The Attacks on Japan in 1945, an Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TAU VIOR'la ARMY LIST Tau Vior'la Armies Have a Strategy Rating of 3

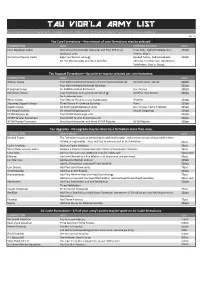

TAU VIOR'LA ARMY LIST Tau Vior'la Armies have a Strategy Rating of 3. Crisis Battlesuit Cadres, XV014, KV128 and the Manta are Initiative 1+; all other formations are Initiative 2+. Dev 1.8 Tau Core Formations—Any amount of core formations may be selected. FORMATION UNITS UPGRADES ALLOWED COST Crisis Battlesuit Cadre One Shas'el Commander character and Four XV8 Crisis Crisis Suits, Cadre Fireblade, Gun 250pts Battlesuit units Drones, Shas'o Vior'la Fire Warrior Cadre Eight Fire Warrior units or Bonded Teams, Cadre Fireblade, 225pts Six Fire Warrior units and three Devilfish Ethereal, Fire Warriors, Gun Drones, Pathfinders, Shas'o, Skyray Tau Support Formations—Up to three may be selected per core formation. FORMATION UNITS COST Armour Group Four Hammerhead (Ionhead) or (Fusionhead) Gunships or Hammerheads, Skyray 200pts Four Hammerhead (Railhead) Gunships 225pts Broadside Group Six XV88 Broadside Battlesuits Gun Drones 300pts Pathfinder Group Four Pathfinder units and two Devilfish or Devilfish, Gun Drones 200pts Six Pathfinder units Recon Group Five Tetra or Piranha, in any combination Piranhas 150pts Skysweep Support Group Three Skyray Air Defence Gunships None 250pts Stealth Group Six XV15 Stealth Battlesuit units Gun Drones, Cadre Fireblade 225pts 0-2 Vespid Swarms Six Vespid Stingwing units Vespid Stingwings 150pts KX128 Stormsurge Two KX128 Stormsurge units 250pts KV129 Ta'unar Supremacy One KV129 Ta'unar Supremacy unit 225pts XV104 Riptide Formation One Shas'el character and three XV104 Riptides XV104 Riptide 350pts Tau Upgrades - No upgrade may be taken by a formation more than once. FORMATION UNITS / EFFECT COST Bonded Teams The formation counts as containing an additional Leader and removes an extra blast marker when rallying or regrouping. -

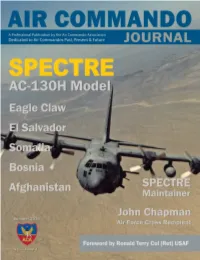

Air Commando JOURNAL Summer 2014 Vol 3, Issue 2 4 Foreword Col (Ret) Ronald Terry 9 AC-130S in Operation Rice

summer 2014.indd 1 7/29/2014 3:32:13 PM OCT 16 - 19 RAMADA BEACH RESORT/FT WALTON BEACH, FL THURSDAY SATURDAY NIGHT BANQUET w Early Bird Social FRIDAY GOLF w Social Hour 1730-1900 w Guests of Honor: Gen (Ret) at Shalimar Pointe FRIDAY w Golf Tournament Norton Schwartz and Golf Club w Fish Fry Mr Kurt Muse w SATURDAY Air Commando Hall of Fame Presentations 85 rooms available at the w Professional Seminar/ Ramada Plaza Beach Resort Business Meeting Breakfast w AFSOC Commander’s located in Ft Walton Beach. w Banquet Leadership Awards Mention Air Commandos to w Entertainment receive a special rate of $99 (first SUNDAY come/first serve) w ACA Open House BANQUET DINNER Call 850-243-9161 to w Memorial Service reserve by Sep 1, 2014. Our dinner features a house salad to w BBQ accompany the entree of garlic blasted chicken breast and shrimp Montreal served with blistered tomato compote along with rosemary Online registration begins July 1st RSVP by Oct 10, 2014 roasted new potatoes, broccoli & carrots. The at www.aircommando.org dessert will be a praline cheesecake. or call 850-581-0099 Dress for Active Duty military is Service Dress Email: [email protected] WWW.AIRCOMMANDO.ORG summer 2014.indd 2 7/29/2014 3:32:14 PM Air Commando JOURNAL Summer 2014 Vol 3, Issue 2 4 Foreword Col (Ret) Ronald Terry 9 AC-130s in Operation Rice Bowl and Eagle Claw AC-130H aircraft #6568 “Night Stalker” crew. 20 16 Operation Continue Hope Bield Kirk and Blinking Light Somalia 1993-94 29 5 OCT 16 - 19 Spectre in Bosnia Chindit Chatter RAMADA BEACH RESORT/FT WALTON BEACH, FL 7 30 Hotwash Spirit 03 and the Golden Age of the Gunship 42 The Spectre Maintainer 35 The Opening Rounds 44 An Everlasting American Legacy ON THE COVER 45 CCT John Chapman AC-130H Spectre at the Battle of Takur Ghar Photo donated to the Air 51 Commando Association by 16th SOS Moving Forward Col (Ret) Sherman ‘Gene’ Eller. -

Raf Bomber Command and No. 6 (Canadian) Group

ANGLO-CANADIAN WARTIME RELATIONS, 1939-1945: RAF BOMBER COMMAND AND NO. 6 (CANADIAN) GROUP By (£) WILLIAMS. CARTER, B.A., M.A. Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University April 1989 ANGLO-CANADIAN WARTIME RELATIONS, 1939-1945: RAF BOMBER COMMAND AND NO. 6 (CANADIAN) GROUP DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (1989) McMASTER UNIVERSITY (History) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Anglo-Canadian Wartime Relations, 1939-1945: RAF Bomber Command and No. 6 (Canadian) Group AUTHOR: Williams. Carter, B.A. (York University) M.A. (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor John P. Campbell NUMBER OF PAGES: viii, 239 ii ABSTRACT In its broadest perspective the following thesis is a case study in Anglo-Canadian relations during the Second World War. The specific subject is the relationship between RAF Bomber Command and No. 6 (Canadian) Group, with emphasis on its political, operational (military), and social aspects. The Prologue describes the bombing raid on Dortmund of 6/7 October, 1944, and has two purposes. The first is to set the stage for the subsequent analysis of the Anglo Canadian relationship and to serve as a reminder of the underlying operational realities. The second is to show to what extent Canadian air power had grown during the war by highlighting the raid that was No. 6 Group's maximum effort of the bombing campaign. Chapter 1 deals with the political negotiations and problems associated with the creation of No. 6 Group on 25 October, 1942. The analysis begins with an account of how the Mackenzie King government placed all RCAF aircrew graduates of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan at iii the disposal of the RAF and then had to negotiate for the right to concentrate RCAF aircrew overseas in their own squadrons and higher formations. -

14 August 1944

Canadian Military History Volume 15 Issue 3 Article 8 2006 Report on the Bombing of Our Own Troops during Operation “Tractable”: 14 August 1944 Arthur T. Harris Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/cmh Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Harris, Arthur T. "Report on the Bombing of Our Own Troops during Operation “Tractable”: 14 August 1944." Canadian Military History 15, 3 (2006) This Feature is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canadian Military History by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Harris: Bombing of Our Own Troops Report on the Bombing of Our Own Troops during Operation “Tractable” – 14 August 1944 Arthur T. Harris Air Chief Marshal, Commanding-in-Chief, Bomber Command Editor’s note: Operation “Tractable” was the second major Canadian operation in Normandy designed to break through the German defensive perimeter to reach Falaise. Like its predecessor, Operation “Totalize,” “Tractable” was to employ heavy bombers to augment the firepower available to the troops. The use of heavy bombers in a tactical role was a relatively new tasking for the strategic force and required precise targetting to destroy and disrupt the enemy positions. The strategic bomber force, British and American, had made significant contributions to the land battle in Normandy, but there had been mistakes, most notably during Operation “Cobra” when the American 8th Air Force had twice bombed their own troops on 24-25 July causing 136 deaths and an additional 621 casualties. -

Berging Short Stirling

Bron: ww2images.com Berging Short Stirling Abdij Lilbosch, eigenaar van de bergingslocatie heeft toestemming gegeven om tot berging over te gaan waar- door we tijdens de festiviteiten van 75 jaar bevrijding in september 2019 de schop in de grond gaat. Berging Short Stirling nabij abdij Lilbosch Short Stirling W7630 De Short Stirling (vernoemd naar de Schotse plaats Stirling) was een Britse bommenwerper gebouwd door Short Brothers. Het was de eerste viermotorige bommenwerper die door de RAF (Royal Air Force) in dienst werd gesteld. Het vliegtuig werd gebouwd van 1939 tot 1943. In totaal zijn er 2383 exemplaren gebouwd. Op de foto ziet u v.l.n.r. Marleen Jennissen (voorzitter Stichting Berging Stirling W7630), Henk Maessen (voorzitter Stichting Op Vleugels der Vrijheid), abt Dom Malachias en wethouder Peter Pustjens. Zij werken in goed overleg samen om dit project in goede banen te leiden. Bemanningsleden Leslie R. Barr; (KIA) Flight Lieute- Irwin D. Fountain; (MIA) Pilot Ernest R.M. Runnacles; (KIA) Pilot Philip G. Freberg; (EVD) Pilot Maurice S. Pepper; (MIA) sergeant Eric H. Cook; (POW) Pilot Officer, John Greenwood; (MIA) sergeant, Peter B.P. Price; (MIA) sergeant, nant DFC & Bar, leeftijd 28 jaar. Hij Officer, leeftijd 27 jaar. Hij was 2de Officer, leeftijd 28 jaar. Hij was Officer, leeftijd 26 jaar. Hij was DFM, leeftijd 27 jaar. Hij was leeftijd 24 jaar. Hij was radio- leeftijd 19 jaar. Hij was rugkoepel- leefttijd 34 jaar. Hij was staart- was 1ste piloot, werd destijds dood piloot en wordt sindsdien vermist. vermoedelijk de bommenrichter, navigator en wist na zijn sprong uit boordwerktuigkundige en wordt telegrafist en werd na zijn sprong schutter en wordt sindsdien schutter en wordt sindsdien aangetroffen op de crashplaats en werd destijds dood aangetroffen handen van de Duitsers te blijven sindsdien vermist. -

Sheet Key.Indd

Sheet Key The worksheets are avalable, on request, from [email protected]. Each worksheet in the 1939–41 file, unlike other data presented on this CD-ROM, is based on a single documentary source that could not be cross-checked against another. Thus, the information in the three worksheets that make up the 1939 and 1941.xls workbook does not match the criteria and specificity of worksheets for 1942–45. The following lists of documents are the sources of the worksheet in file 1939–41.xls: 1. Sir Charles Kingsley Webster and Noble Frankland, The Strategic Air Offensive against Germany, 1939–1945, vol. 4, Annexes and Appendices (London: Her Majesty’s Statio- nery Office, 1961), app. 40 and 41, which include Bomber Command (BC) losses and tonnage by month, September 1939 to May 1941, worksheet 1, BC 1939–41 2. RAF Air Historical Branch Monograph, The RAF in the Bombing Offensive against Germany, vol. 2, app. U 15, May 1940 to 31 May 1941, worksheet 2, BC 1940–41 3. RAF Air Historical Branch Monograph, The RAF in the Bombing Offensive against Germany, vol. 3, app. L1 through L16, Bomber Command operations by day, June 1941 to December 1941, worksheet 3, BC June–December 1941. An explanation for the content of each worksheet’s abbreviation; codes, and other des- ignations follows. Worksheet Columns The following list of abbreviations spells out the names of countries abbreviated in column A of the worksheets: Column A: countries struck by Anglo-American strategic bombers Au = Austria Be = Belgium Bu = Bulgaria Cz = Czechoslovakia De = Denmark -

Royal Air Force Historical Society Journal 28

ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY JOURNAL 28 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. Photographs credited to MAP have been reproduced by kind permission of Military Aircraft Photographs. Copies of these, and of many others, may be obtained via http://www.mar.co.uk Copyright 2003: Royal Air Force Historical Society First published in the UK in 2003 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISSN 1361-4231 Typeset by Creative Associates 115 Magdalen Road Oxford OX4 1RS Printed by Advance Book Printing Unit 9 Northmoor Park Church Road Mothmoor OX29 5UH 3 CONTENTS A NEW LOOK AT ‘THE WIZARD WAR’ by Dr Alfred Price 15 100 GROUP - ‘CONFOUND AND…’ by AVM Jack Furner 24 100 GROUP - FIGHTER OPERATIONS by Martin Streetly 33 D-DAY AND AFTER by Dr Alfred Price 43 MORNING DISCUSSION PERIOD 51 EW IN THE EARLY POST-WAR YEARS – LINCOLNS TO 58 VALIANTS by Wg Cdr ‘Jeff’ Jefford EW DURING THE V-FORCE ERA by Wg Cdr Rod Powell 70 RAF EW TRAINING 1945-1966 by Martin Streetly 86 RAF EW TRAINING 1966-94 by Wg Cdr Dick Turpin 88 SOME THOUGHTS ON PLATFORM PROTECTION SINCE 92 THE GULF WAR by Flt Lt Larry Williams AFTERNOON DISCUSSION PERIOD 104 SERGEANTS THREE – RECOLLECTIONS OF No -

Air Navigation in the Service

A History of Navigation in the Royal Air Force RAF Historical Society Seminar at the RAF Museum, Hendon 21 October 1996 (Held jointly with The Royal Institute of Navigation and The Guild of Air Pilots and Air Navigators) ii The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. Copyright ©1997: Royal Air Force Historical Society First Published in the UK in 1997 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data available ISBN 0 9519824 7 8 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the permission from the Publisher in writing. Typeset and printed in Great Britain by Fotodirect Ltd, Brighton Royal Air Force Historical Society iii Contents Page 1 Welcome by RAFHS Chairman, AVM Nigel Baldwin 1 2 Introduction by Seminar Chairman, AM Sir John Curtiss 4 3 The Early Years by Mr David Page 66 4 Between the Wars by Flt Lt Alec Ayliffe 12 5 The Epic Flights by Wg Cdr ‘Jeff’ Jefford 34 6 The Second World War by Sqn Ldr Philip Saxon 52 7 Morning Discussions and Questions 63 8 The Aries Flights by Gp Capt David Broughton 73 9 Developments in the Early 1950s by AVM Jack Furner 92 10 From the ‘60s to the ‘80s by Air Cdre Norman Bonnor 98 11 The Present and the Future by Air Cdre Bill Tyack 107 12 Afternoon Discussions and -

An Assessment of the Development of Target Marking Techniques to the Prosecution of the Bombing Offensive During the Second World War

Circumventing the law that humans cannot see in the dark: an assessment of the development of target marking techniques to the prosecution of the bombing offensive during the Second World War Submitted by Paul George Freer to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in August 2017 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: Paul Freer 1 ABSTRACT Royal Air Force Bomber Command entered the Second World War committed to a strategy of precision bombing in daylight. The theory that bomber formations would survive contact with the enemy was soon dispelled and it was obvious that Bomber Command would have to switch to bombing at night. The difficulties of locating a target at night soon became apparent. In August 1941, only one in three of those crews claiming to have bombed a target had in fact had been within five miles of it. And yet, less than four years later, it would be a very different story. By early 1945, 95% of aircraft despatched bombed within 3 miles of the Aiming Point and the average bombing error was 600 yards. How, then, in the space of four years did Bomber Command evolve from an ineffective force failing even to locate a target to the formidable force of early 1945? In part, the answer lies in the advent of electronic navigation aids that, in 1941, were simply not available. -

The Halifax and Lancaster in Canadian Service

Canadian Military History Volume 15 Issue 3 Article 2 2006 The Halifax and Lancaster in Canadian Service Stephen J. Harris Directorate of Heritage and History, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/cmh Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Harris, Stephen J. "The Halifax and Lancaster in Canadian Service." Canadian Military History 15, 3 (2006) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canadian Military History by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Harris: The Halifax and Lancaster The Halifax and Lancaster in Canadian Service Stephen J. Harris n our early discussions on the bomber section rate aircraft. I had to know how clapped out Iof The Crucible of War, the third volume of Halifaxes were; and I had to find out whether the official history of the Royal Canadian Air the allocation of aircraft was biased along Force, Ben Greenhous and I wondered whether national lines. What I found was that Harris we should adopt a chronological or topical exaggerated somewhat; that he did not allocate organisation. I preferred the latter; Ben the aircraft on national lines; and, perhaps not former. He was the principal author; he got his surprisingly, that bomber crews who survived a way – he was right, of course, I now admit freely; tour on Halifaxes were quite happy with their and his instructions to me were “to write an aircraft. Why not? They made it through. -

Bombing the European Axis Powers a Historical Digest of the Combined Bomber Offensive 1939–1945

Inside frontcover 6/1/06 11:19 AM Page 1 Bombing the European Axis Powers A Historical Digest of the Combined Bomber Offensive 1939–1945 Air University Press Team Chief Editor Carole Arbush Copy Editor Sherry C. Terrell Cover Art and Book Design Daniel M. Armstrong Composition and Prepress Production Mary P. Ferguson Quality Review Mary J. Moore Print Preparation Joan Hickey Distribution Diane Clark NewFrontmatter 5/31/06 1:42 PM Page i Bombing the European Axis Powers A Historical Digest of the Combined Bomber Offensive 1939–1945 RICHARD G. DAVIS Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama April 2006 NewFrontmatter 5/31/06 1:42 PM Page ii Air University Library Cataloging Data Davis, Richard G. Bombing the European Axis powers : a historical digest of the combined bomber offensive, 1939-1945 / Richard G. Davis. p. ; cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-58566-148-1 1. World War, 1939-1945––Aerial operations. 2. World War, 1939-1945––Aerial operations––Statistics. 3. United States. Army Air Forces––History––World War, 1939- 1945. 4. Great Britain. Royal Air Force––History––World War, 1939-1945. 5. Bombing, Aerial––Europe––History. I. Title. 940.544––dc22 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Book and CD-ROM cleared for public release: distribution unlimited. Air University Press 131 West Shumacher Avenue Maxwell AFB AL 36112-6615 http://aupress.maxwell.af.mil ii NewFrontmatter 5/31/06 1:42 PM Page iii Contents Page DISCLAIMER . -

Hitting Home the Air Offensive Against Japan

The U.S. Army Air Forces in World War II Hitting Home The Air Offensive Against Japan Daniel L. Haulman AIR FORCE HISTORY AND MUSEUMS PROGRAM 1999 Hitting Home The Air Offensive Against Japan The strategic bombardment of Japan during World War II remains one of the most controversial subjects of military history because it involved the first and only use of atomic weapons in war. It also raised the question of whether strategic bombing alone can win wars, a question that dominated U.S. Air Force thinking for a generation. Without question, the strategic bombing of Japan contributed very heavily to the Japanese decision to surrender. The United States and her allies did not have to invade the home islands, an invasion that would have cost many thousands of lives on both sides. This pamphlet traces the development of the bombing of the Japan- ese home islands, from the modest but dramatic Doolittle raid on Tokyo in April 1942, through the effort to bomb from bases in China that were supplied by airlift over the Himalayas, to the huge 500-plane raids from the Marianas in the Pacific. The campaign changed from precision daylight bombing to night incendiary bombing of Japanese cities and ultimately to the use of atomic bombs against Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The story covers the debut of the spectacular B–29 air- craft—in many ways the most awesome weapon of World War II— and its use not only as a bomber but also as a mine-layer. Hitting Home is the sequel to High Road to Tokyo Bay, a pamphlet by the same author that concentrated on Army Air Forces’ tactical op- erations in Asia and the Pacific areas during World War II.