarchy of order towards the center, similar formations of regulation govern- ing Buddhist sectarian order emerged in an increasingly formalized fashion. At the same time, power did not operate in a unilateral direction as Buddhist insti- tutions attempted to shape regulation, move toward a self-regulatory model of governance, and otherwise evade control by the center through local interpre- tations and implementations of law. This essay takes up how state regulation of religion was managed by Sōtō Zen Buddhism, with particular attention given to rules governing the clerical ranks and the robes worn by clerics of high rank. The 1627 “purple robe incident” is examined as an emblematic case of the new power relationship between the new bakufu’s concern about subversive elements that could challenge its hold on power; the imperial household’s cus- tomary authority to award the highest-ranking, imperially-sanctioned “purple robe”; and Buddhist institutions that laid claim on the authority to recognize spiritual advancement. keywords: Sōtō Zen Buddhism—Tokugawa bakufu and religion—hatto—“purple robe incident” Duncan Williams is Associate Professor of Japanese Buddhism and Chair of the Center for Japanese Studies at UC Berkeley. -

Pure Mind, Pure Land a Brief Study of Modern Chinese Pure Land Thought and Movements

Pure Mind, Pure Land A Brief Study of Modern Chinese Pure Land Thought and Movements Wei, Tao Master of Arts Faculty ofReligious Studies McGill University Montreal, Quebec, Canada July 26, 2007 In Partial Fulfillment ofthe Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Faculty ofReligious Studies of Mc Gill University ©Tao Wei Copyright 2007 All rights reserved. Library and Bibliothèque et 1+1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Bran ch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-51412-2 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-51412-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, électronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Reconsidering the Theoretical/Practical Divide: the Philosophy of Nishida Kitarō

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Reconsidering The Theoretical/Practical Divide: The Philosophy Of Nishida Kitarō Lockland Vance Tyler University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Tyler, Lockland Vance, "Reconsidering The Theoretical/Practical Divide: The Philosophy Of Nishida Kitarō" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 752. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/752 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RECONSIDERING THE THEORETICAL/PRACTICAL DIVIDE: THE PHILOSOPHY OF NISHIDA KITARŌ A Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Philosophy University of Mississippi by LOCKLAND V. TYLER APRIL 2013 Copyright Lockland V. Tyler 2013 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Over the years professional philosophy has undergone a number of significant changes. One of these changes corresponds to an increased emphasis on objectivity among philosophers. In light of new discoveries in logic and science, contemporary analytic philosophy seeks to establish the most objective methods and answers possible to advance philosophical progress in an unambiguous way. By doing so, we are able to more precisely analyze concepts, but the increased emphasis on precision has also been accompanied by some negative consequences. These consequences, unfortunately, are much larger and problematic than many may even realize. What we have eventually arrived in at in contemporary Anglo-American analytic philosophy is a complete repression of humanistic concerns. -

Marranism As Judaism As Universalism: Reconsidering Spinoza

religions Article Marranism as Judaism as Universalism: Reconsidering Spinoza Daniel H. Weiss Faculty of Divinity, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB3 9BS, UK; [email protected] Received: 7 December 2018; Accepted: 3 March 2019; Published: 7 March 2019 Abstract: This essay seeks to reconsider the relation of the universal-rational ethos of Spinoza’s thought to the Jewish tradition and culture in which he was raised and socially situated. In particular, I seek to engage with two previous portrayals—specifically, those of Isaac Deutscher and Yirmiyahu Yovel—that present Spinoza’s universalism as arising from his break from or transcendence of Judaism, where the latter is cast primarily (along with Christianity) as a historical-particular and therefore non-universal tradition. In seeking a potential source of Spinoza’s orientation, Yovel points Marrano culture, as a sub-group that was already alienated from both mainstream Judaism and mainstream Christianity. By contrast, I argue that there are key elements of pre-Spinoza Jewish-rabbinic conceptuality and material culture that already enact a profoundly universalist ethos, specifically in contrast to more parochialist or particularist ethical dynamics prevalent in the culture of Christendom at the time. We will see, furthermore, that the Marrano dynamics that Yovel fruitfully highlights in fact have much in common with dynamics that were already in place in non-Marrano Jewish tradition and culture. As such, we will see that Spinoza’s thought can be understood not only as manifesting a Marrano-like dynamic in the context of rational-philosophical discourse, but also as preserving a not dissimilar Jewish-rabbinic dynamic at the same time.