Servomechanisms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Control of DC Servomotor

Control of DC Servomotor Report submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement to the degree of B.SC In Electrical and Electronic Engineering Under the supervision of Dr. Abdarahman Ali Karrar By Mohammed Sami Hassan Elhakim To Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering University of Khartoum July 2008 Dedication I would like to take this opportunity to write these humble words that are unworthy of expressing my deepest gratitude for all those who made this possible. First of all I would like to thank god for my general existence and everything else around and within me. Second I would like to thank my beloved parents(Sami & Sawsan), my brothers (Tarig & Hassan), and my sister (Latifa), thank you so much for your support, guidance and care, you were always there to make me feel better and encourage me. I would like also to thanks all my friends inside and out Khartoum university, thank you for your patients tolerance and understanding, for your endless love that has stretched so far, for easing my pain and pulling me through. A special thanks to my partner Muzaab Hashiem without his help and advice i won’t be able to do what i did, thank you for being an ideal partner, friend and bother. Last but not the least i would like to thank my supervisor Dr. Karar and all those who helped me throughout this project, thank you for filling my mind with this rich knowledge. Mohammed Sami Hassan Elhakim. I Acknowledgement The first word goes to God the Almighty for bringing me to this world and guiding me as i reached this stage in my life and for making me live and see this work. -

Glossary Defns of Terms 1998-10 TWG INCOSE .Doc

INCOSE SE Terms Glossary Version 0 October 1998 INCOSE SE Terms Glossary Document No.: TBD Version/Revision: 0 Date: October, 1998 File: Glossary Defns of Terms 1998-10 TWG INCOSE .doc Prepared by: INCOSE Concepts and Terms WG International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE) 2150 N. 107th Street, Suite 205 Seattle, WA 98133-9009 NOTICE This data was prepared by the Terminology Working Group of the International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE) for review and comment only. It is has been released by that agency as INCOSE Technical Data. It is subject to change without notice and may not be referred to as an INCOSE Technical Product. Copyright (c) 1998 by INCOSE, subject to the following restrictions: Author Use. Authors have full rights to use their contributions in a totally unfettered way. Abstraction is permitted with credit to the source. INCOSE Use. Permission to reproduce and use this document and to prepare derivative works from this document for INCOSE use is granted, provided this copyright notice is included with all reproductions and derivative works. External Use. This document may not be shared or distributed to any non-INCOSE third party. Requests for permission to reproduce this document in whole or part, or to prepare derivative works of this document for external and/or commercial use are prohibited. Copying, scanning, retyping, or any other form of reproduction of the content of whole pages or source documents is prohibited and shall not be approved by INCOSE. Electronic Version Use. Any electronic version of this document is to be used for personal use only and is not to be placed on a non-INCOSE sponsored server for general use. -

Course Description Bachelor of Technology (Electrical Engineering)

COURSE DESCRIPTION BACHELOR OF TECHNOLOGY (ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING) COLLEGE OF TECHNOLOGY AND ENGINEERING MAHARANA PRATAP UNIVERSITY OF AGRICULTURE AND TECHNOLOGY UDAIPUR (RAJASTHAN) SECOND YEAR (SEMESTER-I) BS 211 (All Branches) MATHEMATICS – III Cr. Hrs. 3 (3 + 0) L T P Credit 3 0 0 Hours 3 0 0 COURSE OUTCOME - CO1: Understand the need of numerical method for solving mathematical equations of various engineering problems., CO2: Provide interpolation techniques which are useful in analyzing the data that is in the form of unknown functionCO3: Discuss numerical integration and differentiation and solving problems which cannot be solved by conventional methods.CO4: Discuss the need of Laplace transform to convert systems from time to frequency domains and to understand application and working of Laplace transformations. UNIT-I Interpolation: Finite differences, various difference operators and theirrelationships, factorial notation. Interpolation with equal intervals;Newton’s forward and backward interpolation formulae, Lagrange’sinterpolation formula for unequal intervals. UNIT-II Gauss forward and backward interpolation formulae, Stirling’s andBessel’s central difference interpolation formulae. Numerical Differentiation: Numerical differentiation based on Newton’sforward and backward, Gauss forward and backward interpolation formulae. UNIT-III Numerical Integration: Numerical integration by Trapezoidal, Simpson’s rule. Numerical Solutions of Ordinary Differential Equations: Picard’s method,Taylor’s series method, Euler’s method, modified -

Power Processing, Part 1. Electric Machinery Analysis

DOCONEIT MORE BD 179 391 SE 029 295,. a 'AUTHOR Hamilton, Howard B. :TITLE Power Processing, Part 1.Electic Machinery Analyiis. ) INSTITUTION Pittsburgh Onii., Pa. SPONS AGENCY National Science Foundation, Washingtcn, PUB DATE 70 GRANT NSF-GY-4138 NOTE 4913.; For related documents, see SE 029 296-298 n EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 PusiPostage. DESCRIPTORS *College Science; Ciirriculum Develoiment; ElectricityrFlectrOmechanical lechnology: Electronics; *Fagineering.Education; Higher Education;,Instructional'Materials; *Science Courses; Science Curiiculum:.*Science Education; *Science Materials; SCientific Concepts ABSTRACT A This publication was developed as aportion of a two-semester sequence commeicing ateither the sixth cr'seventh term of,the undergraduate program inelectrical engineering at the University of Pittsburgh. The materials of thetwo courses, produced by a ional Science Foundation grant, are concernedwith power convrs systems comprising power electronicdevices, electrouthchanical energy converters, and associated,logic Configurations necessary to cause the system to behave in a prescribed fashion. The emphisis in this portionof the two course sequence (Part 1)is on electric machinery analysis. lechnigues app;icable'to electric machines under dynamicconditions are anallzed. This publication consists of sevenchapters which cW-al with: (1) basic principles: (2) elementary concept of torqueand geherated voltage; (3)tile generalized machine;(4i direct current (7) macrimes; (5) cross field machines;(6),synchronous machines; and polyphase -

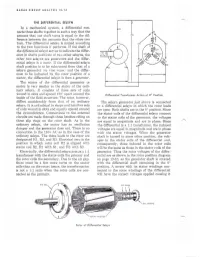

In a Mechanical System, a Differential

RADAR CIRCUIT ANALYSIS 13-14 THE DIFFERENTIAL SElSYN In a mechanical system, a differential con- 52 nects three shafts together in such a way that the amount that one shaft turns is equal to the dif- zsv ference between the amounts that the other two turn. The differential selsyn is named according to the two functions it performs. If the shaft of the differential selsyn serves to indicate the differ- ence in shafts positions of two other selsyns, the other two selsyns are generators and the differ- ential selsyn is a motor. If the differential selsyn shaft position is to be subtracted from that of a 53 selsyn generator (or vice versa) and the differ- ence to be indicated by the rotor position of a i----OV---o-i motor, the differential selsyn is then a generator. ~---OV--~~_-4 ~ The stator of the differential generator or motor is very similar to the stator of the ordi- nary selsyn. It consists of three sets of coils 0 wound in slots and spaced 120 apart around the Differential Transformer Action at 0° Position inside of the field structure. The rotor, however, differs considerably from that of an ordinary The selsyn generator just above is connected selsyn. It is cylindrical in shape and has three sets to a differential selsyn in which the rotor leads of coils wound in slots and equally spaced around are open. Both shafts are in the 0° position. Since the circumference. Connections to the external the stator coils of the differential selsyn connect circuits are made through three brushes riding on to the stator coils of the generator, the voltages three slip rings on the rotor shaft. -

Brushless DC Electric Motor

Please read: A personal appeal from Wikipedia author Dr. Sengai Podhuvan We now accept ₹ (INR) Brushless DC electric motor From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search A microprocessor-controlled BLDC motor powering a micro remote-controlled airplane. This external rotor motor weighs 5 grams, consumes approximately 11 watts (15 millihorsepower) and produces thrust of more than twice the weight of the plane. Contents [hide] 1 Brushless versus Brushed motor 2 Controller implementations 3 Variations in construction 4 AC and DC power supplies 5 KM rating 6 Kv rating 7 Applications o 7.1 Transport o 7.2 Heating and ventilation o 7.3 Industrial Engineering . 7.3.1 Motion Control Systems . 7.3.2 Positioning and Actuation Systems o 7.4 Stepper motor o 7.5 Model engineering 8 See also 9 References 10 External links Brushless DC motors (BLDC motors, BL motors) also known as electronically commutated motors (ECMs, EC motors) are electric motors powered by direct-current (DC) electricity and having electronic commutation systems, rather than mechanical commutators and brushes. The current-to-torque and frequency-to-speed relationships of BLDC motors are linear. BLDC motors may be described as stepper motors, with fixed permanent magnets and possibly more poles on the rotor than the stator, or reluctance motors. The latter may be without permanent magnets, just poles that are induced on the rotor then pulled into alignment by timed stator windings. However, the term stepper motor tends to be used for motors that are designed specifically to be operated in a mode where they are frequently stopped with the rotor in a defined angular position; this page describes more general BLDC motor principles, though there is overlap. -

EE 3TP4: Signals and Systems Lab 5: Control of a Servomechanism Tim Davidson Ext

EE 3TP4: Signals and Systems Lab 5: Control of a Servomechanism Tim Davidson Ext. 27352 [email protected] Objective To identify the plant model of a servomechanism, and explore the trade-off between rise time and overshoot incurred in proportional control of the servo(mechanism). Assessment Your mark for this lab will be assessed on your ability to complete each section. The marks for each section are indicated at the beginning of the section. Please demonstrate your results to the TAs and have your mark recorded. Please attend the lab section to which you have been assigned. 1 Description of Laboratory Equipment In this lab we will deal with an angular positioning system based around a DC motor. Such schemes are often used to position heavy or difficult to move objects using a ‘command tool’ which is easy to move. For example, moving the control surfaces of an aircraft using the lever in the cockpit. In our system, the plant is the motor (and its associated electronics). The input to the plant is a control signal c(t) and the output of the plant is a voltage which is proportional to the angle of the motor shaft, θ(t). Using information about the structure of the motor and Newtonian mechanics, the operation of the motor can be described by the following differential equation: d2θ(t) dθ(t) J + B = Kmc(t); (1) dt2 dt where J is the rotational inertia of the motor, B is the damping in the motor structure, and Km is the (internal) gain of the motor. -

Servo Systems

2012/3/26 Servo Systems Department of Mechanical Engineering Lecturer: Jia-Yush Yen 4/7/2010 A Control System Reference command Output Controller Actuator Plant Measurement Servo Systems 2 1 2012/3/26 Outline • Motors – Synchronous motor – Induction motor – DC motor –BLDC –PMAC – PWM principle – Driver design Servo Systems 3 Servo vs. Process System •A servomechanism is a feedback control system in which the controlled variable is a (mechanical) position, velocity, torque, frequency, etc. •A process control generally refers to control of other variables as liquid level, pressure, temperature, density, concentration, or chemical composition. Servo Systems 4 2 2012/3/26 Servo System Loop Set Point Network http://www.a-m- c.com/content/m101/generalservosystems. Servo Systems html 5 Motors http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Motor • Electric motor – a machine that converts electricity into a mechanical motion – AC motor, an electric motor that is driven by alternating current • Synchronous motor • Induction motor – DC motor, an electric motor that runs on direct current electricity • Brushed DC electric motor • Brushless DC motor – Linear motor – Stepper motor • Servo motor – an electric motor that operates a servo, Servocommonly Systems used in robotics 6 3 2012/3/26 Calculating Magnetic Field • Magnetic Field Intensity: where μ is the permeability • Magnetomotive force (mmf): Servo Systems 7 AC SYNCHRONOUS MOTOR Servo Systems 8 4 2012/3/26 AC Synchronous Motor • A synchronous electric motor is an AC motor distinguished by a rotor spinning with coils passing magnets at the same rate as the alternating current and resulting magnetic field which drives it. Another way of saying this is that it has zero slip under usual operating conditions http://www.mwit.ac.th/~Phy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sy sicslab/hbase/magnetic/mo nchronous_motor torac.html Servo Systems 9 Rotating Magnetic Field • Apply three-phase voltage to a three-phase stator winding creates a rotating field. -

London Electricity Companies Had Already Supply Co

printed LONDON AREA POWER SUPPLY A Survey of London’s Electric Lighting and Powerbe Stations By M.A.C. Horne to - not Copyright M.A.C. Horne © 2012 (V3.0) London’s Power Supplies LONDON AREA POWER SUPPLY Background to break up streets and to raise money for electric lighting schemes. Ignoring a small number of experimental schemes that did not Alternatively the Board of Trade could authorise private companies to provide supplies to which the public might subscribe, the first station implement schemes and benefit from wayleave rights. They could that made electricity publicly available was the plant at the Grosvenor either do this by means of 7-year licences, with the support of the Art Gallery in New Bond Street early in 1883. The initial plant was local authority, or by means of a provisional order which required no temporary, provided from a large wooden hut next door, though a local authority consent. In either case the local authority had the right supply was soon made available to local shopkeepers. Demand soon to purchase the company concerned after 21 years (or at 7-year precipitated the building of permanent plant that was complete by intervals thereafter) and to regulate maximum prices. There was no December 1884. The boiler house was on the south side of the power to supply beyond local authority areas or to interconnect intervening passage called Bloomfield Street and was connected with systems. It is importantprinted to note that the act did not prevent the generating plant in the Gallery’s basement by means of an creation of supply companies which could generate and distribute underground passage. -

Introduction

Introduction The Servo Trigger is a small board that helps you deploy hobby RC servo motors. When an external switch or logic signal changes state, the Servo Trigger tells an attached servo motor to move from position A to position B. The Servo Trigger in action. To use the Servo Trigger, you simply connect a hobby servo and a switch, then use the onboard potentiometers to adjust the start/stop positions and transition time. You can use a hobby servos in your projects without having to do any programming! In This Tutorial This hookup guide starts with some background information about hobby servo motors. From there, it jumps into getting the Servo Trigger working with a small servo, then examines some of the inner workings. Finally, for the adventurous, it explains how to customize the Servo Trigger by reprogramming it. Servo Motor Background In the most generic sense, a “servomechanism” (servo for short) is a device that uses feedback to achieve the desired result. Feedback control is used in many different disciplines, controlling parameters such as speed, position, and temperature. In the context we are discussing here, we are talking about hobby or radio-control servo motors. These are small motors primarily used for steering radio-controlled vehicles. Because the position is easily controllable, they are also useful for robotics and animatronics. However, they shouldn’t be confused with other types of servo motors, such as the large ones used in industrial machinery. An Assortment of Hobby Servos RC servos are reasonably standardized - they are all a similar shape, with mounting flanges at each end, available in graduated sizes. -

Electrical Engineering Dictionary

ratio of the power per unit solid angle scat- tered in a specific direction of the power unit area in a plane wave incident on the scatterer R from a specified direction. RADHAZ radiation hazards to personnel as defined in ANSI/C95.1-1991 IEEE Stan- RS commonly used symbol for source dard Safety Levels with Respect to Human impedance. Exposure to Radio Frequency Electromag- netic Fields, 3 kHz to 300 GHz. RT commonly used symbol for transfor- mation ratio. radial basis function network a fully R-ALOHA See reservation ALOHA. connected feedforward network with a sin- gle hidden layer of neurons each of which RL Typical symbol for load resistance. computes a nonlinear decreasing function of the distance between its received input and Rabi frequency the characteristic cou- a “center point.” This function is generally pling strength between a near-resonant elec- bell-shaped and has a different center point tromagnetic field and two states of a quan- for each neuron. The center points and the tum mechanical system. For example, the widths of the bell shapes are learned from Rabi frequency of an electric dipole allowed training data. The input weights usually have transition is equal to µE/hbar, where µ is the fixed values and may be prescribed on the electric dipole moment and E is the maxi- basis of prior knowledge. The outputs have mum electric field amplitude. In a strongly linear characteristics, and their weights are driven 2-level system, the Rabi frequency is computed during training. equal to the rate at which population oscil- lates between the ground and excited states. -

Servo Control Design - Timothy Chang

CONTROL SYSTEMS, ROBOTICS AND AUTOMATION - Vol. VIII - Servo Control Design - Timothy Chang SERVO CONTROL DESIGN Timothy Chang New Jersey Institute of Technology, Newark, NJ, USA Keywords: servo control, servomechanism, feedback, feedforward control, regulation, disturbance rejection, compensation, input shaping, lag compensator, lead compensation, phase margin, steady-state error, integral control, industrial regulator, stabilizing compensator, PID control, state feedback, frequency response, parameter optimization. Contents 1. Introduction 2. Classical Servo Control Design 2.1. Integrator Based Control 2.1.1. Design Example: Industrial Regulator 2.2. Phase Lag Control 2.2.1. Design Example: Phase Lag Compensation 2.3. Phase Lead Control 2.3.1. Design Example: Phase Lead Compensation 3. Modern Servo Control Design 3.1. Feedforward Control: Input Shaping 3.1.1. Mathematical Analysis of the Input Shaping Scheme 3.1.2. Design Example: Input Shaping for Unit Step Command 3.2. Feedback Control 3.2.1. Controller Parameterization 3.2.2. Time Domain Parameter Optimization 3.2.3. Frequency Domain Parameter Optimization 4. Conclusions Acknowledgements Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch Summary UNESCO – EOLSS Elements and design of servo control systems are discussed in this paper. The primary purpose of a servoSAMPLE system is to regulate the outputCHAPTERS of a dynamical system by means of feedback control. For pedagogical and historical reasons, the discussions of servo control are divided into two parts: classical and modern servo systems aiming at audience with an undergraduate and graduate level of engineering background respectively. Classical servo control deals with single-input, single-output systems in either frequency or time domain. It remains popular with many industrial applications due to its simplicity in design and implementation.