“Silence Is Your Praise” Maimonides' Approach To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analytic Philosophy and the Fall and Rise of the Kant–Hegel Tradition

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-87272-0 - Analytic Philosophy and the Return of Hegelian Thought Paul Redding Excerpt More information INTRODUCTION: ANALYTIC PHILOSOPHY AND THE FALL AND RISE OF THE KANT–HEGEL TRADITION Should it come as a surprise when a technical work in the philosophy of language by a prominent analytic philosopher is described as ‘an attempt to usher analytic philosophy from its Kantian to its Hegelian stage’, as has 1 Robert Brandom’s Making It Explicit? It can if one has in mind a certain picture of the relation of analytic philosophy to ‘German idealism’. This particular picture has been called analytic philosophy’s ‘creation myth’, and it was effectively established by Bertrand Russell in his various accounts of 2 the birth of the ‘new philosophy’ around the turn of the twentieth century. It was towards the end of 1898 that Moore and I rebelled against both Kant and Hegel. Moore led the way, but I followed closely in his foot- steps. I think that the first published account of the new philosophy was 1 As does Richard Rorty in his ‘Introduction’ to Wilfrid Sellars, Empiricism and the Philosophy of Mind, with introduction by Richard Rorty and study guide by Robert Brandom (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1997), pp. 8–9. 2 The phrase is from Steve Gerrard, ‘Desire and Desirability: Bradley, Russell, and Moore Versus Mill’ in W. W. Tait (ed.), Early Analytic Philosophy: Frege, Russell, Wittgenstein (Chicago: Open Court, 1997): ‘The core of the myth (which has its origins in Russell’s memories) is that with philosophical argument aided by the new logic, Russell and Moore slew the dragon of British Idealism ...An additional aspect is that the war was mainly fought over two related doctrines of British Idealism ...The first doctrine is an extreme form of holism: abstraction is always falsification. -

Bertrand Russell in the Great Soviet Encyclopedia

Russell's philosophical evolution led him into a broad program of research where he applied the resources of mathematical logic to theoreti cal inquiry. In the neorealist and neopositivist stages of Russell's evolution this program led to the formulating of his Theory of Knowledge, and from then on he again recognized the independent significance of philosophical problems. 3 Russell created the concept of logical atomism and he founded logical analysis. Bertrand Russell in the The working out of philosophical questions in mathematics occupies a large place in his works. One of the paradoxes in set theory (Russell's Great Soviet Encyclopedia: Paradox) led him to the formation of the original version of axiomatic set theory4 (see also Theory of Types) and to the consequent attempt at l a translation from Russian reducing mathematics to logic. Russell and Whitehead coauthored the 3 vol ume work "Principia Mathematica" (1910-1913). They systematized and developed the deductive-axiomatic formation of logic (see Logicism). USSELL2 Bertrand (18.5.1872, Trelleck, Wales--2.2.1970, Penrhyndeu Russell developed the original Theory of Descriptions. R draeth, Wales), English philosopher, logician, mathematician, sociolo In his sociological views Russell was close to Psychologism. Accord gist, public figure. Between 1910 and 1916 Russell was a professor at ing to him, at the foundations of the historical process and the behaviour Cambridge University, where he graduated in 1894. He was professor at of people lie instincts, passions. Russell said that from a combination various universities in Great Britain and the U.S. In 1908 he became a of factors determining historical change it is impossible to pick out the member of the Royal Society. -

Noahidism Or B'nai Noah—Sons of Noah—Refers To, Arguably, a Family

Noahidism or B’nai Noah—sons of Noah—refers to, arguably, a family of watered–down versions of Orthodox Judaism. A majority of Orthodox Jews, and most members of the broad spectrum of Jewish movements overall, do not proselytize or, borrowing Christian terminology, “evangelize” or “witness.” In the U.S., an even larger number of Jews, as with this writer’s own family of orientation or origin, never affiliated with any Jewish movement. Noahidism may have given some groups of Orthodox Jews a method, arguably an excuse, to bypass the custom of nonconversion. Those Orthodox Jews are, in any event, simply breaking with convention, not with a scriptural ordinance. Although Noahidism is based ,MP3], Tạləmūḏ]תַּלְמּוד ,upon the Talmud (Hebrew “instruction”), not the Bible, the text itself does not explicitly call for a Noahidism per se. Numerous commandments supposedly mandated for the sons of Noah or heathen are considered within the context of a rabbinical conversation. Two only partially overlapping enumerations of seven “precepts” are provided. Furthermore, additional precepts, not incorporated into either list, are mentioned. The frequently referenced “seven laws of the sons of Noah” are, therefore, misleading and, indeed, arithmetically incorrect. By my count, precisely a dozen are specified. Although I, honestly, fail to understand why individuals would self–identify with a faith which labels them as “heathen,” that is their business, not mine. The translations will follow a series of quotations pertinent to this monotheistic and ,MP3], tạləmūḏiy]תַּלְמּודִ י ,talmudic (Hebrew “instructive”) new religious movement (NRM). Indeed, the first passage quoted below was excerpted from the translated source text for Noahidism: Our Rabbis taught: [Any man that curseth his God, shall bear his sin. -

Brsq 0096.Pdf

/,,-,,,.I (hrir"M/W:|J,„'JJ(// Bulk Mail -:::-``.::`:.1:.t` U.S. Postage ci{08O#altruntr%%ditl.i PAID Permit No. 5659 CfldemmJin, ORE 23307 Alexandria, VA MR. DENNIS J. DARLAND /9999 .1965 WINDING HILLS RD. (1304) DAVENPORT IA 52807 T=..:€,,5fa=.`¥ _ atiTst:.:..¥5 3`=3 13LT„j§jLj;,:j2F,f:Lu,i,:,„„„„3.,§§.i;§„L„;j„§{j;;`„„:i THE BHRTRAND RUSSELL SOCIHTY QUARTERLY Newsletter o the Bertrand Russell Socie November 1997 No. 96 FROM THH EDITOR John Shosky ................................... 3 FROM THE PRESIDHNT John R. Lenz ................................... 4 BERTRAND RUSSELL SOCIETY CONFERENCH: 19-21 JUNE 1998 ...................... RUSSELL NEWS: Publications, etc ....................... 6 RUSSELL'S PLATO David Rodier ................................... 7 A BOOK REVIEW John Shosky .................................. 19 MEMORY COMES AND GOES: A Video Review Cliff Henke ................................... 22 THE GREATER ROCHESTER RUSSELL SET Peter Stone ................................... 24 BERTRAND RUSSELL SOCIETY Membership PI.orlles ............................ 25 BERTRAND RUSSELL SOCIETY 1998 Call for Board Nominations .................. 27 BERTRAND RUSSELL SOCIETY Membership pror]]e Form . 29 1 FROM THE EDITOR BHRTRAND RUSSELL SOCIETY John Shosky 1998 Membership Renewal Form ................... 31 American University Wc beSn this issue with a report from the society president, John Lenz. He will announce the preliminary details of the Annual Bertrand Russell Society Corferencc, which will be held June 19-21 at the Ethics Center of the University of South Florida in St. Petersburg. John's report will be followed by "Russell News", which is a column of short blurbs about Russell, works on Russell, society happenings, reports on members, general gossip, and other vital talking points for the informed and discerning society member. In my view, the standard of information one should strive for, in a Platonic sense, is Ken Blackwell, the guru of Russell trivia, realizing that Ken has a considerable head start on all of us. -

Following the Argument Where It Leads

Following The Argument Where It Leads Thomas Kelly Princeton University [email protected] Abstract: Throughout the history of western philosophy, the Socratic injunction to ‘follow the argument where it leads’ has exerted a powerful attraction. But what is it, exactly, to follow the argument where it leads? I explore this intellectual ideal and offer a modest proposal as to how we should understand it. On my proposal, following the argument where it leaves involves a kind of modalized reasonableness. I then consider the relationship between the ideal and common sense or 'Moorean' responses to revisionary philosophical theorizing. 1. Introduction Bertrand Russell devoted the thirteenth chapter of his History of Western Philosophy to the thought of St. Thomas Aquinas. He concluded his discussion with a rather unflattering assessment: There is little of the true philosophic spirit in Aquinas. He does not, like the Platonic Socrates, set out to follow wherever the argument may lead. He is not engaged in an inquiry, the result of which it is impossible to know in advance. Before he begins to philosophize, he already knows the truth; it is declared in the Catholic faith. If he can find apparently rational arguments for some parts of the faith, so much the better: If he cannot, he need only fall back on revelation. The finding of arguments for a conclusion given in advance is not philosophy, but special pleading. I cannot, therefore, feel that he deserves to be put on a level with the best philosophers either of Greece or of modern times (1945: 463). The extent to which this is a fair assessment of Aquinas is controversial.1 My purpose in what follows, however, is not to defend Aquinas; nor is it to substantiate the charges that Russell brings against him. -

The Theory of Descriptions 1. Bertrand Russell (1872-1970): Mathematician, Logician, and Philosopher

Louis deRosset { Spring 2019 Russell: The Theory of Descriptions 1. Bertrand Russell (1872-1970): mathematician, logician, and philosopher. He's one of the founders of analytic philosophy. \On Denoting" is a founding document of analytic philosophy. It is a paradigm of philosophical analysis. An analysis of a concept/phenomenon c: a recipe for eliminating c-vocabulary from our theories which still captures all of the facts the c-vocabulary targets. FOR EXAMPLE: \The Name View Analysis of Identity." 2. Russell's target: Denoting Phrases By a \denoting phrase" I mean a phrase such as any one of the following: a man, some man, any man, every man, all men, the present King of England, the present King of France, the centre of mass of the Solar System at the first instant of the twentieth century, the revolution of the earth round the sun, the revolution of the sun round the earth. (479) Includes: • universals: \all F 's" (\each"/\every") • existentials: \some F " (\at least one") • indefinite descriptions: \an F " • definite descriptions: \the F " Later additions: • negative existentials: \no F 's" (480) • Genitives: \my F " (\your"/\their"/\Joe's"/etc.) (484) • Empty Proper Names: \Apollo", \Hamlet", etc. (491) Russell proposes to analyze denoting phrases. 3. Why Analyze Denoting Phrases? Russell's Project: The distinction between acquaintance and knowledge about is the distinction between the things we have presentation of, and the things we only reach by means of denoting phrases. [. ] In perception we have acquaintance with the objects of perception, and in thought we have acquaintance with objects of a more abstract logical character; but we do not necessarily have acquaintance with the objects denoted by phrases composed of words with whose meanings we are ac- quainted. -

H E a R T B E

HEARTBEAT heartbeatAmerican Committee for Shaare Zedek Medical Center in Jerusalem 49 West 45th Street • New York, NY 10036 212-354-8801 • www.acsz.org I SRAEL IS COUNTING ON US...TO CARE AND TO CURE SPRING 2011 KESTENBAUM FAMILY MAKES LEADERSHIP GIFT TO DEDICATE ECHOCARDIOGRAPHY MACHINE IN THE PEDIATRIC CARDIOLOGY DEPARTMENT Alan and Deborah Kestenbaum have been involved with Shaare HEARTBEAT Zedek for more than two decades. Deborah’s father, Hal Beretz, served as the chair of the Hospital’s International Board of Highlights Governors, her mother Anita is a member of the National Women’s Division and Deborah currently serves as the Chair of the Development Board of the Women’s Division. PAGE 8 In recent years, Deborah, who has always metals with Glencore and Philipp Brothers in Profiles in Giving been involved in countless charitable endeavors, New York. Dr. Jack and Mildred Mishkin her local synagogue and her children’s schools, Recently, the Kestenbaums decided to Dr. Monique and Mordecai Katz has taken on a more prominent leadership take their leadership to the next level by mak- role in the Shaare Zedek Women’s Division. ing a magnanimous gift to purchase a new PAGE 4-7 A graduate of Queens College with a BA in Echocardiography machine for the Pediatric Economics, Deborah explains, “Shaare Zedek Cardiology Department. Highlights from the Hospital has always been a part of my family and I am looking forward to increasing my involvement While advanced cardiac care is not typ- Hospital Opens New Cosmetic with this incredible Hospital.” ically associated with younger patients, the Care Center and New Digestive reality is that a large number of children do Diseases Institute Alan, holds a BA in Economics from indeed face serious cardiac problems. -

Adult Education 2017

Adult Education 2017 Texts ● Culture ● Language ● Faith In troduction Dear Members and Friends, The ACT Jewish Community is proud to present 2017’s Adult Education program. In 2016 we had the opportunity to learn from a variety of amazing scholars, including visiting professors, authors, journalists, and culminating with our Scholar in Residence, Eryn London. This year, we have the opportunity to present a fantastic program that explores the full spectrum of Jewish life and learning. Throughout this document, you will find general information and explanations of each course on offer along with a timetable of all of our programs. Each course will be marked with one or more of the following four symbols; - Torah Scroll – This implies that there is a textual element to this course - Chamtza – This implies there is a cultural element to the course - Aleph – These courses will primarily be language based - Ten Commandments – These courses will include Jewish Laws and Customs and will focus on the religious aspect of Judaism As always, our programs are designed to broadly encompass different ideas, observances, and denominations. Last year we had a record number of attendees, this year we would like to aim for 100% participation. Please do join us, Rabbi Alon Meltzer Week at a Glance Sunday - Shabbat Cooking – 5 Sessions over the course of the year Monday - Jewish Journeys – Weekly (Semester 1) - Midrash for Beginners – Weekly (Semester 2) Tuesday - Paint Night (with wine) – 5 Sessions over the course of the year Wednesday - Café Ivrit – Weekly Thursday - Jewish Philosophy – Weekly (Semester 1) - Poems and Poets – Weekly (Semester 2) Shabbat Cooking Join Rabbi Meltzer for a practical cooking class that will explore different concepts and themes relating to Shabbat laws of the kitchen. -

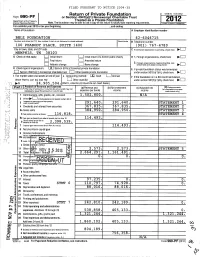

Return of Private Foundation Form 990-PF

' FILED PURSUANT TO NOTICE 2004-35 Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust ^O Department of the Treasury Treated as a Private Foundation Internal Revenue Service Note. The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements. For calendar year 2012 or tax year beginning , and ending Name of foundation A Employer identification number BELZ FOUNDATION 62-6046715 Number and street (or P O box number if mail is not delivered to street address ) Room/suite B Telephone number 100 PEABODY PLACE, SUITE 1400 (901) 767-4780 City or town, state, and ZIP code C If exemption application is pending , check here ► MEMPHIS, TN 38103 G Check all that apply: L_J Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations , check here Final return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, Add ress chan ge Name c hange check here and attach computation ► H Check type of organization . LXJ Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated = Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust = Other taxable private foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here Fair market value X I of all assets at end of year J Accounting method: Cash L_J Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination (from Part 11, col (c), line 16) = Other (specify) under section 507(b)(1)(B), check here ► s 2 4 , 9 0 5 , 5 0 4 . -

Canadian Friends of Boys Town Jerusalem

Shana Tova Happy New Year Canadian Friends of Boys Town Jerusalem Boys Town Jerusalem is a unique ‘community of youth’ where boys from every economic, social and cultural Mylwvry rivn tyrq background acquire an inspiring technical, Torah and academic education which is so vital to Israel. September 2012 | Volume 11 | No. 2 Boys Town Jerusalem Impresses the Pros First and Only High School in Israel on Oracle System As the 2011-2012 school year give them enough. The results: their began last September, Boys Town average grade on the bagrut (national Jerusalem students were once again matriculation) exam was 85%, and making history. The results and six students scored 100%!”, Saruk the rewards have been remarkable. reported. Boys Town Jerusalem was the first AND ONLY high school Open Source systems are based on in Israel to offer a curriculum in the groundbreaking “Solaris” system “Open Source Computer Operating created by Sun Microsystems, now a Systems” (the Oracle Corporation’s part of Oracle Corporation. In 2011, “OpenSolaris”). Last week, five Boys Town Jerusalem was selected of our seventeen pioneer students by Israel’s Ministry of Education to were invited to present their senior pioneer the Solaris curriculum. This projects to the Israel-based Oracle follows a Boys Town milestone in Users Group Forum, a gathering of 2000 when we were the first high the top echelon of Israel’s computer school designated as the center of professionals. instruction for the CISCO Networking Management Program. Today, Boys Town is the country’s only high school licensed to prepare students in The students’ presentation left much of the audience visibly stunned. -

Impact Report

IMPACT REPORT Powering the Agencies that Make Community Possible 20 17 1 Give On behalf of everyone your gift touched this year from across the globe to across Jewishly town—THANK YOU! It matters. 2 4 CONTENTS LETTER FROM CEO & BOARD CHAIR 5 6 7 MISSION FEDERATION CAMPAIGN FOR DIRECTORY JEWISH NEEDS 8 12 13 NEW WOMEN’S YOUNG INITIATIVES PHILANTHROPY LEADERS 14 16 ALLOCATIONS BY THE & GRANTS NUMBERS 17 COUNCIL OF JEWISH ORGANIZATIONS 3 2017 was an invigorating and inspiring year for our community. Shaping the lives of young adults, supporting This past year saw a change in the way those in crisis around the world, strengthening that Jewish Nevada works with and in the the Jewish identities of youth, and ensuring that community. The goal of these new aspects Holocaust survivors in Nevada continue to live is to fundamentally transform our state-wide independently and with dignity—the work of community, not just this year, but generationally. Jewish Nevada, Nevada’s Jewish Federation and Jewish Nevada is enhancing more lives than our partners transcends age, gender, geography, ever before, with the introduction of initiatives and levels of religious observance. At our core, like One Happy Camper, Right Start, Onward we are committed to building community and Israel, and LIFE & LEGACYTM, and we are taking raising the funds needed to support the critical successful programs to new heights. Whether programs and services relied upon by thousands these pages are your frst introduction to our in Nevada, in Israel, and in more than 70 work or you have been a dedicated supporter countries around the world. -

1 a Tale of Two Interpretations

Notes 1 A Tale of Two Interpretations 1. As Georges Dicker puts it, “Hume’s influence on contemporary epistemology and metaphysics is second to none ... ” (1998, ix). Note, too, that Hume’s impact extends beyond philosophy. For consider the following passage from Einstein’s letter to Moritz Schlick: Your representations that the theory of rel. [relativity] suggests itself in positivism, yet without requiring it, are also very right. In this also you saw correctly that this line of thought had a great influence on my efforts, and more specifically, E. Mach, and even more so Hume, whose Treatise of Human Nature I had studied avidly and with admiration shortly before discovering the theory of relativity. It is very possible that without these philosophical studies I would not have arrived at the solution (Einstein 1998, 161). 2. For a brief overview of Hume’s connection to naturalized epistemology, see Morris (2008, 472–3). 3. For the sake of convenience, I sometimes refer to the “traditional reading of Hume as a sceptic” as, e.g., “the sceptical reading of Hume” or simply “the sceptical reading”. Moreover, I often refer to those who read Hume as a sceptic as, e.g., “the sceptical interpreters of Hume” or “the sceptical inter- preters”. By the same token, I sometimes refer to those who read Hume as a naturalist as, e.g., “the naturalist interpreters of Hume” or simply “the natu- ralist interpreters”. And the reading that the naturalist interpreters support I refer to as, e.g., “the naturalist reading” or “the naturalist interpretation”. 4. This is not to say, though, that dissenting voices were entirely absent.