Know Thyself? Did Phrenology Help William Powell Frith Address Middle- Class Victorian Crowd Anxiety?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hubert Herkomer, William Powell Frith, and the Artistic Advertisement

Andrea Korda “The Streets as Art Galleries”: Hubert Herkomer, William Powell Frith, and the Artistic Advertisement Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 11, no. 1 (Spring 2012) Citation: Andrea Korda, “‘The Streets as Art Galleries’: Hubert Herkomer, William Powell Frith, and the Artistic Advertisement,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 11, no. 1 (Spring 2012), http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/spring12/korda-on-the-streets-as-art-galleries-hubert- herkomer-william-powell-frith-and-the-artistic-advertisement. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art. Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. Korda: Hubert Herkomer, William Powell Frith, and the Artistic Advertisement Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 11, no. 1 (Spring 2012) “The Streets as Art Galleries”: Hubert Herkomer, William Powell Frith, and the Artistic Advertisement by Andrea Korda By the second half of the nineteenth century, advertising posters that plastered the streets of London were denounced as one of the evils of modern life. In the article “The Horrors of Street Advertisements,” one writer lamented that “no one can avoid it.… It defaces the streets, and in time must debase the natural sense of colour, and destroy the natural pleasure in design.” For this observer, advertising was “grandiose in its ugliness,” and the advertiser’s only concern was with “bigness, bigness, bigness,” “crudity of colour” and “offensiveness of attitude.”[1] Another commentator added to this criticism with more specific complaints, describing the deficiencies in color, drawing, composition, and the subjects of advertisements in turn. Using adjectives such as garish, hideous, reckless, execrable and horrible, he concluded that advertisers did not aim to appeal to the intellect, but only aimed to attract the public’s attention. -

Calendar of Events

Calendar the September/October 2010 hrysler of events CTHE MAGAZINE OF THE CHRYSLER MUSEUM OF ART p 5 Exhibitions • p 7 News • p 10 Daily Calendar • p 14 Public Programs • p 18 Member Programs G ENERAL INFORMATION COVER Contact Us The Museum Shop Group and School Tours William Powell Frith Open during Museum hours (English, 1819–1909) Chrysler Museum of Art (757) 333-6269 The Railway 245 W. Olney Road (757) 333-6297 www.chrysler.org/programs.asp Station (detail), 1862 Norfolk, VA 23510 Oil on canvas Phone: (757) 664-6200 Cuisine & Company Board of Trustees Courtesy of Royal Fax: (757) 664-6201 at The Chrysler Café 2010–2011 Holloway Collection, E-mail: [email protected] Wednesdays, 11 a.m.–8 p.m. Shirley C. Baldwin University of London Website: www.chrysler.org Thursdays–Saturdays, 11 a.m.–3 p.m. Carolyn K. Barry Sundays, 12–3 p.m. Robert M. Boyd Museum Hours (757) 333-6291 Nancy W. Branch Wednesday, 10 a.m.–9 p.m. Macon F. Brock, Jr., Chairman Thursday–Saturday, 10 a.m.–5 p.m. Historic Houses Robert W. Carter Sunday, 12–5 p.m. Free Admission Andrew S. Fine The Museum galleries are closed each The Moses Myers House Elizabeth Fraim Monday and Tuesday, as well as on 323 E. Freemason St. (at Bank St.), Norfolk David R. Goode, Vice Chairman major holidays. The Norfolk History Museum at the Cyrus W. Grandy V Marc Jacobson Admission Willoughby-Baylor House 601 E. Freemason Street, Norfolk Maurice A. Jones General admission to the Chrysler Museum Linda H. -

A Field Awaits Its Next Audience

Victorian Paintings from London's Royal Academy: ” J* ml . ■ A Field Awaits Its Next Audience Peter Trippi Editor, Fine Art Connoisseur Figure l William Powell Frith (1819-1909), The Private View of the Royal Academy, 1881. 1883, oil on canvas, 40% x 77 inches (102.9 x 195.6 cm). Private collection -15- ALTHOUGH AMERICANS' REGARD FOR 19TH CENTURY European art has never been higher, we remain relatively unfamiliar with the artworks produced for the academies that once dominated the scene. This is due partly to the 20th century ascent of modernist artists, who naturally dis couraged study of the academic system they had rejected, and partly to American museums deciding to warehouse and sell off their academic holdings after 1930. In these more even-handed times, when seemingly everything is collectible, our understanding of the 19th century art world will never be complete if we do not look carefully at the academic works prized most highly by it. Our collective awareness is growing slowly, primarily through closer study of Paris, which, as capital of the late 19th century art world, was ruled not by Manet or Monet, but by J.-L. Gerome and A.-W. Bouguereau, among other Figure 2 Frederic Leighton (1830-1896) Study for And the Sea Gave Up the Dead Which Were in It: Male Figure. 1877-82, black and white chalk on brown paper, 12% x 8% inches (32.1 x 22 cm) Leighton House Museum, London Figure 3 Frederic Leighton (1830-1896) Elisha Raising the Son of the Shunamite Woman 1881, oil on canvas, 33 x 54 inches (83.8 x 137 cm) Leighton House Museum, London -16- J ! , /' i - / . -

Wilde's World

Wilde’s World Anne Anderson Aesthetic London Wilde appeared on London’s cultural scene at a propitious moment; with the opening of the Grosvenor Gallery in May 1877 the Aesthetes gained the public platform they had been denied. Sir Coutts Lindsay and his wife Blanche, who were behind this audacious enterprise, invited Edward Burne-Jones, George Frederick Watts, and James McNeill Whistler to participate in the first exhibition; all had suffered rejections from the Royal Academy.1 The public were suddenly confronted with the avant-garde, Pre-Raphaelitism, Symbolism, and even French Naturalism. Wilde immediately recognized his opportunity, as few would understand “Art for Art’s sake,” that paintings no longer had to be didactic or moralizing. Rather, the function of art was to appeal to the senses, to focus on color, form, and composition. Moreover, the aesthetes blurred the distinction between the fine and decorative arts, transforming wallpapers and textiles into objets d’art. The goal was to surround oneself with beauty, to create a House Beautiful. Wilde hitched his star to Aestheticism while an undergraduate at Oxford; his rooms were noted for their beauty, the panelled walls thickly hung with old engravings and contemporary prints by Burne-Jones and filled with exquisite objects: Blue and White Oriental porcelain, Tanagra statuettes brought back from Greece, and Persian rugs. He was also aware of the controversy surrounding Aestheticism; debated in the Oxford and Cambridge Undergraduate in April and May 1877, the magazine at first praised the movement as a civilizing influence. It quickly recanted, as it sought “‘implicit sanction’” for “‘Pagan worship of bodily form and beauty’” and renounced morals in the name of liberty (Ellmann 85, emphasis in original). -

Iconic Images: the Stories They Tell

Curriculum Units by Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute 2011 Volume I: Writing with Words and Images Iconic Images: The Stories They Tell Curriculum Unit 11.01.06 by Kristin M. Wetmore Introduction An important dilemma for me as an art history teacher is how to make the evidence that survives from the past an interesting subject of discussion and learning for my classroom. For the art historian, the evidence is the artwork and the documents that support it. My solution is to have students compare different approaches to a specific historical period because they will have the chance to read primary sources about each of the three images selected, discuss them, and then determine whether and how they reveal, criticize or correctly report the events that they depict. Students should be able to identify if the artist accurately represents an historical event and, if it is not accurately represented, what message the artist is trying to convey. Artists and historians interpret historical events. I would like my students to understand that this interpretation is a construction. Primary documents provide us with just one window to view history. Artwork is another window, but the students must be able to judge on their own the factual content of the work and the artist's intent. It is imperative that students understand this. Barber says in History beyond the Text that there is danger in confusing history as an actual narrative and "construction of the historians (or artist's) craft." 1 The Merriam Webster Dictionary defines iconic as "an emblem or a symbol." 2 The three images I have chosen to study are considered iconic images from the different time periods they represent. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting Template

THE IDEAL OF THE REAL: MID-VICTORIAN REPRESENTATIONS OF THE ARTIST AND THE INVENTION OF REALISM By DANIEL SCHULTZ BROWN A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2012 1 © 2012 Daniel Schultz Brown 2 To my advisor, Pamela Gilbert: for tireless patience, steadfast support and gentle guidance 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS page LIST OF FIGURES .......................................................................................................... 6 ABSTRACT ..................................................................................................................... 7 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 11 History of Realism ................................................................................................... 14 Overview of Critical Literature ................................................................................. 21 Chapter Overview ................................................................................................... 34 2 “LESS EASILY DEFINED THAN APPREHENDED”: MID-VICTORAIN THEORIES OF REALISM ....................................................................................... 41 John Ruskin ............................................................................................................ 45 George Henry Lewes ............................................................................................. -

Three Centuries of British Art

Three Centuries of British Art Three Centuries of British Art Friday 30th September – Saturday 22nd October 2011 Shepherd & Derom Galleries in association with Nicholas Bagshawe Fine Art, London Campbell Wilson, Aberdeenshire, Scotland Moore-Gwyn Fine Art, London EIGHTEENTH CENTURY cat. 1 Francis Wheatley, ra (1747–1801) Going Milking Oil on Canvas; 14 × 12 inches Francis Wheatley was born in Covent Garden in London in 1747. His artistic training took place first at Shipley’s drawing classes and then at the newly formed Royal Academy Schools. He was a gifted draughtsman and won a number of prizes as a young man from the Society of Artists. His early work consists mainly of portraits and conversation pieces. These recall the work of Johann Zoffany (1733–1810) and Benjamin Wilson (1721–1788), under whom he is thought to have studied. John Hamilton Mortimer (1740–1779), his friend and occasional collaborator, was also a considerable influence on him in his early years. Despite some success at the outset, Wheatley’s fortunes began to suffer due to an excessively extravagant life-style and in 1779 he travelled to Ireland, mainly to escape his creditors. There he survived by painting portraits and local scenes for patrons and by 1784 was back in England. On his return his painting changed direction and he began to produce a type of painting best described as sentimental genre, whose guiding influence was the work of the French artist Jean-Baptiste Greuze (1725–1805). Wheatley’s new work in this style began to attract considerable notice and in the 1790’s he embarked upon his famous series of The Cries of London – scenes of street vendors selling their wares in the capital. -

John Leech His Life and Work Vol Ii William Powell Frith, R.A

JOHN LEECH HIS LIFE AND WORK VOL II WILLIAM POWELL FRITH, R.A. CHAPTER I. "PUNCH." In the year 1841 I exhibited a picture at the Suffolk Street Gallery, and I recollect accidentally overhearing fragments of a conversation between a certain Joe Allen and a brother member of the Society of British Artists in Suffolk Street. Allen's picture happened to hang near mine, and we were both "touching up" our productions. Joe Allen was the funny man of the society, and, though he startled me a little, he did not surprise me by a loud and really good imitation of the peculiar squeak of Punch. "Look out, my boy," he said to his friend, "for the first number. We" (I suppose he was a member of the first staff) "shall take the town by storm. There is no mistake about it. We have so-and-so"—naming some well-known men—"for writers; Hine, Kenny Meadows, young Leech, and a lot more first-rate illustrators," etc. Whether Allen's friend took his advice and bought the first number of Punch, which appeared in the following July, I know not; but I bought a copy, and remember my disappointment at finding Leech conspicuous by his absence from the pages. In the hope of finding him in the second issue, I went to the shop where I had bought the first. The shopman met my request for the second number of Punch, as well as I can recollect, in the following words: "What paper, sir? Oh, Punch! Yes, I took a few of the first; but it's no go. -

PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY from the Victorians to the Present Day

PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY From the Victorians to the present day Information and Activities for Secondary Teachers of Art and Photography John French Lord Snowdon, vintage bromide print, 1957 NPG P809 © SNOWDON / Camera Press Information and Activities for Secondary Teachers of Art and Photography Contents Introduction 3 Discussion questions 4 Wide Angle 1. Technical beginnings and early photography Technical beginnings 5 Early photography 8 Portraits on light sensitive paper 11 The Carte-de-visite and the Album 17 2. Art and photography; the wider context Art and portrait photography 20 Photographic connections 27 Technical developments and publishing 32 Zoom 1. The photographic studio 36 2. Contemporary photographic techniques 53 3. Self image: Six pairs of photographic self-portraits 63 Augustus Edwin John; Constantin Brancusi; Frank Owen Dobson Unknown photographer, bromide press print, 1940s NPG x20684 Teachers’ Resource Portrait Photography National Portrait Gallery 3 /69 Information and Activities for Secondary Teachers of Art and Photography Introduction This resource is for teachers of art and photography A and AS level, and it focuses principally on a selection of the photographic portraits from the Collection of the National Portrait Gallery, London which contains over a quarter of a million images. This resource aims to investigate the wealth of photographic portraiture and to examine closely the effect of painted portraits on the technique of photography invented in the nineteenth century. This resource was developed by the Art Resource Developer in the Learning Department in the Gallery, working closely with staff who work with the Photographs Collection to produce a detailed and practical guide for working with these portraits. -

The Summer Exhibition 3

ART HISTORY REVEALED Dr. Laurence Shafe This course is an eclectic wander through art history. It consists of twenty two-hour talks starting in September 2018 and the topics are largely taken from exhibitions held in London during 2018. The aim is not to provide a guide to the exhibition but to use it as a starting point to discuss the topics raised and to show the major art works. An exhibition often contains 100 to 200 art works but in each two-hour talk I will focus on the 20 to 30 major works and I will often add works not shown in the exhibition to illustrate a point. References and Copyright • The talks are given to a small group of people and all the proceeds, after the cost of the hall is deducted, are given to charity. • The notes are based on information found on the public websites of Wikipedia, Tate, National Gallery, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Khan Academy and the Art Story. • If a talk uses information from specific books, websites or articles these are referenced at the beginning of each talk and in the ‘References’ section of the relevant page. The talks that are based on an exhibition use the booklets and book associated with the exhibition. • Where possible images and information are taken from Wikipedia under 1 an Attribution-Share Alike Creative Commons License. • If I have forgotten to reference your work then please let me know and I will add a reference or delete the information. 1 ART HISTORY REVEALED 1. Impressionism in London 1. -

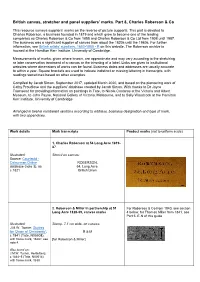

British Canvas, Stretcher and Panel Suppliers' Marks. Part 8, Charles

British canvas, stretcher and panel suppliers’ marks. Part 8, Charles Roberson & Co This resource surveys suppliers’ marks on the reverse of picture supports. This part is devoted to Charles Roberson, a business founded in 1819 and which grew to become one of the leading companies as Charles Roberson & Co from 1855 and Charles Roberson & Co Ltd from 1908 until 1987. The business was a significant supplier of canvas from about the 1820s until the 1980s. For further information, see British artists' suppliers, 1650-1950 - R on this website. The Roberson archive is housed at the Hamilton Kerr Institute, University of Cambridge. Measurements of marks, given where known, are approximate and may vary according to the stretching or later conservation treatment of a canvas or the trimming of a label. Links are given to institutional websites where dimensions of works can be found. Business dates and addresses are usually accurate to within a year. Square brackets are used to indicate indistinct or missing lettering in transcripts, with readings sometimes based on other examples. Compiled by Jacob Simon, September 2017, updated March 2020, and based on the pioneering work of Cathy Proudlove and the suppliers’ database created by Jacob Simon. With thanks to Dr Joyce Townsend for providing information on paintings in Tate, to Nicola Costaras at the Victoria and Albert Museum, to John Payne, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, and to Sally Woodcock at the Hamilton Kerr Institute, University of Cambridge. Arranged in twelve numbered sections according to address, business designation and type of mark, with two appendices. Work details Mark transcripts Product marks (not to uniform scale) 1. -

1 the Mind Is an Entity Full of Intricacies, Yet It Is Also An

1 The mind is an entity full of intricacies, yet it is also an individual’s ability to create anything and everything that may not exist within the confines of our physical world. Within our minds there lies an entirely new world. Within our minds there lies imagination. The imagination has transported avid thinkers and artists. During the Romantic Movement, the thoughts and emotions of an individual drove the art and literature, and the Victorian period that followed focused on capturing a romanticized scene of nineteenth century England. What was truly behind the Romantic and Victorian periods, and what is the story behind the paint on a canvas and pages of a book? What was the raw material that compelled these artists? Romanticism existed from approximately 1800 to 1840, philosophy and art working in tandem with literary exploration (Engell). Romanticism was “more than vague ‘inspiration’, the imagination became the way to grasp the truth” (Engell 4). Philosophers, people searching for the “purest means of expression” (Engell 139), sought this truth. The era of Romanticism emphasized the freedom of a creative mind and the subconscious, heightening the power of intellectual perception of the world we inhabit. Such notions were captured in an author’s musings, as well as dramatic imagery in visual works of art. “Imagination gives reason a language and the ability to appear in concrete forms” (Engell 48). Imagination is the creative force that extends one’s views on the world and offers the significance of invention (“Imagination”). Reason is the explanation of the mind’s quandaries, whereas imagination is the mind’s ability to utilize such explanation and form new ideas (“Reason”).