Draft Safe Harbor Agreement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aspects of House Finch Breeding Biology in Hawaii

ASPECTS OF HOUSE FINCH BREEDING BIOLOGY IN HAWAII CHARLES VAN RIPER III Bent (1968) summarized information avail- Puu Laau, is the last remaining major mamane-naio able on the breeding biology of the House forest in Hawaii. Finch ( Curpodacus mexicanus). Although The stippled areas of figure 1 represent a broad spectrum of the forest types on the island of Hawaii; this species has been studied quite extensively included are native, introduced, and mixed stands of in its North American home range, little atten- vegetation. Areas 2, 3, and 5 are dry forest regions tion has been paid to it in Hawaii. Grinnell with annual rainfall of 76 cm or less; Puu Laau (2) (1911) reported on different color patterns of has mean annual rainfall of 50 cm, Puu Waawaa (3) 64 cm, and Puu Lehua (5) has 76 cm. The Kohala the House Finch in Hawaii, and Richardson Mountain complex ( 1) has a mean annual rainfall of and Bowles (1964) mentioned that on 23 June 229 cm, Puu 00 (4) has 483 cm, and the Kulani- 1960 they found a nestling that had fallen from Mauna Loa complex (6) has 317 cm. its nest on Kauai. On Mauna Kea, Berger Birds were mist-netted, color-banded, and released (1972) found House Finch nests with eggs from 1971 through 1973. Nest and tree heights were taken with a clinometer when it was impractical to as early as 6 April (1968) and as late as 17 use a tape measure. Nests and eggs were measured July (1967). Eleven nests were built on hori- with calipers and weighed on a sensitive spring bal- zontal branches of mamane (Sophora chryso- ance. -

Downloadable Data Collection

Smetzer et al. Movement Ecology (2021) 9:36 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40462-021-00275-5 RESEARCH Open Access Individual and seasonal variation in the movement behavior of two tropical nectarivorous birds Jennifer R. Smetzer1* , Kristina L. Paxton1 and Eben H. Paxton2 Abstract Background: Movement of animals directly affects individual fitness, yet fine spatial and temporal resolution movement behavior has been studied in relatively few small species, particularly in the tropics. Nectarivorous Hawaiian honeycreepers are believed to be highly mobile throughout the year, but their fine-scale movement patterns remain unknown. The movement behavior of these crucial pollinators has important implications for forest ecology, and for mortality from avian malaria (Plasmodium relictum), an introduced disease that does not occur in high-elevation forests where Hawaiian honeycreepers primarily breed. Methods: We used an automated radio telemetry network to track the movement of two Hawaiian honeycreeper species, the ʻapapane (Himatione sanguinea) and ʻiʻiwi (Drepanis coccinea). We collected high temporal and spatial resolution data across the annual cycle. We identified movement strategies using a multivariate analysis of movement metrics and assessed seasonal changes in movement behavior. Results: Both species exhibited multiple movement strategies including sedentary, central place foraging, commuting, and nomadism , and these movement strategies occurred simultaneously across the population. We observed a high degree of intraspecific variability at the individual and population level. The timing of the movement strategies corresponded well with regional bloom patterns of ‘ōhi‘a(Metrosideros polymorpha) the primary nectar source for the focal species. Birds made long-distance flights, including multi-day forays outside the tracking array, but exhibited a high degree of fidelity to a core use area, even in the non-breeding period. -

Keauhou Bird Conservation Center

KEAUHOU BIRD CONSERVATION CENTER Discovery Forest Restoration Project PO Box 2037 Kamuela, HI 96743 Tel +1 808 776 9900 Fax +1 808 776 9901 Responsible Forester: Nicholas Koch [email protected] +1 808 319 2372 (direct) Table of Contents 1. CLIENT AND PROPERTY INFORMATION .................................................................... 4 1.1. Client ................................................................................................................................................ 4 1.2. Consultant ....................................................................................................................................... 4 2. Executive Summary .................................................................................................. 5 3. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 6 3.1. Site description ............................................................................................................................... 6 3.1.1. Parcel and location .................................................................................................................. 6 3.1.2. Site History ................................................................................................................................ 6 3.2. Plant ecosystems ............................................................................................................................ 6 3.2.1. Hydrology ................................................................................................................................ -

Twenty-Three of 69 Since Discovery of 17 SOME LIMITING

17 SOME LIMITING FACTORS AND RESEARCH NEEDS OF ENDANGERED HAWAIIAN FOREST BIRDS Winston E. Banko U. S. Fish & Wildlife Service Hawaii Volcanoes National Park Hawaii 96718 It is well known that Hawaiian birds are particularly sus ceptible to depopulation and extinction. Twenty-three of 69 endemic species or races have disappeared since discovery of Hawai'i by Europeans 200 years ago. Except for Warner (1968) and Atkinson (1977), only super ficial inquiries have been made into historical aspects and underlying factors of the Hawaiian forest bird decline. After several years of field and laboratory investigation, Warner explained th~ rlisappearance of forest birds as being caused primarily by disease. Atkinson advanced a theory based on historical evidence that arboreal predation by rats was a leading factor. The object of my long-term historical investigation is to document and compare the salient facts on the geography and chro nology of Hawaiian bird loss, species by species; to chronicle what is known about all factors of depopulation~-predation, disease, habitat alteration, and food competition; and to draw such conclusions as seem warranted. At the First Conference in Natural Sciences two years ago, Banko and Banko (1976) reported on the potential significance of food depletion in the decline of Hawaiian forest birds. The role played by the Big-headed ant (Pheidole megacephala) in destroying much of the endemic insect fauna at elevations generally less than 3000 feet (914 m) before 1890 was sketched at that time. (The term "insect" will be used hereafter as including other arthropods as well). I now wish to elaborate on the possible impact of foreign parasitic flies and .wasps in depleting native insect foods impor tant to the small Hawaiian forest birds at higher elevation~. -

Non-Native Trees Provide Habitat for Native Hawaiian Forest Birds

NON-NATIVE TREES PROVIDE HABITAT FOR NATIVE HAWAIIAN FOREST BIRDS By Peter J. Motyka A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science In Biology Northern Arizona University December 2016 Approved: Jeffrey T. Foster, Ph.D., Co-chair Tad C. Theimer, Ph. D., Co-chair Carol L. Chambers, Ph. D. ABSTRACT NON-NATIVE TREES PROVIDE HABITAT FOR NATIVE HAWAIIAN FOREST BIRDS PETER J. MOTYKA On the Hawaiian island of Maui, native forest birds occupy an area dominated by non- native plants that offers refuge from climate-limited diseases that threaten the birds’ persistence. This study documented the status of the bird populations and their ecology in this novel habitat. Using point-transect distance sampling, I surveyed for birds over five periods in 2013-2014 at 123 stations across the 20 km² Kula Forest Reserve (KFR). I documented abundance and densities for four native bird species: Maui ‘alauahio (Paroreomyza montana), ʻiʻiwi (Drepanis coccinea), ʻapapane (Himatione sanguinea), and Hawaiʻi ʻamakihi, (Chlorodrepanis virens), and three introduced bird species: Japanese white-eye (Zosterops japonicas), red-billed leiothrix (Leiothrix lutea), and house finch (Haemorhous mexicanus). I found that 1) native forest birds were as abundant as non-natives, 2) densities of native forest birds in the KFR were similar to those found in native forests, 3) native forest birds showed varying dependence on the structure of the habitats, with ʻiʻiwi and ‘alauahio densities 20 and 30 times greater in forest than in scrub, 4) Maui ‘alauahio foraged most often in non-native cape wattle, eucalyptus, and tropical ash, and nested most often in non-native Monterey cypress, Monterey pine, and eucalyptus. -

Apapane (Himatione Sanguinea)

The Birds of North America, No. 296, 1997 STEVEN G. FANCY AND C. JOHN RALPH 'Apapane Himatione sanguinea he 'Apapane is the most abundant species of Hawaiian honeycreeper and is perhaps best known for its wide- ranging flights in search of localized blooms of ō'hi'a (Metrosideros polymorpha) flowers, its primary food source. 'Apapane are common in mesic and wet forests above 1,000 m elevation on the islands of Hawai'i, Maui, and Kaua'i; locally common at higher elevations on O'ahu; and rare or absent on Lāna'i and Moloka'i. density may exceed 3,000 birds/km2 The 'Apapane and the 'I'iwi (Vestiaria at times of 'ōhi'a flowering, among coccinea) are the only two species of Hawaiian the highest for a noncolonial honeycreeper in which the same subspecies species. Birds in breeding condition occurs on more than one island, although may be found in any month of the historically this is also true of the now very rare year, but peak breeding occurs 'Ō'ū (Psittirostra psittacea). The highest densities February through June. Pairs of 'Apapane are found in forests dominated by remain together during the breeding 'ōhi'a and above the distribution of mosquitoes, season and defend a small area which transmit avian malaria and avian pox to around the nest, but most 'Apapane native birds. The widespread movements of the 'Apapane in response to the seasonal and patchy distribution of ' ōhi'a The flowering have important implications for disease Birds of transmission, since the North 'Apapane is a primary carrier of avian malaria and America avian pox in Hawai'i. -

8 Commercial Forestry Harvesting of Planted Koa

Acacia koa in Hawai‘i: Facing the Future Proceedings of the 2016 Symposium, Hilo, HI: www.TropHTIRC.org, www.ctahr.hawaii.edu/forestry COMMERCIAL FORESTRY HARVESTING OF PLANTED KOA: A CASE STUDY FROM HALEAKALA RANCH Steve McMinn (Pacific Rim Tonewoods) Paniolo Tonewoods is a joint venture between Taylor Guitars and Pacific Rim Tonewoods, and was formed in 2015 specifically to supply koa guitar components to Taylor and other instrument companies. It is our desire to promote, encourage and invest in koa forestry, and it is our intention to build a small, efficient milling operation in Hawai‘i in the coming years. Haleakala Ranch, (“HR”), on Maui, has two stands of Koa that were planted in 1985, in conjunction with “A Million Trees of Aloha”, a program started by Jean Ariyoshi, then Governor Ariysohi’s wife. The two stands, A and B, are of about 20 acres and 8 acres, (8 and 3 hectares), and are at 5000 feet and 6000 feet of elevation respectively (1500 and 1800 m) (figure 1 and 2). Figure 1: Stand A from below. 8 Acacia koa in Hawai‘i: Facing the Future Proceedings of the 2016 Symposium, Hilo, HI: www.TropHTIRC.org, www.ctahr.hawaii.edu/forestry Figure 2: Plaque commemorating the planting of the Haleakala Ranch stands. Both stands are said to have been planted from seedlings grown from Hawai‘i Island seed stock. In both stands, the canopies were closed, and both had a floor that was covered chiefly with leaf litter, although A had some gorse intrusion. B is long and narrow; the trees are more widely spaced. -

Acacia Koa Fabaceae

Acacia koa Gray Fabaceae - Mimosoideae koa LOCAL NAMES English (koa acacia,koa,Hawaiian mahogany); Hawaian (koa); Trade name (koa) BOTANIC DESCRIPTION Acacia koa is a large, evergreen tree to 25 m tall, stem diameter to 150 cm at breast height. Trees occurring in dense, wet native forest stands typically retain a straight, narrow form. In the open, trees develop more spreading, branching crowns and shorter, broader trunks. A. koa has one main tap root and an otherwise shallow, spreading root system. Bark gray, Exclosure at Pohakuokala Gulch, Maui, rough, scaly and thick. Hawaii (Forest and Kim Starr) A. koa belongs to the thorn-less, phyllodinous group of the Acacia subgenus Heterophyllum. Young seedlings have bipinnate compound true leaves with 12-15 pairs of leaflets. Where forest light is sufficient, seedlings stop producing true leaves while they are less than 2 m tall. True leaves are retained longer by trees growing in dense shade. Phyllodes are sickle-shaped and often more than 2.5 cm wide in the middle and blunt pointed on each end. Inflorescence is a pale yellow ball, 8.5 mm in diameter, 1-3 on a common stalk. Each inflorescence is composed of many bisexual flowers. Each Habit at Makawao forest reserve, Maui, flower has an indefinite number of stamens and a single elongated style. Hawaii (Forest and Kim Starr) Pods are slow to dehisce, 15 cm long and 2.5-4 cm wide. They contain 6- 12 seeds that vary from dark brown to black. The generic name ‘acacia’ comes from the Greek word ‘akis’, meaning point or barb. -

Hawaiian Plant Studies 14 1

The History, Present Distribution, and Abundance of Sandalwood on Oahu, Hawaiian Islands: . Hawaiian Plant Studies 14 1 HAROLD ST. JOHN 2 INTRODUCTION album L., the species first commercialized, TODAY IT IS a common belief of the resi is now considered to have been introduced dents of the Hawaiian Islands that the san into India many centuries ago and cultivated dalwood tree was exterminated during the there for its economic and sentimental val sandalwood trade in the early part of the ues. Only in more recent times has it at . nineteenth century and that it is now ex tained wide distribution and great abun tinct on the islands. To correct this impres dance in that country. It is certainly indige sion, the following notes are presented.. nous in Timor and apparently so all along There is a popular as well as a scientific the southern chain of the East Indies to east interest in the sandalwood tree or iliahi of ern Java, including the islands of Roti, We the Hawaiians, the fragrant wood of which tar, Sawoe, Soemba, Bali, and Madoera. The was the first important article of commerce earliest voyagers found it on those islands exported from the Hawaiian Islands. and it was early an article of export, reach For centuries the sandalwood, with its ing the markets of China and India (Skotts pleasantly fragrant dried heartwood, was berg, 1930: 436; Fischer, 1938). The in much sought for. In the Orient, particularly sufficient and diminishing supply of white in China, Burma, and India, the wood was sandalwood gave it a very high and increas used for the making of idols and sacred ing value.' Hence, trade in the wood was utensils for shrines, choice boxes and carv profitable even when a long haul was in ings, fuel for funeral pyres, and joss sticks volved. -

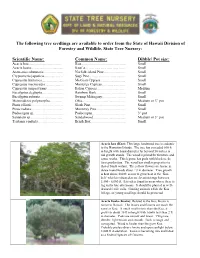

The Following Tree Seedlings Are Available to Order from the State of Hawaii Division of Forestry and Wildlife, State Tree Nursery

The following tree seedlings are available to order from the State of Hawaii Division of Forestry and Wildlife, State Tree Nursery: Scientific Name: Common Name: Dibble/ Pot size: Acacia koa……………………… Koa……………………………….. Small Acacia koaia……………………... Koai’a……………………………. Small Araucaria columnaris…………….. Norfolk-island Pine……………… Small Cryptomeria japonica……………. Sugi Pine………………………… Small Cupressus lusitanica……………... Mexican Cypress………………… Small Cupressus macrocarpa…………… Monterey Cypress……………….. Small Cupressus simpervirens………….. Italian Cypress…………………… Medium Eucalyptus deglupta……………… Rainbow Bark……………………. Small Eucalyptus robusta……………….. Swamp Mahogany……………….. Small Metrosideros polymorpha……….. Ohia……………………………… Medium or 3” pot Pinus elliotii……………………… Slash Pine………………………... Small Pinus radiata……………………... Monterey Pine…………………… Small Podocarpus sp……………………. Podocarpus………………………. 3” pot Santalum sp……………………… Sandalwood……………………… Medium or 3” pot Tristania conferta………………… Brush Box………………………... Small Acacia koa (Koa): This large hardwood tree is endemic to the Hawaiian Islands. The tree has exceeded 100 ft in height with basal diameter far beyond 50 inches in old growth stands. The wood is prized for furniture and canoe works. This legume has pods with black seeds for reproduction. The wood has similar properties to that of black walnut. The yellow flowers are borne in dense round heads about 2@ in diameter. Tree growth is best above 800 ft; seems to grow best in the ‘Koa belt’ which is situated at an elevation range between 3,500 - 6,000 ft. It is often found in areas where there is fog in the late afternoons. It should be planted in well- drained fertile soils. Grazing animals relish the Koa foliage, so young seedlings should be protected Acacia koaia (Koaia): Related to the Koa, Koaia is native to Hawaii. The leaves and flowers are much the same as Koa. -

Farm and Forestry Production and Marketing Profile for Sandalwood (Santalum Species)

Specialty Crops for Pacific Island Agroforestry (http://agroforestry.net/scps) Farm and Forestry Production and Marketing Profile for Sandalwood (Santalum species) By Lex A.J. Thomson, John Doran, Danica Harbaugh, and Mark D. Merlin USES AND PRODUCTS apart from carving, sandalwood is rarely used in many of Wood from the Hawaiian and South Pacific sandalwoods these traditional ways nowadays because of its scarcity and traditionally had a diversity of uses such as carving, medi- economic value. cine, insect repellent when burnt (St. John 1947), and fuel Commercial exploitation of sandalwood commenced in the (Wagner 1986). The grated wood was used to a limited ex- Hawaiian and some South Pacific islands during the late 18th tent to scent coconut oil (for application to the hair and and early 19th centuries when the aromatic lower trunks and body) and cultural artifacts such as tapa cloth (Krauss 1993; rootstock of native Santalum species were harvested in great Kepler 1985). In Hawai‘i, sandalwoods were used to make quantity and shipped to China. There they were used to musical instruments such as the musical bow (‘ūkēkē) and make incense, fine furniture, and other products. The exten- to produce hoe (paddles) as part of traditional canoe con- sive and often exploitative sandalwood trade in Hawai‘i was struction (Buck 1964; Krauss 1993). The highest-value wood an early economic activity that adversely affected both the from the sandalwoods is used for carving (i.e., religious stat- natural environment and human health. Indeed, this activ- ues and objects, handicrafts, art, and decorative furniture). ity represented an early shift from subsistence to commer- For most purposes larger basal pieces and main roots are cial economy in Hawai‘i that was to have far-reaching and preferred due to their high oil content and better oil profiles, long-lasting effects in the islands (Shineberg 1967). -

Hawaiian Santalum Species (Sandalwood)

April 2006 Species Profiles for Pacific Island Agroforestry ver. 4.1 www.traditionaltree.org Santalum ellipticum, S. freycinetianum, S. haleakalae, and S. paniculatum (Hawaiian sandalwood) Santalaceae (sandalwood family) ‘iliahialo‘e (S. ellipticum) ‘iliahi, ‘a‘ahi, ‘aoa, lā‘au ‘ala, wahie ‘ala (S. freycinetianum, S. haleakalae, and S. paniculatum) Mark D. Merlin, Lex A.J. Thomson, and Craig R. Elevitch IN BRIEF Distribution Hawaiian Islands, varies by species. Size Small shrubs or trees, typically 5–10 m photo: M. Merlin M. photo: (16–33 ft) or larger at maturity. Habitat Varies by species; typically xeric, sub humid, or humid tropics with a distinct dry season of 3–5 months. Vegetation Open, drier forests and wood lands. Soils All species require light to medium, well drained soils. Growth rate Slow to moderate, 0.3–0.7 m/yr (1–2.3 ft/yr). Main agroforestry uses Homegardens, mixed species forestry. Main uses Heartwood for crafts, essential oil extraction. Yields Heartwood in 30+ years. Intercropping Because sandalwood is para sitic and requires one or more host plants, intercropping is not only possible but neces sary. Santalum freycinetianum var. Invasive potential Sandalwood has a capac lanaiense, rare, nearly extinct. ity for invasiveness in disturbed areas, but this Photo taken near summit of is rarely considered a problem. Lāna‘ihale, Lāna‘i in 1978. INTRODUCTION SANDALWOOD TERMS Hawaiian sandalwood species are small trees that occur naturally in open, drier forest and woodland communities. Hemi-parasitic Describes a plant that photosynthe They are typically multistemmed and somewhat bushy, at sizes but derives water and some nutrients through at taining a height of 5–10 m (16–33 ft) or larger at maturity, taching to roots of other species.